A Fence Around Jerusalem the Construction of the Security Fence Around Jerusalem General Background and Implications for the City and Its Metropolitan Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEPS Middle East & Euro-Med Project

CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY WORKING PAPER NO. 9 STUDIES JUNE 2003 Searching for Solutions THE NEW WALLS AND FENCES: CONSEQUENCES FOR ISRAEL AND PALESTINE GERSHON BASKIN WITH SHARON ROSENBERG This Working Paper is published by the CEPS Middle East and Euro-Med Project. The project addresses issues of policy and strategy of the European Union in relation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the wider issues of EU relations with the countries of the Barcelona Process and the Arab world. Participants in the project include independent experts from the region and the European Union, as well as a core team at CEPS in Brussels led by Michael Emerson and Nathalie Tocci. Support for the project is gratefully acknowledged from: • Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino • Department for International Development (DFID), London. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed are attributable only to the author in a personal capacity and not to any institution with which he is associated. ISBN 92-9079-436-4 Available for free downloading from the CEPS website (http://www.ceps.be) CEPS Middle East & Euro-Med Project Copyright 2003, CEPS Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1 • B-1000 Brussels • Tel: (32.2) 229.39.11 • Fax: (32.2) 219.41.41 e-mail: [email protected] • website: http://www.ceps.be THE NEW WALLS AND FENCES – CONSEQUENCES FOR ISRAEL AND PALESTINE WORKING PAPER NO. 9 OF THE CEPS MIDDLE EAST & EURO-MED PROJECT * GERSHON BASKIN WITH ** SHARON ROSENBERG ABSTRACT ood fences make good neighbours’ wrote the poet Robert Frost. Israel and Palestine are certainly not good neighbours and the question that arises is will a ‘G fence between Israel and Palestine turn them into ‘good neighbours’. -

Holy Land! Please Consider Departing: Coming on This “Journey of a Lifetime”

JOIN US for a Trip of a Lifetime HOSTED BY: YOUR Fr. Ray McHenry Host IMPORTANT INFORMATION Parishioners of St. Francis, We are going to the Holy Land! Please consider Departing: coming on this “Journey of a Lifetime”. I know, from $ my experience, that you will not be disappointed. OCTOBER 11, 2020 Deposit - 300 from Des Moines, IA (DSM) (upon booking) To be in the very places where Jesus lived, taught, suffered, died, and rose from the dead, is a privilege beyond description. The $ .00 2nd Payment Due: Bible will come alive for you. You will never read it or hear it proclaimed in the 4,498 MAY 14, 2020 same way once you’ve traveled to the Holy Land. Places in the Bible will not be just names on the page, but will be real. All Inclusive! Full Payment Due: The Holy Land is sometimes called the fifth Gospel because it helps us (except lunches) JULY 28, 2020 understand the other four Gospels better. I have visited the Holy Land before and look forward to returning. I have more to learn about this holy place and our Early Bird Special Each tour member must hold a salvation story. Consider joining me on this journey; you will not regret it. $100.00 off if deposit is made passport that is valid until at least by December 1, 2019 APRIL 15, 2021 I look forward to leading this group and sharing with you the joy of DAY PILGRIMAGE Application forms are available traveling and living our faith. at your local Passport Office. -

Israel-Hizbullah Conflict: Victims of Rocket Attacks and IDF Casualties July-Aug 2006

My MFA MFA Terrorism Terror from Lebanon Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket attacks and IDF casualties July-Aug 2006 Search Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket E-mail to a friend attacks and IDF casualties Print the article 12 Jul 2006 Add to my bookmarks July-August 2006 Since July 12, 43 Israeli civilians and 118 IDF soldiers have See also MFA newsletter been killed. Hizbullah attacks northern Israel and Israel's response About the Ministry (Note: The figure for civilians includes four who died of heart attacks during rocket attacks.) MFA events Foreign Relations Facts About Israel July 12, 2006 Government - Killed in IDF patrol jeeps: Jerusalem-Capital Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Eyal Benin, 22, of Beersheba Treaties Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Shani Turgeman, 24, of Beit Shean History of Israel Sgt.-Maj. Wassim Nazal, 26, of Yanuah Peace Process - Tank crew hit by mine in Lebanon: Terrorism St.-Sgt. Alexei Kushnirski, 21, of Nes Ziona Anti-Semitism/Holocaust St.-Sgt. Yaniv Bar-on, 20, of Maccabim Israel beyond politics Sgt. Gadi Mosayev, 20, of Akko Sgt. Shlomi Yirmiyahu, 20, of Rishon Lezion Int'l development MFA Publications - Killed trying to retrieve tank crew: Our Bookmarks Sgt. Nimrod Cohen, 19, of Mitzpe Shalem News Archive MFA Library Eyal Benin Shani Turgeman Wassim Nazal Nimrod Cohen Alexei Kushnirski Yaniv Bar-on Gadi Mosayev Shlomi Yirmiyahu July 13, 2006 Two Israelis were killed by Katyusha rockets fired by Hizbullah: Monica Seidman (Lehrer), 40, of Nahariya was killed in her home; Nitzo Rubin, 33, of Safed, was killed while on his way to visit his children. -

Arrested Development: the Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank

B’TSELEM - The Israeli Information Center for ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT Human Rights in the Occupied Territories 8 Hata’asiya St., Talpiot P.O. Box 53132 Jerusalem 91531 The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Tel. (972) 2-6735599 | Fax (972) 2-6749111 Barrier in the West Bank www.btselem.org | [email protected] October 2012 Arrested Development: The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank October 2012 Research and writing Eyal Hareuveni Editing Yael Stein Data coordination 'Abd al-Karim Sa'adi, Iyad Hadad, Atef Abu a-Rub, Salma a-Deb’i, ‘Amer ‘Aruri & Kareem Jubran Translation Deb Reich Processing geographical data Shai Efrati Cover Abandoned buildings near the barrier in the town of Bir Nabala, 24 September 2012. Photo Anne Paq, activestills.org B’Tselem would like to thank Jann Böddeling for his help in gathering material and analyzing the economic impact of the Separation Barrier; Nir Shalev and Alon Cohen- Lifshitz from Bimkom; Stefan Ziegler and Nicole Harari from UNRWA; and B’Tselem Reports Committee member Prof. Oren Yiftachel. ISBN 978-965-7613-00-9 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 5 Part I The Barrier – A Temporary Security Measure? ................. 7 Part II Data ....................................................................... 13 Maps and Photographs ............................................................... 17 Part III The “Seam Zone” and the Permit Regime ..................... 25 Part IV Case Studies ............................................................ 43 Part V Violations of Palestinians’ Human Rights due to the Separation Barrier ..................................................... 63 Conclusions................................................................................ 69 Appendix A List of settlements, unauthorized outposts and industrial parks on the “Israeli” side of the Separation Barrier .................. 71 Appendix B Response from Israel's Ministry of Justice ....................... -

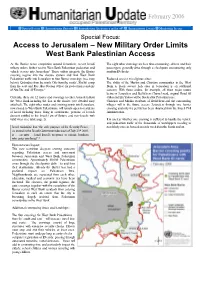

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs LEBANON SYRIA West Bank Barrier Route Projections July 2009 West Bank Gaza Strip JORDAN Barta'a ISRAEL ¥ EGYPT Area Affected r The Barrier’s total length is 709 km, more than e v i twice the length of the 1949 Armistice Line R n (Green Line) between the West Bank and Israel. W e s t B a n k a d r o The total area located between the Barrier J and the Green Line is 9.5 % of the West Bank, Qalqilya including East Jerusalem and No Man's Land. Qedumim Finger When completed, approximately 15% of the Barrier will be constructed on the Green Line or in Israel with 85 % inside the West Bank. Biddya Area Populations Affected Ari’el Finger If the Barrier is completed based on the current route: Az Zawiya Approximately 35,000 Palestinians holding Enclave West Bank ID cards in 34 communities will be located between the Barrier and the Green Line. The majority of Palestinians with East Kafr Aqab Jerusalem ID cards will reside between the Barrier and the Green Line. However, Bir Nabala Enclave Biddu Palestinian communities inside the current Area Shu'fat Camp municipal boundary, Kafr Aqab and Shu'fat No Man's Land Camp, are separated from East Jerusalem by the Barrier. Ma’ale Green Line Adumim Settlement Jerusalem Bloc Approximately 125,000 Palestinians will be surrounded by the Barrier on three sides. These comprise 28 communities; the Biddya and Biddu areas, and the city of Qalqilya. ISRAEL Approximately 26,000 Palestinians in 8 Gush a communities in the Az Zawiya and Bir Nabala Etzion e Enclaves will be surrounded on four sides Settlement S Bloc by the Barrier, with a tunnel or road d connection to the rest of the West Bank. -

Federal Register Volume 32 • Number 119

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 32 • NUMBER 119 Wednesday, June 21,1967 • Washington, D.C. Pages 8789-8845 Agencies in this issue— Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service Agriculture Department Atomic Energy Commission Business and Defense Services Administration Civil Aeronautics Board Consumer and Marketing Service Fédéral Aviation Administration Federal Communications Commission Federal Highway Administration Federal Home Loan Bank Board Federal Maritime Commission Food and Drug Administration Geological Survey Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau Navy Department Securities and Exchange Commission Small Business Administration Detailed list o f Contents appears inside. Subscriptions Now Being Accepted SLIP LAWS 90th Congress, 1st Session 1967 Separate prints of Public Laws, published immediately after enactment, with marginal annotations and legislative history references. Subscription Price: $12.00 per Session Published by Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 ¿vONAt.*- r r i i r O M l W SW D E P IC T E D Published daily, Tuesday through Saturday (no publication on Sundays, Mondays, or r r J l E i l r l I l i E l l I ^ I E l f on the day after an official Federal holiday), by the Office of the Federal Register, National $ Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration (mail address Nations Area Code 202 ^ Phone 962-8626 Archives Building, Washington, D.C. 20408), pursuant to the authority contained in the Federal Register Act, approved July 26, 1935 (49 Stat. 500, as amended; 44 U.S.C., Ch. -

Parries Hanna

637 Parries Hanna Horvitz & Horvitz Book & Nwsppr Agcy Leitner Benjamin Hadar Ins Co Ltd Mossenson Zipora & Amos Ricss Shalom (near Egged Bus Stn) . .70 97 Derech Karkur 74 83 56 Talmei Elazar 73 82 5 Shikun Rassco 72 26 Rifer Hana & Yehoshua Hospital Neve Shalvah Ltd 70 58 Lcnshitzki Shelomo Butchershop.. .72 67 Motro Samuel Car Dealer Rehov Harishonim Karkur 74 33 Levi Hermann & Lucie Rehov Harishonim 74 69 Robeosohn Dr Friedrich Rehov Ha'atzmaut Karkur 73 51 Mozes Walter Farmer Shekhunat Meged 70 30 Levit Abraham Devora & Thiya Rehov Habotnim 71 93 Robinson Abraham Derech Hanadiv71 18 Invalids Home Tel Alon Karkur 73 94 Mueller Sbelomit Rehov Hadekalim .70 34 Roichman Bros (Shomron) Ltd (near Meged) 72 83 Mahzevet Iron 74 43 Inwald F A Rehov Hanassi 73 95 Levy Otto Farmer Rehov Habotnim .72 09 Rosenau Chana Rehov Habotnim .74 79 Inwentash Josef Metal Wks Levy Tclma & Gad N Rosenbaum Dr Julius Phys Rehov Harishonim 74 36 Shechunat Rassco 21 74 24 Nachimovic Hava & Lipa Gan Hashomron 71 75 Iron Co-op Bakery Ltd Karkur .. .70 72 Lewi David Pension Kefar Pines . .73 40 Rehov Hapalmah 73 61 Rotenberg Abraham Agric Machs Lewin Ernst Jehuda Ishaky Dov Fuel & Lubr Stn Nadaf Rashid Mussa Farmer Moshav Talmei Elazar 71 12 Shekhunat Meged 72 56 Shikun Ammami 23 Karkur 73 29 Baqa El Gharbiya 71 53 Rubinstein Ami-Netzah Bet Olim D' .72 58 Liptscher Katricl & Menahem Crpntry Itin Shoshana & Ben-Zion Nattel Jacob Agcy of Carmei Oriental Rubinstein Hayim Derech Hanadiv . .71 50 Rehov Gilad 71 89 Rehov Hadekalim 70 94 Wines & Nesher Beer Lishkat Hammas Karkur 72 94 Itzkovits Aharon Car Elecn Rehov Haharuvim 72 69 S Pardes Hanna Rehov Hadkalim .70 73 Main Rd 74'40 Neumann Miriam & Kurt Local Council Baqa El Gharbiya 72 23 Sachs Dr Yehuda Gan Hashomron. -

The Israeli Experience in Lebanon, 1982-1985

THE ISRAELI EXPERIENCE IN LEBANON, 1982-1985 Major George C. Solley Marine Corps Command and Staff College Marine Corps Development and Education Command Quantico, Virginia 10 May 1987 ABSTRACT Author: Solley, George C., Major, USMC Title: Israel's Lebanon War, 1982-1985 Date: 16 February 1987 On 6 June 1982, the armed forces of Israel invaded Lebanon in a campaign which, although initially perceived as limited in purpose, scope, and duration, would become the longest and most controversial military action in Israel's history. Operation Peace for Galilee was launched to meet five national strategy goals: (1) eliminate the PLO threat to Israel's northern border; (2) destroy the PLO infrastructure in Lebanon; (3) remove Syrian military presence in the Bekaa Valley and reduce its influence in Lebanon; (4) create a stable Lebanese government; and (5) therefore strengthen Israel's position in the West Bank. This study examines Israel's experience in Lebanon from the growth of a significant PLO threat during the 1970's to the present, concentrating on the events from the initial Israeli invasion in June 1982 to the completion of the withdrawal in June 1985. In doing so, the study pays particular attention to three aspects of the war: military operations, strategic goals, and overall results. The examination of the Lebanon War lends itself to division into three parts. Part One recounts the background necessary for an understanding of the war's context -- the growth of PLO power in Lebanon, the internal power struggle in Lebanon during the long and continuing civil war, and Israeli involvement in Lebanon prior to 1982. -

Agellan Commercial Real Estate Investment Trust Annual Information

AGELLAN COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT TRUST ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2017 March 29, 2018 Table of Contents GLOSSARY OF TERMS .................................................................................................................................... 3 CERTAIN REFERENCES AND FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS .................................................................. 7 NON‐IFRS FINANCIAL MEASURES ................................................................................................................. 8 LEGAL STRUCTURE OF AGELLAN ................................................................................................................. 10 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS .............................................................................................. 12 Three Year History ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Description of the Business ....................................................................................................................... 14 THE REAL ESTATE PORTFOLIO ..................................................................................................................... 18 Occupancy and Leasing ............................................................................................................................. 18 Geographic Diversification ....................................................................................................................... -

![Thru the Bible: the Raising of Lazarus [John 11]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9366/thru-the-bible-the-raising-of-lazarus-john-11-689366.webp)

Thru the Bible: the Raising of Lazarus [John 11]

Thru the Bible: The Raising of Lazarus [John 11] Introduction (John 11:1-57): The story of the raising of Lazarus is the final and climactic “sign” in the first half of the Gospel (“Book of Signs”) and contains the fifth “I am” statement, “I am the resurrection and the life” (11:25). After this story, Jesus’ public ministry is completed, with no further public discourses. From now on, John the gospel writer will focus on the culminating events and private teaching of Jesus’ final week, leading up to his third and final Passover Festival in Jerusalem. While the Synoptic Gospels include the raising of Jairus’ daughter (Mt. and Mk.) and the widow of Nain’s son (Lk.), only John records this astonishing story of Jesus raising someone already entombed for four days. Jesus and the Bethany Family (11:1-6): The sisters Mary and Martha appear to be known to the readers, perhaps from the story in Luke 10:38-42 of Jesus teaching in their home, but their brother Lazarus is only mentioned in John’s Gospel. This family appears to be very special to Jesus, and their home in Bethany (near Jerusalem) may have been a regular place of hospitality for Jesus and his disciples when in the region. Leading up to our chapter, in 10:40-42, John tells us that when Jesus heard the news of Lazarus’ illness, he was teaching across the Jordan River, in the place where John the Baptist had been preaching, which is identified as a different Bethany in John 1:28.