University District Market Analysis 6/18/07

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South University District-Sprague Corridor Planning Study Investment

0South University District-Sprague Corridor 1Investment Strategy 2Appendices UNIVERSITY DISTRICT—SPRAGUE CORRIDOR PLANNING STUDY EXISTING CONDITIONS ANALYSIS: DOCUMENT REVIEW UPDATE MEMO Submitted: February 8, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction............................................................................... 1 Key Findings .............................................................................. 2 Completed Plans and Studies........................................................ 3 Concurrent Projects, Plans and Studies ........................................ 13 UNIVERSITY DISTRICT – SPRAGUE CORRIDOR PLANNING STUDY INTRODUCTION The Document Review Memo provides a review of the plans, studies and projects that relate to the University District – Sprague Avenue Corridor (UDSC) Planning Study area, both completed and currently underway. Identifying key recommendations and policies in these documents will help ensure the creation of a workable, implementable plan that will guide the future development of the study area. This memo is an update to the Existing Conditions Analysis and provides an overview of recent and ongoing planning efforts and projects within and surrounding the study area. Along with this memo, the Existing Conditions Analysis includes a summary of Physical Characteristics and Sustainable Design and Development. This memo is organized as follows: Key Findings summarizes common themes and topics found in the review of existing plans and studies. Completed Plans and Studies includes a review of past and -

The Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer Atlas Preface Contents

The Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer Atlas Preface Contents The Spokane Valley-Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer Atlas presents a compre- Shaded Relief Map ...........................................Front Cover hensive summary of the region’s most precious groundwater resource and Using The is a basic reference of the geographic, geologic and hydrologic characteris- Preface and Contents........................... Inside Front Cover tics of this aquifer. Introduction ........................................................................ 1 Atlas The Atlas is designed in a narrative format supported by graphs, maps Aquifer from Space............................................................. 2 and images. It is intended for broad community use in education, plan- ning, and general technical information. The preparation and publica- Geography........................................................................... 3 tion of the atlas were partially funded by a United States Environmental Aquifer History................................................................... 4 Protection Agency aquifer wellhead protection grant. Climate and Population .................................................... 5 The information was collected and obtained from a variety of sources, If your interest in the Aquifer is including: United States Environmental Protection Agency, Idaho Depart- Geology................................................................................ 6 general, the authors suggest you page ment of Environmental Quality, Panhandle -

Spokane's University District: Appendices

APPENDIX A: SMART GROWTH IMPLEMENTATION ASSISTANCE VISIT Background on SGIA Communities around the country are interested in fostering economic growth, protecting environmental resources, and planning for development, but they may lack the tools, resources or information to achieve these goals. In response to this demand, the Development, Community, and Environment Division of the USEPA, launched the Smart Growth Implementation Assistance Program. This is a competitive program to provide technical assistance—through contractor services—to selected communities. This assistance is expected to improve the overall climate for infill, brownfields redevelopment, and the revitalization of non-brownfield sites—as well as deliver on other community and environmental goals. The City of Spokane was one of four communities selected to participate in the SGIA program in 2006. The city and its local partners asked EPA to help with the following tasks: • Develop an understanding of the Spokane market and potential for urban redevelopment in the University District; and • Identify strategies that the public and private sectors can use to create a strong neighborhood and increase development opportunities in the University District. After receiving this charge from the city, EPA worked with its contractor, ICF International, to assemble a team of national smart growth experts to assist the city. The Team visited Spokane January 17-19, 2007. Site visit activities included a two-day public design workshop, meetings with university and city leadership, and a final public presentation of the team’s findings. The workshop and presentation were open to the public and included a wide variety of participants including area residents, property owners, the business community, city and university leadership, local developers, and brokers. -

Visitor Map 2019–2020 Map Visitor Regional Official

Official Regional Visitor Map 2019–2020 Map Visitor Regional Official 49˚ North Deer Attractions (continued) Spokane Regional Map Legend Mountain Resort Lake I Silverwood Theme Park I Timberline Adventures Mt. Spokane Ski The Northwest’s largest theme and World-class, canopy style, zip-line & Snowboard Park Accommodations Golf Course Camping & RV Resort Mt. Spokane water park. silverwoodthemepark. tours. The ultimate outdoor experience. com, 208.683.3400, 27843 N Hwy 95, ziptimberline.com, 208.820.2080, 210 Athol, ID Sherman Ave #1, Coeur d’Alene, ID Regional Attraction Regional Accommodations 1C Spokane Tribe Casino Mt. Spokane Trails “Every time I visit Spokane, Events you don’t want to miss 24-hour gaming excitement. Get a Sun Hiking & Biking Trail Centennial Trail visitspokane.com Club Card today. spokanetribecasino.com, 1.888.SPOKANE I find something new.” 877.786.9467, 14300 W State Route 2 Mountain Resort Downtown Detail (reverse) 2 Hwy, Airway Heights, WA more, any night of the week the of night any more, — 1889 Magazine Live music, dancing, theater and and theater dancing, music, Live Water Exploration A Inlander Restaurant Week Spokane County Entertainment Dragon Creek State Park City of Spokane Valley Last Week of February Interstate Fair to local boutiques local to It’s the most delicious time of the year. February means one thing in Everything from big-name retailers retailers big-name from Everything B3 Baymont Inn & Suites B4 My Place Hotel Second Weekend in September Shops Enjoy free WiFi and breakfast. Indoor Economy, extended-stay hotel Spokane — Inlander Restaurant Week. From February 21 – March 2, Golf An annual event that marks the beginning of fall, the Spokane Wild Rose RV Park pool and spa. -

Directions to Convention Center Parking

DIRECTIONS TO CONVENTION CENTER PARKING SOUTHBOUND TRAFFIC FROM HIGHWAY 2 & 395 (DIVISION ST.) FOLLOW DIVISION ST. TOWARD DOWNTOWN SPOKANE. STAY IN THE FAR RIGHT LANE AS YOU CROSS THE BRIDGE, DIVISION ST. TURNS INTO ONTO SPOKANE FALLS BLVD. AFTER THE LIGHT, TURN RIGHT ONTO SPOKANE FALLS COURT TO ACCESS THE CONVENTION CENTER PARKING GARAGE. SPOKANE ARENA PARKING CITY TICKET PARK & RIDE DEAN CALISPEL ATLANTIC NORMANDIE RUBY HOWARD STREET HOWARD DIVISION STREET CATALDO CATALDO TURN AROUND AT CATALDO MALLON AVE. RUBY NORTH RIVER DRIVE PARKING LEGEND PUBLIC PARKING FACILITY WASHINGTON STREET SPOKANE RIVER DIVISION STREET PUBLIC PARKING FACILITY RIVERFRONT PARK accepting EasyPark validation TUNNEL DIVISION STREET SPOKANE CONVENTION CENTER PARKING GARAGE RESTAURANT GROUP HEALTH HOTEL EXHIBIT HALLS PARKING GARAGE INB PERFORMING CONVENTION ARTS CENTER CENTER TRENT AVE WEST SPOKANE FALLS BOULEVARD WEST SPOKANE FALLS BOULEVARD STEVENS STREET BROWNE STREET BROWNE HOWARD STREET HOWARD BERNARD STREET DIVISION STREET WASHINGTON STREET MAIN AVENUE MAIN AVENUE RIVERSIDE AVENUE RIVERSIDE AVENUE GONZAGA RUBY UNIVERSITY SPOKANE CONVENTION CENTER DIRECTIONS MAPLE ST WASHINGTON ST WASHINGTON LINCOLN ST LINCOLN N DIVISION ST MONROE ST N HAMILTON ST N HAMILTON From I-90 take Division St. (Newport/Colville) Exit 281. Off ramp E TRENT AVE turns into northbound Division St. Continue north to Spokane Falls Boulevard, turn left onto Spokane Falls Boulevard. Just W SPOKANE FALLS BLVD after the next light, turn right onto Spokane Falls Court. The EXIT 281 parking garage is under the Exhibit Halls. DIVISION ST. MAPLE WALNUT 3RD AVE NEWPORT COLLVILLE EXIT 282 EXIT 280 334 WEST SPOKANE FALLS BOULEVARD SPOKANE WASHINGTON 99201 P 509.279.7000 F 509.279.7060 SPOKANECENTER.COM. -

The Off-Peak Ticket Incentive Demonstration in Spokane, WA

1 U M T A-W A-06-00 1 8-85- 1 : i— 1 8.5 . A3 7 no. DOT- T SC- LJ MTA- The Off-Peak Ticket Incentive 35- I 2 U.S. Department Demonstration in Spokane, WA of Transportation Urban Mass Transportation UMTA/TSC Evaluation Series Final Report Administration May 1985 UMTA Technical Assistance Program NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Govern- ment assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse pro- ducts or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are con- sidered essential to the object of this report. 1 2 if t It S' -S" i A 37 no. DO/' Technical Report Documentation Page fTSC- \t M Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient' > Cotalog No. sS /X UMTA-WA-06-0018-85- 4. Title and Subtitle / 5. Report Date -_May 1985 THE OFF-PEAK TICKET INCENTIVE DEMONSTR^^-^^^r^ 6./ Performing Organization Code IN SPOKANE, IJA / ^T/0a , DTS-64 N j Sfp. ,' 8. Performing Organization Report No. / 0U 7. Author's) ISSS Sydwell Flynn / D0T-TSC--UMTA-85-1 ( 9. Performing Organization Nome and Address ‘s*RY 1 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) UM527/R5631 Crain & Associates, Inc.* 11. Contract or Gront No. 343 Second Street, Suite A D0T-TSC- 1755 Los Altos, CA 94022 13. Type of Report and Period Covered • 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Final Report U.S. Department of Transportation August 1980 - July 1984 Urban Mass Transportation Administration Office of Management Research and Transit Services 14. -

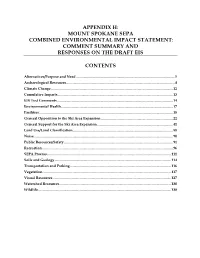

Mount Spokane Sepa Combined Environmental Impact Statement: Comment Summary and Responses on the Draft Eis

APPENDIX H: MOUNT SPOKANE SEPA COMBINED ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT: COMMENT SUMMARY AND RESPONSES ON THE DRAFT EIS CONTENTS Alternatives/Purpose and Need ............................................................................................................. 1 Archaeological Resources ........................................................................................................................ 4 Climate Change ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Cumulative Impacts ................................................................................................................................ 13 EIS Text Comments ................................................................................................................................ 14 Environmental Health ............................................................................................................................ 17 Facilities .................................................................................................................................................... 18 General Opposition to the Ski Area Expansion ................................................................................ 22 General Support for the Ski Area Expansion .................................................................................... 41 Land Use/Land Classification .............................................................................................................. -

Central Downtown

CENTRAL DOWNTOWN S. Maple Street to S. Lincoln Street Mallon 3 Post N Central Spokane 2 Monroe Lincoln Riverfront Park 1 4 6 Spokane Falls Blvd. 5 7 Central Downtown, the heart of downtown Spokane. After the 1889 fire, in which much of downtown Spokane was destroyed, 8 Stevens a number of architects relocated here and made names for Main themselves by designing enduring buildings of the then 9 current, and now remarkable, styles of the day. These include Wall the Arts and Crafts bungalows, Queen Anne houses, Tudoresque Post Howard mansions, Romanesque churches, and Gothic commercial Lincoln 18 buildings, as well as Classic Revival office buildings and Art Riverside Deco theaters. The years between the fire and World War II 10 were rich in regards to the development of a vibrant downtown 12 11 and a city of national renown. As early as 1905, President Sprague Theodore Roosevelt was quoted as saying in the Chamber of 13 17 Commerce publication, Spokane: A Modern City, “I never saw Washington two such cities anywhere as Spokane and Seattle. If my eldest First First boy was large enough to be choosing a place, I would advise 14 16 him to locate in one or the other of those cities and it is a shake-up between them.” 15 Second 1 CLOCK TOWER (NR) Riverfront Park 4 MONTGOMERY WARDS (City Hall) The clock tower is all that remains of the Great Northern Train Station which (NR & SR) 808 W. Spokane Falls Boulevard was demolished in the early 1970s in preparation for Expo ‘74. -

Spokane City Drive

SPOKANE CITY DRIVE VisitSpokane.com 1.888.SPOKANE Riverfront Park 507 N Howard Street (47°39’37.20”N, 117°25’15.93”W) One-hundred acres of beautifully manicured lawns and trees, interesting art and amazing attractions located in the heart of downtown Spokane. The INB Performing Arts Center, Spokane Convention Center (located on Spokane Falls Blvd, the south boundary of the park) and the park itself are the legacy of Spokane’s Expo ’74 World’s Fair. Plenty of parking is located along the south side of Spokane Falls Boulevard. Turn right (north) on to Post St. (City Hall will now be on your left) to Mallon Ave. Turn right on to Mallon Ave and proceed to… 1 The Flour Mill 621 W Mallon Avenue (47°39’54.33”N, 117°25’18.92”W) Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Flour Mill was originally built over a hundred years ago to harness the energy of the Spokane River to grind wheat into flour. It was renovated during the excitement prior to the Expo ’74 World’s Fair into an eclectic collection of specialty shops, eateries and office space. On the north side across the street you will see the… 2 Spokane Veterans Memorial Arena 720 W Mallon Avenue (47°39’55.60”N, 117°25’20.65”W) The Spokane Arena is a 12,500-seat, state-of-the art, multi-purpose venue. The Arena has hosted a variety of events and concerts, numerous Men’s and Women’s NCAA Basketball Tournaments and the record-breaking 2007 and 2010 US Figure Skating Championships. -

Step Out: Walking & Hiking in Spokane County

Step Out: Walking & Hiking in Spokane County Parking Restrooms Playground Route type: Dirt Trail Route type: Sidewalks Route type: Grass, dirt, sidewalks Distance: 3.5 miles (there and back) Distance: 1.4 miles Distance: 0.8 miles Little Spokane River Indian Painted Rocks Steps: 7,000 Steps: 2,800 Steps: 1,620 ~ TED TED TED This is a nice, easy-paced hike alongside a marsh environment. Located 6 miles northwest of downtown Spokane, Time: 1 hour Cheney ~ EWU Time: 24 minutes Holmberg Park Time: 14 minutes TIMA TIMA TIMA S S S this hike has some of the most beautiful scenery in our area. At the trailhead, you will find ancient Indian paintings E Calories burned: 294 E Calories burned: 118 E Calories burned: 67 on the rocks; and as you make your way along the riverbanks, you will want to keep an eye out for the blue heron rookery in the tall cottonwoods by the river. There are a variety of animals that make the Little Spokane their home, including beaver, coyotes, deer, cougar and even moose. (No bikes or pets.) on St. t Safety Tips ashing 65,66 W Elm Westover RIVERSIDE Indian STATE PARK Painted wAlways use crosswalks. Hun Rocks ting wChoose well lit areas if out after dark. t wTake a cell phone or a whistle. on W ay 291 w wTry to walk with a buddy; this can also aikiki Rd. fountain 5th St. e High make it more fun. er w ane Riv Be aware of any hazardous conditions. EASTERN WA orth Driv Little Spok Consider walking sticks and repellent. -

Restaurants Convenient to Spokane Convention Center

Restaurants Convenient to Spokane Convention Center MacKenzie River Pizza, Grill & Pub - Downtown 818 W. Riverside Ave. Spokane, WA 99201 Phone: (509) 315-4447 Website: www.mackenzieriverpizza.com Description: Featuring an incredible array of delectable dishes, always flavorful, fresh and served up in heaping portions. The acclaimed gourmet pizzas are offered on a variety of crusts with toppings from classic pepperoni to pesto, ricotta and sun-dried tomato. We also offer hearty sandwiches served warm on fresh baked bread, Montana-sized salads, pastas that will wow your taste buds and home-style entrees to satisfy your cravings. The Melting Pot of Spokane 707 W Main Ave, Crescent Building, Skywalk Level Spokane, WA 99201 Phone: (509) 926-8000 Website: www.meltingpot.com/spokane/welcome Description: At the Melting Pot, fondue truly becomes a memorable four course dining experience where patrons can dip into something different and discover all the ingredients for the perfect night out including a relaxed atmosphere, private tables, attentive service, fine wines, private banquet room and great memories. Reservations are recommended. Nordstrom Cafe River Park Square, 3rd Level, 828 W Main, River Park Square Spokane, WA 99201 Phone: (509) 455-6111 Website: www.nordstrom.com Description: Yummy paninis, soups, salads and desserts! The Onion Bar & Grill 302 W Riverside Ave Spokane, WA 99201 Phone: (509) 747-3852 Website: www.theonion.biz Description: Fun, fast and friendly. Serving pasta, fajitas, chicken platters, gourmet salads, and a wide variety of hamburgers. Lots of imported & domestic draft beers and cocktails. We love kids! Can accommodate groups of 10 or more. Has private dining area. -

Spokane Regional Health District Food Inspection Violations 7/1/2019

Spokane Regional Health District Spokane Regional Health District 1101 W College Ave, Room 402 Spokane, WA 99201 Food Inspection Violations Phone: (509) 324-1560 ext 1 10/1/2019 to 9/1/2021 Facility Address 180 Bar & Bistro 180 S Howard ST Inspection Date: 06/15/2020 PRE OPERATIONAL Violations Inspection Date: 11/13/2020 ROUTINE INSPECTION Violations 07 Food obtained from approved source 26 Compliance with risk control plan, variance, plan of operation; valid permit; approved procedures f Inspection Date: 04/26/2021 ROUTINE INSPECTION Violations Inspection Date: 08/20/2021 ROUTINE INSPECTION Violations 02 Food worker cards current for all food workers; new food workers trained 06 Adequate handwashing facilities 25 Toxic substances properly identified, stored, used 34 Wiping cloths properly used, stored; proper sanitizer 1st Ave Coffee 1011 W 1st AVE Inspection Date: 12/21/2020 ROUTINE INSPECTION Violations 2ND BASE ESPRESSO 3001 E SANSON AVE Inspection Date: 10/10/2019 ROUTINE INSPECTION Violations 33 Potential food contamination prevented during delivery, preparation, storage, display 34 Wiping cloths properly used, stored; proper sanitizer 45 Sewage, wastewater properly disposed Inspection Date: 08/19/2021 ROUTINE INSPECTION Violations 3 Ninjas Curbside and Catering 1198 W Summit PKY Inspection Date: 02/04/2020 ROUTINE INSPECTION Violations Inspection Date: 01/12/2021 ROUTINE INSPECTION Violations Inspection Date: 07/13/2021 ROUTINE INSPECTION Violations 3RD AVE GROCERY MART 702 W 3RD AVE Inspection Date: 10/03/2019 ROUTINE INSPECTION Violations Report Date: 9/9/2021 Facility Address 5 NORTH BREWING COMPANY 6501 N CEDAR RD 1 Inspection Date: 10/22/2019 1ST RE-INSPECTION Violations Inspection Date: 03/12/2020 ROUTINE INSPECTION Violations 21 Proper cold holding temperatures (5pts.