Steller's Jay (Cyanocitta Stelleri)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyanocitta Stelleri)

MOBBING BEHAVIOR IN WILD STELLER’S JAYS (CYANOCITTA STELLERI) By Kelly Anne Commons A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Natural Resources: Wildlife Committee Membership Dr. Jeffrey M. Black, Committee Chair Dr. Barbara Clucas, Committee Member Dr. Micaela Szykman Gunther, Committee Member Dr. Alison O’Dowd, Graduate Coordinator December 2017 ABSTRACT MOBBING BEHAVIOR IN WILD STELLER’S JAYS (CYANOCITTA STELLERI) Kelly Anne Commons Mobbing is a widespread anti-predator behavior with multifaceted functions. Mobbing behavior has been found to differ with respect to many individual, group, and encounter level factors. To better understand the factors that influence mobbing behavior in wild Steller’s jays (Cyanocitta stelleri), I induced mobbing behavior using 3 predator mounts: a great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), common raven (Corvus corax), and sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter cooperii). I observed 90 responses to mock predators by 33 color-marked individuals and found that jays varied in their attendance at mobbing trials, their alarm calling behavior, and in their close approaches toward the predator mounts. In general, younger, larger jays, that had low prior site use and did not own the territory they were on, attended mobbing trials for less time and participated in mobbing less often, but closely approached the predator more often and for more time than older, smaller jays, that had high prior site use and owned the territory they were on. By understanding the factors that affect variation in Steller’s jay mobbing behavior, we can begin to study how this variation might relate to the function of mobbing in this species. -

Walker Marzluff 2017 Recreation Changes Lanscape Use of Corvids

Recreation changes the use of a wild landscape by corvids Author(s): Lauren E. Walker and John M. Marzluff Source: The Condor, 117(2):262-283. Published By: Cooper Ornithological Society https://doi.org/10.1650/CONDOR-14-169.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1650/CONDOR-14-169.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Volume 117, 2015, pp. 262–283 DOI: 10.1650/CONDOR-14-169.1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Recreation changes the use of a wild landscape by corvids Lauren E. Walker* and John M. Marzluff College of the Environment, School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA * Corresponding author: [email protected] Submitted October 24, 2014; Accepted February 13, 2015; Published May 6, 2015 ABSTRACT As urban areas have grown in population, use of nearby natural areas for outdoor recreation has also increased, potentially influencing bird distribution in landscapes managed for conservation. -

A Fossil Scrub-Jay Supports a Recent Systematic Decision

THE CONDOR A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY Volume 98 Number 4 November 1996 .L The Condor 98~575-680 * +A. 0 The Cooper Omithological Society 1996 g ’ b.1 ;,. ’ ’ “I\), / *rs‘ A FOSSIL SCRUB-JAY SUPPORTS A”kECENT ’ js.< SYSTEMATIC DECISION’ . :. ” , ., f .. STEVEN D. EMSLIE : +, “, ., ! ’ Department of Sciences,Western State College,Gunnison, CO 81231, ._ e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Nine fossil premaxillae and mandibles of the Florida Scrub-Jay(Aphelocoma coerulescens)are reported from a late Pliocene sinkhole deposit at Inglis 1A, Citrus County, Florida. Vertebrate biochronologyplaces the site within the latestPliocene (2.0 to 1.6 million yearsago, Ma) and more specificallyat 2.0 l-l .87 Ma. The fossilsare similar in morphology to living Florida Scrub-Jaysin showing a relatively shorter and broader bill compared to western species,a presumed derived characterfor the Florida species.The recent elevation of the Florida Scrub-Jayto speciesrank is supported by these fossils by documenting the antiquity of the speciesand its distinct bill morphology in Florida. Key words: Florida; Scrub-Jay;fossil; late Pliocene. INTRODUCTION represent the earliest fossil occurrenceof the ge- nus Aphelocomaand provide additional support Recently, the Florida Scrub-Jay (Aphelocoma for the recognition ofA. coerulescensas a distinct, coerulescens) has been elevated to speciesrank endemic specieswith a long fossil history in Flor- with the Island Scrub-Jay(A. insularis) from Santa ida. This record also supports the hypothesis of Cruz Island, California, and the Western Scrub- Pitelka (195 1) that living speciesof Aphefocoma Jay (A. californica) in the western U. S. and Mex- arose in the Pliocene. ico (AOU 1995). -

Reconstructing the Geographic Origin of the New World Jays

Neotropical Biodiversity ISSN: (Print) 2376-6808 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tneo20 Reconstructing the geographic origin of the New World jays Sumudu W. Fernando, A. Townsend Peterson & Shou-Hsien Li To cite this article: Sumudu W. Fernando, A. Townsend Peterson & Shou-Hsien Li (2017) Reconstructing the geographic origin of the New World jays, Neotropical Biodiversity, 3:1, 80-92, DOI: 10.1080/23766808.2017.1296751 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/23766808.2017.1296751 © 2017 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 05 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 956 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tneo20 Neotropical Biodiversity, 2017 Vol. 3, No. 1, 80–92, https://doi.org/10.1080/23766808.2017.1296751 Reconstructing the geographic origin of the New World jays Sumudu W. Fernandoa* , A. Townsend Petersona and Shou-Hsien Lib aBiodiversity Institute and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA; bDepartment of Life Science, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan (Received 23 August 2016; accepted 15 February 2017) We conducted a biogeographic analysis based on a dense phylogenetic hypothesis for the early branches of corvids, to assess geographic origin of the New World jay (NWJ) clade. We produced a multilocus phylogeny from sequences of three nuclear introns and three mitochondrial genes and included at least one species from each NWJ genus and 29 species representing the rest of the five corvid subfamilies in the analysis. -

The Vocal Behavior of the American Crow, Corvus Brachyrhynchos

THE VOCAL BEHAVIOR OF THE AMERICAN CROW, CORVUS BRACHYRHYNCHOS THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Sciences in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robin Tarter, B.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Masters Examination Committee Approved by Dr. Douglas Nelson, Advisor Dr. Mitch Masters _________________________________ Dr. Jill Soha Advisor Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology Graduate Program ABSTRACT The objective of this study was to provide an overview of the vocal behavior of the American crow, Corvus brachyrhynchos, and to thereby address questions about the evolutionary significance of crow behavior. I recorded the calls of 71 birds of known sex and age in a family context. Sorting calls by their acoustic characteristics and behavioral contexts, I identified and hypothesized functions for 7 adult and 2 juvenile call types, and in several cases found preferential use of a call type by birds of a particular sex or breeding status. My findings enrich our understanding of crow social behavior. I found that helpers and breeders played different roles in foraging and in protecting family territories from other crows and from predators. My findings may also be useful for human management of crow populations, particularly dispersal attempts using playbacks of crows’ own vocalizations. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Kevin McGowan of Cornell, Dr. Anne Clark of Binghamton University, and Binghamton graduate student Rebecca Heiss for allowing me to work with their study animals. McGowan, Clark and Heiss shared their data with me, along with huge amounts of information and insight about crow behavior. -

Home Range and Habitat Use of Breeding Common Ravens (Corvus

HOME RANGE AND HABITAT USE OF BREEDING COMMON RAVENS IN REDWOOD NATIONAL AND STATE PARKS by Amy Leigh Scarpignato A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Science In Natural Resources: Wildlife August, 2011 ABSTRACT Home range and habitat use of breeding Common Ravens in Redwood National and State Parks Amy Scarpignato Very little is known about home range and habitat use of breeding Common Ravens (Corvus corax) in Redwood National and State Parks (RNSP) despite their identification as nest predators of the Marbled Murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus). I used radio telemetry to examine home range, habitat use, and foraging behavior of breeding Common Ravens in RNSP during 2009 (n = 3) and 2010 (n = 8). I estimated home range and core-use area size, calculated home range overlap between adjacent ravens, and quantified site fidelity by calculating overlap between years for the same individuals. I used Resource Utilization Functions (RUFs) to examine raven resource use within the home range. Average home range size of ravens in RNSP was 182.5 ha (range 82-381 ha) and average core-use area was 31.4 ha (range 5-71 ha). The most supported habitat use models were the global and human models followed by the old-growth model. All beta coefficients in models of individual birds differed from zero suggesting that the variables in the models had a strong influence on home range use. Home range use of individual ravens was generally higher near roads (n = 6), old-growth edge (n = 7), bare ground (n = 6), and in mixed hardwood (n = 5) and prairie habitats (n = 5). -

Observations of Scrub Jays Cleaning Ectoparasites from Black-Tailed Deer

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 145 includingone inside a nestcavity. Six other islandsshowed penetrated in the present study, however, suggeststhat no indication of abnormally low nestingsuccess, and were ermine are quite capable of reaching coastal islands in probably not visited by ermine. years when their populations are high, and that such in- The major effects of ermine on guillemot breeding ap- vasionsmay be more frequent than the paucity of records pearedto be discouragementof egg-layingand a reduction suggests. of hatching successdue to nest abandonment. Many cav- ities on Black, Yellow, and Green islands which were oc- I thank W. Cairns, V. Friesen and H. Kaiser for field cupied in previous years were not used in 1983. Eggslaid assistance,and A. J. Gaston, M. B. Fenton and P. Ewins on islands where ermine presencewas confirmed or sug- for commenting on the manuscript. This study was sup- gestedwere often displacedfrom the nest cup and lacked ported by the Canadian Department of Supply and Ser- the shiny appearancewhich is normal for regularly incu- vices and the Canadian Wildlife Service. bated eggs(pers. observ.). Guillemots may have been re- LITERATURE CITED luctant to enter their nests if they had seen an ermine in the colony, which would explain the reductionin both egg- BANFIELD,A. W. F. 1974. The mammals of Canada. laying and hatching. Univ. of Toronto Press. Ermine visited islands as far as 1.6 km from the main- BIANIU,V. V. 1967. Gulls, shorebirdsand alcids of Kan- land (Pitsulak City), and may have reached Kingituayu dalaksha Bay. Israel Program for Scientific Transla- Island as well (2.2 km). -

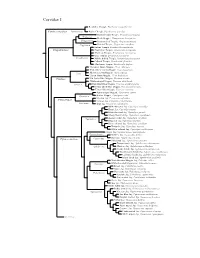

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Cyanocitta Cristata) in Canada, with Comments on the Genus

Proc. Helminthol. Soc. Wash. 53(2), 1986, pp. 270-276 Pseudaprocta samueli sp. n. (Nematoda: Aproctoidea) from the Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata) in Canada, with Comments on the Genus CHERYL M. BARTLETT' AND ROY C. ANDERSON Department of Zoology, College of Biological Science, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario NIG 2 W1, Canada ABSTRACT: Pseudaprocta samueli sp. n. is described from the thoracic air sac of 1 of 20 blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata (L.)) collected near Guelph, Ontario, Canada and this apparently represents the first report in the literature of Pseudaprocta in the New World. Specimens of Pseudaprocta, unidentifiable to species, from a blue jay in Alabama, U.S.A., had, however, been deposited in the United States National Museum in 1954. Pseudaprocta samueli belongs to that group of species within the genus that have short spicules (<500 jim) and 10-11 pairs of caudal papillae. It is distinguished by the irregular spacing of the cephalic spines and the presence of inflated cuticle in the caudal region of the female. An annotated list of and key to species in Pseudaprocta are given. The identities of many of the species reported in Eurasia require clarification. Aproctoids are oviparous nematode parasites Specimens of Pseudaprocta in the WHO Collabo- of the air sacs and orbital sinuses of birds. Their rating Centre for Filarioidea Collection at the Com- relationship to other superfamilies in the order monwealth Institute of Parasitology (CIP) in St. Al- bans, England, and in the Helminth Collection of the Spirurida is not well understood although an or- United States National Museum (USNM) in Beltsville, igin from Seuratoidea (Ascaridida) has been sug- Maryland, U.S.A., which were borrowed and examined gested (Chabaud, 1974; Bain and Mawson, 1981). -

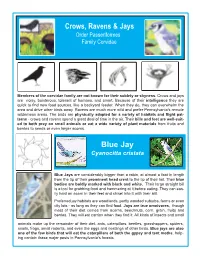

Crows, Ravens, and Jays

Crows, Ravens & Jays Order Passeriformes Family Corvidae Members of the corvidae family are not known for their sublety or shyness. Crows and jays are noisy, boisterous, tolerant of humans, and smart. Because of their intelligence they are quick to find new food sources, like a backyard feeder. When they do, they can overwhelm the area and drive other birds away. Ravens are much more wild and prefer Pennsylvania’s remote wilderness areas. The birds are physically adapted for a variety of habitats and flight pat- terns - crows and ravens spend a great deal of time in the air. Their bills and feet are well-suit- ed to both prey on small animals or eat a wide variety of plant materials from fruits and berries to seeds or even larger acorns. Blue Jay Cyanocitta cristata Blue Jays are considerably bigger than a robin, at almost a foot in length from the tip of their prominent head crest to the tip of their tail. Their blue bodies are boldly marked with black and white. Their large straight bill is a tool for grabbing food and hammering at it before eating. They can eas- ily hold an acorn in their feet and chisel into it with their bill. Preferred jay habitats are woodlands, partly wooded suburbs, farms or even city lots - as long as they can find food. Jays are true omnivores, though most of their diet comes from acorns, beechnuts, corn, grain, fruits and berries. They will eat carrion when they find it. All kinds of insects and small animals make up the remainder of their diet: ants, caterpillars, beetles, grasshoppers, spiders, snails, frogs, small rodents, and even the eggs and nestlings of other birds. -

Blue Jay Cyanocitta Cristata Adult ILLINOIS RANGE

blue jay Cyanocitta cristata Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The blue jay averages 11 to12 inches in length. It is a Class: Aves large bird with blue feathers and a crest. White Order: Passeriformes feather patches are present in the wings and tail. A black line behind the head extends from each side Family: Corvidae to form a black “necklace” on the throat. This bird ILLINOIS STATUS has white or gray feathers underneath. common, native BEHAVIORS The blue jay is a common, permanent resident statewide in Illinois. However, blue jays do migrate within Illinois, moving to southern Illinois from the northern sections of the state in the winter. The nesting season lasts from April through mid-July. The nest is built in a forest, residential area, orchard or other location where trees are present, from five to 50 feet above the ground. Both sexes construct the nest of twigs, bark, leaves, mosses and string and line it with rootlets. Four or five olive, tan or blue- green eggs with dark markings are laid. Both the male and female take turns incubating the eggs over a 17- to 18-day period. One brood is raised per year. This aggressive bird uses its loud calls (“jay,” “jeeah,” adult “queedle, queedle”) to alert others to possible danger. The blue jay can mimic some other birds, too. It may go to roost in mid-afternoon in the winter months. Found in woodlands and residential ILLINOIS RANGE areas, the blue jay eats nuts, particularly acorns, corn, fruits, insects and dead animals. © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

Comments Upon Systematics of Pacific Coast Jays of the Genus

72 THE CONDOR Vol. XXXVI Dove 2, Red-shafted Flicker 2, Marsh Wren 5, Robin 6, Pipit 129+, Shrike 1, Audubon Warbler 5, English Sparrow 17+, Red-winged Blackbird 40+, Meadow- lark 36+, Savannah Sparrow 2, Gambel White-crowned Sparrow S+, Song Spar- row 3, unknown 4 [two of these flew up together from rank grass near where red- wings were going to roost-notes strange to me-1 ventured to guess “bobolinks”!]. Total 15 species, 265+ individuals in one hour. To sum up: In 1923 I listed 124 kinds of birds whose presence one or more times in the below-sea-level portion of Death Valley had been established on good evidence. E. L. Sumner, Jr. (Condor, 31, 1929, p. 127) added the Golden Eagle, an individual of which species was seen by him on December 27, 1928, “perched in a dead tree by Bennett’s Wells.” In the present batch of notes there are added to the preceding records, six kinds, namely, Anthony Green Heron, Greater Yellow-legs, Western Horned Owl, Woodhouse Jay, Arizona Verdin, and Thick-billed Red- winged Blackbird. The total list of birds now known from the floor of Death Valley thus numbers 131. Mupeum of Vertebrate Zoology, Berkeley, California, Ncvembh 26, 1933. COMMENTS UPON SYSTEMATICS ,OF PACIFIC COAST JAYS OF THE GENUS CYANOCITTA WITH ONE ILLUSTRATION By JAMES STEVENSON During my study of the crested jays (Cyanocitta stelleri) carried on through the past two years, several special problems have arisen concerning the distribution of Pacific coast races. The descriptions of new forms from Oregon by Oberholser in 1932 have, in particular, stimulated my close attention to the crested (Steller) javs of the northwestern United States.