Small-Scale Mining and Alluvial Gold Panning Within the Zambezi Basin : an Ecological Time Bomb and Tinderbox for Future Conflicts Among Riparian States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozambique Zambia South Africa Zimbabwe Tanzania

UNITED NATIONS MOZAMBIQUE Geospatial 30°E 35°E 40°E L a k UNITED REPUBLIC OF 10°S e 10°S Chinsali M a l a w TANZANIA Palma i Mocimboa da Praia R ovuma Mueda ^! Lua Mecula pu la ZAMBIA L a Quissanga k e NIASSA N Metangula y CABO DELGADO a Chiconono DEM. REP. OF s a Ancuabe Pemba THE CONGO Lichinga Montepuez Marrupa Chipata MALAWI Maúa Lilongwe Namuno Namapa a ^! gw n Mandimba Memba a io u Vila úr L L Mecubúri Nacala Kabwe Gamito Cuamba Vila Ribáué MecontaMonapo Mossuril Fingoè FurancungoCoutinho ^! Nampula 15°S Vila ^! 15°S Lago de NAMPULA TETE Junqueiro ^! Lusaka ZumboCahora Bassa Murrupula Mogincual K Nametil o afu ezi Namarrói Erego e b Mágoè Tete GiléL am i Z Moatize Milange g Angoche Lugela o Z n l a h m a bez e i ZAMBEZIA Vila n azoe Changara da Moma n M a Lake Chemba Morrumbala Maganja Bindura Guro h Kariba Pebane C Namacurra e Chinhoyi Harare Vila Quelimane u ^! Fontes iq Marondera Mopeia Marromeu b am Inhaminga Velha oz P M úngu Chinde Be ni n è SOFALA t of ManicaChimoio o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o gh ZIMBABWE o Bi Mutare Sussundenga Dondo Gweru Masvingo Beira I NDI A N Bulawayo Chibabava 20°S 20°S Espungabera Nova OCE A N Mambone Gwanda MANICA e Sav Inhassôro Vilanculos Chicualacuala Mabote Mapai INHAMBANE Lim Massinga p o p GAZA o Morrumbene Homoíne Massingir Panda ^! National capital SOUTH Inhambane Administrative capital Polokwane Guijá Inharrime Town, village o Chibuto Major airport Magude MaciaManjacazeQuissico International boundary AFRICA Administrative boundary MAPUTO Xai-Xai 25°S Nelspruit Main road 25°S Moamba Manhiça Railway Pretoria MatolaMaputo ^! ^! 0 100 200km Mbabane^!Namaacha Boane 0 50 100mi !\ Bela Johannesburg Lobamba Vista ESWATINI Map No. -

Water Scenarios for the Zambezi River Basin, 2000 - 2050

Water Scenarios for the Zambezi River Basin, 2000 - 2050 Lucas Beck ∗ Thomas Bernauer ∗∗ June 1, 2010 Abstract Consumptive water use in the Zambezi river basin (ZRB), one of the largest fresh- water catchments in Africa and worldwide, is currently around 15-20% of total runoff. This suggests many development possibilities, particularly for irrigated agriculture and hydropower production. Development plans of the riparian countries indicate that con- sumptive water use might increase up to 40% of total runoff already by 2025. We have constructed a rainfall–runoff model for the ZRB that is calibrated on the best available runoff data for the basin. We then feed a wide range of water demand drivers as well as climate change predictions into the model and assess their implications for runoff at key points in the water catchment. The results show that, in the absence of effective international cooperation on water allocation issues, population and economic growth, expansion of irrigated agriculture, and water transfers, combined with climatic changes are likely to have very important transboundary impacts. In particular, such impacts involve drastically reduced runoff in the dry season and changing shares of ZRB coun- tries in runoff and water demand. These results imply that allocation rules should be set up within the next few years before serious international conflicts over sharing the Zambezi’s waters arise. Keywords: Water demand scenarios, Zambezi River Basin, water institutions ∗[email protected] and [email protected], ETH Zurich, Center for Comparative and Interna- tional Studies and Center for Environmental Decisions, Weinbergstrasse 11, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland, Phone: +41 44 632 6466 ∗∗We are very grateful to Tobias Siegfried, Wolfgang Kinzelbach, and Amaury Tilmant for highly useful comments on previous versions of this paper. -

Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin This Book Is a Product of the CODESRIA Comparative Research Network

Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin This book is a product of the CODESRIA Comparative Research Network. Ecological Changes in the Zambezi River Basin Edited by Mzime Ndebele-Murisa Ismael Aaron Kimirei Chipo Plaxedes Mubaya Taurai Bere Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa DAKAR © CODESRIA 2020 Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop, Angle Canal IV BP 3304 Dakar, 18524, Senegal Website: www.codesria.org ISBN: 978-2-86978-713-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission from CODESRIA. Typesetting: CODESRIA Graphics and Cover Design: Masumbuko Semba Distributed in Africa by CODESRIA Distributed elsewhere by African Books Collective, Oxford, UK Website: www.africanbookscollective.com The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) is an independent organisation whose principal objectives are to facilitate research, promote research-based publishing and create multiple forums for critical thinking and exchange of views among African researchers. All these are aimed at reducing the fragmentation of research in the continent through the creation of thematic research networks that cut across linguistic and regional boundaries. CODESRIA publishes Africa Development, the longest standing Africa based social science journal; Afrika Zamani, a journal of history; the African Sociological Review; Africa Review of Books and the Journal of Higher Education in Africa. The Council also co- publishes Identity, Culture and Politics: An Afro-Asian Dialogue; and the Afro-Arab Selections for Social Sciences. -

Letter of Concern: Mining in the Lower Zambezi River Water Catchment and Protected Areas

Letter of Concern: Mining in the Lower Zambezi River Water Catchment and Protected Areas INTRODUCTION This petition is submitted to express the growing concern by the traditional residents of the Lower Zambezi Valley, the international conservation community, and local leaseholders in regard to the numerous proposed mining projects currently under development in the area. These projects are likely to impact the area’s irreplaceable eco-system and cause irreversible damage to one of the greatest natural heritage areas in Zambia, and all of Africa. The mining projects are located both within and adjacent to the Lower Zambezi National Park, the recently formed Partnership Park (the first of its kind in Zambia which is a partnership between community and GMA leaseholders), and Mana Pools National Park, a World Heritage Site located directly across the river in neighboring Zimbabwe. The area currently supports many communities in which thousands of local people depend on sustainable industries including agriculture, fisheries and tourism. As per the signatories document attached, you will see many of the communities are represented here. All of these communities and sustainable enterprises are under threat by the potential consequences of the proposed mining, which does not provide long-term economic benefits to Zambian citizens. As a unique and world-renowned ecosystem with immense financial and ecological value to Zambia, this area deserves the highest level of protection. We are very concerned about the profound and long- lasting negative socio-economic and environmental impacts that are likely to occur if the proposed mining operations go forward. The proposed open pit mining projects are located inside the Zambezi River water catchment, in close proximity to tributaries to this invaluable water resource. -

The Pungwe, Buzi, and Save (Pubusa)

The Pungwe, Buzi and Save (Pubusa) and Central Zambezi Basins Portfolio Jefter Sakupwanya, Mbali Malekane; June 2014 General Overview of the Basins The current reality in the Basins is one of increasing populations despite the impacts of the HIV/AIDS endemic 1.6 million people in the Pungwe Basin 1.3 million people in the Buzi Basin 3.2 million people in the Save Basin 20 million people in Central Zambezi Poverty is a persistent problem in the Basins with more than half the rural population living below the poverty datum line 60% lack access to safe and reliable drinking water 75% lack access to proper sanitation General Overview of the Basins The water resources are unevenly distributed across the Basins, both spatially and temporally There is generally a lack of coincidence between water resources endowment and human settlement Floods and drought are a major challenge Situation exacerbated by the impact of climate change Water quality problems from improper land use practices CRIDF Interventions Responding to the needs of poor Communities and key Partners Need to protect the resource base Strengthening Institutional Capacity of key Partners through TA support Strengthening Stakeholder structures to enhance mutual trust and confidence Consolidating cooperation in Transboundary Water Resources Management CRIDF Interventions: Project Selection Transparency – stakeholders must have confidence in how projects are selected Fairness and inclusivity – every attempt is made to ensure that all stakeholders are treated fairly and processes around -

Southern Africa • Floods Regional Update # 5 20 April 2010

Southern Africa • Floods Regional Update # 5 20 April 2010 This report was issued by the Regional Office for Southern and Eastern Africa (ROSEA). It covers the period from 09 to 20 April 2010. The next report will be issued within the next two weeks. I. HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES • An assessment mission to the Angolan Province of Cunene found that 23,620 people have been affected by floods; • In Madagascar, access to affected communities remains an issue. II. Regional Situation Overview As the rainy season draws to a close, countries downstream of the Zambezi River - Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe – are not experiencing any new incidences of flooding. However, continuing high water levels in the upper Zambezi, Cunene, Cuvelai and Kavango Rivers are still being recorded, affecting Angola and northern Namibia. Furthermore, as the high water levels in the upper Zambezi River move downstream, localized flooding remains a possibility. In the next two weeks, no significant rainfall is expected over the currently flood-affected areas or their surrounding basins. III. Angola A joint assessment mission by Government and the United Nations Country Team (UNCT) was conducted in the flood-affected Cunene Province from 06 to 09 April 2010. The mission found that 23,620 people (3,300 households) have been affected by floods in the province. Of that total, 12,449 people (1,706 households) have been left homeless but have been able to stay with neighbors and family, whilst the remaining 11,171 people (1,549 households) have been relocated to Government-managed camps within the province. There are also reports of damage to schools and infrastructure. -

Mozambique Case Study Example1

Mozambique Case study example1 - Principle 1: The Zambezi River Basin - "dialogue for building a common vision" The Zambezi River Basin encompasses some 1.300 km2 throughout the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region, including a dense network of tributaries and associated wetland systems in eight countries (Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, Tanzania, Mozambique). The livelihoods of approximately 26 million people are directly dependent on this basin, deriving benefits from its water, hydro-electric power, irrigation developments, fisheries and great wealth of related natural resources, including grazing areas, wildlife, and tourism. Over the past forty years, however, the communities and ecosystems of the lower Zambezi have been constraint by the management of large upstream dams. The toll is particularly high on Mozambique, as it the last country on the journey of the Zambezi; Mozambicans have to live with the consequences of upriver management. By eliminating natural flooding and greatly increasing dry season flows in the lower Zambezi, Kariba Dam (completed in 1959) and especially Cahora Bassa Dam (completed in 1974) cause great hardship for hundreds of thousands of Mozambican villagers whose livelihoods depend on the ebb and flow of the Zambezi River. Although these hydropower dams generate important revenues and support development however, at the expense of other resource users. Subsistence fishing, farming, and livestock grazing activities have collapsed with the loss of the annual flood. The productivity of the prawn fishery has declined by $10 - 20 million per year -- this in a country that ranks as one of the world’s poorest nations (per capita income in 2000 was USD230). -

Dynamic Evolution of the Zambezi-Limpopo Watershed, Central Zimbabwe

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Online Research @ Cardiff Moore, Blenkinsop and Cotterill Zim watershed_20120408_AEM DYNAMIC EVOLUTION OF THE ZAMBEZI-LIMPOPO WATERSHED, CENTRAL ZIMBABWE Andy Moore1,2, Tom Blenkinsop3 and Fenton (Woody) Cotterill4 1African Queen Mines Ltd., Box 66 Maun, Botswana. 2Dept of Geology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown 6140, South Africa. Email: [email protected] 3School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD4811, Australia. Email: [email protected] 4AEON – African Earth Observatory Network, Geoecodynamics Research Hub, University of Stellenbosch, Private Bag X1, Matieland 7602, South Africa. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Prospecting carried out to the south of the Zambezi-Limpopo drainage divide in the vicinity of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, led to the recovery of a suite of ilmenites with a chemical “fingerprint” that can be closely matched with the population found in the early Palaeozoic Colossus kimberlite, which is located to the north of the modern watershed. The ilmenite geochemistry eliminates other Zimbabwe Kimberlites as potential sources of these pathfinder minerals. Geophysical modelling has been used to ascribe the elevation of southern Africa to dynamic topography sustained by a mantle plume; however, the evolution of the modern divide between the Zambezi and Limpopo drainage basins is not readily explained in terms of this model. Rather, it can be interpreted to represent a late Palaeogene continental flexure, which formed in response to crustal shortening, linked to intra-plate transmission of stresses associated with an episode of spreading reorganization at the ocean ridges surrounding southern Africa. -

High Potential in the Lower Zambezi

2 High Potential in the Lower Zambezi A way forward to sustainable development Version 1.0 High Potential in the Lower Zambezi High Potential in the Lower Zambezi A way forward to sustainable development Delta Alliance Delta Alliance is an international knowledge network with the mission of improving the resilience of the world’s deltas, by bringing together people who live and work in the deltas. Delta Alliance has currently ten network Wings worldwide where activities are focused. Delta Alliance is exploring the possibility to connect the Zambezi Delta to this network and to establish a network Wing in Mozambique. WWF WWF is a worldwide organization with the mission to stop the degradation of the planet’s natural environment and build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature. WWF recently launched (June 2010) the World Estuary Alliance (WEA). WEA focuses on knowledge exchange and information sharing on the value of healthy estuaries and maximiza- tion of the potential and benefits of ‘natural systems’ in sustainable estuary development. In Mozambique WWF works amongst others in the Zambezi Basin and Delta on environmental flows and mangrove conservation. Frank Dekker (Delta Alliance) Wim van Driel (Delta Alliance) From 28 August to 2 September 2011, WWF and Delta Alliance have organized a joint mission to the Lower Zambezi Basin and Delta, in order to contribute to the sustainable development, knowing that large developments are just emerging. Bart Geenen (WWF) The delegation of this mission consisted of Companies (DHV and Royal Haskoning), NGOs (WWF), Knowledge Institutes (Wageningen University, Deltares, Alterra, and Eduardo Mondlane University) and Government Institutes (ARA Zambeze). -

Glimpopo Fact Sheet

Fact Sheet 1 The Limpopo River flows over a total distance of The Limpopo basin covers almost 14 percent of the total 1,750 kilometres. It starts at the confluence of the Marico area of its four riparian states – Botswana, South Africa, and Crocodile rivers in South Africa and flows northwest Zimbabwe and Mozambique. And of the basin’s total area, of Pretoria. It is joined by the Notwane river flowing from 44 percent is occupied by South Africa, 21 percent by Botswana, and then forms the border between Botswana Mozambique, almost 20 percent by Botswana and 16 per- and South Africa, and flows in a north easterly direction. cent by Zimbabwe. At the confluence of the Shashe river, which flows in from Zimbabwe and Botswana, the Limpopo turns almost due Drainage Network The Limpopo river has a rela- east and forms the border between Zimbabwe and South tively dense network of more than 20 tributary streams and Africa before entering Mozambique at Pafuri. For the next rivers, though most of these tributaries have either season- 561 km the river flows entirely within Mozambique and al or episodic flows. In historical times, the Limpopo river enters the Indian Ocean about 60 km downstream of the was a strong-flowing perennial river but is now regarded town of Xai-Xai. as a weak perennial river where flows frequently cease. During drought periods, no surface water is present over The Basin The Limpopo river basin is almost circular large stretches of the middle and lower reaches of the in shape with a mean altitude of 840 m above sea level. -

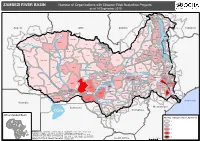

ZAMBEZI RIVER BASIN Number of Organizations with Disaster Risk Reduction Projects As at 14 September 2010

ZAMBEZI RIVER BASIN Number of Organizations with Disaster Risk Reduction Projects as at 14 September 2010 Rural Urban Mbozi Rungwe Makete Njombe Ileje Nakonde Kyela Chitipa Karonga Ludewa Isoka Songea Rural Namtumbo Angola DRC Zambia Mbinga Songea Tanzania Dala Rumphi Urban Luau Chinsali Chama Kamanongue Luakano Nkhata Bay Leua Zambezi Lake Malawi Kuemba Kameia Mwinilunga Mzimba Ilha Risunodo Likoma Sanga Mpika Lungue-Bongo Alto Zambeze Moxico Lago Solwezi Chililabombwe Chingola Lundazi Kamakupa Mufulira Kalulushi Kitwe Malawi Lufwanyama Ndola Nkhotakota Luanshya Chavuma Kasungu Lichinga Zambezi Kabompo Luangwa Serenje Ntchisi Cidade De Lichinga Masaiti Mambwe Kafue Mpongwe Chipata Dowa Kasempa Luxazes Mchinji Salima Mufumbwe Ngauma Petauke Lilongwe Kapiri Mposhi Chadiza Mkushi Katete Lumbala-Nguimbo Lukulu Dedza Nyimba Mangochi Kabwe Chifunde Angonia Lake Malombe Macanga Ntcheu Chibombo Kuito Kuanavale Shire Machinga Kalabo Kaoma Mumbwa Balaka Maravia Cuando Mongu Zumbu Tsang an o Chongwe Lusaka Zomba Luangwa Chiuta Neno Phalombe Kafue Cahora Bassa Dam Mwanza Blantyre Milange Chiradzulu Zambezi Moatize Senanga Itezhi-Tezhi Namwala Mazabuka Magoe Mulanje Angwa Cahora Bassa Thyolo Mavinga Mbire Cidade De Tete Monze Zambezi Chikwawa Siavonga Zambezi Centenary Changara Nancova Hurungwe Mt.Darwin Shang’ombo Guruve Ruya Rushinga Luenha Mutarara Sesheke Choma Gwembe Morrumbala Sanyati Nsanje Rivungo Luenha UMP Guro Ta m b a r a Kazungula Lake Kariba Kariba Musengezi Mudzi Shamva Chire Kalomo Chemba Dirico Makonde Mazowe Bindura Machile Ruenya -

Shared Watercourses Support Project for Buzi, Save and Ruvuma River Basins

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND Language: English Original: English MULTINATIONAL SADC SHARED WATERCOURSES SUPPORT PROJECT FOR BUZI, SAVE AND RUVUMA RIVER BASINS APPRAISAL REPORT INFRASTRUCTURE DEPARTMENT NORTH, EAST, AND SOUTH REGION SEPTEMBER 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page BASIC PROJECT DATA/ EQUIVALENTS AND ABBREVIATIONS /LIST OF ANNEXES/TABLES/ BASIC DATA, MATRIX EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i-xiii 1. HISTORY AND ORIGIN OF THE PROJECT 1 2. THE SADC WATER SECTOR 2 2.1 Sector Organisation 2 2.2 Sector Policy and Strategy 3 2.3 Water Resources 4 2.4 Sector Constraints 4 2.5 Donor Interventions 5 2.6 Poverty, Gender HIV AND AIDS, Malaria and Water Resources 6 3. TRANSBOUNDARY WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT 7 4. THE PROJECT 10 4.1 Project Concept and Rationale 10 4.2 Project Area and Beneficiaries 11 4.3 Strategic Context 13 4.4 Project Objective 14 4.5 Project Description 14 4.6 Production, Market, and Prices 18 4.7 Environmental Impact 18 4.8 Social Impact 19 4.9 Project Costs 19 4.10 Sources of Finance 20 5. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 21 5.1 Executing Agency 21 5.2 Implementation Schedule and Supervision 23 5.3 Procurement Arrangements 23 5.4 Disbursement Arrangement 25 5.5 Monitoring and Evaluation 26 5.6 Financial Reporting and Auditing 27 5.7 Donor Coordination 27 6. PROJECT SUSTAINABILITY 27 6.1 Recurrent Costs 27 6.2 Project Sustainability 28 6.3 Critical Risks and Mitigation Measures 28 7. PROJECT BENEFITS 7.1 Economic Benefits 29 7.2 Social Impacts 29 i 8. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 8.1 Conclusions 30 8.2 Recommendations 31 ___________________________________________________________________________ This report was prepared following an Appraisal Mission to SADC by Messrs Egbert H.J.