Arxiv:1912.00684V1 [Physics.Optics] 2 Dec 2019 Sacntan Ntesals Oa Ptwt Ieabout Size with Wavelength Spot Used Focal the It Smallest of [4]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Numerical Study of Resolution and Contrast in Soft X-Ray Contact Microscopy

Journal of Microscopy, Vol. 191, Pt 2, August 1998, pp. 159–169. Received 24 April 1997; accepted 12 September 1997 A numerical study of resolution and contrast in soft X-ray contact microscopy Y.WANG&C.JACOBSEN Department of Physics, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY 11794-3800, U.S.A. Key words. Contrast, photoresists, resolution, soft X-ray microscopy. Summary In this paper we consider the nature of contact X-ray micrographs recorded on photoresists, and the limitations We consider the case of soft X-ray contact microscopy using on image resolution imposed by photon statistics, diffrac- a laser-produced plasma. We model the effects of sample tion and by the process of developing the photoresist. and resist absorption and diffraction as well as the process Numerical simulations corresponding to typical experimen- of isotropic development of the photoresist. Our results tal conditions suggest that it is difficult to reliably interpret indicate that the micrograph resolution depends heavily on details below the 40 nm level by these techniques as they the exposure and the sample-to-resist distance. In addition, now are frequently practised. the contrast of small features depends crucially on the development procedure to the point where information on such features may be destroyed by excessive development. 2. X-ray contact microradiography These issues must be kept in mind when interpreting contact microradiographs of high resolution, low contrast There is a long history of research in which X-ray objects such as biological structures. radiographs have been viewed with optical microscopes to study submillimetre structures (Gorby, 1913). -

Basic Diffraction Phenomena in Time Domain

Basic diffraction phenomena in time domain Peeter Saari,1 Pamela Bowlan,2,* Heli Valtna-Lukner,1 Madis Lõhmus,1 Peeter Piksarv,1 and Rick Trebino2 1Institute of Physics, University of Tartu, 142 Riia St, Tartu, 51014, Estonia 2School of Physics, Georgia Institute of Technology, 837 State St NW, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA *[email protected] Abstract: Using a recently developed technique (SEA TADPOLE) for easily measuring the complete spatiotemporal electric field of light pulses with micrometer spatial and femtosecond temporal resolution, we directly demonstrate the formation of theo-called boundary diffraction wave and Arago’s spot after an aperture, as well as the superluminal propagation of the spot. Our spatiotemporally resolved measurements beautifully confirm the time-domain treatment of diffraction. Also they prove very useful for modern physical optics, especially in micro- and meso-optics, and also significantly aid in the understanding of diffraction phenomena in general. ©2010 Optical Society of America OCIS codes: (320.5550) Pulses; (320.7100) Ultrafast measurements; (050.1940) Diffraction. References and links 1. G. A. Maggi, “Sulla propagazione libera e perturbata delle onde luminose in mezzo isotropo,” Ann. di Mat IIa,” 16, 21–48 (1888). 2. A. Rubinowicz, “Thomas Young and the theory of diffraction,” Nature 180(4578), 160–162 (1957). 3. g. See, monograph M. Born and E. Wolf, Principles of Optics (Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1987, 6th ed) and references therein. 4. Z. L. Horváth, and Z. Bor, “Diffraction of short pulses with boundary diffraction wave theory,” Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 63(2), 026601 (2001). 5. P. Bowlan, P. Gabolde, A. -

Chapter 22 Wave Optics

Chapter 22 Wave Optics Chapter Goal: To understand and apply the wave model of light. © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Slide 22-2 © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Models of Light . The wave model: Under many circumstances, light exhibits the same behavior as sound or water waves. The study of light as a wave is called wave optics. The ray model: The properties of prisms, mirrors, and lenses are best understood in terms of light rays. The ray model is the basis of ray optics. Chapter 23 . The photon model: In the quantum world, light behaves like neither a wave nor a particle. Instead, light consists of photons that have both wave-like and particle-like properties. This is the quantum theory of light. Physics 43 © 2013 Pearson Education, Inc. Slide 22-29 Diffraction depends on SLIT WIDTH: the smaller the width, relative to wavelength, the more bending and diffraction. Ray Optics: Ignores Diffraction and Interference of waves! Diffraction depends on SLIT WIDTH: the smaller the width, relative to wavelength, the more bending and diffraction. Ray Optics assumes that λ<<d , where d is the diameter of the opening. This approximation is good for the study of mirrors, lenses, prisms, etc. Wave Optics assumes that λ~d , where d is the diameter of the opening. d>1mm: This approximation is good for the study of interference. Geometric RAY Optics (Ch 23) nn1sin 1 2 sin 2 ir James Clerk Maxwell 1860s Light is wave. Speed of Light in a vacuum: 1 8 186,000 miles per second c3.0 x 10 m / s 300,000 kilometers per second 0 o 3 x 10^8 m/s Intensity of Light Waves E = Emax cos (kx – ωt) B = Bmax cos (kx – ωt) E ωE max c Bmax k B E B E22 c B I S maxmax max max 2 av 2μ 2 μ c 2 μ o o o I E m ax The Electromagnetic Spectrum Visible Light • Different wavelengths correspond to different colors • The range is from red (λ ~ 7 x 10-7 m) to violet (λ ~4 x 10-7 m) Limits of Vision Electron Waves 11 e 2.4xm 10 Interference of Light Wave Optics Double Slit is VERY IMPORTANT because it is evidence of waves. -

The Double Slit Experiment Re-Explained

IOSR Journal of Applied Physics (IOSR-JAP) e-ISSN: 2278-4861.Volume 8, Issue 4 Ver. III (Jul. - Aug. 2016), PP 86-98 www.iosrjournals.org The Double Slit Experiment Re-Explained Mahmoud E. Yousif Physics Department - The University of Nairobi P.O.Box 30197 Nairobi-Kenya Abstract: The wavelet envisioned by Huygen’s in diffraction phenomenon is re-interpreted as a Polarized Wave (PW) after passing through slit/hole/or biaxial crystals which removed the electric field component from the Electromagnetic Radiation (EM-R), the resulted wave is what is known as the Conical Diffraction (CD) beam, the PW is originated from the Circular Magnetic Field (CMF) produced by accelerated electrons, integrated with the Electric Field (EF) during the Flip-Flop (F-F) mechanism producing EM-R; hence the passing of light through a single hole/slit/biaxial crystals, resulted in a PW which reproduced as rings on the monitor screen in single wave diffraction, while the interference of two such PW in double slits experiment, produced constructive or destructive interference forming patches on the monitor screen; and the perceived electron diffraction is an enter of two CMF from an accelerated electron into two slits then emerged to interfere constructively or destructively, and appears as patches, in addition to the electron which entered and emerged from the slit with the intense CMF, the paper finally derived the origin of Planck’ constant (h) for the second time; the logical interpretation of double slits diffraction will restore the common sense in the physical world, distorted by the pilot wave. Keywords: Double Slit Experiment; wavelet; Circular Magnetic Field; electron diffraction; polarization; origin of Planck’ constant. -

Observation of the Poisson Spot Abstract

Observation of the Poisson Spot Abstract The first-time observation of Poisson’s (or Arago’s) spot in 1818 constituted one of the most relevant experiments in the history of optics, helping discard the (at the time) favoured position of attributing a corpuscular nature to light. When Fresnel presented his theory of diffraction before the French Academy of Sciences, Poisson, a member of the committee, scoffed at the fact that Fresnel’s approach predicted a bright spot in the shadow of a circular obstacle placed in the way of a beam of light. And sure enough, as fellow committee member Arago demonstrated, this spot could be observed experimentally. 2 www.LightTrans.com Modeling Task opaque obstacle Geometrical optics predicts only darkness in the geometric (100 mm) d = 100 mm shadow of the obstacle. Physical optics, however, considers diffraction from the edges of the obstacle… collimated beam (wavelength l = 532 nm) Condition of observation 3 Observation of the Poisson spot opaque obstacle (100 mm) d = 100 mm D =2mm collimated beam (wavelength l = 532 nm) It is only diffraction from the edges what permits light to travel to the geometric shadow of the obstacle! 4 Observation of the Poisson spot opaque obstacle (100 mm) d = 100 mm D =2mm Poisson spot collimated beam (wavelength l = 532 nm) It is only diffraction from the edges what permits light to travel to the geometric shadow of the obstacle! 5 Evolution of Diffraction Pattern and Appearance of the Spot … D=100um – 2.1mm Previous result D=2mm 6 Evolution of Diffraction Pattern and Appearance of the Spot … D = 100 um – 2.1 mm 7 Peek into VirtualLab Fusion Generate animation to better investigate the effect of a third independent variable Parameter Run to investigate evolution of diffraction pattern with screen position 8 Workflow in VirtualLab Fusion • Configure the Camera Detector − Usage of Camera Detector [Use Case] • Set up the Parameter Run − Usage of the Parameter Run document [Use Case] • Create the animation − Animation generation with Par. -

The Fresnel Diffraction: a Story of Light and Darkness C

New Concepts in Imaging: Optical and Statistical Models D. Mary, C. Theys and C. Aime (eds) EAS Publications Series, 59 (2013) 37–58 THE FRESNEL DIFFRACTION: A STORY OF LIGHT AND DARKNESS C. Aime1, E.´ Aristidi1 and Y. Rabbia1 Abstract. In a first part of the paper we give a simple introduction to the free space propagation of light at the level of a Master degree in Physics. The presentation promotes linear filtering aspects at the expense of fundamental physics. Following the Huygens-Fresnel ap- proach, the propagation of the wave writes as a convolution relation- ship, the impulse response being a quadratic phase factor. We give the corresponding filter in the Fourier plane. As an illustration, we describe the propagation of wave with a spatial sinusoidal amplitude, introduce lenses as quadratic phase transmissions, discuss their Fourier transform properties and give some properties of Soret screens. Clas- sical diffractions of rectangular diaphragms are also given here. In a second part of the paper, the presentation turns into the use of exter- nal occulters in coronagraphy for the detection of exoplanets and the study of the solar corona. Making use of Lommel series expansions, we obtain the analytical expression for the diffraction of a circular opaque screen, giving thereby the complete formalism for the Arago-Poisson spot. We include there shaped occulters. The paper ends up with a brief application to incoherent imaging in astronomy. 1 Historical introduction The question whether the light is a wave or a particle goes back to the seven- teenth century during which the mechanical corpuscular theory of Newton took precedence over the wave theory of Huygens. -

On the Relative Intensity of Poisson's Spot

Home Search Collections Journals About Contact us My IOPscience On the relative intensity of Poisson’s spot This content has been downloaded from IOPscience. Please scroll down to see the full text. 2017 New J. Phys. 19 033022 (http://iopscience.iop.org/1367-2630/19/3/033022) View the table of contents for this issue, or go to the journal homepage for more Download details: IP Address: 129.13.72.198 This content was downloaded on 10/07/2017 at 09:57 Please note that terms and conditions apply. You may also be interested in: Particle–wave discrimination in Poisson spot experiments T Reisinger, G Bracco and B Holst Photon field and energy flow lines behind a circular disc D Arsenovi, D Dimic and M Boži ANALYTIC MODELING OF STARSHADES Webster Cash Experimental methods of molecular matter-wave optics Thomas Juffmann, Hendrik Ulbricht and Markus Arndt Rayleigh--Sommerfeld diffraction and Poisson's spot Robert L Lucke A micromechanical optical switch with a zone-plate reflector Dennis S Greywall Super-resolution microscopy of single atoms in optical lattices Andrea Alberti, Carsten Robens, Wolfgang Alt et al. Hands-on Fourier analysis by means of far-field diffraction Nicolo’ Giovanni Ceffa, Maddalena Collini, Laura D’Alfonso et al. Optimizing Fourier filtering for digital holographic particle image velocimetry Thomas Ooms, Wouter Koek, Joseph Braat et al. New J. Phys. 19 (2017) 033022 https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/aa5e7f PAPER On the relative intensity of Poisson’s spot OPEN ACCESS T Reisinger1, P M Leufke, H Gleiter and H Hahn RECEIVED Institute of Nanotechnology, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Hermann-von-Helmholtz-Platz 1, D-76344 Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, 16 November 2016 Germany REVISED 1 Author to whom any correspondence should be addressed. -

Direct Imaging of Exoplanets

Direct Imaging of Exoplanets Wesley A. Traub Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology Ben R. Oppenheimer American Museum of Natural History A direct image of an exoplanet system is a snapshot of the planets and disk around a central star. We can estimate the orbit of a planet from a time series of images, and we can estimate the size, temperature, clouds, atmospheric gases, surface properties, rotation rate, and likelihood of life on a planet from its photometry, colors, and spectra in the visible and infrared. The exoplanets around stars in the solar neighborhood are expected to be bright enough for us to characterize them with direct imaging; however, they are much fainter than their parent star, and separated by very small angles, so conventional imaging techniques are totally inadequate, and new methods are needed. A direct-imaging instrument for exoplanets must (1) suppress the bright star’s image and diffraction pattern, and (2) suppress the star’s scattered light from imperfections in the telescope. This chapter shows how exoplanets can be imaged by controlling diffraction with a coronagraph or interferometer, and controlling scattered light with deformable mirrors. 1. INTRODUCTION fainter than its star, and separated by 12.7 arcsec (98 AU at 7.7 pc distance). It was detected at two epochs, clearly showing The first direct images of exoplanets were published in common motion as well as orbital motion (see inset). 2008, fully 12 years after exoplanets were discovered, and Figure 2 shows a near-infrared composite image of exo- after more than 300 of them had been measured indirectly planets HR 8799 b,c,d by Marois et al. -

Arago Spot Formation in the Time Domain Christophe Finot, Hervé Rigneault

Arago spot formation in the time domain Christophe Finot, Hervé Rigneault To cite this version: Christophe Finot, Hervé Rigneault. Arago spot formation in the time domain. Journal of Optics, Institute of Physics (IOP), 2019, 21 (10), pp.105504. 10.1088/2040-8986/ab4105. hal-02017978 HAL Id: hal-02017978 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02017978 Submitted on 13 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arago spot formation in the time domain C Finot 1 and H Rigneault 2 1 Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire Carnot de Bourgogne, UMR 6303 CNRS - Université de Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, 9 avenue Alain Savary, BP 47870, 21078 Dijon Cedex, France 2 Aix Marseille Université, CNRS, Centrale Marseille, Institut Fresnel UMR 7249, 13397 Marseille, France E-mail : [email protected] Abstract. Using the space-time duality we theoretically and experimentally revisit the Arago spot formation in the time domain and explore the temporal emergence of a bright spot in the time shadow of an initial waveform. We describe the linear regime of propagation using Fresnel’s integrals and show that in the presence of Kerr nonlinearity the Arago spot formation is affected depending on the sign of the dispersion. -

The Experimental Origins of Quantum Mechanics

This is page 1 Printer: Opaque this 1 The experimental origins of quantum mechanics Quantum mechanics, with its controversial probabilistic nature and curi- ous blending of waves and particles, is a very strange theory. It was not invented because anyone thought this is the way the world should behave, but because various experiments showed that this is the way the world does behave, like it or not. Craig Hogan, director of the Fermilab Particle Astrophysics Center, puts it this way: No theorist in his right mind would have invented quantum mechanics unless forced to by data.1 Although the first hint of quantum mechanics came in 1900 with Planck’s solution to the problem of blackbody radiation, the full theory did not emerge until 1925 and 1926, with the Heisenberg’s matrix model, Schrödinger’s wave model, and Born’s statistical interpretation of the wave model. 1.1 Is light a wave or a particle? 1.1.1 Newton versus Huygens Beginning in the late 17th century and continuing into the early 18th cen- tury, there was a vigorous debate in the scientific community over the 1 Quoted in “Is Space Digital?” by Michael Moyer, Scientific American, February 2012, pp. 30-36. 2 1. The experimental origins of quantum mechanics nature of light. One camp, following the views of Isaac Newton, claimed that light consisted of a group of particles or “corpuscles.” The other camp, led by the Dutch physicist Christiaan Huygens, claimed that light was a wave. Newton argued that only a corpuscular theory could account for the observed tendency of light to travel in straight lines. -

Fresnel and Fraunhofer Diffraction

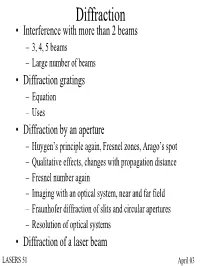

Diffraction • Interference with more than 2 beams – 3, 4, 5 beams – Large number of beams • Diffraction gratings – Equation –Uses • Diffraction by an aperture – Huygen’s principle again, Fresnel zones, Arago’s spot – Qualitative effects, changes with propagation distance – Fresnel number again – Imaging with an optical system, near and far field – Fraunhofer diffraction of slits and circular apertures – Resolution of optical systems • Diffraction of a laser beam LASERS 51 April 03 Interference from multiple apertures L Bright fringes when OPD=nλ 40 x nLλ d x = d Intensity source OPD two slits position on screen screen Complete destructive interference halfway between OPD 1 OPD 1=nλ, OPD 2=2nλ OPD 2 all three waves40 interfere constructively d Intensity source three position on screen equally spaced slits screen OPD 2=nλ, n odd outer slits constructively interfere middle slit gives secondary maxima LASERS 51 April 03 Diffraction from multiple apertures • Fringes not sinusoidal for more than two slits 2 slits • Main peak gets narrower – Center location obeys same 3 slits equation • Secondary maxima appear 4 slits between main peaks – The more slits, the more 5 slits secondary maxima – The more slits, the weaker the secondary maxima become • Diffraction grating – many slits, very narrow spacing – Main peaks become narrow and widely spaced – Secondary peaks are too small to observe LASERS 51 April 03 Reflection and transmission gratings • Transmission grating – many closely spaced slits • Reflection grating – many closely spaced reflecting -

Reproducing the Fresnel-Arago Experiment to Illustrate Physical Optics

PIONEERING EXPERIMENT REPRODUCING THE FRESNEL-ARAGO EXPERIMENT TO ILLUSTRATE PHYSICAL OPTICS /////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Jérôme WENGER*, Benoît ROGEZ, Thomas CHAIGNE, Brian STOUT Aix Marseille Univ, CNRS, Centrale Marseille, Institut Fresnel, Marseille, France * [email protected] Is there a bright spot in the shadow of an opaque disk? Nearly 200 years ago, Augustin Fresnel and François Arago’s remarkable answer to this question validated the wave theory of light and inaugurated the modern theories of diffraction. Today, their renowned experiment can be easily reproduced using lasers and cameras. Far beyond its historical interest, the experiment is a versatile platform to illustrate the main concepts of optical physics, including diffraction, interference, speckle, and Fourier optics. https://doi.org/10.1051/photon/202010421 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. INTRODUCTION: A BRIEF of scientists who favoured Newton’s spot at the centre of the shadow of HISTORICAL BACKGROUND particle theory. Amongst their ranks an opaque disk, which he held to ABOUT FRESNEL-ARAGO was Siméon Poisson who thought he be clearly false [3]. Fresnel realized EXPERIMENT had debunked Fresnel’s theory when however that shadows in every- At the beginning of the 19th centu- he remarked that it predicts a bright day life generally lack the spatial ry, Newton’s corpuscular theory of light was hard pressed to explain Thomas Young’s observations of in- terference fringes by light passing through double slits.