Recorder 16 2017.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the Differences Between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the differences between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas This document should be read in conjunction with the School Places Strategy 2017 – 2022 and provides an explanation of the differences between the Wiltshire Community Areas served by the Area Boards and the School Planning Areas. The Strategy is primarily a school place planning tool which, by necessity, is written from the perspective of the School Planning Areas. A School Planning Area (SPA) is defined as the area(s) served by a Secondary School and therefore includes all primary schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into that secondary school. As these areas can differ from the community areas, this addendum is a reference tool to aid interested parties from the Community Area/Area Board to define which SPA includes the schools covered by their Community Area. It is therefore written from the Community Area standpoint. Amesbury The Amesbury Community Area and Area Board covers Amesbury town and surrounding parishes of Tilshead, Orcheston, Shrewton, Figheldean, Netheravon, Enford, Durrington (including Larkhill), Milston, Bulford, Cholderton, Wilsford & Lake, The Woodfords and Great Durnford. It encompasses the secondary schools The Stonehenge School in Amesbury and Avon Valley College in Durrington and includes primary schools which feed into secondary provision in the Community Areas of Durrington, Lavington and Salisbury. However, the School Planning Area (SPA) is based on the area(s) served by the Secondary Schools and covers schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into either The Stonehenge School in Amesbury or Avon Valley College in Durrington. -

The Wool Store High Street Codford St Peter a Study by Sally Thomson, Clive Carter & Dorothy Treasure January 2006

WILTSHIRE BUILDINGS RECORD North Elevation in January 2006 during conversion to flats The Wool Store High Street Codford St Peter A Study By Sally Thomson, Clive Carter & Dorothy Treasure January 2006 Wiltshire Buildings Record, Libraries and Heritage HQ, Bythesea Road, Trowbridge, Wilts BA14 8BS Tel. Trowbridge (01225) 713740 Open Tuesdays Contents 1. Summary & acknowledgements 2. Documentary History 3. Maps 2 SUMMARY NGR: ST 9676 3986 In accordance with instruction by Matthew Bristow for the England’s Past For Everyone Project a study comprising an historical appraisal of the Wool Store was undertaken in January 2005. The results, incorporated in the following report, present a photographic, drawn and textual record supported by cartographic and documentary evidence where relevant, of the structure as it now stands. This is followed by a cautious archaeological interpretation. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Client: England’s Past for Everyone, Institute of Historical Research, University of London, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. Contact: Mr Matthew Bristow 020 7664 4899 e-mail [email protected] Wool Store Contact: Mr Paul Hember, The Wool House, High Street, Codford, Wiltshire BA12 0NE Tel. 01985 850152 Project Personnel: Dorothy Treasure (Organiser), Sally Thomson (Researcher), Clive Carter (Architectural Technician), Wiltshire Buildings Record, Libraries and Museum HQ, Bythesea Road, Trowbridge, Wiltshire BA14 8BS e-mail [email protected] 3 THE WOOLSTORE, CODFORD INTRODUCTION Constructing a meaningful history of the Woolstore is extremely difficult in the absence of relevant detailed documentation. The Department of the Environment lists it as a ‘woollen mill’ and ‘early 19th century’.1 These two statements alone demand explanation. -

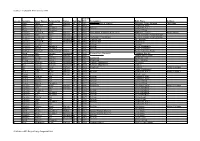

Teffont Magna - Census 1861

Teffont Magna - Census 1861 2 2 3 Relationship Year /1 Abode Surname Given Names Status Age Sex Occupation Place of Birth Notes 9 to Head Born G R 1 Macey John George Head U 64 M 1797 Cooper Teffont Page 1. Folio 60 ed4 Macey James Brother W 58 M 1803 Cooper Teffont Macey Fred Geo Nephew U 26 M 1835 Cooper Fovant Macey Ethel Ann Neice U 24 F 1837 Fovant 2 Barratt Henry Head M 49 M 1812 Plumber & Glazier Warminster Barratt Mary A Wife M 52 F 1809 Knoyle Barratt Edwin Son U 24 M 1837 Plumber & Glazier Teffont Barratt Mary A Dau U 21 F 1840 Teffont 3 Euence Elizabeth Head W 63 F 1798 Teffont 4 Obrien James Head M 43 M 1818 Ag. Lab Teffont Obrien Sophia Wife M 40 F 1821 Teffont Obrien Elizabeth Dau 13 F 1848 Scholar Teffont Obrien Maria Dau 13 F 1848 Scholar Teffont Obrien Mary Ann Dau 10 F 1851 Scholar Teffont Obrien John Son 7 M 1854 Scholar Teffont Ford James Lodger U 50 M 1811 Ag. Lab Teffont 5 Mullins William Head M 56 M 1805 Ag. Lab Teffont Mullins Elizabeth Wife M 53 F 1808 Teffont Mullins George Son U 16 M 1845 Ag. Lab Teffont Mullins James Son U 13 M 1848 Scholar Teffont Mullins Thomas Son 10 M 1851 Scholar Teffont Mullins Mary J Dau 7 F 1854 Scholar Teffont 6 Kellow Job Head M 62 M 1799 Ag. Lab Teffont Page 2 Kellow Mary Wife M 62 F 1799 Dinton Kellow Elizabeth Dau U 25 F 1836 Teffont Kellow Thomas Son U 19 M 1842 Ag. -

Ashton Gifford Coach House Codford St Peter, Wiltshire Ashton Gifford Coach House Codford St Peter, Wiltshire, Ba12 0Jx

Ashton Gifford Coach House Codford St Peter, Wiltshire Ashton Gifford Coach House Codford St Peter, Wiltshire, ba12 0jx Attractive Former Coach House With Potential To Modernise And/Or Divide Into Two Separate Dwellings With Adjoining Annexe Drawing room | dining room garden room | kitchen/breakfast room 2 studies | utility | 2 cloakrooms master bedroom with dressing room and en-suite | 6 further bedrooms 2 family bathrooms | WC Self contained adjoining 2 bedroom annexe Planning consent to divide the property into two separate dwellings (one with an attached annexe) About 1.3 acres DESCRIPTION Believed to date from around 1790, the Coach House was built as the coach house In addition there is a rear hall, two studies, two cloakrooms and various utility to the neighbouring Ashton Gifford House. The house is situated near the end of a rooms and stores on the ground floor. private road and has views out across the surrounding farmland. Upstairs there are currently seven bedrooms, one with an en-suite, as well as two Constructed of stone under a slate roof the property is currently laid out in a U- further bathrooms and a separate WC. Two of the bedrooms have access out onto shape around a central courtyard. a balcony with views across the garden. The property currently extends to 6726sq ft including a two bedroom annexe The property is in need of some updating and modernisation throughout. and offers flexible accommodation arranged over two floors. There is planning permission to divide the house into two separate dwellings (The Coach House ANNEXE with adjoining annexe and The Harness House as shown on the floor plan). -

Codford - Codford St

Codford - Codford St. Peter Census 1881 Year of Schedule Surname Given Names Relationship Status Sex Age Birth Occupation Birth Place Address 1 Stone Henry Head Married M 24 1857 Woolsorter (out of employ) Somerset, Frome Selwood The Lodge Stone Isabella L. Wife Married F 22 1859 Codford St. Mary Stone Minnie L. Daughter F 3 1878 Scholar Codford St. Peter Stone Edith E. Daughter F 0 1881 Ashton Gifford 2 Clement George A. Head Married M 48 1833 Race Horse Trainer (Employing 4 boys) Middlesex, Pimlico Ashton House Clement Edith Wife Married F 48 1833 Berks., Letcombe Regis Wantage Clement George W. Son Unmarried M 19 1862 Huntsman / Trainers Son Berks., Letcombe Regis Wantage Clement Arthur G. Son Unmarried M 18 1863 Trainers Son All Cannings Clement Charles B. Son Unmarried M 16 1865 Trainers Son Heddington Clement Alfred L. Son M 14 1867 Scholar Devizes Clement Edith S. Daughter F 7 1874 Scholar Berks., Lambourne Clement Mary E. Daughter F 5 1876 Scholar Berks., Lambourne Godfrey Elizabeth Mother-in-Law Widow F 87 1794 Berks., Letcombe Regis Smith Ada Servant Unmarried F 16 1865 General Serv (Domestic) Yorkshire, Roe Hill 3 Curlis (Curtis) Ellen Wife Married F 55 1826 Dairymans Wife London, Mile End Rd. Slatter George Boarder Unmarried M 21 1860 Stableman Burton-on Trent Peyton Albert Boarder Unmarried M 20 1861 Stableman Birks., Alington Colt (Or Cox) Abraham Boarder Unmarried M 21 1860 Trainer's (Apprentice) Worcestor Doe Samuel Boarder Unmarried M 16 1865 Trainer's (Apprentice) London 4 Kill Lemuel Head Married M 72 1809 Shepherd Codford Ashton Cottages Kill Elizabeth Wife Married F 71 1810 Hants., Rockbourne 5 Dewey John Head Married M 38 1843 Ag. -

Codford St. Mary Roll of Honour ARTHUR CHARLES POND

Codford St. Mary Roll of Honour Lest we Forget World War I 6558 PRIVATE ARTHUR CHARLES POND 11TH BN AUSTRALIAN INFANTRY A.I.F. 10TH AUGUST, 1918 ©Wiltshire OPC Project/Cathy Sedgwick/2013 Arthur Charles POND Arthur Charles Pond was born in 1890 at Little Sutton Farm, Sutton Parva, near Heytesbury, Wiltshire, to parents William & Maria Pond (nee Arnold). His birth was registered in the district of Warminster, Wiltshire in the September quarter of 1890. The 1891 Census for England recorded Arthur Pond as an 8 month old living with his family at 9 Sutton Pava, Sutton Veny, Wiltshire. His parents were listed as William Pond (Farmer, aged 41, born Motcombe, Dorset) & Maria Pond (aged 37, born Chilmark, Wilts). There were 6 children listed in this census, Arthur being the youngest – Frank (aged 9, born Shaftesbury, Dorset), Sidney (aged 8, born Shaftesbury, Dorset), Kathleen (aged 6, born Gillingham, Dorset), Maud (aged 4 born Sutton Veny), Lily M (aged 2, born Sutton Veny) & then Arthur. Also included was Winifred Snelgrove (General Servant, aged 15, born Sutton Veny). The 1901 Census for England recorded Arthur Pond as a 10 year old living with his family at Sutton Parva Farm, Sutton Veny. His parents were listed as William Pond (Farmer, aged 51) & Maria Pond (aged 47). There were 6 children listed on this Census – Mabel A. (aged 21), Sidney (aged 18), Lillie (aged 12, born Sutton Parva), then Arthur(born Sutton Parva), May M. (aged 8, born Sutton Parva) & Dorothy M. (aged 5, born Sutton Parva). Arthur Charles Pond attended Emwell House Private School in Warminster. -

WILTSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position WI_AMAV00 SU 15217 41389 UC road AMESBURY Church Street; opp. No. 41 built into & flush with churchyard wall Stonehenge Road; 15m W offield entrance 70m E jcn WI_AMAV01 SU 13865 41907 UC road AMESBURY A303 by the road WI_AMHE02 SU 12300 42270 A344 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due N of monument on the Verge Winterbourne Stoke Down; 60m W of edge Fargo WI_AMHE03 SU 10749 42754 A344 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Plantation on the Verge WI_AMHE05 SU 07967 43180 A344 SHREWTON Rollestone top of hill on narrow Verge WI_AMHE06 SU 06807 43883 A360 SHREWTON Maddington Street, Shrewton by Blind House against wall on Verge WI_AMHE09 SU 02119 43409 B390 CHITTERNE Chitterne Down opp. tank crossing next to tree on Verge WI_AMHE12 ST 97754 43369 B390 CODFORD Codford Down; 100m W of farm track on the Verge WI_AMHE13 ST 96143 43128 B390 UPTON LOVELL Ansty Hill top of hill,100m E of line of trees on Verge WI_AMHE14 ST 94519 42782 B390 KNOOK Knook Camp; 350m E of entrance W Farm Barns on bend on embankment WI_AMWH02 SU 12272 41969 A303 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due S of monument on the Verge WI_AMWH03 SU 10685 41600 A303 WILSFORD CUM LAKE Wilsford Down; 750m E of roundabout 40m W of lay-by on the Verge in front of ditch WI_AMWH05 SU 07482 41028 A303 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Winterbourne Stoke; 70m W jcn B3083 on deep verge WI_AMWH11 ST 990 364 A303 STOCKTON roadside by the road WI_AMWH12 ST 975 356 A303 STOCKTON 400m E of parish boundary with Chilmark by the road WI_AMWH18 ST 8759 3382 A303 EAST KNOYLE 500m E of Willoughby Hedge by the road WI_BADZ08 ST 84885 64890 UC road ATWORTH Cock Road Plantation, Atworth; 225m W farm buildings on the Verge WI_BADZ09 ST 86354 64587 UC road ATWORTH New House Farm; 25m W farmhouse on the Verge Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. -

Upper Deverills Parish Plan

Brixton Deverill Monkton Deverill Kingston Deverill Foreword by Andrew Murrison MP I am delighted to introduce this Parish Plan which is the work of the residents in Brixton Deverill, Kingston Deverill and Monkton Deverill. All involved, including those who responded to questionnaires and came to consultations, the Parish Council and the Plan Team, are to be congratulated on a document of real worth and great potential utility. It should serve the Parish well for several years. The planning authority, Wiltshire Council, will always benefit from local input in addressing the particular needs of small communities, especially when resources are scarce. Community action has therefore become very much the way forward when residents want something to happen. This formal expression of the Parish’s ambitions and needs is the first and most important foundation for future effective action. The preparation of a Village Design Statement is suggested. We are all very lucky to be living in such a beautiful part of England and such beauty needs to be nurtured and protected. A Design Statement is one way of doing this and I very much encourage the further work it will require. The Parish needs also to evolve and develop in its appeal across the generations of the families already here and to come. So some change is necessary, and this plan, in the process of its preparation, makes that possible. The Plan is a good piece of work and its authors are to be congratulated. House of Commons Andrew Murrison MD MP Upper Deverills Parish Plan Contents Foreword -

Berwick St. Leonard - Census 1851

Berwick St. Leonard - Census 1851 YEAR SCHEDULE SURNAME FORENAMES RELATIONSHIP C0NDITION SEX AGE BORN OCCUPATION PLACE OF BIRTH ABODE 1 Gray John Head Widower m 67 1784 Parish Clerk Mere Berwick St Leonard 2 Deverill Job Head Widower m 43 1808 Farm Labourer Fonthill Bishop Berwick St Leonard 3 Gray Roger Head Married m 59 1792 Farm Labourer Fonthill Bishop Berwick St Leonard 3 Gray Ann Wife Married f 57 1794 Hindon Berwick St Leonard 3 Gray Maria Daughter Unmarried f 27 1824 Berwick St Leonard Berwick St Leonard 3 Gray Mary Daughter f 15 1836 Berwick St Leonard Berwick St Leonard 3 Gray James Son m 12 1839 Farm Labourer Berwick St Leonard Berwick St Leonard 3 Gray Jane Granddaughter f 5 1846 Berwick St Leonard Berwick St Leonard 4 Blandford William Head Married m 66 1785 Woodman Tisbury Penning 4 Blandford Martha Wife Married f 64 1787 Tisbury Penning 5 Hibberd Thomas Head Married m 69 1782 Farm Labourer Hindon Penning 5 Hibberd Mary Wife Married f 73 1778 Hindon Penning 6 Gray George Head Married m 25 1826 Farm Labourer Berwick St Leonard Berwick St Leonard 6 Gray Elizabeth Wife Married f 25 1826 Fonthill Gifford Berwick St Leonard 6 Gray Henry Son m 3 1848 Berwick St Leonard Berwick St Leonard 6 Gray William Son m 0 1851 Berwick St Leonard Berwick St Leonard 7 Hibberd John Head Married m 27 1824 Farm Labourer Berwick St Leonard Berwick St Leonard 7 Hibberd Harriet Wife Married f 22 1829 Berwick St Leonard Berwick St Leonard 8 Pearce Robert Head Married m 47 1804 Agricultural Labourer Berwick St Leonard Berwick St Leonard 8 Pearce Catherine -

The Mill House CHICKSGROVE TISBURY WILTSHIRE

the mill house CHICKSGROVE TISBURY WILTSHIRE the mill house CHICKSGROVE TISBURY WILTSHIRE An enchanting mill house on the River Nadder Reception Hall, Drawing Room, Dining Room, Sitting Room, Gallery, Kitchen/Breakfast Room, Boot Room, Utility Room, 2 Cloakrooms 8 Bedrooms, 5 Bath/Shower Rooms, 2 Dressing Rooms, Box Room Riverside terraces, extensive mature Gardens with Mill leat Former Coach House comprising Stables with Hayloft, separate Tack Room Brick Outbuilding Double and single bank fishing rights on the River Nadder In all about 3.3 Acres Further Cottage and land available by separate negotiation Savills London Lansdowne House, 57 Berkeley Square, London W1J 6ER Tel: 0207 016 3780 [email protected] Savills Salisbury Rolfes House, 60 Milford Street, Salisbury SP1 2BP Tel: 01722 426820 [email protected] These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation The Mill House is nestled on the banks of the Upper Nadder Sporting facilities in the area include golf courses at Rushmore and within the sought after and unspoilt village of Chicksgrove, which South West Wilts. Racing at Salisbury and Wincanton. Hunting has a wealth of period houses and cottages. The surrounding with the South and West Wilts. There is an extensive network area is highly regarded for its beautiful undulating countryside, of bridleways and footpaths locally. A full range of watersports flora and fauna and is within an Area of Outstanding Natural are within easy reach along the Dorset coast. -

Wiltshire - Contiguous Parishes (Neighbours)

Wiltshire - Contiguous Parishes (Neighbours) Central Parish Contiguous Parishes (That is those parishes that have a border touching the border of the central parish) Aldbourne Baydon Chiseldon Draycote Foliat Liddington Little Hinton Mildenhall Ogbourne St. George Ramsbury Wanborough Alderbury & Clarendon Park Britford Downton Laverstock & Ford Nunton & Bodenham Pitton & Farley Salisbury West Grimstead Winterbourne Earls Whiteparsh Alderton Acton Turville (GLS) Hullavington Littleton Drew Luckington Sherston Magna All Cannings Avebury Bishops Cannings East Kennett Etchilhampton Patney Southbroom Stanton St. Bernard Allington Amesbury Boscombe Newton Tony Alton Barnes Alton Priors Stanton St. Bernard Woodborough Alton Priors Alton Barnes East Kennett Overton Wilcot Woodborough Alvediston Ansty Berwick St. John Ebbesbourne Wake Swallowcliffe Amesbury Allington Boscombe Bulford Cholderton Durnford Durrington Idmiston Newton Tony Wilsford Winterbourne Stoke Ansty Alvediston Berwick St. John Donhead St. Andrew Swallowcliffe Tisbury with Wardour Ashley Cherington (GLS) Crudwell Long Newnton Rodmarton (GLS) Tetbury (GLS) Ashton Keynes Cricklade St. Sampson Leigh Minety Shorncote South Cerney (GLS) Atworth Box Broughton Gifford Corsham Great Chalfield Melksham South Wraxall Avebury All Cannings Bishops Cannings Calstone Wellington Cherhill East Kennett Overton Winterbourne Monkton Yatesbury Barford St. Martin Baverstock Burcombe Compton Chamberlain Groveley Wood Baverstock Barford St. Martin Compton Chamberlain Dinton Groveley Wood Little Langford -

Sutton Mandeville

Foot and Mouth Disease Sutton Mandeville FOOT-AND-MOUTH DISEASE A return of parishes and places in the county of Wilts in which contagious or infectious disease exists among animals for the week ending Saturday, the 13th July, 1872 :- Police Divisions of Bradford and Trowbridge – Bradford-on-Avon, Broughton Gifford, Cottles, ……Hindon – Brixton Deverill, Donhead St. Mary, East Knoyle, East Tisbury, Fonthill Bishop, Kingston Deverill, Monkton Deverill, Mere, Sutton Mandeville, Wardour, West Knoyle, West Tisbury. Malmesbury – Ashton Keynes, Ashley………… (Salisbury and Winchester Journal - Saturday 20 July, 1872) A return of parishes and places in the county of Wilts in which contagious or infectious disease exists among animals for the week ending Saturday, 3rd August, 1872 :- POLICE DIVISIONS PARISHES Foot and Mouth Disease Bradford and Trowbridge – Bradford-on-Avon, Broughton Gifford, …….. Chippenham – Alderton, Avon, ………… Devizes – Beechingstoke, Bishop’s Cannings, …………. Hindon - Brixton Deverill, Donhead St. Mary, Dinton, East Knoyle, East Tisbury, Fonthill Bishop, Kingston Deverill, Monkton Deverill, Mere, Sedgehill, Semley, Stourton, Sutton Mandeville, Teffont Magna, Upper Pertwood, West Tisbury, West Knoyle, Wardour. ……….. (Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette - Thursday 8 August, 1872) ©Wiltshire OPC Project/Cathy Sedgwick/2013 A return of parishes and places in the county of Wilts in which contagious or infectious disease exists among animals for the week ending Saturday, 21st September, 1872 :- POLICE DIVISIONS PARISHES Foot and Mouth Disease Bradford and Trowbridge – Bradford-on-Avon, Broughton Gifford, …….. Chippenham – Alderton, Bremhill, ………… Devizes – Allcannings, …………. Hindon – Ansty, Brixton Deverill, Compton Chamberlayne, Dinton, Donhead St. Andrew, Ebbesborne, East Knoyle, East Tisbury, Fonthill Gifford, Kingston Deverill, Mere, Semley, Sutton Mandeville, Wardour, West Knoyle, West Tisbury.