Using Melucci-S Model of Collective Identity and Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Miscavige Legal Statements: a Study in Perjury, Lies and Misdirection

SPEAKING OUT ABOUT ORGANIZED SCIENTOLOGY ~ The Collected Works of L. H. Brennan ~ Volume 1 The Miscavige Legal Statements: A Study in Perjury, Lies and Misdirection Written by Larry Brennan [Edited & Compiled by Anonymous w/ <3] Originally posted on: Operation Clambake Message board WhyWeProtest.net Activism Forum The Ex-scientologist Forum 2006 - 2009 Page 1 of 76 Table of Contents Preface: The Real Power in Scientology - Miscavige's Lies ...................................................... 3 Introduction to Scientology COB Public Record Analysis....................................................... 12 David Miscavige’s Statement #1 .............................................................................................. 14 David Miscavige’s Statement #2 .............................................................................................. 16 David Miscavige’s Statement #3 .............................................................................................. 20 David Miscavige’s Statement #4 .............................................................................................. 21 David Miscavige’s Statement #5 .............................................................................................. 24 David Miscavige’s Statement #6 .............................................................................................. 27 David Miscavige’s Statement #7 .............................................................................................. 29 David Miscavige’s Statement #8 ............................................................................................. -

Jan. 21St Babbage’S Son IBM Antitrust Calculates Jan

mirror with a $10 cylindrical In his spare time, Starkweather lens. was an avid model railroader. Jan. 21st Babbage’s Son IBM Antitrust Calculates Jan. 21, 1952 The US Department of Justice’s Jan. 21, 1888 (DOJ) filed an antitrust suit Charles Babbage [Dec 26] never against IBM [Feb 14], charging it constructed an Analytical Engine with unlawful restraint of trade, [Dec 23], but his youngest son, and domination of the punch Henry Prevost Babbage (1824- card industry. At the time, IBM 1918), did get around to owned more than 90% of all the building the mill portion (the tabulating machines in the US, arithmetic logic unit) from his and manufactured and sold father’s plans. about 90% of all the cards. On this day, it produced a table Gary Starkweather (2009). A consent decree was issued in of multiples of , complete to 29 Photo by Dcoetzee. CC0. 1956, instructing the company digits, arguably making it the to reduce its share of the market first successful test of a Incredibly, his work generated to a more reasonable 50%. This computer. Over twenty years almost no interest at Webster, was fortuitous timing for Tom later, in April 1910, the results and his manager actually Watson, Jr. [Jan 14] who had just were published in The Monthly threatened to sack anyone who taken over as IBM's CEO; he Notices of the Royal Astronomical 'wasted their time' on the wanted to move the company's Society, followed by errata in the project. focus away from punched card June issue. systems towards computers. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Anonymous Rising

D. C Elliott, Anonymous Rising D.C. Elliott ANONYMOUS RISING On February 10 2008, over 7,000 individuals from across the globe participated in synchronised protests outside their regional branch headquarters of the Church of Scientology. Disguised in the Guy Fawkes masks made popular through the film V For Vendetta, and brandishing placards with baffling, largely indecipherable messages, the protests were considered the first wave of a global protest movement known as Project Chanology, a concept devised by a leaderless, decentralised group calling itself Anonymous. Upon closer inspection by a largely confused, unprepared media, Anonymous turned out to be loosely connected to a group of websites, '- with their primary base of operations . '•'- J. _t•tf- being 4chan.org . The image sharing site Flickr reported 2,000 images uploaded to its servers featuring images taken from the - . protests, causing mayhem through crashes - and software malfunctions, with Flickr or completely unprepared to cope with the ProjectChanology — Sydncy,Australia traffic generated as onlookers scrambled to iO, 2008 their browsers to access the images of what was shaping up to be a unique, bizarre experiment in political resistance and global participation. Subsequent protests were executed throughout 2008, codenamed "The Ides Of March" and "Operation Reconnect" - with video sharing site Youlube being drawn into the battle, hosting a number of press releases issued by members 96 Votume36, 2009 of Anonymous, drawing attention to Scientology's alleged ethical and legal misdeeds. A particularly disturbing release featured a poem narrated over a recording of a child's music box, describing the deaths that have been ascribed to Scientology's policies regarding mental illness and prescription medication, ending with the chilling warning: "Church Of Scientology beware. -

ABSTRACT the Rhetorical Construction of Hacktivism

ABSTRACT The Rhetorical Construction of Hacktivism: Analyzing the Anonymous Care Package Heather Suzanne Woods, M.A. Thesis Chairperson: Leslie A. Hahner, Ph.D. This thesis uncovers the ways in which Anonymous, a non-hierarchical, decentralized online collective, maintains and alters the notion of hacktivism to recruit new participants and alter public perception. I employ a critical rhetorical lens to an Anonymous-produced and –disseminated artifact, the Anonymous Care Package, a collection of digital how-to files. After situating Anonymous within the broader narrative of hacking and activism, this thesis demonstrates how the Care Package can be used to constitute a hacktivist identity. Further, by extending hacktivism from its purely technological roots to a larger audience, the Anonymous Care Package lowers the barrier for participation and invites action on behalf of would-be members. Together, the contents of the Care Package help constitute an identity for Anonymous hacktivists who are then encouraged to take action as cyberactivists. The Rhetorical Construction of Hacktivism: Analyzing the Anonymous Care Package by Heather Suzanne Woods, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of Communication David W. Schlueter, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee Leslie A. Hahner, Ph.D., Chairperson Martin J. Medhurst, Ph.D. James M. SoRelle, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2013 J. Larry Lyon, Ph.D., Dean Page bearing signatures is kept on file in the Graduate School Copyright © 2013 by Heather Suzanne Woods All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................ -

Why “Hacktivism” Can and Should Influence Cybersecurity Reform

INVESTING IN A CENTRALIZED CYBERSECURITY INFRASTRUCTURE: WHY “HACKTIVISM” CAN AND SHOULD INFLUENCE CYBERSECURITY REFORM Brian B. Kelly INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1664 I. CYBERCRIME, HACKTIVISM, AND THE LAW ......................... 1671 A. The Current State of Cybercrime ............................................... 1671 B. Defining Hacktivism and Anonymous’s Place Within the Movement .................................................................................. 1676 1. Hacking and Hacktivism ..................................................... 1676 2. Anonymous ......................................................................... 1678 C. Current Cybersecurity Law ....................................................... 1683 1. Federal Statutes ................................................................... 1683 2. National Defense Systems ................................................... 1684 3. State Monitoring Systems .................................................... 1685 4. International Coalitions ....................................................... 1686 II. CURRENT REFORM PROPOSALS ............................................... 1687 A. Obama Proposal ........................................................................ 1687 B. Republican Task Force Proposal .............................................. 1689 III. THE CYBERSECURITY REFORM SOLUTION ........................... 1692 A. Similarities in the Reform Models ............................................ -

Church of Scientology Judicial Review

HO.ME OFFICE - Feu 03 0001/0029/003/ -.." RELATED PAPERS FILE BEGINS: __ __ ENDS: FILE TITLE: - : POLICY (REVIEW AFTER 25 YEARS) CULTS I NEW RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS s: . '- CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY JUDICIAL REVIEW - SEND TO I DATE - SEND TO DATE SEND TO -- DATE . ZO,3 -. , - -- 0 0 - -- 0 . 0 - " -0 . 0 0 -- 0 HOF000647241 ese 8111 .. .. --- _ .. - - - -- - -- - _. , - AnnexA Press Office to take Subject: Judicial Review Case: Recognition of Scientology as a religion in prison Tuesday 21 October - permissions hearing for a judicial review on HRA grounds of Prison Service policy not to recognise Scientology as a religion for the purpose of facilitating religious ministry in prisons. Background Prisoner Roger Charles Heaton and the Church of Scientology have made an application for jUdicial review of this policy. Unes to take The applicants, having seen our witness statement and outline argument, have offered to withdraw their case, with no order as to costs. This means that the non-recognition policy being followed by prison service is reasonable .and secure. It has been our long-standing policy to withhold recognition of scientology as a religion. However, in order to meet the needs of individual prisoners, the Prison Service allows any prisoner registered as a Scientologist to have access to a representative of the Church of Scientology if he wishes to receive its ministry. This is the approach which was followed in the case of Mr Heaton. The Home Office considers that its policy respects the rights of Mr Heaton under the ECHR and is reasonable in view of concerns of which the department is aware about some of the practices of the Church. -

Anonymous Operations and Techniques

Anonymous Operations and Techniques The story of Anonymous: How to go from ultra-coordinated motherfuckery to uncoordinated dumbfuckery in less than 3 years Speaker Introduction •Flanvel •Viz The Beginning • 2003-2006 • 4chan 2006-2007 • Habbo raids • July 6th 2006 • THE POOL IS CLOSED • Hao’s moderators were racial profiling dark-skinned avatars • Habbo Hotel raided by blockading entrances of popular areas • Exploiting a technical issue that ould’t allow avatars to walk through each other when entering and exiting premises. 2006-2007 • Harold Charles "Hal" Turner (born March 15, 1962) is an American white nationalist, Holocaust denier and blogger from North Bergen, New Jersey. • Turner claimed that in December 2006 and January Anonymous took Turner's website offline, costing him thousands of dollars in bandwidth bills. • Turner sued 4chan and other websites for copyright infringement. • Turner failed to respond and the judge dismissed the case in December 2007. 2006-2007 • Chris Forcand arrest • Members of Anonymous had been researching Forcand and had posted online several chatlogs. • Pretended to be under aged girls, most notably a supposed 13 year old named Jessica. • The conversations were forwarded to the members of his church. • Toronto PD arrested him on December 5, 2007 after an undercover investigation. • Charged with two counts of luring a child under the age of 14, attempt to invite sexual touching, attempted exposure, possessing a dangerous weapon, and carrying a concealed weapon. 2008 • Project Chanology (Operation Chanology) was a protest movement against the practices of the Church of Scientology • Response to the Church of Scientology's attempts to remove material from a highly publicized interview with Tom Cruise from the Internet. -

March 24, 2008 the Free-Content News Source That You Can Write! Page 1

March 24, 2008 The free-content news source that you can write! Page 1 Top Stories Cheney meets with Israeli and state. Cheney noted "Terror and Palestinian leaders rockets do not merely kill innocent Ma Ying-jeou wins 2008 United States Vice President Dick civilians, they also kill the Taiwan presidential election Cheney met with the leaders as legitimate hopes and aspirations of Ma Ying-jeou, former Mayor of part of a tour of the Middle East the Palestinian people." Taipei, has been elected as the which is part of a plan to get a new President of the Republic of peace agreement between Israel The Vice President remarked he is China (Taiwan) with a landslide and the Palestinian by the end of committed towards a Palestinian victory of 58.45% of the popular Bush's term in January 2009. state, quoting President George W. vote. Bush, "The establishment of the Wikipedia Current Events state of Palestine is long overdue. Major US presidential The Palestinian people deserve it." candidates have passport files Farouk Abdulhak, prime suspect Cheney also noted that "Achieving breached in the murder of Martine Vik that vision will require tremendous Just hours after firing two Magnussen, turns up in Yemen. effort at the negotiating table and contract employees for •Kimi Räikkönen (Finland) wins painful concessions on both sides." inappropriately examining the the Malaysian Grand Prix in passport file of Democratic Sepang. Abbas condemned rocket attacks presidential candidate Barack against Israel from the Hamas- •An agreement on talks to resolve Obama, US Secretary of State controlled Gaza Strip, but also told the Fatah-Hamas conflict is Condoleezza Rice told Hillary Israel to ease their restrictions on reached in Sanaa, Yemen. -

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: the Story of Anonymous

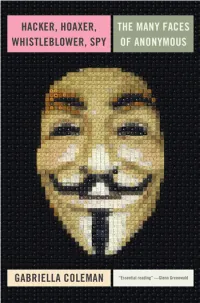

hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy the many faces of anonymous Gabriella Coleman London • New York First published by Verso 2014 © Gabriella Coleman 2014 The partial or total reproduction of this publication, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for noncommercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and the source are clearly acknowledged. Any reproduction or use of all or a portion of this publication in exchange for financial consideration of any kind is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-583-9 eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-584-6 (US) eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-689-8 (UK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the library of congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Press Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY I dedicate this book to the legions behind Anonymous— those who have donned the mask in the past, those who still dare to take a stand today, and those who will surely rise again in the future. -

Podcast Transcript Version 1.1, 14 November 2018

THE RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROJECT 1 Podcast Transcript Version 1.1, 14 November 2018 New Directions in the Study of Scientology Podcast with David Robertson, Carole Cusack, Stephen Gregg and Aled Thomas (19 November 2018). Transcribed by Helen Bradstock. Audio and transcript available at: http://www.religiousstudiesproject.com/podcast/new-directions-in- the-study-of-scientology/ David Robertson (DR): So we're here at the BASR Conference 2018, in Belfast. And I have gathered several colleagues together today to have a discussion about Scientology: the idea of new directions in the study of Scientology, and how do we move the conversation about Scientology forward? There’s a large number of different directions we can go in that conversation, so I'm not going to constrain it at this point by saying exactly what I mean by that. But we're going to start off by looking at some interesting data and approaches and move into a discussion of the larger methodological issues about the study of Scientology in relationship to NRMs and other more established religious traditions. And then we’ll end the conversation by opening it out to some interesting responses, in the coming week. But for now I'm going to start by going round the table and asking my colleagues to introduce themselves. Carole Cusack (CC): I'm Carole Cusack, I'm a professor of Religious Studies at the University of Sydney and I have a longstanding interest in Scientology. Aled Thomas (AT): Hi, I'm Aled Thomas, I'm a PhD candidate at the Open University and my research is on Free Zone Scientology. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Who Are Anonymous? A Study Of Online Activism Collins, Benjamin Thomas Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Who Are Anonymous? A Study Of Online Activism Benjamin Thomas Collins King's College London, War Studies 2016 1 Abstract The activist network “Anonymous” has protested and launched cyber-attacks for and against a spectrum of socio-political causes around the world since 2008.