UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available. Please Let Us Know How This Has Helped You. Thanks! Downlo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PME1 Schools List 2019-20

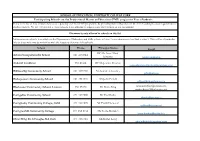

SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK Participating Schools on the Professional Master of Education (PME) 2019/20 for Year 1 Students Below is the list of Post-Primary Schools co-operating on UCC's PME programme by providing School Placement in line with Teaching Council requirements for student teachers. We are very grateful to these schools for continuing to support such a key element of our programme Placement is only allowed in schools on this list. Information on schools is available on the Department of Education and Skills website at http://www.education.ie/en/find-a-school. This will be of particular help to those who may be unfamiliar with the locations of some of the schools. School Phone Principal Name Email DP Ms Anne Marie Ashton Comprehensive School 021 4966044 Hewison [email protected] Ardscoil na nDeise 058 41464 DP Ms Joanne Brosnan [email protected] Ballincollig Community School 021 4871740 Ms Kathleen Lowney [email protected] Bishopstown Community School 021 4544311 Mr John Farrell [email protected] Blackwater Community School, Lismore 058 53620 Mr Denis Ring [email protected]; [email protected] Carrigaline Community School 021 4372300 Mr Paul Burke [email protected] Carrignafoy Community College, Cobh 021 4811325 Mr Frank Donovan [email protected] Carrigtwohill Community College 021 485 3488 Ms Lorna Dundon [email protected] Christ King SS, S Douglas Rd, Cork 021 4961448 Ms Richel Long [email protected] Christian Brothers College, Cork 021 4501653 Mr. David -

Mary Macswiney Was First Publicly Associated

MacSwiney, Mary by Brian Murphy MacSwiney, Mary (1872–1942), republican, was born 27 March 1872 at Bermondsey, London, eldest of seven surviving children of an English mother and an Irish émigré father, and grew up in London until she was seven. Her father, John MacSwiney, was born c.1835 on a farm at Kilmurray, near Crookstown, Co. Cork, while her mother Mary Wilkinson was English and otherwise remains obscure; they married in a catholic church in Southwark in 1871. After the family moved to Cork city (1879), her father started a snuff and tobacco business, and in the same year Mary's brother Terence MacSwiney (qv) was born. After his business failed, her father emigrated alone to Australia in 1885, and died at Melbourne in 1895. Nonetheless, before he emigrated he inculcated in all his children his own fervent separatism, which proved to be a formidable legacy. Mary was beset by ill health in childhood, her misfortune culminating with the amputation of an infected foot. As a result, it was at the late age of 20 that she finished her education at St Angela's Ursuline convent school in 1892. By 1900 she was teaching in English convent schools at Hillside, Farnborough, and at Ventnor, Isle of Wight. Her mother's death in 1904 led to her return to Cork to head the household, and she secured a teaching post back at St Angela's. In 1912 her education was completed with a BA from UCC. The MacSwiney household of this era was an intensely separatist household. Avidly reading the newspapers of Arthur Griffith (qv), they nevertheless rejected Griffith's dual monarchy policy. -

The 1916 Easter Rising Transformed Ireland. the Proclamation of the Irish Republic Set the Agenda for Decades to Come and Led Di

The 1916 Easter Rising transformed Ireland. The Proclamation of the Irish Republic set the agenda for decades to come and led directly to the establishment of an Chéad Dáil Éireann. The execution of 16 leaders, the internment without trial of hundreds of nationalists and British military rule ensured that the people turned to Sinn Féin. In 1917 republican by-election victories, the death on hunger strike of Thomas Ashe and the adoption of the Republic as the objective of a reorganised Sinn Féin changed the course of Irish history. 1916-1917 Pádraig Pearse Ruins of the GPO 1916 James Connolly Detainees are marched to prison after Easter Rising, Thomas Ashe lying in state in Mater Hospital, Dublin, Roger Casement on trial in London over 1800 were rounded up September 1917 Liberty Hall, May 1917, first anniversary of Connolly’s Crowds welcome republican prisoners home from Tipperary IRA Flying Column execution England 1917 Released prisoners welcomed in Dublin 1918 Funeral of Thomas Ashe, September 1917 The British government attempted to impose Conscription on Ireland in 1918. They were met with a united national campaign, culminating in a General Strike and the signing of the anti-Conscription pledge by hundreds of thousands of people. In the General Election of December 1918 Sinn Féin 1918 triumphed, winning 73 of the 105 seats in Ireland. The Anti-Conscription Pledge drawn up at the The Sinn Féin General Election Manifesto which was censored by Taking the Anti-Conscription Pledge on 21 April 1919 Mansion House conference on April 18 1919 the British government when it appeared in the newspapers Campaigning in the General Election, December 1918 Constance Markievicz TD and First Dáil Minister for Labour, the first woman elected in Ireland Sinn Féin postcard 1917 Sinn Féin by-election posters for East Cavan (1918) and Kilkenny City (1917) Count Plunkett, key figure in the building of Sinn Féin 1917/1918 Joseph McGuinness, political prisoner, TD for South Longford The First Dáil Éireann assembled in the Mansion House, Dublin, on 21 January 1919. -

Hunger Strikes by Irish Republicans, 1916-1923 Michael Biggs ([email protected]) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Hunger Strikes by Irish Republicans, 1916-1923 Michael Biggs ([email protected]) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Paper prepared for Workshop on Techniques of Violence in Civil War Centre for the Study of Civil War, Oslo August 2004 “It is not those who can inflict the most, but those who can suffer the most who will conquer.” (Terence MacSwiney, 1920) “The country has not had, as yet, sufficient voluntary sacrifice and suffering[,] and not until suffering fructuates will she get back her real soul.” (Ernie O’Malley, 1923) The hunger strike is a strange technique of civil war. Physical suffering—possibly even death—is inflicted on oneself, rather than on the opponent. The technique can be conceived as a paradoxical inversion of hostage-taking or kidnapping, analyzed by Elster (2004). With kidnapping, A threatens to kill a victim B in order to force concessions from the target C; sometimes the victim is also the target. With a hunger strike, the perpetrator is the victim: A threatens to kill A in order to force concessions.1 Kidnappings staged for publicity, where the victim is released unconditionally, are analogous to hunger strikes where the duration is explicitly 1 This brings to mind a scene in the film Blazing Saddles. A black man, newly appointed sheriff, is surrounded by an angry mob intent on lynching him. He draws his revolver and points it to his head, warning them not to move “or the nigger gets it.” This threat allows him to escape. The scene is funny because of the apparent paradox of threatening to kill oneself, and yet that is exactly what hunger strikers do. -

Terence Macswiney Died in Brixton Prison on 25 October on the Seventy-Fourth Day of His Hunger Strike

MacSwiney, Terence James by Patrick Maume MacSwiney, Terence James (1879–1920), republican, was born at 23 North Main Street, Cork, on 28 March 1879, son of John MacSwiney and his wife, Mary (née Wilkinson), an English catholic. John MacSwiney, a native Irish-speaker from Ballingeary, Co. Cork, had been a schoolteacher in London before starting a tobacco factory in Cork, which failed shortly before Terence’s birth. In 1885 John MacSwiney emigrated alone to Australia, where he died about 1895. His wife raised their eight surviving children, helped by her eldest daughter, Mary MacSwiney (qv). Terence was educated at the Christian Brothers' North Monastery School in Cork; he won three intermediate exhibitions, but at fifteen had to leave to become a clerk with a local firm. MacSwiney hated the restrictions of his job and hoped to attain professional status, in pursuit of which, from 1898, he began intensive study, restricting himself to six hours' sleep a night. He matriculated at the RUI in 1899 and attended QCC, graduating BA (RUI) in mental and moral science in 1907. He subsequently became a part-time lecturer in business methods at Cork Municipal School of Commerce, and in 1912 full-time travelling commercial instructor for Cork technical instruction committee. In 1899 he co-founded the separatist Celtic Literary Society (CLS). He concealed stresses and fears under a good-humoured exterior, and was respected for his commitment to everything he undertook, though some saw him as self-righteous. His political role model was William Rooney (qv), who worked himself to death at the age of twenty-nine. -

Blackpool Village Regeneration Strategy

Commissioned Study for Respond! Housing Association 2013-2014 Blackpool Village Regeneration Strategy EDUCATION REPORT February 2014 Respond! is Ireland’s leading housing who have lived for long periods in hostels, Respond! employ over 300 people who association, established in 1982. Respond! temporary and insecure accommodation. work creatively within a framework believe in delivering housing for social of shared values and social goals. The investment rather than for financial profit Respond! seek to create positive futures for in-house team is spread throughout and provide housing for almost 20,000 people by alleviating poverty and creating the country and includes architects, residents around Ireland. Homes are vibrant, socially integrated communities. accountants, technical services officers, provided for individuals, families, This is achieved by providing access psychologists, nurses, as well as the elderly, people who are living with a to education, childcare, community educational, research, finance, legal disability and also for some of the most development programmes, housing and administrative, IT, childcare and resident vulnerable groups in society including those other supports. support personnel. Copyright: Respond! Housing Association 2014 All rights reserved. First published by: Respond! Housing Association, Airmount, Dominick Place, Waterford Lo-call: 0818 357901 Web: www.respond.ie E-mail: [email protected] Respond! Housing Association is a company limited by guarantee and registered in Dublin, Ireland. Registration number 90576. Respond! comply with the Governance code for community, voluntary and charitable organisations in Ireland. Charity number CHY 6629. Registered office: Airmount, Dominick Place, Waterford, Ireland. Directors: Joe Horan (Chairman) Michael O’Doherty, Tom Dilleen, Brian Hennebry, Deirdre Keogh and Patrick Cogan, ofm. -

ROINN COSANTA BUREAU of MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT by WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 637 Witness Mrs. Muriel Mcswiney

ROINN COSANTA BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 637 Witness Mrs. Muriel McSwiney, c/o National city Bank, College Green, Dublin; 78 Rue Blomet, Paris 15. Identity. Widow of Terence McSwiney. Subject. (a) Events of national interest, 1915-1921; (b) Biographical note on Terence McSwiney. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.1634 FormB.S.M.2 Rd 43 Westbury C O London No 12 10.51 & Siycad & Cape del Cape with the accumulation of Do years, besides current lock. coring Jam to Dublin for a few days thus coring Dick & Well ring yon. I thought it best to type dome of then account it as is Clearer. 2w by Day by op 2 vip 1/3 cu by bedy ufl C Sviley Man pointeth I met mrs ten mc scoring in the stile and the promised ld come in she said she was grinding only a few here. did not days She smartly in STATEMENT BY MRS. MURIEL MOSWINEY, c/o National City Bank, College Green, Dublin. two These See typed ne McSwiney pages Mrs The first national occasion at which I was present was by memory of the Manchester Martyrs at a public meeting in the of 1915. of Grand Parade in Cork in the autumn I was, sigh fain movement before that. course, interested in the national In 1914 after the outbreak of the world war I answered a call for girls to train as nurses at the South Infirmary, soldiers. as I Cork, to nurse wounded I realised, young was, that the need for nurses would be great as the war was cause eriniurelly appalling suffering of bound to It was not that I had any as on child Whom turner bated romantic interest in soldiers, as young girls often have. -

COMHAIRLE CATHRACH CHORCAÍ CORK CITY COUNCIL 14Th February 2019 REPORT on WARD FUNDS PAID in 2018 the Following Is a List of P

COMHAIRLE CATHRACH CHORCAÍ CORK CITY COUNCIL 14th February 2019 REPORT ON WARD FUNDS PAID IN 2018 The following is a list of payees who received Ward Funds from Members in 2018: Payee Amount 37TH CORK SCOUT GROUP €500.00 38TH/40TH BALLINLOUGH SCOUT GR €750.00 3RD CORK SCOUTS TROOP €800.00 43RD/70TH CORK BISHOPSTOWN SCO €150.00 53RD CORK SCOUT TROOP €500.00 5TH CORK LOUGH SCOUTS €275.00 87TH SCOUT GROUP €100.00 AGE ACTION IRELAND €500.00 AGE LINK MAHON CDP €350.00 ARD NA LAOI RESIDENTS ASSOC €700.00 ART LIFE CULTURE LTD €100.00 ASCENSION BATON TWIRLERS €550.00 ASHDENE RES ASSOC €700.00 ASHGROVE PARK RESIDENTS ASSOCI €150.00 ASHMOUNT RESIDENTS ASSOCIATION €600.00 AVONDALE UTD F.C. €1,050.00 AVONMORE PARK RESIDENTS ASSOCI €700.00 BAILE BEAG CHILDCARE LTD €700.00 BALLINEASPIG,FIRGROVE,WESTGATE €400.00 BALLINLOUGH COMM. MIDSUMMER FE €1,300.00 BALLINLOUGH MEALS ON WHEELS €150.00 BALLINLOUGH PITCH AND PUTT CLU €200.00 BALLINLOUGH RETIRED PEOPLE'S N €100.00 BALLINLOUGH RETIREMENT CLUB €200.00 BALLINLOUGH SCOUT GROUP €600.00 BALLINLOUGH SUMMER SCHEME €1,450.00 BALLINLOUGH YOUTH CLUB €400.00 BALLINURE GAA CLUB €300.00 BALLYPHEHANE COMMUNITY ASSOC €500.00 BALLYPHEHANE COMMUNITY YOUTH E €300.00 BALLYPHEHANE DISTRICT PIPE BAN €400.00 BALLYPHEHANE GAA CLUB €800.00 BALLYPHEHANE GAA CLUB JUNIOR S €100.00 BALLYPHEHANE HURLING & FOOTBAL €500.00 BALLYPHEHANE LADIES CLUB €125.00 BALLYPHEHANE LADIES FOOTBALL C €1,250.00 BALLYPHEHANE MEALS ON WHEELS €250.00 BALLYPHEHANE MENS SHED €1,475.00 BALLYPHEHANE PIPE BAND €250.00 BALLYPHEHANE TOGHER CDP €150.00 BALLYPHEHANE -

Richard Mulcahy Papers P7

Richard Mulcahy Papers P7 UCD Archives archives @ucd.ie www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 1975 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii Introduction ix Extracts from notes by Richard Mulcahy on his papers xii RICHARD MULCAHY PAPERS A. FIRST AND SECOND DÁIL ÉIREANN, 1919-22 iv B. THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT AND v GENESIS OF THE IRISH FREE STATE, 1922-24 C. CUMANN NA NGAEDHEAL AND FINE GAEL, 1924-60 vii D. WRITINGS ON IRISH HISTORY AND LANGUAGE viii E. PERSONAL MATERIAL viii iii A. FIRST AND SECOND DÁIL ÉIREANN, 1919-22 I. Michael Collins, Minister for Finance a. Correspondence 1 b. Memoranda and Ministerial Reports 2 II. Richard Mulcahy, Chief of Staff, I.R.A. and Minister for National Defence i. Chief of Staff, I.R.A. a. Correspondence with Brigade O/Cs 3 b. Reports 6 c. Correspondence and memoranda relating to 6 defence matters d. Orders and directives 7 e. Statements 7 f. Newspapers cuttings and press extracts 7 ii. Minister for National defence a. Orders of the day, motions and agendas 8 b. Memoranda 9 c. Elections 9 d. Conference on Ireland, London 1921 9 e. Mansion House Conference 10 iii. Societies, the Arts and the Irish Language 10 iv. Dissociated material 10 iv B. THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT AND GENESIS OF THE IRISH FREE STATE, 1922-24 I. Michael Collins, Commander in Chief, I.R.A. and Free State Army a. Correspondence with General Headquarters 11 Staff b. Correspondence with Commanding Officers 12 c. Correspondence and reports on railway and 13 postal services d. -

NCSE 13/14 Full List of Special Classes Attached to Mainstream Schools

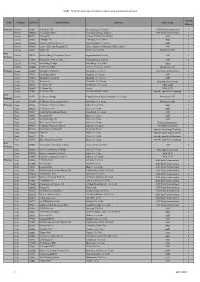

NCSE 13/14 full list of special classes attached to mainstream schools No of Type County Roll No School Name Address Class Type Classes Primary Carlow 13105L St Brigid's NS Muinebeag, Co Carlow ASD Early Intervention 2 Carlow 18424G St. Joseph’s BNS St. Joseph’s Road, Carlow ASD Early Intervention 2 Carlow 04077I Grange NS Grange, Tullow, Co Carlow ASD 2 Carlow 17514C Clonegal NS Clonegal, Co Carlow ASD 1 Carlow 18183K Queen of the Universe NS Muinebheag, Co Carlow ASD 2 Carlow 20295K Carlow Educate Together NS Unit 5, Shamrock Business Park, Carlow ASD 2 Carlow 14837L Ballon NS Ballon, Co Carlow Moderate GLD 1 Post Carlow 70430U Muine Bheag Vocational School Bagenalstown Carlow ASD 1 Primary Carlow 61150N Presentation De La Salle Bagenalstown, Carlow ASD 2 Carlow 61130H Knockbeg College Knockbeg, Co Carlow ASD 1 Carlow 61141K St Leo's College Carlow Town, Co Carlow Moderate GLD 1 Primary Cavan 19008V Mullagh Central NS Mullagh, Co. Cavan ASD Early Intervention 1 Cavan 17625L Knocktemple NS Virginia, Co Cavan ASD 3 Cavan 19008V Mullagh Central NS Mullagh, Co. Cavan ASD 1 Cavan 12312L Darley NS Cootehill, Co Cavan Hearing Impairment 1 Cavan 18059J St Annes NS Bailieboro, Co Cavan Mild GLD 1 Cavan 08490N St Clares NS Cavan Mild GLD 1 Cavan 17326B St. Felim's NS Farnham Street, Cavan Specific Speech & Language 2 Post Cavan 61051L St Clares College Virginia Road, Ballyjamesduff, Co Cavan Moderate GLD 1 Primary Cavan 70350W St. Bricin's Vocational School Belturbet, Co Cavan Moderate GLD 1 Primary Clare 20041C St Senan's Primary School Kilrush, -

A Short History of the War of Independence

Unit 6: The War of Independence 1919-1921 A Short History Resources for Secondary Schools UNIT 7: THE IRISH WAR OF INDEPENDENCE PHASE I: JAN 1919 - MARCH 1920 police boycott The first phase of the War of Independence consisted Eamon de Valera escaped from Lincoln Jail on 3 mainly of isolated incidents between the IRA and the February 1919 and when the remaining ‘German Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). From the beginning Plot’ prisoners were released in March 1919, the of the conflict, the British government refused to President of the Dáil was able to return to Ireland recognise the Irish Republic or to admit that a state without danger of arrest. He presided at a meeting of of war existed between this republic and the UK. The Dáil Éireann on 10 April 1919 at which the assembly violence in Ireland was described as ‘disorder’ and the confirmed a policy of boycotting against the RIC. IRA was a ‘murder gang’ of terrorists and assassins. For this reason, it was the job of the police rather than The RIC are “spies in our midst … the eyes and the 50,000-strong British army garrison in Ireland ears of the enemy ... They must be shown and to deal with the challenge to the authority of the made to feel how base are the functions they British administration. British soldiers would later perform and how vile is the position they become heavily involved in the conflict, but from the occupy”. beginning the police force was at the front line of the - Eamon de Valera (Dáil Debates, vol. -

Contae Corcaigh/County Cork

Online Irish History Course Contae Corcaigh/County Cork Thursdays 6 – 7:30 pm / March 4, 11, 18 & 25, 2021 Famous people from Kerry include: Michael Collins, Mother Jones, Saint Finbarr, Richard “Boss” Croker, George Boole, Annie Moore, Henry Ford, Rory Gallagher, Sonia O’Sullivan, Una Palliser, Christy Ring, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, Jack Doyle, Sam Maguire, Niall Toibin, Seán Ó Faoláin, Sarah Greene. Drombeg Stone Circle, Cork GOUGANE BARRA CHURCH Gilbert mac Turgar, the last According to local folklore the first foot was planted on Irish soil at Dún na leader of the Hiberno-Viking mBarc (the place of the boat) on the shores of Bantry Bay in 2680 BC. community in Cork, was killed The Corcu Loígde, meaning Gens of the Calf Goddess, were a kingdom by English freebooters in 1173. centered in West County Cork who descended from the proto-historical rulers of Munster, the Dáirine, of whom they were the central royal sept. Cork city was originally a monastic settlement founded by Saint Finbarr in the 6th century. Vikings attacked the monastery there in 820. Keyser’s Hill, leading to the south bank of the Lee, close to the South Gate Bridge—is the only place in Cork that still has a Viking name. The town of Baltimore was depopulated in 1631 in a slave capture raid by Barbary pirates from either Algeria or Salé (Morocco). In 1446, Cormac MacCarthy, On 26 June 1644 Lord Inchiquin decreed the expulsion of the Irish and Lord of Muskerry, built Blarney Catholic population of Cork from the city. Castle. An earlier Cormac Fastnet Rock is known as "Ireland's Teardrop” because it was the last part MacCarthy supplied 4,000 men of Ireland that 19th century Irish emigrants saw as they sailed away.