Institutional Influence on Documentary Form: an Analysis of PBS and HBO Documentary Programs Mark Joseph Irving University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dangerous Summer

theHemingway newsletter Publication of The Hemingway Society | No. 73 | 2021 As the Pandemic Ends Yet the Wyoming/Montana Conference Remains Postponed Until Lynda M. Zwinger, editor 2022 the Hemingway Society of the Arizona Quarterly, as well as acquisitions editors Programs a Second Straight Aurora Bell (the University of Summer of Online Webinars.… South Carolina Press), James Only This Time They’re W. Long (LSU Press), and additional special guests. Designed to Confront the Friday, July 16, 1 p.m. Uncomfortable Questions. That’s EST: Teaching The Sun Also Rises, moderated by Juliet Why We’re Calling It: Conway We’ll kick off the literary discussions with a panel on Two classic posters from Hemingway’s teaching The Sun Also Rises, moderated dangerous summer suggest the spirit of ours: by recent University of Edinburgh A Dangerous the courage, skill, and grace necessary to Ph.D. alumna Juliet Conway, who has a confront the bull. (Courtesy: eBay) great piece on the novel in the current Summer Hemingway Review. Dig deep into n one of the most powerful passages has voted to offer a series of webinars four Hemingway’s Lost Generation classic. in his account of the 1959 bullfighting Fridays in a row in July and August. While Whether you’re preparing to teach it rivalry between matadors Antonio last summer’s Houseguest Hemingway or just want to revisit it with fellow IOrdóñez and Luis Miguel Dominguín, programming was a resounding success, aficionados, this session will review the Ernest Hemingway describes returning to organizers don’t want simply to repeat last publication history, reception, and major Pamplona and rediscovering the bravery year’s model. -

Nomination Press Release

Elisabeth Moss as Peggy Olson Outstanding Lead Actor In A Drama Series Nashville • ABC • ABC Studios Connie Britton as Rayna James Breaking Bad • AMC • Sony Pictures Television Scandal • ABC • ABC Studios Bryan Cranston as Walter White Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope Downton Abbey • PBS • A Carnival / Masterpiece Co-Production Hugh Bonneville as Robert, Earl of Grantham Outstanding Lead Actor In A Homeland • Showtime • Showtime Presents, Miniseries Or A Movie Teakwood Lane Productions, Cherry Pie Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Keshet, Fox 21 Weintraub Productions in association with Damian Lewis as Nicholas Brody HBO Films House Of Cards • Netflix • Michael Douglas as Liberace Donen/Fincher/Roth and Trigger Street Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Inc. in association with Media Weintraub Productions in association with Rights Capital for Netflix HBO Films Kevin Spacey as Francis Underwood Matt Damon as Scott Thorson Mad Men • AMC • Lionsgate Television The Girl • HBO • Warner Bros. Jon Hamm as Don Draper Entertainment, GmbH/Moonlighting and BBC in association with HBO Films and Wall to The Newsroom • HBO • HBO Entertainment Wall Media Jeff Daniels as Will McAvoy Toby Jones as Alfred Hitchcock Parade's End • HBO • A Mammoth Screen Production, Trademark Films, BBC Outstanding Lead Actress In A Worldwide and Lookout Point in association Drama Series with HBO Miniseries and the BBC Benedict Cumberbatch as Christopher Tietjens Bates Motel • A&E • Universal Television, Carlton Cuse Productions and Kerry Ehrin -

In the Same Breath

IN THE SAME BREATH A film by Nanfu Wang #InTheSameBreathHBO DEBUTS 2021 ON HBO SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL SCREENING SCHEDULE Thursday, January 28 at 5:00 PM PT / 6:00 PM MT – Online (WORLD PREMIERE) For press materials, please visit: ftp://ftp.homeboxoffice.com username: documr password: qq3DjpQ4 Running Time: 95 min Press Contact Press Contact HBO Documentary Films Cinetic Marketing Asheba Edghill / Hayley Hanson Rachel Allen / Ryan Werner Asheba cell: 347-721-1539 Rachel cell: 937-241-9737 Hayley cell: 201-207-7853 Ryan cell: 917-254-7653 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LOGLINE Nanfu Wang's deeply personal IN THE SAME BREATH recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. SHORT SYNOPSIS IN THE SAME BREATH, directed by Nanfu Wang (“One Child Nation”), recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. In a deeply personal approach, Wang, who was born in China and now lives in the United States, explores the parallel campaigns of misinformation waged by leadership and the devastating impact on citizens of both countries. Emotional first-hand accounts and startling, on-the-ground footage weave a revelatory picture of cover-ups and misinformation while also highlighting the strength and resilience of the healthcare workers, activists and family members who risked everything to communicate the truth. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I spent a lot of my childhood in hospitals taking care of my father, who had rheumatic heart disease. -

Hamptons Doc Fest 2020 Congratulations on 13 Years of Championing Documentary Films!

Art: Nofa Aji Zatmiko ALL DOCS ALL DAY DOCS ALL ALL OPENING NIGHT FILM: MLK/FBI Hamptons Doc Fest DECEMBER 4–13, 2020 www.hamptonsdocfest.com is a year we will long Wiseman and his newest film, City Hall. 2020 rememberWELCOME or want LETTER to He stands as one of the documentary forget. Deprived of a movie theater’s giants that every aspiring filmmaker magic we struggled to take the virtual learns from, that Wiseman way of plunge. Ultimately, we decided on yes observing life unfold. Our Award films we can to bring you our 13th festival capture the essence of Art & Music, in these overwhelming times. We Human Rights, and the Environment. programmed 35 great documentary Our Opening night film reveals a hidden films to watch in the warmth and chapter in Martin Luther King’s world. comfort of your home over 10 days. No New this year, you’ll hear and see UP worries about weather, parking, ticket CLOSE video clips presented by the lines, where to catch a snack between Directors of each film. My thanks to an films. You can schedule your own day extraordinary team, and to our Artistic the way you like it. Consider it not Director, Karen Arikian. Lastly, you will only a festival experience but a virtual find all the information and help you’ll festival experiment. need to watch films on your television, When Covid hit, Hamptons Doc Fest tablet or computer. So click on and went into overdrive. We were forced step into the big virtual world wherever to cancel our Docs Equinox Spring you are. -

CHANNEL GUIDE Corpus Christi, TX

CHANNEL GUIDE Corpus Christi, TX TV SERVICES BASIC TV 2 Univision HD 12 KZTV CBS HD 22 Azteca America 192 TBN HD CHANNELS 816 CW-HD 3 Local Weather 13 KDF Independent 23 HSN HD 193 Inspiration Network 802 Univision HD 817 Telemundo HD 4 QVC HD 14 Retro TV 96 C-SPAN 270 Charge! 804 QVC HD 823 HSN HD 5 KIII ABC HD 15 My Network TV 137 QVC Plus 280 Grit 805 KIII ABC HD 7 KRIS NBC HD 16 CW 138 HSN 2 281 MeTV 807 KRIS NBC HD 8 UniMás 17 Telemundo HD 139 Jewelry TV 282 ION 809 KEDT PBS HD MUSIC CHOICE 9 KEDT PBS HD 18 Public Access 173 PBS Create 283 Create 811 KUQI FOX HD 701-752 10 Public Access 19 Educational Access 190 Daystar 284 Cozi TV 812 KZTV CBS HD 11 KUQI FOX HD 20 City of Corpus Christi 191 EWTN 291 UniMás 292 LATV PREFERRED TV (includes Basic TV) 1 On Demand 46 MSNBC HD 69 Oxygen HD 246 IndiePlex 841 Weather Channel HD 865 Bravo HD 6 NewsNation HD 47 truTV HD 70 History Channel HD 247 RetroPlex 842 CNN HD 866 Galavision HD 24 TNT HD 48 OWN HD 71 Travel Channel HD 393 HBO** 843 HLN HD 867 Syfy HD 25 TBS HD 49 TV Land HD 72 HGTV HD 397 Amazon Prime** 844 Fox News HD 868 Comedy Central HD 26 USA HD 50 Discovery HD 73 Food Network HD 398 HULU** 845 CNBC HD 869 Oxygen HD 27 A&E HD 51 TLC HD 77 SEC Network HD 399 NETFLIX** 846 MSNBC HD 870 History Channel HD 28 Lifetime HD 52 Animal Planet HD 78 SEC Network - Alternative HD CHANNELS 847 truTV HD 871 Travel Channel HD 29 E! HD 53 Freeform HD 79 Fox Sports 2 HD 806 NewsNation HD 848 OWN HD 872 HGTV HD 54 Hallmark Channel HD 30 Paramount Network HD 82 Tennis Channel 824 TNT HD 849 TV Land -

Debunking Gasland, Part II

Debunking Gasland, Part II Steve Team Lead Three years after the release of Gasland – a film panned by independent observers as “fundamentally dishonest” and a “polemic” – the main challenge for director Josh Fox in releasing Gasland Part II was manifest: Regain the public’s trust by discarding hyperbole and laying out the challenges and opportunities of shale development as they actually exist in the actual world. In short, do everything a documentary filmmaker should do, but which he chose not to do in Gasland. Unfortunately for those who attended the premiere of Gasland Part II this past weekend (we were there), Josh eschewed that path entirely, doubling down on the same old, tired talking points, and playing to his narrow base at the exclusion of all others. The Parker County case? It’s in there. Dimock? Probably receives more focus than anything else. Pavillion and EPA? You bet. And yes, that damned banjo of his makes an appearance or two as well. This isn’t Gasland Part II, folks. It’s Gasland Too. Sure, the sequel has some new cast members and a few new claims. Somehow, Fox discovers that shale is actually worse than he previously thought: Earthquakes. Methane leaks. Well failures. Hurricanes. Heck, viewers were probably waiting for swarms of locusts to appear – fracking locusts, to be sure. And there was plenty of spectacle, too. Yoko Ono was in the audience. So was former Rep. Maurice Hinchey (D-N.Y.), the congressman who lent his name to the infamous “FRAC Act” that Josh so desperately wants to become law. -

Medical Television Programmes and Patient Behaviour

Gesnerus 76/2 (2019) 225–246, DOI: 10.24894/Gesn-en.2019.76011 Doing the Work of Medicine? Medical Television Programmes and Patient Behaviour Tim Boon, Jean-Baptiste Gouyon Abstract This article explores the contribution of television programmes to shaping the doctor-patient relationship in Britain in the Sixties and beyond. Our core proposition is that TV programmes on medicine ascribe a specifi c position as patients to viewers. This is what we call the ‘Inscribed Patient’. In this ar- ticle we discuss a number of BBC programmes centred on medicine, from the 1958 ‘On Call to a Nation’; to the 1985 ‘A Prize Discovery’, to examine how television accompanied the development of desired patient behaviour during the transition to what was dubbed “Modern Medicine” in early 1970s Brit- ain. To support our argument about the “Inscribed Patient”, we draw a com- parison with natural history programmes from the early 1960s, which simi- larly prescribed specifi c agencies to viewers as potential participants in wild- life fi lmmaking. We conclude that a ‘patient position’ is inscribed in biomedical television programmes, which advance propositions to laypeople about how to submit themselves to medical expertise. Inscribed patient; doctor-patient relationship; biomedical television pro- grammes; wildlife television; documentary television; BBC Horizon Introduction Television programmes on medical themes, it is true, are only varieties of tele- vision programming more broadly, sharing with those others their programme styles and ‘grammar’. But they -

Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance U.S

1 Check website or mobile app for full description and content information. description app for full Check website or mobile #sundance • sundance.org/festival sundance.org/festival Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance The U.S. Dramatic Competition Films As You Are The Birth of a Nation U.S. Dramatic Competition Dramatic U.S. Many of these films have not yet been rated by the Motion Picture Association of America. Read the full descriptions online and choose responsibly. Films are generally followed by a Q&A with the director and selected members of the cast and crew. All films are shown in 35mm, DCP, or HDCAM. Special thanks to Dolby Laboratories, Inc., for its support of our U.S.A., 2016, 110 min., color U.S.A., 2016, 117 min., color digital cinema projection. As You Are is a telling and retelling of a Set against the antebellum South, this story relationship between three teenagers as it follows Nat Turner, a literate slave and traces the course of their friendship through preacher whose financially strained owner, PROGRAMMERS a construction of disparate memories Samuel Turner, accepts an offer to use prompted by a police investigation. Nat’s preaching to subdue unruly slaves. Director, Associate Programmers Sundance Film Festival Lauren Cioffi, Adam Montgomery, After witnessing countless atrocities against 2 John Cooper Harry Vaughn fellow slaves, Nat devises a plan to lead his DIRECTOR: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte people to freedom. Director of Programming Shorts Programmers SCREENWRITERS: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, Trevor Groth Dilcia Barrera, Emily Doe, Madison Harrison Ernesto Foronda, Jon Korn, PRINCIPAL CAST: Owen Campbell, DIRECTOR/SCREENWRITER: Nate Parker Senior Programmers Katie Metcalfe, Lisa Ogdie, Charlie Heaton, Amandla Stenberg, PRINCIPAL CAST: Nate Parker, David Courier, Shari Frilot, Adam Piron, Mike Plante, Kim Yutani, John Scurti, Scott Cohen, Armie Hammer, Aja Naomi King, Caroline Libresco, John Nein, Landon Zakheim Mary Stuart Masterson Jackie Earle Haley, Gabrielle Union, Mike Plante, Charlie Reff, Kim Yutani Mark Boone Jr. -

Alphabetical Channel Guide 800-355-5668

Miami www.gethotwired.com ALPHABETICAL CHANNEL GUIDE 800-355-5668 Looking for your favorite channel? Our alphabetical channel reference guide makes it easy to find, and you’ll see the packages that include it! Availability of local channels varies by region. Please see your rate sheet for the packages available at your property. Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package 5StarMAX 712 774 Cinemax A&E 95 488 ABC 10 WPLG 10 410 Local Local Local Local ABC Family 62 432 AccuWeather 27 ActionMAX 713 775 Cinemax AMC 84 479 America TeVe WJAN 21 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package American Heroes Channel 112 Animal Planet 61 420 AWE 256 491 AXS TV 493 Azteca America 399 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package Bandamax 625 En Espanol Package Bang U 810 Adult BBC America 51 BBC World 115 Becon WBEC 397 Local Local Local Local beIN Sports 214 502 beIN Sports (en Espanol) 602 En Espanol Package BET 85 499 BET Gospel 114 Big Ten Network 208 458 Bloomberg 222 Boomerang 302 Bravo 77 471 Brazzers TV 811 Adult CanalSur 618 En Espanol Package Cartoon Network 301 433 CBS 4 WFOR 4 404 Local Local Local Local CBS Sports Network 201 459 Centric 106 Chiller 109 CineLatino 630 En Espanol Package Cinemax 710 772 Cinemax Cloo Network 108 CMT 93 CMT Pure Country 94 CNBC 48 473 CNBC World 116 CNN 49 465 CNN en Espanol 617 En Espanol Package CNN International 221 Comedy Central 29 426 Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package -

HBO and the HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, the HISTORICAL FILM, and PUBLIC HISTORY at WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the Facul

HBO AND THE HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, THE HISTORICAL FILM, AND PUBLIC HISTORY AT WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University December 2016 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________________ Raymond J. Haberski, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________ Thorsten Carstensen, Ph.D. __________________________________ Kevin Cramer, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank the members of my committee for supporting this project and offering indispensable feedback and criticism. I would especially like to thank my chair, Ray Haberski, for being one of the most encouraging advisers I have ever had the pleasure of working with and for sharing his passion for film and history with me. Thorsten Carstensen provided his fantastic editorial skills and for all the times we met for lunch during my last year at IUPUI. I would like to thank Kevin Cramer for awakening my interest in German history and for all of his support throughout my academic career. Furthermore, I would like to thank Jason M. Kelly, Claudia Grossmann, Anita Morgan, Rebecca K. Shrum, Stephanie Rowe, Modupe Labode, Nancy Robertson, and Philip V. Scarpino for all the ways in which they helped me during my graduate career at IUPUI. I also thank the IUPUI Public History Program for admitting a Germanist into the Program and seeing what would happen. I think the experiment paid off. -

![[ Captioner Standing by ] 1 >> the Broadcast Is Now Starting. All Attendees Are in Listen-Only Mode. >> JESSIE](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4385/captioner-standing-by-1-the-broadcast-is-now-starting-all-attendees-are-in-listen-only-mode-jessie-194385.webp)

[ Captioner Standing by ] 1 >> the Broadcast Is Now Starting. All Attendees Are in Listen-Only Mode. >> JESSIE

[ Captioner standing by ] 1 >> The broadcast is now starting. All attendees are in listen-only mode. >> JESSIE: Hello, everyone. Welcome to today's Webinar Understanding Chemsex Essentials for Testing the Addictive Fusion of Drug and Sex. It's so great that you could be with us here. I'm Jessica O'Brien. I will be the facilitator. Make sure to bookmark this page so you can stay up to date on all of the latest in addiction education. Closed captioning is provided by CaptionAccess. You will notice the Go-To Webinar. You can use the orange arrow at any point to minimize or maximize the menu and you can just move it out of the way if that's what is best for you. I will bring your attention to the questions box. We're going to gather any questions for our presenter today in the questions box and then ask him during the Q&A session at the -- towards the end of the presentation. So if you have any questions for Dr. Fawcett, feel free to right those in the Q&A box. Also, we have -- bringing your attention to the handouts tab. You can find a copy of the slides for today's presentation as well as a user-friendly instructional guide on how to access our online CE quiz and immediately earn your certificate. If you have never gotten a certificate from us before, make sure you use the instructions in our handout tab when you are ready to take the quiz. Every NAADAC Webinar has its own web page that houses everything that you need to know about that 2 particular Webinar. -

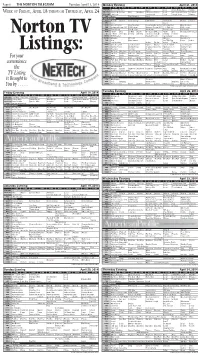

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam.