1467 MS: the Macneils”, Published in West Highland Notes & Queries, Ser

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heraldry Arms Granted to Members of the Macneil, Mcneill, Macneal, Macneile Families

Heraldry Arms granted to members of the MacNeil, McNeill, Macneal, MacNeile families The law of heraldry arms In Scotland all things armorial are governed by the laws of arms administered by the Court of the Lord Lyon. The origin of the office of Lord Lyon is shrouded in the mists of history, but various Acts of Parliament, especially those of 1592 and 1672 supplement the established authority of Lord Lyon and his brother heralds. The Lord Lyon is a great officer of state and has a dual capacity, both ministerial and judicial. In his ministerial capacity, he acts as heraldic advisor to the Sovereign, appoints messengers-at-arms, conducts national ceremony and grants arms. In his judicial role, he decides on questions of succession, authorizes the matriculation of arms, registers pedigrees, which are often used as evidence in the matter of succession to peerages, and of course judges in cases when the Procurator Fiscal prosecutes someone for the wrongful use of arms. A System of Heraldry Alexander Nisbet Published 1722 A classic standard heraldic treatise on heraldry, organized by armorial features used, and apparently attempting to list arms for every Scottish family, alive at the time or extinct. Nesbit quotes the source for most of the arms included in the treatis alongside the blazon A System of Heraldry is one of the most useful research sources for finding the armory of a Scots family. It is also the best readily available source discussing charges used in Scots heraldry . The Court of the Lord Lyon is the heraldic authority for Scotland and deals with all matters relating to Scottish Heraldry and Coats of Arms and maintains the Scottish Public Registers of Arms and Genealogies. -

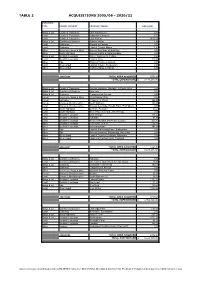

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

Argyll Bird Report with Sstematic List for the Year

ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Volume 15 (1999) PUBLISHED BY THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB Cover picture: Barnacle Geese by Margaret Staley The Fifteenth ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Edited by J.C.A. Craik Assisted by P.C. Daw Systematic List by P.C. Daw Published by the Argyll Bird Club (Scottish Charity Number SC008782) October 1999 Copyright: Argyll Bird Club Printed by Printworks Oban - ABOUT THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB The Argyll Bird Club was formed in 19x5. Its main purpose is to play an active part in the promotion of ornithology in Argyll. It is recognised by the Inland Revenue as a charity in Scotland. The Club holds two one-day meetings each year, in spring and autumn. The venue of the spring meeting is rotated between different towns, including Dunoon, Oban. LochgilpheadandTarbert.Thc autumn meeting and AGM are usually held in Invenny or another conveniently central location. The Club organises field trips for members. It also publishes the annual Argyll Bird Report and a quarterly members’ newsletter, The Eider, which includes details of club activities, reports from meetings and field trips, and feature articles by members and others, Each year the subscription entitles you to the ArgyZl Bird Report, four issues of The Eider, and free admission to the two annual meetings. There are four kinds of membership: current rates (at 1 October 1999) are: Ordinary E10; Junior (under 17) E3; Family €15; Corporate E25 Subscriptions (by cheque or standing order) are due on 1 January. Anyonejoining after 1 Octoberis covered until the end of the following year. -

Campbell." Evidently His Was a Case of an Efficient, Kindly Officer Whose Lot Was Cast in Uneventful Lines

RECORDS of CLAN CAMPBELL IN THE MILITARY SERVICE OF THE HONOURABLE EAST INDIA COMPANY 1600 - 1858 COMPILED BY MAJOR SIR DUNCAN CAMPBELL OF BARCALDINE, BT. C. V.o., F.S.A. SCOT., F.R.G.S. WITH A FOREWORD AND INDEX BY LT.-COL. SIR RICHARD C. TEMPLE, BT. ~ C.B., C.I.E., F.S.A., V.P.R,A.S. LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. 39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON, E.C. 4 NEW YORK, TORONTO> BOMBAY, CALCUTTA AND MADRAS r925 Made in Great Britain. All rights reserved. 'Dedicated by Permission TO HER- ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCESS LOUISE DUCHESS OF ARGYLL G.B.E., C.I., R.R.C. COLONEL IN CHIEF THE PRINCESS LOUISE'S ARGYLL & SUTHERLAND HIGHLANDERS THE CAMPBELLS ARE COMING The Campbells are cowing, o-ho, o-ho ! The Campbells are coming, o-ho ! The Campbells are coming to bonnie Loch leven ! The Campbells are coming, o-ho, o-ho ! Upon the Lomonds I lay, I lay ; Upon the Lomonds I lay; I lookit down to bonnie Lochleven, And saw three perches play. Great Argyle he goes before ; He makes the cannons and guns to roar ; With sound o' trumpet, pipe and drum ; The Campbells are coming, o-ho, o-ho ! The Camp bells they are a' in arms, Their loyal faith and truth to show, With banners rattling in the wind; The Campbells are coming, o-ho, o-ho ! PREFACE IN the accompanying volume I have aimed at com piling, as far as possible, complete records of Campbell Officers serving under the H.E.I.C. -

The Clan Macneil

THE CLAN MACNEIL CLANN NIALL OF SCOTLAND By THE MACNEIL OF BARRA Chief of the Clan Fellow of the Society of .Antiquarie1 of Scotland With an Introduction by THE DUKE OF ARGYLL Chief of Clan Campbell New York THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY MCMXXIII Copyright, 1923, by THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY Entered at Stationers~ Hall, London, England .All rights reser:ved Printed by The Chauncey Holt Compan}'. New York, U. 5. A. From Painting by Dr. E, F. Coriu, Paris K.1s11\1 UL CASTLE} IsLE OF BAH HA PREFACE AVING a Highlander's pride of race, it was perhaps natural that I should have been deeply H interested, as a lad, in the stirring tales and quaint legends of our ancient Clan. With maturity came the desire for dependable records of its history, and I was disappointed at finding only incomplete accounts, here and there in published works, which were at the same time often contradictory. My succession to the Chiefship, besides bringing greetings from clansmen in many lands, also brought forth their expressions of the opinion that a complete history would be most desirable, coupled with the sug gestion that, as I had considerable data on hand, I com pile it. I felt some diffidence in undertaking to write about my own family, but, believing that under these conditions it would serve a worthy purpose, I commenced this work which was interrupted by the chaos of the Great War and by my own military service. In all cases where the original sources of information exist I have consulted them, so that I believe the book is quite accurate. -

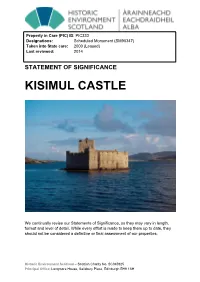

Kisimul Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC333 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90347) Taken into State care: 2000 (Leased) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KISIMUL CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KISIMUL CASTLE SYNOPSIS Kisimul Castle (Caisteal Chiosmuil) stands on a small island in Castle Bay, at the south end of the island of Barra and a short distance off-shore of the town of Castlebay. -

Clan Macneil Association of America

Clan MacNeil Association of Australia Newsletter for clan members and friends. December 2010 Editor - John McNeil 21 Laurel Avenue, Linden Park, SA 5065 telephone 08 83383858 Items is this newsletter – more information for her from Calum MacNeil, • Welcome to new members genealogist on Barra. • Births, marriages and deaths • National clan gathering in Canberra Births, Marriages and Deaths • World clan gathering on Barra Aug. On 2 nd October John McNeil married Lisa van 2010 Grinsven at the Bird in hand winery in the • News from Barra Adelaide hills • Lunch with Cliff McNeil & Bob Neil • Jean Buchanan & John Whiddon at Daylesford highland gathering • Reintroduction of beavers to Knapdale • Proposal for a clan young adult program • Recent events • Coming events • Additions to our clan library • An update of the research project of the McNeill / MacNeil families living in Argyll 1400 -1800 AD • Clan MacNeil merchandise available to you • Berneray one of the Bishop’s isles south John is the son of Peter and Mary and grandson of Barra of Ronald McNeil, my cousin. He represents the fifth generation of a John McNeil in our family. Please join with me in congratulating them on New Members their marriage. I would like to welcome our new clan members who have joined since the last newsletter. We offer our deepest sympathy to Cliff McNeil Mary Surman on the death of his mother, Helen Mary McNeil Carol & John Searcy who died on 8 th November 2010, age 96 years. Phillip Draper Helen was a member of the committee for the Clan MacNeil Association of Australia in its Over recent months I have met with John early days in Sydney. -

A Adhamhar Foltchaion, 6. Aedhan Glas, Son of N Uadhas, 4. Aefa

INDEX A Aula£ the White, King of the Danes, 22. Adhamhar Foltchaion, 6. Auldearn, Battle of, 123. Aedhan Glas, son of N uadhas, 4. Aefa, daughter of Alpin, 9. B Agnomain, 1. Agnon, Fionn, 1. Bachca (Lorne), battle at, 58. Aileach, Fortress of, 14, 15. Badhbhchadh, 5. Ailill, son of Eochaidh, 12. Baile Thangusdail (Barra), 179. Aitlin, 4. Baine, daughter of Seal Balbh, 8. Airer Gaedhil (see ARGYLL). Baliol, Edward, 40. - Aithiochta, wife of Feargal IX, 19. Bannockburn, Battle of, 40. Alba (Scotland), 13. Baoth, 1. Alexander II, King of Scotland, 38. Bar, Barony of, Kintyre, 40. Alexander III, King of Scotland, 38. Barra, origin of name, 26, 150 et Alladh, 1. seq.; Allan, son of Ruari, 39. description, 167, 174, 179 et seq.; Allan nan Sop, (see ALLAN MAC- settled by the Macneils, 24; LEAN OF GrGHA). Charters, 42, 45, 83, 99; A11en, Battle of, 19. Norse occupation, 27-32 (see Alpin, King of the Picts, 9. Norsemen) ; America, Emigration to, 90, 93, 122, under Lordship of the Isles, 39, 133 et seq., 206, 207, 210. 41; Ancrum Moor, Battle of, 100. sale of, 137; Angus Og, son of John of the Isles, brooches, 28-31; 45. religion, 145 et seq. (see MAc A11n Ja11e, wreck of the, 195. NEIL). Antigonish, settlement at, 136. "Barra Song," 25. Aodh Aonrachan, 41. "Barra Register," quoted, 25, 33. Aodh, son of Aodh Aonrachan XX, Barton, Robert, 49. 24. Baruma, The (a tax), 19. Aoife, wife of Fiacha, 10. Battle customs, 161-164. Aongus Olmucach, 4. Bealgadain, Battle of, 4. Aongus Tuirneach-Teamrach, son of Bearnera, Isle, (see Berne ray). -

Disposals 2005/06 - 2017/18

TABLE 3 DISPOSALS 2005/06 - 2017/18 DATE OF SALE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA(HA) COMPLETION Forest Cowal & Trossachs Land at Ormidale House, Glendaruel 1.40 17/10/2005 Other Cowal & Trossachs Land at Blairvaich Cottage, Loch Ard Forest 0.63 18/11/2005 Forest Galloway Craighlaw Plantation 21.00 28/04/2005 Forest Galloway Craignarget 26.66 04/05/2005 Forest Galloway Land adjacent to Aldinna Farm 0.89 17/11/2005 Other Galloway Airies Access 0.00 01/08/2005 Other Galloway Land at No.1 Craiglee Cottages, Loch Doon 0.09 22/09/2005 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye Aline Wood 629 13/05/2005 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye Tomich Service Reservoir 0.20 13/03/2006 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye Uigshader Plantation (Skye) 83.50 23/03/2006 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Plot at Keepers Croft, Glenlia 0.22 03/08/2005 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Land at Foresters House, Eynort 0.04 19/08/2005 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Land at No 1 Glenelg 0.06 05/09/2005 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Land at Old Smiddy, Laide 0.01 11/10/2005 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Glen Convinth WTW - Access Servitude 0.00 04/01/2006 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Old Schoolhouse, Glenmore 0.26 20/01/2006 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Land at Badaguish 0.80 22/02/2006 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Invermoriston Water Treatment Works 0.30 13/03/2006 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye House Plot at Inverinate (Old Garages Site). 0.16 27/03/2006 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Garve, land at Former Free Church 0.07 27/03/2006 Forest Lochaber Maol Ruadh 13.00 23/03/2006 NFLS Lochaber Strontian -

Clan Macneil Association of New Zealand

Clan MacNeil Association of New Zealand September 2009 Newsletter: Failte – Welcome Welcome to the September edition, of the Clan MacNeil newsletter. Thanks to all those who have helped contribute content— keep it up. Tartan Day Celebrations Waikato - Bay of Plenty Clan Associations cele- brated Tartan Day on The 4th July at Tauranga. The day hosted by Clan Cameron was atttended by about 100 members from Waikato, the Bay of Plenty coming from as far away as Taumaranui. Clan MacNeil attendees were Pat Duncan, Judith Bean and new member Heather Peart. ―The rain held off for a very short march from a College field across the road into the Wesley Church Hall where the function was held. After the piping in of the Banners each Clan representative was invited to speak on behalf of their Clan which I duly did passing on greetings from Clan McNeil” said MacNeil participant Pat Duncan.‖ ―Ted Little our usual representative to this function was unable to attend and sent his apologies. Clan Cameron Chief gave a short speech outlining the outlawing of The Tartan and its reinstatement” added Duncan. Clans represented were; Clan Cameron, David- son, McArthur, Wallace, Gordon, Johnston (accompanied by their little granddaughters). McLoughlan, Donnachaidh and Stewart. Jessica McLachland danced having just returned The coffee cart did a great trade in the break be- from attending Homecoming Scotland with her fore the Haggis was piped in.The Address given grandfather, Dave, who also sang a selection of and attendees all participated in a wee dram (or songs with 3 others. Attendees were all invited to juice ) to toast the Haggis. -

The Scottish Highland Regiments in the French and Indian

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1968 The cottS ish Highland Regiments in the French and Indian War Nelson Orion Westphal Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Westphal, Nelson Orion, "The cS ottish Highland Regiments in the French and Indian War" (1968). Masters Theses. 4157. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4157 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #3 To: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. Subject: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is rece1v1ng a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements. Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced -

Cowal Highland Gathering

SECRETARY’S NAME…………………………………………………………...............…. ADDRESS………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………. POST CODE ………………………….. TELNO: ………………......…… Email Address:……………………………………………………………. Second Contact Email Address:………………………………………… COWAL PIPE BAND CHAMPIONSHIP AND DRUM MAJOR COMPETITION Telephone Contact for day of Contest:…………………………………. ENTRY FEE ENCLOSED £……………… Promoted by: All cheques made payable to: COWAL HIGHLAND GATHERING The RSPBA Glasgow and West of Scotland Branch Organised by: ALL BAND AND DRUM MAJOR ENTRY FORMS AND FEES TO: THE ROYAL SCOTTISH PIPE BAND ASSOCIATION Contest Secretary: Nigel Greeves 11 Glen Grove, East Kilbride. G75 0BG GLASGOW and WEST of SCOTLAND BRANCH [email protected] Tel: 01355 242302 Mob: 07849354170 Venue: Dunoon Stadium PA23 7RL CLOSING DATE: SATURDAY 27th July 2019 Please note: SATURDAY 31th AUGUST 2019 All Drum Major entries must be received by the closing date. All trophies should be returned to: Cowal Highland Gathering – [email protected] by: Saturday 1st June 2019 COWAL PIPE BAND CHAMPIONSHIP AND DRUM MAJOR COMPETITION COWAL PIPE BAND CHAMPIONSHIP AND DRUM MAJOR COMPETITION Saturday 31st August 2019 Saturday 31st August 2019 ENTRY FORM G1 G2 G2MSR G3 G3MSR Juv G4A/NJA G4B/NJB ADM JDM BAND……………………………………………………..GRADE…………… st PIPE 1 £840 £430 £430 £420 £420 £420 £360 £360 £120 Medal nd MAJOR………................................TARTAN………....................………… 2 £740 £370 £370 £360 £360 £360 £280 £280 £100 Medal rd 3 £630 £320 £320 £300 £300 £300 £160 £160 £80 Medal Please indicate if the Band will be travelling by coach YES NO 4th £510 £260 £260 £240 £240 £240 £125 £125 £50 Medal Bus Passes Will Be Issued 5th £370 £200 £200 £180 £180 £180 £100 £100 N/A Medal 6th N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A £70 £70 N/A N/A MEDLEY ..................................................................................................................