The FNAC-DARTY Merger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An N U Al R Ep O R T 2018 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 ANNUAL REPORT The Annual Report in English is a translation of the French Document de référence provided for information purposes. This translation is qualified in its entirety by reference to the Document de référence. The Annual Report is available on the Company’s website www.vivendi.com II –— VIVENDI –— ANNUAL REPORT 2018 –— –— VIVENDI –— ANNUAL REPORT 2018 –— 01 Content QUESTIONS FOR YANNICK BOLLORÉ AND ARNAUD DE PUYFONTAINE 02 PROFILE OF THE GROUP — STRATEGY AND VALUE CREATION — BUSINESSES, FINANCIAL COMMUNICATION, TAX POLICY AND REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT — NON-FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE 04 1. Profile of the Group 06 1 2. Strategy and Value Creation 12 3. Businesses – Financial Communication – Tax Policy and Regulatory Environment 24 4. Non-financial Performance 48 RISK FACTORS — INTERNAL CONTROL AND RISK MANAGEMENT — COMPLIANCE POLICY 96 1. Risk Factors 98 2. Internal Control and Risk Management 102 2 3. Compliance Policy 108 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE OF VIVENDI — COMPENSATION OF CORPORATE OFFICERS OF VIVENDI — GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE COMPANY 112 1. Corporate Governance of Vivendi 114 2. Compensation of Corporate Officers of Vivendi 150 3 3. General Information about the Company 184 FINANCIAL REPORT — STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT ON THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — STATUTORY FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 196 Key Consolidated Financial Data for the last five years 198 4 I – 2018 Financial Report 199 II – Appendix to the Financial Report 222 III – Audited Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended December 31, 2018 223 IV – 2018 Statutory Financial Statements 319 RECENT EVENTS — OUTLOOK 358 1. Recent Events 360 5 2. Outlook 361 RESPONSIBILITY FOR AUDITING THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 362 1. -

Agenda Cultural Fnac Maig El Triangle

canta al seu poble i busca la llum. Un àlbum concebut per tal de mostrar- Agenda Cultural EXPOSICIÓN se nua, sincera i compromesa amb TRIANGLE MAIG MAYO 2018 HASTA EL 31 DE MAYO el moment que viu. FLAMINGO TOURS “Lucha libre” Jueves 3 19:00h “ESTAMOS TODAS BIEN” Este nuevo álbum de Flamingo Tours De Ana Penyas. Premio tiene pocas concesiones a la inocen- Internacional Fnac-Salamandra cia, transitando por las venas profun- Graphic de Novela Gráfica y das del rock‘n’roll con cara de mujer, los pantanos del blues, el soul viejo, Premio Autor Revelación del DAVID OTERO la cocina tex-mex y un poquito de sa- Saló del Cómic de Barcelona. “1980” tanspell y de rhythm & blues. Raíces En palabras de Ana Penyas (Valencia, Dimarts 22 19:00h americanas, amor hillbilly, desiertos de 1987): “En ningún momento de los tres El nuevo álbum de David Otero no solo Nuevo Mejico y las fronteras de la piel. años que me ha llevado este proyecto ha viajado en el tiempo sino que tam- pensé que iba a exponer los originales. bién en el espacio. Nació en Portugal, “MANHATTAN” Lo que sí que he tenido tiempo de pensar creció en Marruecos y fue grabado De Diego Ojeda es en todo lo que me ha aportado: sentir a caballo entre Madrid y Barcelona. Jueves 24 19:00h el pasado, empatizar con mis abuelas, Mezclado en Toronto por Gabe Ga- Hace más de un año, el cantautor y poeta canario, precursor del movimiento poético actual, empezó a trabajar comprender su mundo, etc. -

FEAT Guide Round 3

Stop Touting A Guide to Personalised Tickets in Europe Contents 1. Introduction 2. Foreword 3. Step by step guide to personalising tickets 4. Individual country overview 5. Further resources 6. About FEAT Welcome If you think secondary ticketing isn’t a problem, you’d be wrong. The market was valued at €1.66bn in 2020 for Europe despite Covid, and is predicted to grow to €2.29bn by 2023 (Intellectual Research Partners). This is money drained from the live business, negatively impacting future Navigating the rules and customs of Europe can be a mineeld, especially ticket sales, bar revenues and the sale of merchandise. It also aects your when it comes to secondary ticketing. But if you scratch the surface, you’ll reputation and the trust that fans put in you, and ultimately the artist nd that it takes just a few steps and some teamwork to make sure that they’ve tried desperately to see. your tickets end up in the hands of real fans and not touts. By following the easy steps outlined in this guide, we hope to make it That’s where this guide comes in. easier to understand the landscape across Europe and how to protect your inventory, and fans, from touts. “Stop Touting: A Guide to Personalised Tickets in Europe" outlines some easy steps that you can take minimise scalping and build a fair and reliable This guide is intended as purely a summary to show that personalisation resale system for your shows. can be done successfully, without putting your neck on the line or needing a degree in ticket resale. -

Muse Confirmed As the First Headline Group for the Nos Alive'15 Concert

PRESS RELEASE 11 / 11 / 2014 MUSE CONFIRMED AS THE FIRST HEADLINE GROUP FOR THE NOS ALIVE’15 CONCERT LINE UP Muse is the first headline group confirmed for NOS Alive’15. The British group, considered to be one of the biggest rock bands at the moment and known for its impressive productions and live performances, will perform on the NOS stage on the 9 th of July. The band, made up by Matthew Bellamy (voice, guitar and piano), Christopher Wolstenholme (bass, voice and keyboard) and Dominic Howard (drums and percussion), have already published six albums of original songs, selling more than 20 million copies across the world. The group is currently working in the studio preparing their seventh LP whose launch is planned for 2015. Throughout their career, Muse has won numerous prizes, among which five “MTV Europe Music Awards”, six “NME Awards” and six “Q Awards”. They were also considered twice as the "Best British Live Act" at the Brit Awards, and were also nominated for five “Grammy Awards”, where they won “Best Rock Album”, with the disc “The Resistance”. The group began its last tour, presenting its sixth disc of original songs, in October 2012, performing for more than two million fans. Portugal was one of the countries visited with a single concert in the “Estádio do Dragão” (FC Porto’s football stadium). Confirmed artists: alt-J, Muse. Direção de Comunicação Corporativa & Sustentabilidade PRESS LINK Edifício Campo Grande, João Pinho Rua Ator António Silva, 9, Piso 6, Lisboa [email protected] T 217 824 700 | comunicaçã[email protected] -

French Retailer Darty Boosts Margins Via Its Online Marketplace by Sucharita Mulpuru August 17, 2016

FOR EBUSINESS & CHANNEL STRATEGY PROFESSIONALS Case Study: French Retailer Darty Boosts Margins Via Its Online Marketplace by Sucharita Mulpuru August 17, 2016 Why Read This Report Key Takeaways Third-party marketplaces have a reputation for C-Level Support Is Essential For Successful being lucrative, but many large multichannel Marketplace Execution retailers still struggle to drive much success Darty was able to launch its marketplace after a few after developing their own marketplaces. months of IT development work because the CEO This document analyzes the challenges and of the company explicitly endorsed the initiative. successes of French retailer Darty, which has Profits Are Likely But Not Always Large executed its marketplace well, and provides Darty’s sales from its marketplace are more lessons for other retailers as they develop their profitable than sales from owned inventory, but own marketplace strategies. the overall volume of marketplace revenue is still modest. FORRESTER.COM FOR EBUSINESS & CHANNEL STRATEGY PROFESSIONALS Case Study: French Retailer Darty Boosts Margins Via Its Online Marketplace by Sucharita Mulpuru with Fiona Swerdlow, Claudia Tajima, and Peggy Dostie August 17, 2016 Marketplaces On Retail Sites Evoke Mixed Reactions When eBusiness pros allocate and execute with adequate resources, they position themselves to experience great success with their third-party marketplaces. For years, Forrester has evangelized the idea of online marketplaces for multicategory retailers.1 Marketplaces let retailers expand their -

Deloitte Studie

Global Powers of Retailing 2018 Transformative change, reinvigorated commerce Contents Top 250 quick statistics 4 Retail trends: Transformative change, reinvigorated commerce 5 Retailing through the lens of young consumers 8 A retrospective: Then and now 10 Global economic outlook 12 Top 10 highlights 16 Global Powers of Retailing Top 250 18 Geographic analysis 26 Product sector analysis 30 New entrants 33 Fastest 50 34 Study methodology and data sources 39 Endnotes 43 Contacts 47 Global Powers of Retailing identifies the 250 largest retailers around the world based on publicly available data for FY2016 (fiscal years ended through June 2017), and analyzes their performance across geographies and product sectors. It also provides a global economic outlook and looks at the 50 fastest-growing retailers and new entrants to the Top 250. This year’s report will focus on the theme of “Transformative change, reinvigorated commerce”, which looks at the latest retail trends and the future of retailing through the lens of young consumers. To mark this 21st edition, there will be a retrospective which looks at how the Top 250 has changed over the last 15 years. 3 Top 250 quick statistics, FY2016 5 year retail Composite revenue growth US$4.4 net profit margin (Compound annual growth rate CAGR trillion 3.2% from FY2011-2016) Aggregate retail revenue 4.8% of Top 250 Minimum retail Top 250 US$17.6 revenue required to be retailers with foreign billion among Top 250 operations Average size US$3.6 66.8% of Top 250 (retail revenue) billion Composite year-over-year retail 3.3% 22.5% 10 revenue growth Composite Share of Top 250 Average number return on assets aggregate retail revenue of countries with 4.1% from foreign retail operations operations per company Source: Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited. -

A Prospective Cohort Study to Assess the Role of FDG-PET in Differentiating Benign and Malignant Follicular Neoplasms

Annals of Medicine and Surgery 12 (2016) 27e31 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Annals of Medicine and Surgery journal homepage: www.annalsjournal.com A prospective cohort study to assess the role of FDG-PET in differentiating benign and malignant follicular neoplasms * K. Alok Pathak a, c, , Andrew L. Goertzen b, Richard W. Nason a, Thomas Klonisch c, William D. Leslie b a Division of Surgical Oncology, Cancer Care Manitoba & University of Manitoba, Winnipeg Canada b Section of Nuclear Medicine, Department of Radiology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg Canada c Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Science, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg Canada highlights Earlier meta-analyses have not considered Hürthle cell neoplasm separate from other follicular neoplasm. Hürthle cell neoplasm are known to show high FDG uptake. FDG-PET/CT can help in differentiating benign and malignant non-Hürthle cell thyroid nodules. A cut-off SUVmax of 3.25 enhances the accuracy of FDG-PET/CT in identifying cancers in thyroid nodules. article info abstract Article history: Background: Follicular and Hürthle cell neoplasms are diagnostic challenges. This prospective study was Received 2 September 2016 designed to evaluate the efficacy of [18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomog- Received in revised form raphy/computed tomography (PET/CT) in predicting the risk of malignancy in follicular/Hürthle cell 26 October 2016 neoplasms. Accepted 27 October 2016 Materials and methods: Fifty thyroid nodules showing follicular/Hürthle cell neoplasm on prior ultra- sonography guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) were recruited into this study. A FDG-PET/CT Keywords: scan, performed for neck and superior mediastinum, was reported by a single observer, blinded to the Diagnosis fi Outcome surgical and pathology ndings. -

Fnac and Deezer Announce a Strategic Alliance

Press Release – Tuesday, March 14, 2017 FNAC AND DEEZER ANNOUNCE A STRATEGIC ALLIANCE FNAC, a leading distributor of cultural and technical products, and Deezer, the world’s most diverse, dynamic and personal music streaming company, have announced an exclusive long-term international strategic alliance, designed to strengthen their leadership in the music market. As part of this strategic partnership, Fnac may become a Deezer shareholder. The evolution of the music market continues with the growth of digital, where streaming (which complements usage in the physical and live market) is now the dominant method of consumption. As a result of this, Fnac, the top music store and ticket vendor in France, and Deezer have decided to join forces in order to bolster the growth of their respective businesses. The alliance enables both companies to build bridges between the various music markets (physical, digital and live) and to offer the public new services, thereby developing new growth drivers which will ultimately benefit the entire music industry. This major sales partnership in Fnac’s physical and digital networks will accelerate the recruitment of new Deezer customers. The success of this acceleration will allow Fnac to become a Deezer shareholder. Fnac and Deezer are putting in place a commercial network that combines their respective strengths: - Starting from the second half of 2017, Fnac and Darty customers will benefit from access offers to Deezer services, particularly when it comes to buying audio and music products (CDs, speakers, headphones, etc.) or membership programs. - Thanks to Deezer, Fnac customers will now be able to listen to music before buying it, not only at Fnac.com but also in stores. -

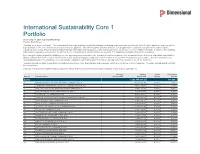

International Sustainability Core 1 Portfolio As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings Are Subject to Change

International Sustainability Core 1 Portfolio As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: State Street Holdings are subject to change. The information below represents the portfolio's holdings (excluding cash and cash equivalents) as of the date indicated, and may not be representative of the current or future investments of the portfolio. The information below should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any security. This listing of portfolio holdings is for informational purposes only and should not be deemed a recommendation to buy the securities. The holdings information below does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. The holdings information has not been audited. By viewing this listing of portfolio holdings, you are agreeing to not redistribute the information and to not misuse this information to the detriment of portfolio shareholders. Misuse of this information includes, but is not limited to, (i) purchasing or selling any securities listed in the portfolio holdings solely in reliance upon this information; (ii) trading against any of the portfolios or (iii) knowingly engaging in any trading practices that are damaging to Dimensional or one of the portfolios. Investors should consider the portfolio's investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses, which are contained in the Prospectus. Investors should read it carefully before investing. Your use of this website signifies that you agree to follow and be bound by the terms and conditions -

Chart Show Across Europe

EWS Moving Chairs NRJpreparesto launch FRANCE WEA Music France has announced a spate of appointments, all made over the past two months. Former Epic chart showacrossEurope product manager local & international, Franck Veron, has arrived at WEA as by Renzi Bouton Pfalz. The tracks for each show arestations associated with the group. promotion director, and another Epic selected by NRJ's head office in Paris According to Sabot, this shows the product manager, Stephane PARIS -French CHR broadcasterafter an analysis of the weeklyvalidity of NRJ's philosophy that sta- Charbonnier, has joined Veron at NRJ islaunchinga new pan-playlists of all NRJ associated sta-tions targeting the same audience WEA as head of marketing/sales. European chart show based on the tions in Europe. group with a similar format in differ- Alexandre Levy, former head of mar- station's most played songs on all its "The Euro Hot 30 reflects the music ent European territories can operate ketingforEMI's Odeon Label CHR stations across Europe. programmingofNRJ'sstations a very similar music program- Group, has joined WEA as head of The Euro Hot 30 show premiered throughout Europe," says Sabot. "It isming. "What makes the dif- artist marketing. Finally, Alain Figari on May 3 on the six German Energya synthesis of what is played on ourference," he says, "is the and Franck Tuil were appointed sales stations associated with the NRJ stations. We are currently fine-tuninglocal content" added to the director and director of sales promo- group. The programme is currentlythe methodology and evaluating theprogramming mix. tion, respectively, on May 5. -

Case No COMP/M.3333 ΠSONY / BMG

EN This text is made available for information purposes only. A summary of this decision is published in all Community languages in the Official Journal of the European Union. Case No COMP/M.3333 – SONY / BMG Only the English text is authentic. REGULATION (EC) No 4064/89 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 8 (2) Date: 03/10/2007 COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 03/X/2007 C(2007) 4507 PUBLIC VERSION COMMISSION DECISION of 03/X/2007 declaring a concentration to be compatible with the common market and the EEA Agreement (Case No COMP/M.3333 – Sony/ BMG) 2 I. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................... 11 II. THE PARTIES.......................................................................................................... 12 III. THE CONCENTRATION ........................................................................................ 12 IV. COMMUNITY DIMENSION .................................................................................. 12 V. RELEVANT MARKETS.......................................................................................... 13 A. RELEVANT PRODUCT MARKET .............................................................. 13 1. PHYSICAL RECORDED MUSIC ................................................... 13 2. RECORDED MUSIC IN DIGITAL FORMATS ............................. 14 a) Introduction ....................................................................... 14 b) The wholesale market for licensing of digital music ........ 15 c) The digital -

Music Industries Take Issue with Government

I R U N D T H E W O R L D nternationalT H E L A T E S T N E W S A N D V E W S F R O M A O Music Industries Take Issue With Government FNAC Signals Int'I Expansion Report Criticizes Japanese Price System Oz Parallel -Import Relaxation Blocked BY STEVE McCLURE concluded that there is not enough BY CHRISTIE ELIEZER with the music industry that chang- Via Paris Store reason for keeping the system ing the copyright act would destroy TOKYO -The Japanese record intact," the Recording Industry SYDNEY-The music industry here the independent sector and make BY REMI BOUTON industry is describing as "regret- Assn. of Japan (RIAJ) says in a has stepped up its campaigning the industry vulnerably to piracy. table" a government report critical of statement, noting that the subcom- after winning a temporary reprieve The industry has argued that drop- PARIS -The opening of a new flag- the country's controversial resale mittee stopped short of recommend- from the federal government's plans ping the 22% sales Lax on records, ship store on the Champs-Elysées price maintenance system, the sys- ing its outright abolition. to relax parallel import restrictions. which raises $120 million Australian here marks the kickoff of an ambi- tem that enables producers of copy- "We are determined to make fur- The Copyright Amendment Bill ($79 million) annually, would have tious international expansion plan right- related ther efforts to appeal for the need to No. 2 passed through the House of the desired effect.