Rutland Record No. 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Father of the House Sarah Priddy

BRIEFING PAPER Number 06399, 17 December 2019 By Richard Kelly Father of the House Sarah Priddy Inside: 1. Seniority of Members 2. History www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 06399, 17 December 2019 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Seniority of Members 4 1.1 Determining seniority 4 Examples 4 1.2 Duties of the Father of the House 5 1.3 Baby of the House 5 2. History 6 2.1 Origin of the term 6 2.2 Early usage 6 2.3 Fathers of the House 7 2.4 Previous qualifications 7 2.5 Possible elections for Father of the House 8 Appendix: Fathers of the House, since 1901 9 3 Father of the House Summary The Father of the House is a title that is by tradition bestowed on the senior Member of the House, which is nowadays held to be the Member who has the longest unbroken service in the Commons. The Father of the House in the current (2019) Parliament is Sir Peter Bottomley, who was first elected to the House in a by-election in 1975. Under Standing Order No 1, as long as the Father of the House is not a Minister, he takes the Chair when the House elects a Speaker. He has no other formal duties. There is evidence of the title having been used in the 18th century. However, the origin of the term is not clear and it is likely that different qualifications were used in the past. The Father of the House is not necessarily the oldest Member. -

Ketton Village Walk September 2010 (Updated 2020)

Rutland Local History & Record Society Registered Charity No. 700273 Ketton Village Walk September 2010 (updated 2020) Copyright © Rutland Local History and Record Society All rights reserved INTRODUCTION The centre of the village contains many excellent buildings constructed with the famous butter‑coloured Ketton limestone which has been quarried locally since the Middle Ages. Ketton limestone is a 'freestone' because it can be worked in any direction. It is regarded as the perfect example of oolitic limestone. Many of the stone buildings are roofed in Collyweston slates. These frost-split slates have been extracted from shallow mines at Collyweston and Easton on the Hill just The Priory about 1925. (Jack Hart Collection) across the Valley from Ketton. This walk has been prepared from notes left by the late Geoff Fox and the late Jeffrey Smith, with some additions. THE VILLAGE MAP The map attached to this guided walk is based on the 25 inch to one mile Ordnance Survey 2nd edition map of 1899. Consequently, later buildings, extensions and demolitions are not shown. Numbers in the text, e.g. [12], refer to locations shown on the maps. Please: Respect private property. Use pavements and footpaths where available. Take great care when crossing roads. The church lychgate about 1925. (Jack Hart Collection) Remember that you are responsible for your own safety. The lychgate, of English oak and roofed with Collyweston slates, was erected by George Hibbins, THE WALK stonemason of Ketton, in 1909. This is a circular walk which starts and finishes at the Pass through the lychgate and walk to the Railway Inn. -

RISE up STAND out This Guide Should Cover What You Need to Know Before You Apply, but It Won’T Cover Everything About College

RISE UP STAND OUT This guide should cover what you need to know before you apply, but it won’t cover everything about College. We 2020-21 WELCOME TO know that sometimes you can’t beat speaking to a helpful member of the VIRTUAL team about your concerns. OPEN Whether you aren’t sure about your bus EVENTS STAMFORD route, where to sit and have lunch or want to meet the tutors and ask about your course, you can Live Chat, call or 14 Oct 2020 email us to get your questions answered. COLLEGE 4 Nov 2020 Remember, just because you can’t visit 25 Nov 2020 us, it doesn’t mean you can’t meet us! 20 Jan 2021 Find out more about our virtual open events on our website. Contents Our Promise To You ..............................4 Childcare ....................................................66 Careers Reference ................................. 6 Computing & IT..................................... 70 Facilities ........................................................ 8 Construction ............................................74 Life on Campus ...................................... 10 Creative Arts ...........................................80 Student Support ....................................12 Hair & Beauty ......................................... 86 Financial Support ................................. 14 Health & Social Care .......................... 90 Advice For Parents ...............................16 Media ........................................................... 94 Guide to Course Levels ......................18 Motor Vehicle ........................................ -

Unclassified Fourteenth- Century Purbeck Marble Incised Slabs

Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, No. 60 EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS This book is published with the generous assistance of The Francis Coales Charitable Trust. EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS Sally Badham and Malcolm Norris The Society of Antiquaries of London First published 1999 Dedication by In memory of Frank Allen Greenhill MA, FSA, The Society of Antiquaries of London FSA (Scot) (1896 to 1983) Burlington House Piccadilly In carrying out our study of the incised slabs and London WlV OHS related brasses from the thirteenth- and fourteenth- century London marblers' workshops, we have © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1999 drawn very heavily on Greenhill's records. His rubbings of incised slabs, mostly made in the 1920s All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, and 1930s, often show them better preserved than no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval they are now and his unpublished notes provide system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, much invaluable background information. Without transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, access to his material, our study would have been less without the prior permission of the copyright owner. complete. For this reason, we wish to dedicate this volume to Greenhill's memory. ISBN 0 854312722 ISSN 0953-7163 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the -

468 KB Adobe Acrobat Document, Opens in A

Campden & District Historical and Archæological Society Regd. Charity No. 1034379 NOTES & QUERIES NOTES & QUERIES Volume VI: No. 1 Gratis Autumn 2008 ISSN 1351-2153 Contents Page From the Editor 1 Letters to the Editor 2 Maye E. Bruce Andrew Davenport 3 Lion Cottage, Broad Campden Olivia Amphlett 6 Sir Thomas Phillipps 1792-1872: Bibliophile David Cotterell 7 Rutland & Chipping Campden: an unexplained connection Tim Clough 9 Putting their hands to the Plough, part II Margaret Fisher 13 & Pearl Mitchell Before The Guild: Rennie Mackintosh Jill Wilson 15 ‘The Finest Street Left In England’ Carol Jackson 16 Christopher Whitfield 1902-1967 John Taplin 18 From The Editor As I start to edit this issue, I have just heard of the sad and unexpected death on 26th July after a very short illness, of Felicity Ashbee, aged 95, a daughter of Charles and Janet Ashbee. Her funeral was held on 6th August and there is to be a Memorial Tribute to her on 2nd October at the Art Workers Guild in London. Felicity has been the authority on her parents’ lives for many years now and her Obituary in the Independent described her as ‘probably the last close link with the inner circle of extraordinary creative talents fostered or inspired by William Morris’ … her death ‘marks its [the Arts & Crafts movement] formal and final passing’. This first issue of Volume Number VI is a bumper issue full of connections. John Taplin, Andrew Davenport and Tim Clough (Editor of Rutland Local History & Record Society), after their initial queries to the Archive Room, all sent articles on their researches; the pieces on Maye Bruce and Thomas Phillipps are connected with new publications; there is an ‘earthy’ connection between with the Plough, Rutland and Bruce researches and the Phillipps and Whitfield articles both have Shakespeare connections. -

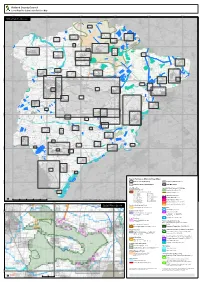

Rutland Main Map A0 Portrait

Rutland County Council Local Plan Pre-Submission Policies Map 480000 485000 490000 495000 500000 505000 Rutland County - Main map Thistleton Inset 53 Stretton (west) Clipsham Inset 51 Market Overton Inset 13 Inset 35 Teigh Inset 52 Stretton Inset 50 Barrow Greetham Inset 4 Inset 25 Cottesmore (north) 315000 Whissendine Inset 15 Inset 61 Greetham (east) Inset 26 Ashwell Cottesmore Inset 1 Inset 14 Pickworth Inset 40 Essendine Inset 20 Cottesmore (south) Inset 16 Ashwell (south) Langham Inset 2 Ryhall Exton Inset 30 Inset 45 Burley Inset 21 Inset 11 Oakham & Barleythorpe Belmesthorpe Inset 38 Little Casterton Inset 6 Rutland Water Inset 31 Inset 44 310000 Tickencote Great Inset 55 Casterton Oakham town centre & Toll Bar Inset 39 Empingham Inset 24 Whitwell Stamford North (Quarry Farm) Inset 19 Inset 62 Inset 48 Egleton Hambleton Ketton Inset 18 Inset 27 Inset 28 Braunston-in-Rutland Inset 9 Tinwell Inset 56 Brooke Inset 10 Edith Weston Inset 17 Ketton (central) Inset 29 305000 Manton Inset 34 Lyndon Inset 33 St. George's Garden Community Inset 64 North Luffenham Wing Inset 37 Inset 63 Pilton Ridlington Preston Inset 41 Inset 43 Inset 42 South Luffenham Inset 47 Belton-in-Rutland Inset 7 Ayston Inset 3 Morcott Wardley Uppingham Glaston Inset 36 Tixover Inset 60 Inset 58 Inset 23 Barrowden Inset 57 Inset 5 Uppingham town centre Inset 59 300000 Bisbrooke Inset 8 Seaton Inset 46 Eyebrook Reservoir Inset 22 Lyddington Inset 32 Stoke Dry Inset 49 Thorpe by Water Inset 54 Key to Policies on Main and Inset Maps Rutland County Boundary Adjoining -

![130 NAPIER I (Naper, Napper) [Alington, Scott, Sturt] SCOTLAND](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8180/130-napier-i-naper-napper-alington-scott-sturt-scotland-308180.webp)

130 NAPIER I (Naper, Napper) [Alington, Scott, Sturt] SCOTLAND

130 List of Parliamentary Families NAPIER I (Naper, Napper) [Alington, Scott, Sturt] SCOTLAND & ENGLAND Baron Napier and Ettrick (1627- S and 1872- UK) Origins: The founder of the family made a fortune in the wool trade. Provost of Edinburgh 1403. His son, a merchant adventurer and courtier, was Kted 1452. Began purchasing estates in the 1530s. One family member fought at Flodden and another at Pinkie. Master of the Mint 1576. First [MP 1471 for Edinburgh]. Another [MP 1463, also for Edinburgh]. 1. Alexander Napier – [Stirlingshire 1690-1700] 2. Francis Napier – [Stirling Burgh 1698-1702] 3. Sir Charles Napier – Marylebone 1841-47 Southwark 1855-60 4. Sir Joseph Napier 1 Bt – Dublin University 1848-58 5. Mark Napier – Roxburghshire 1892-95 Seats: Thirlestane Castle (House, Tower), Selkirkshire (built late 16th c., rebuilt 1816- 20, remod. 1872, demolished 1965); Merchistoun (Merchiston) (Hall), Edinburghshire (purch. and built 1436, add. 16th c., remod. 18th c., sold 1914, later a school) Estates: Bateman 6991 (S) 2316 Titles: Baronet 1627-83; 1637- ; 1867- Peers: [2 peers 1660-86] 2 Scottish Rep peers 1796-1806 1807-23 1824-32 3 peers 1872- 1945 1 Ld Lt 18th-19 th 1 KT 19th Notes: John Napier of Merchistoun invented logarithms. 1, 2, 8, 9, and 10 Barons and seventeen others in ODNB. Scott Origins: Sir William Scott 2 Bt of Thirlestane married the daughter of the 5 Baron Napier. Their son took the name Napier and inherited the Barony and Thirlestane. The Scotts were cadets of the Scotts of Harden (see Home). Granted arms 1542 and acquired estates in the first half of the 16th century. -

Leices'rershire. [KILLY's Harriman John, Market Gardener Hubbard Samuel, Royal P.H

BROVGBTON .ASTLEY. LEICEs'rERSHIRE. [KILLY'S Harriman John, market gardener Hubbard Samuel, Royal P.H. &; butcher IMartin Harriet (Mrs.), farmer Hopkins William, farmer IHunt William, farmer Tite Edmund, jobbing gardener NETHER BROUGHTON is a village and parish on of Caius College, Cambridge, and rural dean of Framland the borders of Nottinghamslure, 1~ miles north-east from third portion. A National school was built here in 1845 and Old Dalby station on the Melton and Nottingham branch of enlarged to hold 100 in 1847, by the Rev. John Noble B.A. the Midland line, 6 miles north-west from Melton Mowbray late rector, and is now used for the purposes of a Church and 121 from London by rail, in the Eastern division of the Sunday school and for parish meetings. A Wesleyan chapel county, Framland hundred, Melton Mowbray union, petty was built in 1829. Here are charities (left 1682), producing sessional division and county court district, rural deanery of about £7 yearly. There are no manorial rights. A.. Lang Framland third portion, archdeaconry of Leicester and ham esq. and Seymour Pleydell Bouverie esq. are the prin diocese of Peterborough. The church of St. Mar,V is a cipal landowners. The soIl is heavy clay; subsoil, clay. building of stone in the Gothic style of the 14th century, The chief crops are turnips, wheat, oats and barley, with a consisting of chancel, clerestoried nave of three bays, aisles lal'ge quantity of pasture. The area is 2,230 acres; rate and an embattled tower with pinnacles, containing 3 bells, able value, £4,084; in 1881 the population was 454. -

Rutland Record No. 19

No 19 (1999) Journal of the Rutland Local History & Record "Society Rutland cal isto ecord ciety The Society is formed from the union in June 1991 of the Rutland Local History Society, founded in the 1930s, and the Rutland Record Society, founded in 1979. In May 1993, the Rutland Field Research Group for Archaeology and History, founded in 1971, also amalgamated with the Society. The Society is a Registered Charity, and its aim is the advancement of the education of the public in an aspects of the history of the ancient County of Rutland and its immediate area. Registered Charity No. 700273 PRESIDENT Prince Yuri Galitzine CHAIRMAN J Field VICE-CHAIRMEN P N Lane HONORARY SECRETARY P Rayner, c/o Rutland County Museum, Oakham, Rutland HONORARY TREASURER Dr M Tillbrook, 7 Redland Road, Oakham, Rutland HONORARY MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Mrs E Clinton, c/o Rutland County Museum, Oakham, Rutland HONORARY EDITOR T H McK Clough HONORARY ARCHIVIST C Harrison, Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester & Rutland HONORARY LEGAL ADVISER J B Ervin EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE The Officers of the Society and the following elected members: M E Baines, D Carlin, Mrs S Howlett, Mrs E L Jones, Professor A Rogers, D Thompson EDITORIAL COMMITTEE ME Baines, TH McK Clough (convenor), J Field, Prince Yuri Galitzine, R P Jenkins, P N Lane, Dr M Tillbrook HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE D Carlin ARCHAEOLOGICAL COMMITTEE Chairman: Mrs EL Jones HONORARY MEMBERS Sqn Ldr A W Adams, Mrs O Adams, Miss E B Dean, B Waites Enquiries relating to the Society's activities, such as membership, editorial matters, historic buildings, or programme of events, should be addressed to the appropriate Officer of the Society. -

Annual Review 2016

nationalchurchestrust.org facebook.com/nationalchurchestrust @natchurchtrust flickr.com/photos/nationalchurchestrust vimeo.com/nationalchurchestrust Instagram.com/nationalchurchestrust You can support the work of the National Churches Trust by making a donation online at www.nationalchurchestrust.org/donate The National Churches Trust 7 Tufton Street, London SW1P 3QB Telephone: 020 7222 0605 Web: www.nationalchurchestrust.org Email [email protected] St Catherine’s church, Temple, Cornwall For people who love church buildings Published by The National Churches Trust ©2017 Company registered in England Registration number 06265201 Annual Review Registered charity number 1119845 2016 – 2017 Printed by Gemini Print Southern Ltd Designed by GADS Limited Contents Patron Chairman’s Introduction .............................................4 Her Majesty The Queen The Year in Review ........................................................5 Vice Patron HRH The Duke of Gloucester KG GCVO ARIBA Grants Programme .................................................... 14 Presidents Bill Bryson, ExploreChurches ................................. 19 The Archbishop of Canterbury The Archbishop of York Lucy Winkett, Using our church buildings ........ 22 Vice Presidents Catherine Pepinster, Joseph Hansom – Bill Bryson OBE A Victorian great ........................................................ 24 Sarah Bracher MBE Lord Cormack FSA Dr Matthew Byrne, English Parish Churches Robin Cotton MBE Huw Edwards and Chapels ................................................................ -

Ketton Conservation Area

Ketton Conservation Area Ketton Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan Draft for consultation August 2019 1 1.0 Background Ketton conservation area was designated in 1972, tightly drawn around the historic core of Church Road, Chapel Lane, Redmiles Lane, Aldgate and Station Road and extended in 1975 to its current size. 2.0 Location and Setting Ketton is a large village located 4 miles south west of Stamford on the Stamford Road (A6121). It has been identified within the Rutland Landscape Character Assessment (2003) as being within the ‘Middle Valley East’ of the ‘Welland Valley’ character area which is ‘a relatively busy, agricultural, modern landscape with many settlements and distinctive valley profiles.’ The river Chater is an important natural feature of the village and within the valley are a number of meadow areas between Aldgate and Bull Lane that contribute towards the rural character of the conservation area. The south western part of the conservation area is particularly attractive with a number of tree groups at Ketton Park, the private grounds of the Priory and The Cottage making a positive contribution. The attractive butter coloured stone typical of Ketton is an important feature of the village. The stone quarry and cement works which opened in 1928 is located to the north. A number of famous buildings have been built out of Ketton Stone, such as Burghley House and many of the Cambridge University Colleges. Although the Parish Church is of Barnack stone. The historic core is nestled in the valley bottom on the north side of the River Chater and extends in a linear form along the High Street, continuing onto Stamford Road (A6121). -

Rutland County Council Electoral Review Submission on Warding Patterns

Rutland County Council Electoral Review Submission on Warding Patterns INTRODUCTION 1. The Council presented a Submission on Council Size to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) on 11 July 2017 following approval at Full Council. On 25 July the LGBCE wrote to the Council advising that it was minded to recommend that 26 County Councillors should be elected to Rutland County Council in future in accordance with the Council’s submission. 2. The second stage of the review concerns warding arrangements. The Council size will be used to determine the average (optimum) number of Electors per councillor to be achieved across all wards of the authority. This number is reached by dividing the electorate by the number of Councillors on the authority. The LGBCE initial consultation on Warding Patterns takes place between 25 July 2017 and 2 October 2017. 3. The Constitution Review Working Group is Cross Party member group. The terms of reference for the Constitution Review Working Group (CRWG) (Agreed at Annual Council 8 May 2017) provide that the working group will review arrangements, reports and recommendations arising from Boundary and Community Governance reviews. Therefore, the CRWG undertook to develop a proposal on warding patterns which would then be presented to Full Council on 11 September 2017 for approval before submission to the LGBCE. BACKGROUND 4. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England technical guidance states that an electoral review will be required when there is a notable variance in representation across the authority. A review will be initiated when: • more than 30% of a council’s wards/divisions having an electoral imbalance of more than 10% from the average ratio for that authority; and/or • one or more wards/divisions with an electoral imbalance of more than 30%; and • the imbalance is unlikely to be corrected by foreseeable changes to the electorate within a reasonable period.