Major Developments Should Have Dedicated Public Transport Routes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property Guide – Welcome to Our Home!

PROPERTY GUIDE – WELCOME TO OUR HOME! We hope you enjoy your stay here and enjoy what London has to offer. Keys/Access to the property 1 key for the building, 2 keys for flat door. First unlock the bottom lock with the big key, then the top lock with the smaller key. Please ensure you always shut all windows and lock the bottom lock on your way out. PLEASE BE CAREFUL NOT TO LOSE THE KEYS OR LOCK THEM IN THE PROPERTY. Particular requests and information about the Bright and spacious duplex apartment situated in a quiet property green area near a vibrant high street with a variety of shops, an abundance of cafes and restaurants with cuisines from all over the world, whilst only a short tube journey away from central London. Two double bedrooms, 2 x bathrooms (1 en-suite), separate guest WC. Lounge room with a 55 x inch smart TV with Netflix and high speed internet connection, separate kitchen (with a Nutribullet blender and a Nespresso coffee machine), dining room overlooking a well maintained shared garden, off street parking in a private driveway. A short walk from Hampstead Heath and Golders Hill park which houses a butterfly house, a zoo, a deer enclosure, a number of ponds and tennis courts. Basic House Rules No Smoking – No Pets Allowed – No Partying or Loud Noises Keep the place clean and tidy – no dirty dishes left over please Fee for lost key from £50 and £100 for smoking WIFI Network Name VM1655733 Password 8gdnthqDvwzx Where is the modem kept Behind the TV in the lounge room How the heating & hot water Central heating or other? Central heating system works How the TV system works Remote controlled, the home entertainment system manual is on (if applicable) the TV stand. -

Chipping Barnet Constituency Insight and Evidence Review

Chipping Barnet Constituency Insight and Evidence Review 1 Contents 1 Introduction....................................................................................................................................3 2 Overview of Findings ......................................................................................................................3 2.1 Challenges of an ageing & isolated population ......................................................................3 2.2 Pockets of relative deprivation...............................................................................................4 2.3 Obesity and Participation in Sport..........................................................................................4 3 Recommended Areas of Focus .......................................................................................................5 4 Summary of Key Facts.....................................................................................................................6 4.1 Population ..............................................................................................................................6 4.2 Employment ...........................................................................................................................6 4.3 Deprivation .............................................................................................................................6 4.4 Health .....................................................................................................................................7 -

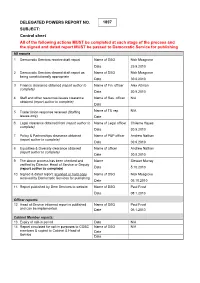

Delegated Powers Report No

DELEGATED POWERS REPORT NO. 1897 SUBJECT: Control sheet All of the following actions MUST be completed at each stage of the process and the signed and dated report MUST be passed to Democratic Service for publishing All reports 1. Democratic Services receive draft report Name of DSO Nick Musgrove Date 29.9.2010 2. Democratic Services cleared draft report as Name of DSO Nick Musgrove being constitutionally appropriate Date 30.9.2010 3. Finance clearance obtained (report author to Name of Fin. officer Alex Altman complete) Date 30.9.2010 4. Staff and other resources issues clearance Name of Res. officer N/A obtained (report author to complete) Date 5. Trade Union response received (Staffing Name of TU rep. N/A issues only) Date 6. Legal clearance obtained from (report author to Name of Legal officer Chileme Hayes complete) Date 30.9.2010 7. Policy & Partnerships clearance obtained Name of P&P officer Andrew Nathan (report author to complete) Date 30.9.2010 8. Equalities & Diversity clearance obtained Name of officer Andrew Nathan (report author to complete) Date 30.9.2010 9. The above process has been checked and Name Stewart Murray verified by Director, Head of Service or Deputy (report author to complete) Date 5.10.2010 10. Signed & dated report, scanned or hard copy Name of DSO Nick Musgrove received by Democratic Services for publishing Date 05.10.2010 11. Report published by Dem Services to website Name of DSO Paul Frost Date 08.1.2013 Officer reports: 12. Head of Service informed report is published Name of DSO Paul Frost and can be implemented. -

Hendon Constituency Insight and Evidence Review

Hendon Constituency Insight and Evidence Review 1 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 2 Overview of Findings ....................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Deprivation and Employment ................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Increasing Diversity & Community Cohesion .......................................................................... 4 2.3 Health and Participation in Sport ............................................................................................ 4 3 Recommended areas of focus ...................................................................................................... 5 • Deprivation and Employment ......................................................................................................... 5 • Increasing Diversity & Community Cohesion .................................................................................. 5 • Health and Participation in Sport .................................................................................................... 5 4 Summary of Key Facts ..................................................................................................................... 6 4.1 Population .............................................................................................................................. -

London Borough of Barnet Election Results 1964-2010

London Borough of Barnet Election Results 1964-2010 Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher The Elections Centre Plymouth University The information contained in this report has been obtained from a number of sources. Election results from the immediate post-reorganisation period were painstakingly collected by Alan Willis largely, although not exclusively, from local newspaper reports. From the mid- 1980s onwards the results have been obtained from each local authority by the Elections Centre. The data are stored in a database designed by Lawrence Ware and maintained by Brian Cheal and others at Plymouth University. Despite our best efforts some information remains elusive whilst we accept that some errors are likely to remain. Notice of any mistakes should be sent to [email protected]. The results sequence can be kept up to date by purchasing copies of the annual Local Elections Handbook, details of which can be obtained by contacting the email address above. Front cover: the graph shows the distribution of percentage vote shares over the period covered by the results. The lines reflect the colours traditionally used by the three main parties. The grey line is the share obtained by Independent candidates while the purple line groups together the vote shares for all other parties. Rear cover: the top graph shows the percentage share of council seats for the main parties as well as those won by Independents and other parties. The lines take account of any by- election changes (but not those resulting from elected councillors switching party allegiance) as well as the transfers of seats during the main round of local election. -

Brent Valley & Barnet Plateau Area Framework All London Green Grid

All Brent Valley & Barnet Plateau London Area Framework Green Grid 11 DRAFT Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 9 Area Description 10 Strategic Context 11 Vision 14 Objectives 16 Opportunities 20 Project Identification 22 Clusters 24 Projects Map 28 Rolling Projects List 34 Phase One Early Delivery 36 Project Details 48 Forward Strategy 50 Gap Analysis 51 Recommendations 52 Appendices 54 Baseline Description 56 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GGA11 Links 58 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA11 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www.london.gov.uk/publication/all-london- green-grid-spg . Cover Image: View across Silver Jubilee Park to the Brent Reservoir Foreword 1 Introduction – All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology Introduction Area Frameworks Partnership - Working The various and unique landscapes of London are Area Frameworks help to support the delivery of Strong and open working relationships with many recognised as an asset that can reinforce character, the All London Green Grid objectives. -

Brent Cross Cricklewood in the London Borough of Barnet

planning report PDU/1483/02 12 March 2010 Brent Cross Cricklewood in the London Borough of Barnet planning application no. C/17559/08 Strategic planning application stage II referral (old powers) Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2000 The proposal Outline application for comprehensive mixed use redevelopment of the Brent Cross Cricklewood regeneration area comprising residential, town centre uses including retail, leisure, hotel and conference facilities, offices, industrial and other business uses, rail-based freight facilities, waste handling facility, petrol filling station, community, health and education facilities, private hospital, open space and public realm, landscaping and recreation facilities, new rail and bus stations, vehicular and pedestrian bridges, underground and multi-storey car parking, works to the River Brent and Clitterhouse Stream and associated infrastructure, demolition and alterations of existing building structures, electricity generation stations, relocated electricity substation, free standing or building mounted wind turbines, alterations to existing railway infrastructure including Cricklewood railway track and station and Brent Cross London Underground station, creation of new strategic accesses and internal road layout, at grade or underground conveyor from waste handling facility to combined heat and power plant, infrastructure and associated facilities together with any required temporary works or structures and associated utilities/services required by the development. The applicant The applicants are Hammerson, Standard Life Investments and Brookfield Europe (“the Brent Cross Development Partners”), and the architect is Allies & Morrison Architects. Strategic issues Outstanding issues relating to retail, affordable housing, urban design and inclusive access, transport, waste, energy, noise, phasing and infrastructure triggers have been addressed. -

Air Quality in Barnet a Guide for Public Health

AIR QUALITY IN BARNET A GUIDE FOR PUBLIC HEALTH PROFESSIONALS Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Barnet COPYRIGHT Greater London Authority September 2013 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4531 Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Barnet CONTENTS Description Page How to use this document 1 1 Introduction 2 2 Air Pollution 3 2.1 External air pollution 3 2.2 Internal air pollution 6 3 Air Quality in LB Barnet 8 4 Air quality impacts on health 12 4.1 Premature deaths 12 4.2 Vulnerable groups 13 4.3 Air pollution and deprivation 14 4.4 The Public Health Outcomes Framework 15 5 Health impacts in LB Barnet 17 6 Co-benefits of improving air quality in London 20 6.1 Maximising the health benefits from improving air quality 20 6.2 Cost of the impact of Air Pollution 21 7 Policy and legal framework for improving air quality 23 7.1 EU Directive 23 7.2 UK air quality policy 23 7.3 Regional strategies 24 7.4 Local Authority responsibilities 26 8 Taking action 27 8.1 Actions taken by the Mayor 27 8.2 Borough level action 28 8.3 Individual action 30 9 Next steps 32 10 References 33 11 Glossary 35 12 Appendices 40 Appendix 1 – Annual mean concentration of pollutants 40 Appendix 2 – National air quality objectives 41 Appendix 3 – Actions for Londoners to mitigate and adapt to air pollution 43 Air Quality Information for Public Health Professionals – London Borough of Barnet HOW TO USE THIS DOCUMENT Air quality is an important Public Health issue in London, it contributes to shortening the life expectancy of all Londoners, disproportionately impacting on the most vulnerable. -

North London Development Opportunity

North London Development Opportunity St John’s Church Hall, Friern Barnet Lane, Whetstone, London N20 0LP For sale freehold For indicative purposes only. Image date October 2015. ■ Development opportunity in the London Borough of Barnet approximately 600 metres from Totteridge & Whetstone London Underground Station. ■ The Property comprises a single storey Church Hall (Use Class D1), which extends to approximately 177 sq m (1,905 sq ft), and associated car parking. ■ Site extending to approximately 0.11 hectares (0.28 acres). ■ Potential for redevelopment for other uses, including residential, subject to the necessary consents. ■ For sale freehold. savills.co.uk Location The site is located in Whetstone, in the London Borough of Barnet. Whetstone is an affluent suburb, approximately 10km (6 miles) to the north of Central London. The property fronts Friern Barnet Lane, approximately 25 metres from the junction with High Road Finchley (A1000). To the immediate north west is a former police station that is currently being redeveloped into a school. There are residential properties to the east and north of the property. A wide range of local retailers are based along High Road (A1000) nearby with further extensive amenities south towards Tally Ho corner. There are numerous green open spaces in the area, including Friary Park and Bethune Park along with North Middlesex Golf Club 200 metres to the south and South Herts Golf Club 1.3km (0.8 miles) to the north west. Totteridge & Whetstone London Underground Station is approximately 600 metres to the north west and provides access to the Northern Line and direct services to the City of London (Bank 34 minutes) and the West End (Leicester Square 29 minutes). -

Sep 19 Deputy Chief Executive – Cath Shaw

Chief Officer List of Decisions: April 19 – Sep 19 Deputy Chief Executive – Cath Shaw TITLE / DECISION DATE OF DECISION REASON DECISION TAKER Dollis Junior 1.4.19 Chris Smith - To approve the granting of a Tenancy at Will pending the transfer of land as a result of the School, Pursley Asst Director, Amalgamation of Dollis Junior School and Dollis Infant School. Road, Estates Mill Hill, NW7 2BU Tenancy at will New CBAT lease 5.4.19 Chris Smith - Approval for a new CBAT lease for Hendon Rugby Club, Greenlands Lane, NW4 for Hendon Rugby Asst Director, Club, Greenlands Under the Community Asset Strategy (CAS), we are providing subsidy as calculated by the Lane, NW4 Estates Community Benefit Assessment Tool (CBAT) to community groups. This group will receive 90% subsidy on their open market rental value of £9,450pa, meaning the rent payable will be £945. This is a 60 contracted out lease, with a mutual break at year 20 Physic Well 12.4.19 Chris Smith - The London Borough of Barnet (The Corporation) will lease the above property to Barnet Museum Asst Director, for use as an historic attraction. Well Approach, Barnet, EN5 3DY Estates The agreed Heads of Terms are attached but the salient points are: Term 50 years Rent Peppercorn Security of tenure Yes within the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 security of tenure provisions Rent Review Not Applicable Brent Cross 15.4.19 Cath Shaw This report requests approval to appoint Conway Aecom through the London Highways Alliance Cricklewood Contract (LoHAC) Framework to undertake works related to the delivery of the Southern Junctions Regeneration: (Cricklewood Broadway/Cricklewood Lane/Chichele Road and Cricklewood Lane/Claremont Core Critical Road/Lichfield Road) improvement works as part of the Brent Cross Cricklewood scheme. -

Growth and Regeneration Programme

Growth and Regeneration Programme Appendix 1 | Annual Regeneration Report November 2012 – March 2014 update April 2014 – March 2015 forward plan Contents PROGRAMME OVERVIEW ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Working with local people through transition ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Key Facts ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Regeneration Strategy ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Corporate objectives .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Regeneration & the Local Plan .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Priority Order List Mayor's Question Time Wednesday 18 December 2013

Agenda Item 5 PriorityOrderList Mayor'sQuestionTime Wednesday18December2013 ReportNo:5 Subject: QuestionstotheMayor Reportof: ExecutiveDirectorofSecretariat QuestionsnotaskedduringMayor’sQuestionTimewillbegivenawritten responsebyMonday23December2013. "Fitforthefuture"programme QuestionNo:2013/4865 ValerieShawcross Isthe"fitforthefuture"programmeofstaffingcutstostationsaffectedbythisyear'sfare decision? Olympic TransportLegacy QuestionNo:2013/4711 RichardTracey WhatprogresshasbeenmadeinmakingtheJavelintrainservice,whichwassosuccessful duringtheOlympics,availabletoLondonersusingtravelcardsandOystercards,as recommendedbytherecentHouseofLordsSelectCommitteereport? Tackling excesswinterdeathsandfuelpoverty QuestionNo:2013/4637 JennyJones WhatimpactwilltheGovernment'sdecisiontoscalebacktheEnergyCompanyObligation haveonyourplanstotackleLondon'senergyinefficientandhardtotreathomes? Making CyclingSaferinLondon QuestionNo:2013/5263 CarolinePidgeon WhatactionareyounowtakingtomakecyclingsaferinLondon? Page 1 Juniorneighbourhoodwardens' scheme QuestionNo:2013/4709 RogerEvans SouthamptonCouncilhasajuniorneighbourhoodwardensscheme,wherebyyoungpeople agedseventotwelvehelplookafterthehousingestatesonwhichtheylive.Wouldyou considerpilotingasimilarschemetoencourageyoungpeopletoshareintheresponsibility fortheirneighbourhoods,throughactivitiessuchaslitter-picking,gardeningandpainting? Risingfuelbills QuestionNo:2013/4866 MuradQureshi WhatwouldLondonersbenefitfrommost,cutstogreenleviesthatfundthewaronfuel povertyora20-monthenergypricefreeze?