Management of Cannabis Use Disorder and Related Issues a Clinician's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis: Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning

6 Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning Robert Gabrys, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Amy Porath, Ph.D., Director, Research, CCSA Key Points • Regular use refers to weekly or more frequent cannabis use over a period of months to years. Regular cannabis use is associated with mild cognitive difficulties, which are typically not apparent following about one month of abstinence. Heavy (daily) and long-term cannabis use is related to more This is the first in a series of reports noticeable cognitive impairment. that reviews the effects of cannabis • Cannabis use beginning prior to the age of 16 or 17 is one of the strongest use on various aspects of human predictors of cognitive impairment. However, it is unclear which comes functioning and development. This first — whether cognitive impairment leads to early onset cannabis use or report on the effects of chronic whether beginning cannabis use early in life causes a progressive decline in cannabis use on cognitive functioning cognitive abilities. provides an update of a previous report • Regular cannabis use is associated with altered brain structure and function. with new research findings that validate Once again, it is currently unclear whether chronic cannabis exposure and extend our current understanding directly leads to brain changes or whether differences in brain structure of this issue. Other reports in this precede the onset of chronic cannabis use. series address the link between chronic • Individuals with reduced executive function and maladaptive (risky and cannabis use and mental health, the impulsive) decision making are more likely to develop problematic cannabis use and cannabis use disorder. -

Alloimmunization in Pregnancy

Maternal Cannabis Use in Pregnancy and LactationAlloimmunization in Jamie Lo MD MCR, Assistant Professor MaternalJamiePregnancy FetalLo MD Medicine Oregon Health & Science University DecemberDATE: September 18, 2020 23, 2016 Disclosures • I have no relevant financial relationships to disclose or conflicts of interest to resolve Manzanita, Oregon Marijuana Legalization Trend • Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug in pregnancy • 33 states and Washington DC have legalized medical marijuana • 11 states and Washington DC have legalized recreational marijuana • To address the opioid crisis, 3 states have passed laws to allow marijuana to be prescribed in place of opioids References: www.timesunion.com/technology/businessinsider/article/This-map-shows-every-state-that-has-legalized-12519184.php, Accessed October 10, 2020 Understanding the Impact of Legalization Reference: NW HIDTA Report What is marijuana? • Cannabis sativa plant • Contains over 600 chemicals – Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC): main psychoactive component • Small and highly lipophilic • Rapidly distributed to the brain and fat • Metabolized by the liver • Half-life is 20-36hrs to 4-6 days • Detectable up to 30 days after using – Cannabidiol (CBD): second most prevalent main active ingredient Endocannabinoid System References: Nahtigal et al. J Pain Manage. 2016 Cannabidiol vs. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol • CB1 receptor (found on neurons and glial cells in the brain) – Binding of THC results in euphoric effects – CBD has 100 fold less affinity to CB1 receptor than -

Impact of Recreational and Medical Marijuana Use During Pregnancy and Lactation on the Newborn

If it’s Legal it Can’t be all Bad… can it? Impact of Recreational and Medical Marijuana use during Pregnancy and Lactation on the Newborn Moni Snell MSN RN NNP-BC Neonatal Nurse Practitioner NICU Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region Objectives Understand the current use, risks and differences between medical (CBD) and recreational (THC) marijuana Discuss evidence based education for women and current management strategies for caring for newborns exposed to THC through pregnancy and breastfeeding Discuss the impact of increased newborn exposure to recreational and medical marijuana with it’s legalization Marijuana… common term for Recreational Cannabis in the form of dried leaves, stems or seeds Anticipated legalization in Canada July 2018 Currently legal in 29 states in the US Recreational use and self –medication with cannabis is very common • Cannabis: pot, grass, reefer, weed, herb, Mary Jane, or MJ Peak use is in the 20’s and 30’s : women’s • Contains over 700 chemicals, about 70 of reproductive years which are cannabinoids • Hash and hash oil also come from the cannabis plant Cannabis Ingredients Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical that makes people high Cannabidiol (CBD) is known for its medicinal qualities for pain, inflammation, and anxiety o CBD does not make you feel as high Different types of cannabis and effects depend on the amount of THC or CBD, other chemicals and their interactions THC content is known to have increased over the past several decades Oils have higher percentage of THC and THC in edible cannabis products can vary widely and can be potent THC content/potency of THC confiscated by DEA in US has been steadily increasing Consequences could be worse than in the past, especially among new users or in young people with developing brains ElSohly et al, (2016) Changes in cannabis potency over the last 2 decades (1995-2014): Analysis of current data in the United States. -

Maternal Use of Cannabis and Pregnancy Outcome

BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology January 2002, Vol. 109, pp. 21–27 Maternal use of cannabis and pregnancy outcome David M. Fergussona, L. John Horwooda, Kate Northstoneb,*, ALSPAC Study Teamb Objective To document the prevalence of cannabis use in a large sample of British women studied during pregnancy, to determine the association between cannabis use and social and lifestyle factors and assess any independent effects on pregnancy outcome. Design Self-completed questionnaire on use of cannabis before and during pregnancy. Sample Over 12,000 women expecting singletons at 18 to 20 weeks of gestation who were enrolled in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. Methods Any association with the use of cannabis before and during pregnancy with pregnancy outcome was examined, taking into account potentially confounding factors including maternal social background and other substance use during pregnancy. Main outcome measures Late fetal and perinatal death, special care admission of the newborn infant, birthweight, birth length and head circumference. Results Five percent of mothers reported smoking cannabis before and/or during pregnancy; they were younger, of lower parity, better educated and more likely to use alcohol, cigarettes, coffee, tea and hard drugs. Cannabis use during pregnancy was unrelated to risk of perinatal death or need for special care, but, the babies of women who used cannabis at least once per week before and throughout pregnancy were 216g lighter than those of non-users, had significantly shorter birth lengths and smaller head circumferences. After adjustment for confounding factors, the association between cannabis use and birthweight failed to be statistically significant ( P ¼ 0.056 ) and was clearly non-linear: the adjusted mean birthweights for babies of women using cannabis at least once per week before and throughout pregnancy were 90g lighter than the offspring of other women. -

Is Cannabis Addictive?

Is cannabis addictive? CANNABIS EVIDENCE BRIEF BRIEFS AVAILABLE IN THIS SERIES: ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for youth aged 13–17 years. ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for young adults aged 18–25 years. ` Does cannabis use increase the risk of developing psychosis or schizophrenia? ` Is cannabis safe during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding? ` Is cannabis addictive? PURPOSE: This document provides key messages and information about addiction to cannabis in adults as well as youth between 16 and 18 years old. It is intended to provide source material for public education and awareness activities undertaken by medical and public health professionals, parents, educators and other adult influencers. Information and key messages can be re-purposed as appropriate into materials, including videos, brochures, etc. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2018 Publication date: August 2018 This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, provided that it is reproduced for public education purposes and that due diligence is exercised to ensure accuracy of the materials reproduced. Cat.: H14-264/3-2018E-PDF ISBN: 978-0-660-27409-6 Pub.: 180232 Key messages ` Cannabis is addictive, though not everyone who uses it will develop an addiction.1, 2 ` If you use cannabis regularly (daily or almost daily) and over a long time (several months or years), you may find that you want to use it all the time (craving) and become unable to stop on your own.3, 4 ` Stopping cannabis use after prolonged use can produce cannabis withdrawal symptoms.5 ` Know that there are ways to change this and people who can help you. -

Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: a Case Report in Mexico

CASE REPORT Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report in Mexico Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz,1 Rodrigo Marín-Navarrete,3 Emmanuel Solís Ayala,1 Ana de la Fuente-Martín2 1 Medicina Interna, Hospital Ánge- ABSTRACT les Pedregal. 2 Escuela de Medicina, Universi- Background. The first case report on the Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was registered in 2004. dad la Salle. Years later, other research groups complemented the description of CHS, adding that it was associated with 3 Unidad de Ensayos Clínicos, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría such behaviors as chronic cannabis abuse, acute episodes of nausea, intractable vomiting, abdominal pain Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. and compulsive hot baths, which ceased when cannabis use was stopped. Objective. To provide a brief re- view of CHS and report the first documented case of CHS in Mexico. Method. Through a systematic search Correspondence: Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz. in PUBMED from 2004 to 2016, a brief review of CHS was integrated. For the second objective, CARE clinical Medicina Interna, Hospital Ángeles case reporting guidelines were used to register and manage a patient with CHS at a high specialty general del Pedregal. hospital. Results. Until December 2016, a total of 89 cases had been reported worldwide, although none from Av. Periférico Sur 7700, Int. 681, Latin American countries. Discussion and conclusion. Despite the cases reported in the scientific literature, Col. Héroes de Padierna, Del. Magdalena Contreras, C.P. 10700 experts have yet to achieve a comprehensive consensus on CHS etiology, diagnosis and treatment. The lack Ciudad de México. of a comprehensive, standardized CHS algorithm increases the likelihood of malpractice, in addition to con- Phone: +52 (55) 2098-5988. -

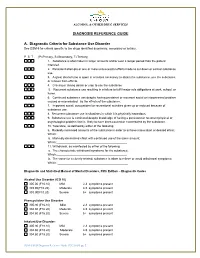

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis: Regular Use and Mental Health

1 Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis Regular Use and Mental Health Sarah Konefal, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Robert Gabrys, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Amy Porath, Ph.D., Director, Research, CCSA Key Points • Regular cannabis use refers to weekly or more frequent cannabis use over a period of months to years. • Regular cannabis use is at least twice as common among individuals with This is the first in a series of reports mental disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, depressive and that reviews the effects of cannabis anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). use on various aspects of human • There is strong evidence linking chronic cannabis use to increased risk of developing psychosis and schizophrenia among individuals with a family functioning and development. This history of these conditions. report on the effects of regular • Although smaller, there is still a risk of developing psychosis and cannabis use on mental health provides schizophrenia with regular cannabis use among individuals without a family an update of a previous report with history of these disorders. Other factors contributing to increased risk of new research findings that validate and developing psychosis and schizophrenia are early initiation of use, heavy or extend our current understanding of daily use and the use of products high in THC content. this issue. Other reports in this series • The risk of developing a first depressive episode among individuals who use address the link between regular cannabis regularly is small after accounting for the use of other substances cannabis use and cognitive functioning, and common sociodemographic factors. -

Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use

The Corinthian Volume 20 Article 16 November 2020 Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use Celia G. Imhoff Georgia College and State University Follow this and additional works at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Imhoff, Celia G. (2020) "Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use," The Corinthian: Vol. 20 , Article 16. Available at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian/vol20/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Knowledge Box. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Corinthian by an authorized editor of Knowledge Box. LONG-TERM OUTCOMES OF CHRONIC, RECREATIONAL MARIJUANA USE Amidst insistent, nationwide demand for the acceptance of recreational marijuana, many Americans champion the supposedly non-addictive, inconsequential, and creativity-inducing nature of this “casual” substance. However, these personal beliefs lack scientific evidence. In fact, research finds that chronic adolescent and young adult marijuana use predicts a wide range of adverse occupational, educational, social, and health outcomes. Cannabis use disorder is now recognized as a legitimate condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and cannabis dependence is gaining respect as an authentic drug disorder. Some research indicates that medical marijuana can be somewhat effective in treating assorted medical conditions such as appetite in HIV/AIDS patients, neuropathic pain, spasticity and multiple sclerosis, nausea, and seizures, and thus its value to medicine continues to evolve (Atkinson, 2016). However, many studies on medical marijuana produce mixed results, casting doubt on our understanding of marijuana's medicinal properties (Atkinson, 2016; Keehbauch, 2015). -

Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome: an Update on the Pathophysiology and Management

REVIEW ARTICLE Annals of Gastroenterology (2020) 33, 571-578 Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome: an update on the pathophysiology and management Abhilash Perisettia, Mahesh Gajendranb, Chandra Shekhar Dasaric, Pardeep Bansald, Muhammad Azize, Sumant Inamdarf, Benjamin Tharianf, Hemant Goyalg University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR; Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso; Kansas City VA Medical Center; Moses Taylor Hospital and Reginal Hospital of Scranton, Scranton, PA; University of Toledo, HO; The Wright Center for Graduate Medical Education, Scranton, PA, USA Abstract Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is a form of functional gut-brain axis disorder characterized by bouts of episodic nausea and vomiting worsened by cannabis intake. It is considered as a variant of cyclical vomiting syndrome seen in cannabis users especially characterized by compulsive hot bathing/showers to relieve the symptoms. CHS was reported for the first time in 2004, and since then, an increasing number of cases have been reported. With cannabis use increasing throughout the world as the threshold for legalization becomes lower, its user numbers are expected to rise over time. Despite this trend, a strict criterion for the diagnosis of CHS is lacking. Early recognition of CHS is essential to prevent complications related to severe volume depletion. The recent body of research recognizes that patients with CHS impose a burden on the healthcare systems. Understanding the pathophysiology of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) remains central in explaining the clinical features and potential drug targets for the treatment of CHS. The frequency and prevalence of CHS change in accordance with the doses of tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids in various formulations of cannabis. -

Cannabis & Human Milk

CANNABIS & HUMAN MILK Two recent studies about cannabis use while breaseeding, both done with Colorado connecons, may have implicaons for your paents. With marijuana use during pregnancy and lactaon on the rise due to legalizaon in more states, these researchers are filling a gap in knowledge about this important health topic. The first study, conducted by Thomas Hale PhD and colleagues, looked at the transfer of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) into human milk aer maternal inhalaon of a prescribed amount of cannabis. Eight anonymous women from Colorado enrolled in the study and were instructed to disconnue any cannabis use for 24 hours, provide a sample of their milk, then smoke the prescribed amount of cannabis and collect milk at 20 minutes, one, two and four hours. The results showed that THC was transferred into milk at 2.5% of the maternal dose. The second study, done by researchers at the University of Colorado (CU) School of Public Health, used Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data from 2014 and 2015. In this group, 5.7% reported using marijuana during pregnancy and 5% during breaseeding. They discovered that prenatal marijuana use was associated with a 50% increased chance of low birth weight in babies regardless of tobacco use. Prenatal marijuana use was four mes higher among women who were younger, less educated, received Medicaid or WIC, were white, unmarried and lived in poverty. The study suggests that prenatal cannabis use has a detrimental impact on a baby's brain funcon starng in toddlerhood, specifically issues related to aenon deficit disorder. 88% of women who use cannabis in pregnancy also breaseed their babies. -

Pregnant People's Perspectives on Cannabis Use During

Pregnant people's perspectives on cannabis use during pregnancy: A systematic review and integrative mixed-methods research synthesis Meredith Vanstone1, Janelle Panday1, Anuoluwa Popoola1, Shipra Taneja1, Devon Greyson2, Sarah McDonald1, Rachael Pack3, Morgan Black1, Beth Davis1, and Elizabeth Darling1 1McMaster University 2University of Massachusetts Amherst 3Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry March 17, 2021 Abstract Background: Cannabis use during the perinatal period is rising. Objectives: To synthesize existing knowledge on the per- spectives of pregnant people and their partners about cannabis use in pregnancy and lactation. Search strategy: We searched MEDLINE, APA PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Social Science Citation Index, Social Work Abstracts, ProQuest Sociology Collection up until April 1, 2020. Selection criteria: Eligible studies were those of any methodology which included the perspectives and experiences of pregnant or lactating people and their partners on cannabis use during pregnancy or lactation, with no time or geographical limit. Data collection and analysis: We employed a convergent integrative approach to the analysis of findings from all studies, using Sandelowski's technique of \qualitizing statements" to extract and summarize relevant findings from inductive analysis. Main results: We identified 23 studies of pregnant people's views about cannabis use in pregnancy. Comparative analysis revealed that whether cannabis was studied alone or grouped with other substances resulted in significant diversity in descriptions of participant decision-making priorities and perceptions of risks and benefits. Studies combining cannabis with other substance seldom addressed perceived benefits or reasons for using cannabis. Conclusions: The way cannabis is grouped with other substances influences the design and results of research.