1999. 851 Pages, $180.00 Rrp. 3) A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everyone Welcome Grey Butcherbird Robin Hide

Gang-gang JUNE 2020 Newsletter of the Canberra Ornithologists Group Inc. JUNE MEETING Summary/analysis of the past month and what to watch Wednesday 10 June 2020 out for this month virtual meeting After the very busy previous month, the very cold change that swept through There will be virtual meeting on 10 June. at the end of April/early May seemed to very much quieten bird activity in Arrangements for this are still being the COG area of Interest (AoI) for the 4 week period from 29 April covered by organised and COG members will be this column. This is despite the weather then warming up to around average separately advised of the details, temperatures with limited rain falling. For example, on the afternoon of 17 including how to participate. May, Mark Clayton and his wife took advantage of the glorious weather and decided to go for a drive just to see what birds were about. They left home The single speaker for this virtual meeting in Kaleen at about 1 pm and travelled via Uriarra Crossing all the way to will be Alice McGlashan on “Hollow using Angle Crossing Road, but could hardly find a bird. species and nest box designs for the Canberra region”. Andrea and I have been doing regular walks in the local area and have been also been remarking on the lack of birds. That same morning we walked Many of our local native birds and mammals use tree hollows for nesting or Continued Page 2 sleeping. Much of the native habitat in and around Canberra has a deficit of old hollow bearing trees, from land clearing and selective removal of large trees for timber and firewood. -

Sericornis, Acanthizidae)

GENETIC AND MORPHOLOGICAL DIFFERENTIATION AND PHYLOGENY IN THE AUSTRALO-PAPUAN SCRUBWRENS (SERICORNIS, ACANTHIZIDAE) LESLIE CHRISTIDIS,1'2 RICHARD $CHODDE,l AND PETER R. BAVERSTOCK 3 •Divisionof Wildlifeand Ecology, CSIRO, P.O. Box84, Lyneham,Australian Capital Territory 2605, Australia, 2Departmentof EvolutionaryBiology, Research School of BiologicalSciences, AustralianNational University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601, Australia, and 3EvolutionaryBiology Unit, SouthAustralian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia ASS•CRACr.--Theinterrelationships of 13 of the 14 speciescurrently recognized in the Australo-Papuan oscinine scrubwrens, Sericornis,were assessedby protein electrophoresis, screening44 presumptivelo.ci. Consensus among analysesindicated that Sericorniscomprises two primary lineagesof hithertounassociated species: S. beccarii with S.magnirostris, S.nouhuysi and the S. perspicillatusgroup; and S. papuensisand S. keriwith S. spiloderaand the S. frontalis group. Both lineages are shared by Australia and New Guinea. Patternsof latitudinal and altitudinal allopatry and sequencesof introgressiveintergradation are concordantwith these groupings,but many featuresof external morphologyare not. Apparent homologiesin face, wing and tail markings, used formerly as the principal criteria for grouping species,are particularly at variance and are interpreted either as coinherited ancestraltraits or homo- plasies. Distribution patternssuggest that both primary lineageswere first split vicariantly between -

Breeding Biology and Behaviour of the Scarlet

Corella, 2006, 30(3/4):5945 BREEDINGBIOLOGY AND BEHAVIOUROF THE SCARLETROBIN Petroicamulticolor AND EASTERNYELLOW ROBIN Eopsaltriaaustralis IN REMNANTWOODLAND NEAR ARMIDALE, NEW SOUTH WALES S.J. S.DEBUS Division of Zoology, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales 2351 E-mail: [email protected] Received:I3 January 2006 The breeding biology and behaviour of the Scarlet Robin Petroica multicolor and Eastern Yellow Robin Eopsaltria australis were studied at lmbota Nature Reserve, on the New England Tableland of New South Wales,in 200G-2002by colour-bandingand nest-monitoring.Yellow Robins nested low in shelteredpositions, in plants with small stem diameters(mostly saplings,live trees and shrubs),whereas Scarlet Robins nested high in exposed positions, in plants with large stem diameters (mostly live trees, dead branches or dead trees).Yellow Robin clutch size was two or three eggs (mean 2.2; n = 19). Incubationand nestling periods were 15-17 days and 11-12 days respectively(n = 6) for the Yellow Robin, and 16-18 days (n = 3) and 16 days (n = 1) respectivelyfor the ScarletRobin. Both specieswere multi-brooded,although only YellowRobins successfully raised a second brood. The post-fledging dependence period lasted eight weeks for Yellow Robins, and six weeks for Scarlet Robins. The two robins appear to differ in their susceptibilityto nest predation, with corresponding differences in anti-predator strategies. INTRODUCTION provides empirical data on aspects that may vary geographicallywith seasonalconditions, or with habitator The -

Hunter Economic Zone

Issue No. 3/14 June 2014 The Club aims to: • encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat • encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity A Black-necked Stork pair at Hexham Swamp performing a spectacular “Up-down” display before chasing away the interloper - in this case a young female - Rod Warnock CONTENTS President’s Column 2 Conservation Issues New Members 2 Hunter Economic Zone 9 Club Activity Reports Macquarie Island now pest-free 10 Glenrock and Redhead 2 Powling Street Wetlands, Port Fairy 11 Borah TSR near Barraba 3 Bird Articles Tocal Field Days 4 Plankton makes scents for seabirds 12 Tocal Agricultural College 4 Superb Fairy-wrens sing to their chicks Rufous Scrub-bird Monitoring 5 before birth 13 Future Activity - BirdLife Seminar 5 BirdLife Australia News 13 Birding Features Birding Feature Hunter Striated Pardalote Subspecies ID 6 Trans-Tasman Birding Links since 2000 14 Trials of Photography - Oystercatchers 7 Club Night & Hunterbirding Observations 15 Featured Birdwatching Site - Allyn River 8 Club Activities June to August 18 Please send Newsletter articles direct to the Editor, HBOC postal address: Liz Crawford at: [email protected] PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Deadline for the next edition - 31 July 2014 Website: www.hboc.org.au President’s Column I’ve just been on the phone to a lady that lives in Sydney was here for a few days visiting the area, talking to club and is part of a birdwatching group of friends that are members and attending our May club meeting. -

Notes on the Breeding Behaviour of the Red-Capped Robin Petroica Goodenovii

VOL. 12 (7) SEPTEMBER 1988 209 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1988, 12, 209-216 Notes on the Breeding Behaviour of the Red-capped Robin Petroica goodenovii by PETER COVENTRY, 12 Baroona Avenue, Cooma North, N.S.W. 2630 Summary Three pairs of Red-capped Robins Petroica goodenovii were studied on the Southern Tablelands of' New South Wales during a temporary invasion in 1981-1983, at the end of a drought. The birds arrived in spring, the males ahead of the females, and defended territories against Scarlet Robins P. TTUilticolor. One male Red-capped Robin uttered the Scarlet Robin's song during territory advertisement. After raising one or two broods the birds dispersed for the winter, the adults either at the same time as or after the departure of juveniles. After breeding the adults moulted, the females starting before the males. Nests were built, by females only, at a height of 2-6m (mean 3.6 m), and took 5-9 days (mean 8 days) to complete. Eggs were laid between mid October and late December. Mean clutch size was 1.9 eggs (1-2, mode 2), and mean brood size at fledging was 1.4 (1-2, mode I). Incubation lasted 14 days (three clutches), the nestling period was 11-16 days (mean 12.5 days) and the post fledging dependence period lasted at least two weeks. The breeding success rate was 54% (7 fledglings from 13 eggs), and the nest success rate was 63% (5 nests successful out of 8 for which the outcome was known). Nest-building, courtship, parental behaviour and vocalisations are described. -

Fleurieu Birdwatch Newsletter of Fleurieu Birdwatchers Inc June 2002

fleurieu birdwatch Newsletter of Fleurieu Birdwatchers Inc June 2002 Meetings: Anglican Church Hall, cnr Crocker and Cadell Streets, Goolwa 7.30 pm 2nd Friday of alternate (odd) months Outings: Meet 8.30 am. Bring lunch and a chair — see Diary Contacts: Judith Dyer, phone 8555 2736 Ann Turner, phone 8554 2462 30 Woodrow Way, Goolwa 5214 9 Carnegie Street, Pt Elliot 5212 Web site: under reconstruction Newsletter: Verle Wood, 13 Marlin Terrace, Victor Harbor 5211, [email protected] DIARY DATES ✠ Wednesday 14 August Onkaparinga Wetlands ✠ Wednesday 12 June Meet at the park by the Institute, Old Kyeema Noarlunga Meet at corner of Meadows to Willunga Road ✠ Friday 16 August and Woodgate Hill Road. Annual Dinner ✠ Saturday 22 June Cox Scrub — north-eastern corner Meet in car park at northern end of park off Ashbourne Road. Once-a-year night ✠ Friday 12 July Meeting Program to be arranged Dinner ✠ Sunday 14 July at the Hotel Victor Goolwa Effluent Ponds 7 pm Friday 16 August Meet at the effluent ponds, Kessell Road, Goolwa. 3 Courses — $15 ✠ Wednesday 24 July Normanville and Bungalla Creek Bookings essential Meet in the car park on the foreshore. Contact Gaynor 8555 5480 ✠ Saturday 3 August or Verle 8552 2197 [email protected] Cox Scrub — south-eastern corner Meet in car park on the southern boundary at junction of Ashbourne and Bond Roads. MEETING WELCOME Friday 10 May 16 members attended this meeting and were Ruth Piesse, Parkholme welcomed by Gaynor Jones, Chairperson. Gaynor reported that Alexandrina Council We hope you will enjoy is working on extensions to the stormwater your birdwatching activities mitigation wetlands development at Burns Road, with us. -

Spring Bird Surveys in the Gloucester Tops

Gloucester Tops bird surveys The Whistler 13 (2019): 26-34 Spring bird surveys in the Gloucester Tops Alan Stuart1 and Mike Newman2 181 Queens Road, New Lambton, NSW 2305, Australia [email protected] 272 Axiom Way, Acton Park, Tasmania 7021, Australia [email protected] Received 14 March 2019; accepted 11 May 2019; published on-line 15 July 2019 Spring surveys between 2010 and 2017 in the Gloucester Tops in New South Wales recorded 92 bird species. The bird assemblages in three altitude zones were characterised and the Reporting Rates for individual species were compared. Five species (Rufous Scrub-bird Atrichornis rufescens, Red-browed Treecreeper Climacteris erythrops, Crescent Honeyeater Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus, Olive Whistler Pachycephala olivacea and Flame Robin Petroica phoenicea) were more likely to be recorded at high altitude. The Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Cacatua galerita, Brown Cuckoo-Dove Macropygia phasianella and Wonga Pigeon Leucosarcia melanoleuca were less likely to be recorded at high altitude. All these differences were statistically significant. Two species, Paradise Riflebird Lophorina paradiseus and Bell Miner Manorina melanophrys, were more likely to be recorded at mid-altitude than at high altitude, and had no low-altitude records. The differences were statistically significant. Many of the 78 species found at low altitude were infrequently or never recorded at higher altitudes and for 18 species, the differences warrant further investigation. There was only one record of the Regent Bowerbird Sericulus chrysocephalus and evidence is provided that this species may have become uncommon in the area. The populations of Green Catbird Ailuroedus crassirostris, Australian Logrunner Orthonyx temminckii and Pale-yellow Robin Tregellasia capito may also have declined. -

Download Full Text (Pdf)

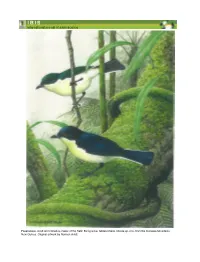

FRONTISPIECE. Adult and immature males of the Satin Berrypecker Melanocharis citreola sp. nov. from the Kumawa Mountains, New Guinea. Original artwork by Norman Arlott. Ibis (2021) doi: 10.1111/ibi.12981 A new, undescribed species of Melanocharis berrypecker from western New Guinea and the evolutionary history of the family Melanocharitidae BORJA MILA, *1 JADE BRUXAUX,2,3 GUILLERMO FRIIS,1 KATERINA SAM,4,5 HIDAYAT ASHARI6 & CHRISTOPHE THEBAUD 2 1National Museum of Natural Sciences, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Madrid, 28006, Spain 2Laboratoire Evolution et Diversite Biologique, UMR 5174 CNRS-IRD, Universite Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France 3Department of Ecology and Environmental Science, UPSC, Umea University, Umea, Sweden 4Biology Centre of Czech Academy of Sciences, Institute of Entomology, Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic 5Faculty of Sciences, University of South Bohemia, Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic 6Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Cibinong, Indonesia Western New Guinea remains one of the last biologically underexplored regions of the world, and much remains to be learned regarding the diversity and evolutionary history of its fauna and flora. During a recent ornithological expedition to the Kumawa Moun- tains in West Papua, we encountered an undescribed species of Melanocharis berrypecker (Melanocharitidae) in cloud forest at an elevation of 1200 m asl. Its main characteristics are iridescent blue-black upperparts, satin-white underparts washed lemon yellow, and white outer edges to the external rectrices. Initially thought to represent a close relative of the Mid-mountain Berrypecker Melanocharis longicauda based on elevation and plu- mage colour traits, a complete phylogenetic analysis of the genus based on full mitogen- omes and genome-wide nuclear data revealed that the new species, which we name Satin Berrypecker Melanocharis citreola sp. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

Scarlet Robin (Female). Yellow Robin

Scarlet Robin (Female). Yellow Robin. Photos. by H. A. C. beach. R.A.O.U. Red-capped Robin (Female). Hooded Robin (Male). Photos. by H. A. C. Leach, R.A.O.U. Robins By HUGH A. C. LEACH, R.A.O.U., Castlemaine, Vic. I still remember the pleasure felt on finding my first nest of the Hooded Robin (Melanodryas cucullata). It was placed on the fire-blackened side of a grey stump, and was made of bark similar in colour to the stump. This is the usual nesting site for these birds, but they also build low down in the fork of a growing tree. The eggs, two or three in number, are green. When only the eggs were present in the nest described above, the mother bird took very little notice of me, but when the young ones appeared, she adopted the ruse of the White-fronted Chat or Tang (Epthianura albifrons) of fluttering away along the ground, but, unlike the Tang, she rolled over and over. Finding that I would not pursue her she came back, climbed up behind a fairly large rock and rolled down towards me. For amusement I followed her and she continued rolling over logs and rocks for some little distance. The male bird is easily distinguished from his mate, as he has a black hood and a black back. The underparts are white, and white feathers show on the shoulders and wings. The female is greyish-white underneath and has a grey head and back. No difficulty is experienced in obtaining pictures of the female for she is delightfully tame. -

Spring Bird Communities of a High-Altitude Area of the Gloucester Tops, New South Wales

Australian Field Ornithology 2018, 35, 21–29 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo35021029 Spring bird communities of a high-altitude area of the Gloucester Tops, New South Wales Alan Stuart1 and Mike Newman2 181 Queens Road, New Lambton NSW 2305, Australia. Email: [email protected] 272 Axiom Way, Acton Park TAS 7021, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Annual spring surveys between 2010 and 2016 in a 5000-ha area in the Gloucester Tops in New South Wales recorded 71 bird species. All the study area was at altitudes >1100 m. The monitoring program was carried out with involvement of a team of volunteers, who regularly surveyed 21 1-km transects, for a total of 289 surveys. The study area was within the Barrington Tops and Gloucester Tops Key Biodiversity Area (KBA). The trigger species for the KBA listing was the Rufous Scrub-bird Atrichornis rufescens, which was found to have a widespread distribution in the study area, with an average Reporting Rate (RR) of 56.5%. Another species cited in the KBA nomination, the Flame Robin Petroica phoenicea, had an average RR of 12.6% but with considerable annual variation. Although the Flame Robin had a widespread distribution, one-third of all records came from just two of the 21 survey transects. Thirty-seven bird species had RRs >4% in the study area and were distributed across many transects. Of these, 20 species were relatively common, with RRs >20%, and they occurred in all or nearly all of the survey transects. Introduction shrubs such as Banksia species (Binns 1995). -

Adobe PDF, Job 6

Noms français des oiseaux du Monde par la Commission internationale des noms français des oiseaux (CINFO) composée de Pierre DEVILLERS, Henri OUELLET, Édouard BENITO-ESPINAL, Roseline BEUDELS, Roger CRUON, Normand DAVID, Christian ÉRARD, Michel GOSSELIN, Gilles SEUTIN Éd. MultiMondes Inc., Sainte-Foy, Québec & Éd. Chabaud, Bayonne, France, 1993, 1re éd. ISBN 2-87749035-1 & avec le concours de Stéphane POPINET pour les noms anglais, d'après Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World par C. G. SIBLEY & B. L. MONROE Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990 ISBN 2-87749035-1 Source : http://perso.club-internet.fr/alfosse/cinfo.htm Nouvelle adresse : http://listoiseauxmonde.multimania.