This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Israel Trip ITINERARY

ITINERARY The Cohen Camps’ Women’s Trip to Israel Led by Adina Cohen April 10-22, 2018 Tuesday April 10 DEPARTURE Departure from Boston (own arrangements) Wednesday April 11 BRUCHIM HABA’AIM-WELCOME TO ISRAEL! . Rendezvous at Ben Gurion airport at 14:10 (or at hotel in Tel Aviv) . Opening Program at the Port of Jaffa, where pilgrims and olim entered the Holy Land for centuries. Welcome Dinner at Café Yafo . Check-in at hotel Overnight: Carlton, Tel Aviv Thursday April 12 A LIGHT UNTO THE NATIONS . Torah Yoga Session . Visit Save a Child’s Heart-a project of Wolfston Hospital, in which Israeli pediatric surgeons provide pro-bono cardiac surery for children from all over Africa and the Middle East. “Shuk Bites” lunch in the Old Jaffa Flea Market . Visit “The Women’s Courtyard” – a designer outlet empowering Arab and Jewish local women . Israeli Folk Dancing interactive program- Follow the beat of Israeli women throughout history and culture and experience Israel’s transformation through dance. Enjoy dinner at the “Liliot” Restaurant, which employs youth at risk. Overnight: Carlton, Tel Aviv Friday April 13 COSMOPOLITAN TEL AVIV . Interactive movement & drum circle workshop with Batya . “Shuk & Cook” program with lunch at the Carmel Market . Stroll through the Nahalat Binyamin weekly arts & crafts fair . Time at leisure to prepare for Shabbat . Candle lighting Cohen Camps Women’s Trip to Israel 2018 Revised 22 Aug 17 Page 1 of 4 . Join Israelis for a unique, musical “Kabbalat Shabbat” with Bet Tefilah Hayisraeli, a liberal, independent, and egalitarian community in Tel Aviv, which is committed to Jewish spirit, culture, and social action. -

Hip Hop from '48 Palestine

Social Text Hip Hop from ’48 Palestine Youth, Music, and the Present/Absent Sunaina Maira and Magid Shihade This essay sheds light on the ways in which a particular group of Palestin- ian youth offers a critical perspective on national identity in the colonial present, using hip hop to stretch the boundaries of nation and articulate the notion of a present absence that refuses to disappear. The production of identity on the terrain of culture is always fraught in relation to issues of authenticity, displacement, indigeneity, and nationalism and no more so than in the ongoing history of settler colonialism in Palestine. In the last decade, underground hip hop produced by Palestinian youth has grown and become a significant element of a transnational Palestinian youth culture as well as an expression of political critique that has begun to infuse the global Palestinian rights movement. This music is linked to a larger phenomenon of cultural production by a Palestinian generation that has come of age listening to the sounds of rap, in Palestine as well as in the diaspora, and that has used hip hop to engage with the question of Palestinian self- determination and with the politics of Zionism, colonial- ism, and resistance. Our research focuses on hip hop produced by Palestinian youth within the 1948 borders of Israel, a site that reveals some of the most acute contradictions of nationalism, citizenship, and settler colonialism. Through hip hop, a new generation of “1948 Palestinians” is construct- ing national identities and historical narratives in the face of their ongoing erasure and repression.1 We argue that this Palestinian rap reimagines the geography of the nation, linking the experiences of “ ’48 Palestinians” to those in the Occupied Territories and in the diaspora, and producing an archive of censored histories. -

Jews and the West Legalization of Marijuana in Israel?

SEPTEMBER 2014 4-8 AMBASSADOR LARS FAABORG- ANDERSEN: A VIEW ON THE ISRAELI – PALESTINIAN CONFLICT 10-13 H.Е. José João Manuel THE FIRST AMBASSADOR OF ANGOLA TO ISRAEL 18-23 JEWS AND THE WEST AN OPINION OF A POLITOLOGIST 32-34 LEGALIZATION OF MARIJUANA IN ISRAEL? 10 Carlibah St., Tel-Aviv P.O. Box 20344, Tel Aviv 61200, Israel 708 Third Avenue, 4th Floor New York, NY 10017, U.S.A. Club Diplomatique de Geneva P.O. Box 228, Geneva, Switzerland Publisher The Diplomatic Club Ltd. Editor-in-Chief Julia Verdel Editor Eveline Erfolg Dear friends, All things change, and the only constant in spectrum of Arab and Muslim opinions, Writers Anthony J. Dennis the Middle East is a sudden and dramatic just as there is a spectrum of Jewish Patricia e Hemricourt, Israel change. opinions. Ira Moskowitz, Israel The Middle East is a very eventful region, As one of the most talented diplomats in Bernard Marks, Israel where history is written every day. Here history of diplomacy, Henry Kissinger Christopher Barder, UK you can witness this by yourself. It could said: “It is not a matter of what is true that Ilan Berman, USA be during, before or after a war – between counts, but a matter of what is perceived wars. South – North, North – South, to be true.” war – truce, truce – war, enemy – friend, Reporters Ksenia Svetlov Diplomacy, as opposed to war, facilitates Eveline Erfolg friend – enemy… Sometimes, these words (or sometimes hinders) conflict prevention David Rhodes become very similar here. and resolution, before armed conflict Neill Sandler “A la guerre comme à la guerre” and begins. -

Tel Aviv Elite Guide to Tel Aviv

DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES TEL AVIV ELITE GUIDE TO TEL AVIV HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV 3 ONLY ELITE 4 Elite Traveler has selected an exclusive VIP experience EXPERT RECOMMENDATIONS 5 We asked top local experts to share their personal recommendations ENJOY ELEGANT SEA-FACING LUXURY AT THE CARLTON for the perfect day in Tel Aviv WHERE TO ➤ STAY 7 ➤ DINE 13 ➤ BE PAMPERED 16 RELAX IN STYLE AT THE BEACH WHAT TO DO ➤ DURING THE DAY 17 ➤ DURING THE NIGHT 19 ➤ FEATURED EVENTS 21 ➤ SHOPPING 22 TASTE SUMPTUOUS GOURMET FLAVORS AT YOEZER WINE BAR NEED TO KNOW ➤ MARINAS 25 ➤ PRIVATE JET TERMINALS 26 ➤ EXCLUSIVE TRANSPORT 27 ➤ USEFUL INFORMATION 28 DISCOVER CUTTING EDGE DESIGNER STYLE AT RONEN ChEN (C) ShAI NEIBURG DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES ELITE DESTINATION GUIDE | TEL AVIV www.elitetraveler.com 2 HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV Don’t miss out on the wealth of attractions, adventures and experiences on offer in ‘The Miami of the Middle East’ el Aviv is arguably the most unique ‘Habuah’ (‘The Bubble’), for its carefree Central Tel Aviv’s striking early 20th T city in Israel and one that fascinates, and fun-loving atmosphere, in which century Bauhaus architecture, dubbed bewilders and mesmerizes visitors. the difficult politics of the region rarely ‘the White City’, is not instantly Built a mere century ago on inhospitable intrudes and art, fashion, nightlife and attractive, but has made the city a World sand dunes, the city has risen to become beach fun prevail. This relaxed, open vibe Heritage Site, and its golden beaches, a thriving economic hub, and a center has seen Tel Aviv named ‘the gay capital lapped by the clear azure Mediterranean, of scientific, technological and artistic of the Middle East’ by Out Magazine, are beautiful places for beautiful people. -

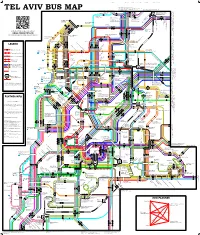

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005 BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights i BADIL is a member of the Global Palestine Right of Return Coalition Preface The Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons is published annually by BADIL Resource Center. The Survey provides an overview of one of the largest and longest-standing unresolved refugee and displaced populations in the world today. It is estimated that two out of every five of today’s refugees are Palestinian. The Survey has several objectives: (1) It aims to provide basic information about Palestinian displacement – i.e., the circumstances of displacement, the size and characteristics of the refugee and displaced population, as well as the living conditions of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons; (2) It aims to clarify the framework governing protection and assistance for this displaced population; and (3) It sets out the basic principles for crafting durable solutions for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, consistent with international law, relevant United Nations Resolutions and best practice. In short, the Survey endeavors to address the lack of information or misinformation about Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, and to counter political arguments that suggest that the issue of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons can be resolved outside the realm of international law and practice applicable to all other refugee and displaced populations. The Survey examines the status of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons on a thematic basis. Chapter One provides a short historical background to the root causes of Palestinian mass displacement. -

Million Book Collection

E TURKS IN PALESTINE BY ALEXANDER AARONSOHf WITH THE TURKS IN PALESTINE Photograph, Undern-innl \- /"/<>/<nr<>nd, -A*.r. DJEMAL PASHA WITH THE TURKS IN PALESTINE BY ALEXANDER AARONSOHN With Illustrations BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY fiibcrjibe pce 1916 COPYRIGHT, lQl6, BY THE ATLANTIC MONTHLY COMPANY COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY HOUGHTONMIFFLIN COMPANY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published October iqib TO MY MOTHER WHO LIVED AND FOUGHT AND DIED FOB A REGENERATED PALESTINE What have I done, or tried, or said In thanks to that dear woman dead ? MASEFIELD ACKNOWLEDGMENT To the editors of the Ailantic Monthly, to the publishers, and to the many friends who have encouraged me, I am and shall ever remain grateful CONTENTS INTRODUCTION xiii I. ZlCRON-jACOB 1 II. PRESSED INTO THE SERVICE 7 III. THE GERMAN PROPAGANDA 18 IV. ROAD-MAKING AND DISCHARGE 23 V. THE HIDDEN ARMS 29 VI. THE SUEZ CAMPAIGN 36 VII. FIGHTING THE LOCUSTS 49 VIII. THE LEBANON 53 IX. A ROBBER BARON OF PALESTINE 62 X. A RASH ADVENTURE 70 XI. ESCAPE 78 ILLUSTRATIONS DJEMALPASHA Frontispiece Photographby Underwood& Underwood THE CEMETERYOF ZICHON-JACOB 2 SAFFED 10 Photographby Underwood& Underwood THE AUTHOR ON HIS HORSE KOCHBA 14 Photographby Mr. Julius Rosemcald,of Chicago,in Marsh,19 H SOLDIERS'TENTS m SAMARIA 18 NAZARETH, FROM THE NORTHEAST 26 Photographby Underwood& Underwood HOUSE OF THE AUTHOR'S FATHER, EPHKAIM FISHL AARON- SOHN,IN ZlCRON-jACOB 30 IN A NATIVE CAFE, SAFFED 36 Photographby Mr. Julius Rosenwtdd A LEMONADE-SELLER OF DAMASCUS 36 Photographby Mr. Julius Rosenwald RAILROAD STATION SCENE BETWEEN HAIFA AND DAMASCUS 46 Photograph by Mr. -

SALT in the WATER: RACIALIZATION, HIERARCHY and ARAB-JEWISH ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS in ISRAEL by JANINE ANDREA CUROTTO RICH Submi

SALT IN THE WATER: RACIALIZATION, HIERARCHY AND ARAB-JEWISH ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS IN ISRAEL by JANINE ANDREA CUROTTO RICH Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University June 2019 JANINE ANDREA CUROTTO RICH 2019 © All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT SALT IN THE WATER: RACIALIZATION, HIERARCHY AND ARAB-JEWISH ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS IN ISRAEL JANINE ANDREA CUROTTO RICH CULTURAL STUDIES M.A. THESIS, JUNE 2019 Thesis Supervisor: Asst. Prof. AYŞECAN TERZİOĞLU Key words: Israel, Racialization, Jewish Identity, Colonialism, Hierarchy This paper examines the specter of romantic relationships between Arabs and Jews in Israel. Given the statistical rarity of such relationships, the extensive public, media, and governmental attention paid to preventing ‘miscegenation’ seems paradoxical. I begin with an exploration of these attempts, which range from highly successful advertising campaigns and televised interventions to citizen patrol groups, physical assault, and, in the case of underage women, incarceration in reform schools. By turning to work on racializing processes within contested colonial space, this research traces the specter of ‘mixed’ relationships back to fears of internal contamination and the unstable nature of racial membership within racialized hierarchies of power. I conclude with a close analysis of three works – two novels and one film – that revolve around relationships between Arab and Jewish characters. By examining the way these texts both reify and challenge assemblages of race and belonging in Israel, I argue that these works should be viewed as theoretical texts that strive to present possibilities for a different future. iv ÖZET SUDAKİ TUZ: İSRAİL’DE IRKSALLAŞMA, HİYERARŞİ VE ARAP-YAHUDİ ROMANTİK İLİŞKİLERİ JANINE ANDREA CUROTTO RICH KÜLTÜREL ÇALISMALAR YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ, HAZIRAN 2019 Tez Danışmanı: Dr. -

Asilo Politico in Israele

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lavoro, cittadinanza sociale, interculturalità Tesi di Laurea Asilo politico in Israele Relatore Ch. ma Prof. ssa Emanuela Trevisan Correlatore Ch. Prof. Lauso Zagato Laureanda Caterina Santin Matricola 824639 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 1 2 Indice generale Introduzione.........................................................................................................................................5 CAPITOLO I: Il diritto d’asilo in Israele dal 1948 al 2006.......................................................................8 1.1 Nascita dello Stato di Israele: ideologia sionista, teorie etnocentriche e concetto di Otherness.........................................................................................................................................8 1.1.1 La storia..............................................................................................................................8 1.1.2 Il movimento sionista.......................................................................................................10 1.1.3 Gli inizi dell'immigrazione ebraica...................................................................................11 1.1.4 Le teorie etnocentriche....................................................................................................13 1.1.5 We-ness e Otherness........................................................................................................16 1.2 Il sistema migratorio................................................................................................................19 -

Signatories. Appeal from Palestine. 20.6

19/06/2020 Signatories for “Appeal from Palestine to the Peoples and States of the World” Name Current/ Previous Occupation 1. Abbas Zaki Member of the Central Committee of Fatah—Ramallah 2. Abd El-Qader Husseini Chairman of Faisal Husseini Foundation— Jerusalem 3. Abdallah Abu Alhnoud Member of the Fatah Advisory Council— Gaza 4. Abdallah Abu Hamad President of Taraji Wadi Al-Nes Sports Club—Bethlehem 5. Abdallah Hijazi President of the Civil Retired Assembly, Former Ambassador—Ramallah 6. Abdallah Yousif Alsha’rawi President of the Palestinian Motors Sport & Motorcycle & Bicycles Federation— Ramallah 7. Abdel Halim Attiya President of Al-Thahirya Youth Club— Hebron 8. Abdel Jalil Zreiqat President of Tafouh Youth Sports Club— Hebron 9. Abdel Karim Abu Khashan University Lecturer, Birzeit University— Ramallah 10. Abdel Majid Hijeh Secretary-General of the Olympic Committee—Ramallah 11. Abdel Majid Sweilem University Lecturer and Journalist— Ramallah 12. Abdel Qader Hasan Abdallah Secretary General of the Palestine Workers Kabouli Union—Lebanon, Alkharoub Region 13. Abdel Rahim Mahamid Secretary of the Al-Taybeh Sports Club— Ramallah 14. Abdel Raof Asqoul Storyteller—Tyre 15. Abdel Salam Abu Nada Expert in Media Development—Brussels 16. Abdel-Rahman Tamimi Director General of the Palestinian Hydrology Group—Ramallah 17. Abdo Edrisi President of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry—Hebron 18. Abdul Rahman Bseiso Retired Ambassador—Cyprus 19. Abdul Rahman Hamad Former Minister—Gaza 20. Abu Ali Masoud Vice-Chairman of the Fatah Advisory Council—Ramallah 21. Adalah Abu Sitta Chairwoman of the Board of Directors of the Right to Live Society—Gaza 22. Adel Al-Asta Writer—Gaza 23. -

1948 Arab‒Israeli

1948 Arab–Israeli War 1 1948 Arab–Israeli War מלחמת or מלחמת העצמאות :The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, known to Israelis as the War of Independence (Hebrew ,מלחמת השחרור :, Milkhemet Ha'atzma'ut or Milkhemet HA'sikhror) or War of Liberation (Hebrewהשחרור Milkhemet Hashikhrur) – was the first in a series of wars fought between the State of Israel and its Arab neighbours in the continuing Arab-Israeli conflict. The war commenced upon the termination of the British Mandate of Palestine and the Israeli declaration of independence on 15 May 1948, following a period of civil war in 1947–1948. The fighting took place mostly on the former territory of the British Mandate and for a short time also in the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon.[1] ., al-Nakba) occurred amidst this warﺍﻟﻨﻜﺒﺔ :Much of what Arabs refer to as The Catastrophe (Arabic The war concluded with the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Background Following World War II, on May 14, 1948, the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end. The surrounding Arab nations were also emerging from colonial rule. Transjordan, under the Hashemite ruler Abdullah I, gained independence from Britain in 1946 and was called Jordan, but it remained under heavy British influence. Egypt, while nominally independent, signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 that included provisions by which Britain would maintain a garrison of troops on the Suez Canal. From 1945 on, Egypt attempted to renegotiate the terms of this treaty, which was viewed as a humiliating vestige of colonialism. Lebanon became an independent state in 1943, but French troops would not withdraw until 1946, the same year that Syria won its independence from France. -

Elections 2013 ENG Issue 2

Issue 2, January 21, 2013 November 2012 Table of Contents From the Editor’s Desk ............................................................................2 Editorial .....................................................................................................4 Elie Rekhess / The End to Parliamentary Politics in Arab Society?..........................4 Mohanad Mustafa / The Islamic Movement and Abstention from Voting in the Knesset Elections .......................................................................................................7 Main Issues in the 2013 Elections Campaigns .....................................10 The Main Question is to Vote or not to Vote...........................................................10 In Favor of Voting ...................................................................................................11 Against Participation in the Elections......................................................................12 Reactions to the attempts to disqualify MK Hanin Zoabi........................................13 Party Preparations for Election Day.....................................................14 Hadash......................................................................................................................14 Balad ........................................................................................................................15 Ra’am-Ta’al-Mada...................................................................................................16 Da’am – The Democratic