Cardiff and Miller's Road Trip (2004): Between Archive and Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

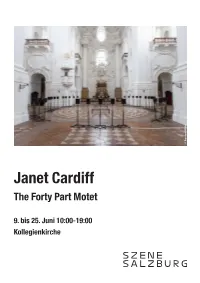

Janet Cardiff

© Bernhard Müller Janet Cardiff The Forty Part Motet 9. bis 25. Juni 10:00-19:00 Kollegienkirche Janet Cardiff The Forty Part Motet Eine Bearbeitung von Spem in Alium Nunquam Habui, 1573 von Thomas Tallis Die kanadische Künstlerin Janet Cardiff hat Die in British Columbia lebende Janet Forty Part Motet wurde ursprünglich produziert mit ihrem international gefeierten Projekt Cardiff entwickelt, meist zusammen mit von Field Art Projects . The Forty Part Motet eine der emotionals- George Bures Miller, seit Jahren Installatio- In Kooperation mit: Arts Council of England, Cana- ten und poetischsten Klanginstallation der nen, Audio- und Video-Walks, die regelmä- da House, Salisbury Festival and Salisbury Cathedral letzten Jahre geschaffen. Die Sommersze- ßig mit Preisen ausgezeichnet werden. Ihre Choir, Baltic Gateshead, The New Art Galerie Walsall, ne 2021 bringt dieses berührende Hörerleb- Einzelausstellungen, die zwischen Wien Now Festival Nottingham nis erstmals nach Salzburg und installiert es und Washington zu sehen waren, sind Er- Gesungen von: Salisbury Cathedral Choir im sakralen Raum der Kollegienkirche. lebnisse für alle Sinne. The Forty Part Mo- Aufnahme & Postproduction: SoundMoves Die Grundlage der Arbeit bildet ein 40-stim- tet hat bereits Besucher*innen von der Tate Editiert von: Georges Bures Miller miges Chorstück, das aus vierzig Lautspre- Gallery bis zum MOMA begeistert. Eine Produktion von: Field Art Projects chern, die kreisförmig angeordnet sind, ab- gespielt wird. Janet Cardiff hat die Stimmen „While listening to a concert you are nor- Mit Unterstützung von der Motette Spem in Alium des englischen mally seated in front of the choir, in tradi- Renaissance-Komponisten Thomas Tallis tional audience position. (…) Enabling the aus dem 16. -

Having Experienced Janet Cardiff's Forty Part Motet on Several Different

________ Having experienced Janet Cardiff’s Forty Part Motet on several different occasions, I have developed a strong preference for positioning myself with my back to one of the silent speakers at the beginning of the piece. The piece is composed of forty speakers arranged in eight groups of five, configured as a large oval facing each other in the center of the room, and resting on stands so they are roughly just above eye level. The Motet, as Cardiff referred to it in our conversation, is a reworking of the English composer Thomas Tallis's Spem in Alium (1570), which translates as “Hope in Any Other” and is sung in Latin by a choir of forty voices. The composition is arranged so that the choir, like the speakers, is divided into eight groups of five singers; each group consists of a soprano, tenor, alto, baritone, and bass. The groups alternate singing: first one, than another, sometimes alone, and at a few moments, all together, rising in a crescendo that breaks open the room to a place beyond the physical world. To hear the Motet in its entirety is profound, and there is no preferential way to experience it. Visitors sit or stand in the center, walk around inside or outside the perimeter, close their eyes or watch one another, follow the choirs across the room, or, as I do, pick a speaker and wait. If I have positioned myself as desired, the ethereal voice of a young male soprano, heartbreaking in its clarity, rings out from behind my head into the space and leaves me shattered in its wake. -

Sound and Documentary in Cardiff and Miller's

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: SOUND AND DOCUMENTARY IN CARDIFF AND MILLER’S ‘PANDEMONIUM’ Cecilia T. Wichmann, Master of Arts, 2015 Thesis directed by: Professor Joshua Shannon Department of Art History and Archaeology From 2005 to 2007, Canadian artists Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller automated a live performance of simple robots striking furniture detritus and pipes in the cells of Eastern State Penitentiary, a Philadelphia prison that once specialized in isolation and silence. Oscillating between referential and abstract sounds, Pandemonium suspended percipients between narrative and noise. So far scholars have investigated only the work’s narrative aspects. This projects examines Cardiff and Miller’s specific use of percussive sounds to position Pandemonium in dialogue with noise music, sound art, and documentary-related practices in contemporary art. Pandemonium’s representational sounds coalesce into a curious kind of concrete documentary that triggered a sense of radical proximity between the percipient’s body and the resonant environment of Eastern State Penitentiary. In doing so, it explored the potential for sensory relations and collectivity in a complex, contemporary world. SOUND AND DOCUMENTARY IN CARDIFF AND MILLER’S ‘PANDEMONIUM’ by Cecilia T. Wichmann Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 Advisory committee: Professor Joshua Shannon, Chair Professor Renée Ater Professor Steven Mansbach © 2015 Cecilia T. Wichmann For Andrew. ii Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the openness and generosity of Sean Kelley, Senior Vice President and Director of Public Programming at Eastern State Penitentiary, who readily shared his records and memories of Pandemonium. -

Canada in Venice an ESSAY by GENEVIEVE FARRELL

Canada In Venice AN ESSAY BY GENEVIEVE FARRELL First held in 1895, La Biennale di Venezia was organized in an effort to of works from its permanent collection by artists who have rebrand the decaying city of Venice. Emphasizing the country’s active represented Canada at the Venice Biennale) the exhibitors have been contemporary art scene, the event aimed to fuel tourism (the city’s predominantly white males hailing from Ontario or Quebec. Of the only remaining industry) while propelling Italian art and artists into the 65 artists who have represented the nation thus far, only 10 have 20th century. Drawing in over 200,000 visitors, the overwhelmingly been women. Rebecca Belmore remains the only female Indigenous popular and commercial success of this exhibition propelled the city artist to represent the nation (2005), and while no woman of color has to establish foreign country pavilions within their “Padiglione Italia” exhibited in the Canadian Pavilion, the choreographer Dana Michel (or “Giardini” / “Central Pavilion”). The Venice Biennale has continued became the first Canadian to win a Silver Lion (life time achievement to grow, to become a much larger event where countries exhibit award) at the Venice Dance Biennale in 2017. While these statistics the best of their nations’ contemporary cultural production. After are not atypical when one looks at the history of Biennale exhibitors surviving two world wars and much political upheaval, the biennale from other participating nations, the information should provoke is now a foundation that not only runs a bi-annual contemporary serious reflection on the historic political and cultural values of art exhibition, but also the Architecture Biennale, the Venice Film western nations. -

A Space Without Memory: Time and the Sublime in the Work of Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-11-2014 12:00 AM A Space Without Memory: Time and the Sublime in the Work of Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller Margherita N. Papadatos The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Professor Joy James The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Art History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Margherita N. Papadatos 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons, Audio Arts and Acoustics Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Other Philosophy Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Papadatos, Margherita N., "A Space Without Memory: Time and the Sublime in the Work of Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2439. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2439 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SPACE WITHOUT MEMORY: TIME AND THE SUBLIME IN THE WORK OF JANET CARDIFF AND GEORGE BURES MILLER (Thesis format: Monograph) by Margherita Papadatos Graduate Program in Visual Arts A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art History The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies -

Janet Cardiff's Portraits of Sounds: Drawing the Auditory

Janet Cardiff’s Portraits of Sounds: Drawing the auditory There are so many sounds in the urban world that it is easy to get overwhelmed and tune them out. Instead, this assignment asks you to focus on the sounds around you, consider how they make you feel, and explore ways of using art to represent them. Materials: Assignment Drawing, Painting, Sound Create a CD or load an iPod with various sound effects (airplanes taking off, gunshots, construction Materials: noise, highway traffic, bird songs, footsteps, music + Brushes clips, etc.). Play the sound effects and encourage the students to create an intuitive response on a + CD or iPod large piece of paper. Encourage them to think about + Clothes the sound and the choice of materials, colors, and textures. Ask them to work both on the floor and on a + Paper desk so that their physical approach varies according + Paint to the sounds they are hearing. Ask them to alternate between working with closed eyes and with their eyes + Pens and pencils open and see how this changes their responses to the sounds. + Sponges After the students have completed their sound portraits, ask the class to compare different responses to the same sound. What are the similarities? Do the sounds seem to have evoked similar reactions (e.g., short lines, bright colors, patterns)? Discuss the idea of aural language and ask the students to consider whether it can be translated visually. Did using sound as inspiration make them think differently about the images they created? Artist Biography: Janet Cardiff Born in Brussels, Ontario, Canada Currently lives and works in Berlin, Germany, and Grindrod, British Columbia, Janet Cardiff recording with Canada binaural head, Jena, 2006 Janet Cardiff is internationally recognized for her immersive multimedia works. -

Janet Cardiff Forty-Part Motet Hall 5 December 2003 - 15 February 2004

JANET CARDIFF FORTY-PART MOTET HALL 5 DECEMBER 2003 - 15 FEBRUARY 2004 The Canadian artist Janet Cardiff is renowned for her works combining sound and image. In Cardiff’s work the experience of space plays an important role. Cardiff fuses physical space and virtual space in her work. Characteristic of Cardiff’s work is also the transformation of the passive viewer into an active participant. Pori Art Museum presents the monumental sound installation by Janet Cardiff Forty Part Motet (2001). Forty Part Motet is a reworking of the Spem in Alium Nunquam Habui (1575) by Thomas Tallis. In the installation forty separately recorded voices are played back through forty speakers. The speakers are placed in the space strategically in eight groups of five as indicated by the Tallis score. Cardiff seeks to render the music in a new way. Normally in a concert the only viewpoint is from the front, in the traditional audience position. Whereas in Cardiff’s installation, the audience can move in the exhibition space and listen to the music from any vantage point they choose. The experience of the piece is generated by the movement in the space and sound becomes an ever-changing construct. Cardiff is interested in how sound may physically construct a space in a sculptural way. Forty Part Motet forms a structural, almost architectural whole. Thomas Tallis (c. 1505 - 1585) was the most influential English composer of his generation. Tallis served as organist to four English monarchs - Henry VIII, Edward VI, Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth - as a gentleman of the Chapel Royal. -

Cardiff & Miller

JANET CARDIFF & GEORGE BURES MILLER Janet Cardiff Born: 1957, Brussels, Ontario, Canada. George Bures Miller Born: 1960, Vegreville, Alberta, Canada. Live and work in Berlin, Germany and Grindrod, B.C., Canada. AWARDS AND HONORS DAAD Grant and Residency, Berlin, Germany, 2000. La Biennale di Venezia Special Award, 49th Venice Biennale, 2001. The Benesse Prize, 49th Venice Biennale, 2001. The Gershon Iskowitz Prize, 2003. Käthe Kollwitz Prize, 2011. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS: 2014-2015 ―Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller: The Marionette Maker,‖ Palacio de Cristal, Parque del Retiro, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain ―Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller – Something Strange This Way,‖ ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, Aarhus, Denmark (catalogue) 2014 ―Janet Cardiff: The Forty-Part Motet,‖ 2014 Galway International Arts Festival, Aula Maxima, Galway, Ireland (Cardiff) ―Janet Cardiff: The Forty-Part Motet,‖ High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA (Cardiff) ―Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller: Lost in the Memory Palace,‖ Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, Canada 2013 ―Janet Cardiff: The Forty-Part Motet,‖ Winnipeg Art Gallery, Winnipeg, Canada (Cardiff) ―Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller - The Murder of Crows,‖ Centrum for Konst och Design, Vandalorum, Sweden ―Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller: Lost in the Memory Palace,‖ Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada; Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, La Jolla, CA ―Janet Cardiff: The Forty-Part Motet,‖ Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH (Cardiff) ―The Paradise Institute,‖ -

Janet Cardiff Forty-Part-Motet Brochure

Janet Cardiff: Forty-Part Motet Organized by the National Gallery of Canada at the Surrey Art Gallery January 12 – March 23, 2008 Surrey Art Gallery 13750-88 Avenue Surrey, BC V3W 3L1 (1 block east of King George Highway, in Bear Creek Park) Information: 604-501-5566 www.arts.surrey.bc www.surreytechlab.ca [email protected] Janet Cardiff: Forty-Part Motet, 2001. 40-track audio installation, 14 minutes in duration. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Image courtesy of the Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay About Janet Cardiff Janet Cardiff was born in Brussels, Ontario in 1957 and studied at Queen's University (BFA) and the University of Alberta (MVA). She works in collaboration with her partner George Bures Miller, born 1960, Vegreville, Alberta. Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller currently live and work in Berlin, and Grinrod BC. Cardiff's installations and walking pieces are often audio-based. She has been included in exhibitions such as: Present Tense, Nine Artists in the Nineties, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, NowHere, Louisiana Museum, Denmark, The Museum as Muse, Museum of Modern Art, the Carnegie International '99/00, the Tate Modern Opening Exhibition as well as a project commissioned by Artangel in London. Cardiff represented Canada at the São Paulo Art Biennial in 1998, and at the 6th Istanbul Biennial in 1999 with her partner George Bures Miller. Cardiff and Bures Miller represented Canada the 49th Venice Biennale with "The Paradise Institute" (2001). The artists won La Biennale di Venezia Special Award at Venice, presented to Canadian artists for the first time and the Benesse prize, recognizing artists who try to break new artistic ground with an experimental and pioneering spirit. -

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller March 20

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller March 20 – April 24, 2010 Opening reception: Friday, March 19, 6-8 pm Luhring Augustine is pleased to present an exhibition of new work by the collaborative team Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller. This marks Cardiff and Miller’s third solo exhibition at the gallery. Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller are internationally recognized for their immersive multimedia works. Incorporating dramatic audio tracks into their visually striking installations, the artists create engaging and transcendent multisensory experiences which draw the viewer into ambiguous and unsettling narratives. Their works address grand themes such as time, voyeurism, dreams, and mystery. Providing only fragments of information, the completion of the storylines, images and thoughts are left to be formed in the minds of the individual viewers. Cardiff and Miller’s new installation, The Carnie, combines the artists’ interests in spectacle, narrative, and sculptural sound. A small children’s’ carousel is activated by a start button. It grinds slowly up to speed, while lights and music emanate from the structure and moving shadows are cast onto the walls. Working with Freida Abtan, an electronic composer, Cardiff and Miller deconstruct the musical source and relocate it throughout the structure of the carousel so that the movement of the sound occurs horizontally as well as vertically. The results transform the carnival ride into a layered and evocative encounter. In marked contrast to this large-scale installation, Cardiff and Miller have created a series of works that turns their interest in sound away from the grand spectacle of the amusement park to focus instead on the intimacy of the telephone. -

Okanagan Eyes Okanagan Wise Okanagan-Ise Catalogue of an Exhibition Held at Headbones Gallery, Vernon, British Columbia, Canada from June 24 to Augut 20, 2011

G NA AN W KA I O S E S O E K Y A E N N A A G G A A N N HEADBONES GALLERY - I A S K E O OKANAGAN EYES OKANAGAN WISE OKANAGAN-ISE HEADBONES GALLERY N EYES GA O A K N A A N K A G O A E N S I W - N I S A E G O A K N A June 24 - August 20, 2011 HEADBONES GALLERY Okanagan Eyes Okanagan Wise Okanagan-ise Catalogue of an exhibition held at Headbones Gallery, Vernon, British Columbia, Canada from June 24 to Augut 20, 2011. © 2011 Headbones Gallery 6700 Old Kamloops Road, Vernon, BC V1H 1P8 www.headbonesgallery.com All rights reserved Julie Oakes 1948- ISBN # 978-1-926605-36-4 I. Doug Alcock II. David Alexander III. Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller IV. Glenn Clark V. Leonard Epp VI. John Hall VII. Joice M. Hall VIII. Byron Johnston IX. Jim Kalnin X. Ann Kipling XI. Geert Maas XII. Steve Mennie XIII. David Montpetit XIV. Richard Saurez XV. Carolina Sanchez de Bustamante XVI. Carl St Jean XVII. Bruce Taiji XVIII. Heidi Thompson Curator Julie Oakes Photography Richard Fogarty John Hall, Joice M. Hall, Roman März, Yuri Akuney, Carl St Jean and Heidi Thompson Graphic Design Richard Fogarty Printed by Rich Fog Micro Publishing Publisher Rich Fog Micro Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 copyright act or in writing from Headbones Gallery. -

Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller the Secret Hotel

KUB 05.08 Press release Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller The Secret Hotel November 26, 2005 thru January 15, 2006 Press conference: Karl-Tizian-Platz Postfach 371 Thursday, November 24, 2005, 12.00 noon A-6901 Bregenz Opening: Telefon (+43-55 74) 4 85 94-0 Friday, November 25, 2005, 8.00 p.m. Fax (+43-55 74) 4 85 94-8 E-Mail [email protected] Over the past two decades, Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller (*1957 in Web Brussels, Canada; *1960 in Vegreville, Canada) have developed an www.kunsthaus-bregenz.at impressive series of collaborative pieces, complementing each other’s work in an ingenious way. In their art, they combine image, video, and sound, as well as architectural and sculptural installations that take the viewer on a confusing and fascinating journey. Sound and a special binaural recording and playback technology are key components in their installations, producing a highly sensitive and spatial audio and sensory experience. Their work evokes thoughts and associations that become inextricably interwoven with personal experiences, thus creating a constantly changing new fiction. Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller’s work has been shown at such major international exhibition venues as the PS1, New York, the Musée d’Art Contemporain, Montreal, the Astrop Fearnley Museum, Oslo, the Castello Rivoli in Turin, the Portikus, Frankfurt, and the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London. One of their most well-known works is “The Paradise Institute,” which was their award-winning contribution to the Venice Biennial 2001 and is also being shown in Bregenz.