Iron, Steel and Swords Script - Page 1 the Basic Technique Is Exactly the Same in Both Cases: Take a Rock and Chisel Off What You Don't Want

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Iron-Making Process

Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site www.nps.gov/hofu Teacher’s Guide The Iron-Making Process The Ingredients The four main ingredients for making iron were present in the area of Hopewell and were a reason for the furnace’s location. I. Wood A. Used as a primary energy source in village operations 1. As charcoal to power the furnace and blacksmith shop 2. As fuel for heating and cooking B. Used as building material for: 1. Homes 2. Wagons and equipment II. Water A. Used to turn the water wheel connected to the bellows which forced blasts of air into the furnace to increase the heat B. Used for: 1. Drinking 2. Bathing 3. Cooking 4. Washing 5. Cleaning III. Iron Ore Iron ore was dug from open-pit mines near Hopewell, then hauled to Hopewell Furnace in carts and wagons IV. Limestone Used as a “flux,” which removed impurities from the ore as the iron ore was smelted; it was quarried near Morgantown and from Hopewell Plantation lands The Process This process was also called smelting. I. In the furnace, the charcoal burns with a great amount of heat. II. The water wheel was attached to a huge bellows and later to blowing tubs — like can be seen at Hopewell today — which blasted the charcoal with air to increase the heat. III. The furnace was filled, or “charged,” from the top in this order: A. Fire B. Charcoal Iron-Making Process Page 1 C. Iron Ore D. Limestone E. Charcoal F. Iron Ore G. The process continued and repeated as the ore melted IV. -

Schoolcraft Blast Furnace

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore Schoolcraft National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Blast Furnace Schoolcraft furnace With surveyor William Burt’s discovery of iron ore near Teal Lake in Marquette County in 1844, Michigan’s Upper Peninsula suddenly became a hub of activity. The discovery led to construction of a vast mining and manufacturing industry using forges and blast furnaces. When the Civil War ended, many of the South’s furnaces had been destroyed by the war. Westward expansion was occurring across the plains and demand for iron boomed. It was during this era that many of the Upper Peninsula’s furnaces were constructed. There were advantages to smelting iron ore from charcoal fires. Iron produced in this manner was low in carbon content, making it highly fusable, strong, malleable and able to withstand shocks without cracking. The iron made fine wagon rims, horseshoes, and railroad wheels. Before the boom times were over, 29 separate furnaces were located on the Old Munising, ca. 1870 peninsula, though not all operated simultaneously. The business of iron making required more capital than was readily available in the area and financing and management of the operations was often complex. The first group of investors were from Philadelphia. They wished to develop a resort village on Munising Bay’s east shoreline in 1850. Some 87,000 acres of timber were purchased for $.85 an acre. A village was platted on the east shore of Munising Bay, lots were sold, and a dock was built. Henry Mather and Peter White acted as agents for the group of investors who created the Schoolcraft Iron Company in 1866. -

Effects of Carburization Time and Temperature on the Mechanical Properties of Carburized Mild Steel, Using Activated Carbon As Carburizer

Materials Research, Vol. 12, No. 4, 483-487, 2009 © 2009 Effects of Carburization Time and Temperature on the Mechanical Properties of Carburized Mild Steel, Using Activated Carbon as Carburizer Fatai Olufemi Aramidea,*, Simeon Ademola Ibitoyeb, Isiaka Oluwole Oladelea, Joseph Olatunde Borodea aMetallurgical and Materials Engineering Department, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria bMaterials Science and Engineering Department, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria Received: July 31, 2009; Revised: September 25, 2009 Due to the complexity of controlling parameters in carburization, there has been relatively little work on process variables during the surface hardening process. This work focuses on the effects of the carburizing temperature and time on the mechanical properties of mild steel carburized with activated carbon, at 850, 900 and 950 °C, soaked at the carburizing temperature for 15 and 30 minutes, quenched in oil, tempered at 550 °C and held for 60 minutes. Prior carburization process, standard test samples were prepared from the as received specimen for tensile and impact tests. After carburization process, the test samples were subjected to the standard test and from the data obtained, ultimate tensile strength, engineering strain, impact strength, Youngs’ moduli were calculated. The case and core hardness of the carburized tempered samples were measured. It was observed that the mechanical properties of mild steels were found to be strongly influenced by the process of carburization, carburizing temperature and soaking time at carburizing temperature. It was concluded that the optimum combination of mechanical properties is achieved at the carburizing temperature of 900 °C followed by oil quenching and tempering at 550 °C. -

Higher-Quality Electric-Arc Furnace Steel

ACADEMIC PULSE Higher-Quality Electric-Arc Furnace Steel teelmakers have traditionally viewed Research Continues to Improve the electric arc furnaces (EAFs) as unsuitable Quality of Steel for producing steel with the highest- Even with continued improvements to the Squality surface finish because the process design of steelmaking processes, the steelmaking uses recycled steel instead of fresh iron. With over research community has focused their attention 100 years of processing improvements, however, on the fundamental materials used in steelmaking EAFs have become an efficient and reliable in order to improve the quality of steel. In my lab steelmaking alternative to integrated steelmaking. In at Carnegie Mellon University, we have several fact, steel produced in a modern-day EAF is often research projects that deal with controlling the DR. P. BILLCHRIS MAYER PISTORIUS indistinguishable from what is produced with the impurity concentration and chemical quality of POSCOManaging Professor Editorof Materials integrated blast-furnace/oxygen-steelmaking route. steel produced in EAFs. Science412-306-4350 and Engineering [email protected] Mellon University Improvements in design, coupled with research For example, we recently used mathematical developments in metallurgy, mean high-quality steel modeling to explore ways to control produced quickly and energy-efficiently. phosphorus. Careful regulation of temperature, slag and stirring are needed to produce low- Not Your (Great-) Grandparent’s EAF phosphorus steel. We analyzed data from Especially since the mid-1990s, there have been operating furnaces and found that, in many significant improvements in the design of EAFs, cases, the phosphorus removal reaction could which allow for better-functioning burners and a proceed further. -

5. Sirhowy Ironworks

Great Archaeological Sites in Blaenau Gwent 5. SIRHOWY IRONWORKS There were a number of ironworks in the area now covered by Blaenau Gwent County Borough, which provided all the raw materials they needed – iron ore, limestone and fuel, charcoal at first but later coal to make coke. The Sirhowy ironworks (SO14301010) are the only one where there is still something to see. The works were opened in 1778 with one blast furnace. Although it was originally blown by water power, in 1799 the owners invested in a Boulton and Watt steam engine. This gave them enough power to blow a second furnace, which started production in 1802. In the early years of the 19th century, the pig iron produced at Sirhowy was sent to the Tredegar works a little further down the valley where it was refined, until 1818 when the Sirhowy works were sold and started to send its pig iron to Ebbw Vale. A third furnace was added in 1826 and a fourth in 1839. But by the 1870s iron smelting at Sirhowy was no longer profitable, and the works finally closed in 1882. Like all ironworks in South Wales, the furnaces were built against a steep bank which enabled the ironworkers to load the charge of iron ore, limestone and coke or charcoal fuel more easily at the top of the furnace. All that is now left now are the remains of a bank of blast furnaces with the arches that would originally have linked them to the casting houses in front, and the building that originally housed the waterwheel. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property

NFS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multipler Propertyr ' Documentation Form NATIONAL This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ____Iron and Steel Resources of Pennsylvania, 1716-1945_______________ B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________ ~ ___Pennsylvania Iron and Steel Industry. 1716-1945_________________ C. Geographical Data Commonwealth of Pennsylvania continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, J hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requiremerytS\set forth iri36JCFR PafrfsBOfcyid the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official Date / Brent D. Glass Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple -

Three Hundred Years of Assaying American Iron and Iron Ores

Bull. Hist. Chem, 17/18 (1995) 41 THREE HUNDRED YEARS OF ASSAYING AMERICAN IRON AND IRON ORES Kvn K. Oln, WthArt It can reasonably be argued that of all of the industries factors were behind this development; increased pro- that made the modern world possible, iron and steel cess sophistication, a better understanding of how im- making holds a pivotal place. Without ferrous metals purities affected iron quality, increased capital costs, and technology, much of the modem world simply would a generation of chemically trained metallurgists enter- not exist. As the American iron industry grew from the ing the industry. This paper describes the major advances isolated iron plantations of the colonial era to the com- in analytical development. It also describes how the plex steel mills of today, the science of assaying played 19th century iron industry serves as a model for the way a critical role. The assayer gave the iron maker valu- an expanding industry comes to rely on analytical data able guidance in the quest for ever improving quality for process control. and by 1900 had laid down a theoretical foundation for the triumphs of steel in our own century. 1500's to 1800 Yet little is known about the assayer and how his By the mid 1500's the operating principles of assay labo- abilities were used by industry. Much has been written ratories were understood and set forth in the metallurgi- about the ironmaster and the furnace workers. Docents cal literature. Agricola's Mtll (1556), in period dress host historic ironmaking sites and inter- Biringuccio's rthn (1540), and the pret the lives of housewives, miners, molders, clerks, rbrbühln (Assaying Booklet, anon. -

Henry Bessemer and the Mass Production of Steel

Henry Bessemer and the Mass Production of Steel Englishmen, Sir Henry Bessemer (1813-1898) invented the first process for mass-producing steel inexpensively, essential to the development of skyscrapers. Modern steel is made using technology based on Bessemer's process. Bessemer was knighted in 1879 for his contribution to science. The "Bessemer Process" for mass-producing steel, was named after Bessemer. Bessemer's famous one-step process for producing cheap, high-quality steel made it possible for engineers to envision transcontinental railroads, sky-scraping office towers, bay- spanning bridges, unsinkable ships, and mass-produced horseless carriages. The key principle is removal of impurities from the iron by oxidation with air being blown through the molten iron. The oxidation also raises the temperature of the iron mass and keeps it molten. In the U.S., where natural resources and risk-taking investors were abundant, giant Bessemer steel mills sprung up to drive the expanding nation's rise as a dominant world economic and industrial leader. Why Steel? Steel is the most widely used of all metals, with uses ranging from concrete reinforcement in highways and in high-rise buildings to automobiles, aircraft, and vehicles in space. Steel is more ductile (able to deform without breakage) and durable than cast iron and is generally forged, rolled, or drawn into various shapes. The Bessemer process revolutionized steel manufacture by decreasing its cost. The process also decreased the labor requirements for steel-making. Prior to its introduction, steel was far too expensive to make bridges or the framework for buildings and thus wrought iron had been used throughout the Industrial Revolution. -

Studying and Improving Blast Furnace Cast Iron Quality

Т. К. BALGABEKOV, D. K. ISSIN, B. M. KIMANOV, A. Z. ISSAGULOV, ISSN 0543-5846 ZH. D. ZHOLDUBAYEVA, А. Z. AKASHEV, B. D. ISSIN METABK 53(4) 556-558 (2014) UDC – UDK 669.162.2:669.1:669.13=111 STUDYING AND IMPROVING BLAST FURNACE CAST IRON QUALITY Received – Prispjelo: 2013-11-09 Accepted – Prihvaćeno: 2014-04-30 Preliminary Note – Prethodno priopćenje In the article there are presented the results of studies to improve the quality of blast furnace cast iron. It was estab- lished that using fire clay suspension for increasing the mould covering heat conductivity improves significantly pig iron salable condition and filtration refining method decreases iron contamination by nonmetallic inclusions by 50 – 70 %. Key words: blast furnace, cast iron, fire clay, filter, filtering elements INTRODUCTION tically contain water after mould drying with coke gas. Therefore, pig iron salable condition improves signifi- With the development of motor transport industry, cantly. machine-tool building and other machine building Besides, the use of fire clay for mould coverings ex- branches there increased the requirements to the quality cludes claps in dissolution and prevents the lime solu- of blast furnace cast iron. With the use in the cupola tion corroding action when split on the open parts of the mixture of cast iron melted in large-volume furnaces worker’s body, increases the culture of production and with the melting progressive parameters, at machine decreases labor intensity when making solution, as there building plants there became often defective castings is excluded the waste presence up to 30 – 40 % in the with shrinkage defects, friability, cracks. -

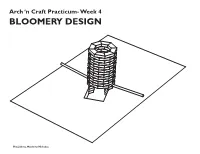

Bloomery Design

Arch ‘n Craft Practicum- Week 4 BLOOMERY DESIGN Hiu, Julieta, Matthew, Nicholas 7 3/4" The Stack: 3 3/4" In our ideal model we would use refractory bricks, either rectangular bricks or curved bricks which would help us make a circular 1'-8" stack. The stack would be around 3 feet tall with a 1 foot diameter for the inner wall of the stack. There will be openings about 3 brick lengths up(6-9 inches) from the ground on 1'-0" opposite ends of the stack. Attached to these openings will be our tuyeres which in turn will connect to our air sources. Building a circular stack would be beneficial to the type of air distribution we want to create within our furnace; using two angled tuyeres we would like air to move clockwise and counterclock- Bloomery Plan wise. We would like to line the inside of the stack with clay to provide further insulation. Refractory bricks would be an ideal material to use because the minerals they are com- posed of do not change chemically when 1'-0" exposed to high heat, some examples of these materials are aluminum, manganese, silica and zirconium. Other comments: 3'-0" Although we have opted to use refractory bricks, which would be practical for our intended purpose, we briefly considered using Vycor glass which can withstand high tem- peratures of up to 900 degrees celsius or approximately 1652 degrees Fahrenheit, which Tuyere height: Pitched -10from horizontal 7" would be enough for our purposes. Bloomery Section Ore/ Charcoal: Our group has decided to use Magnetite ore along with charcoal for the smelt. -

History of the Hardening of Steel : Science and Technology J

HISTORY OF THE HARDENING OF STEEL : SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY J. Vanpaemel To cite this version: J. Vanpaemel. HISTORY OF THE HARDENING OF STEEL : SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY. Journal de Physique Colloques, 1982, 43 (C4), pp.C4-847-C4-854. 10.1051/jphyscol:19824139. jpa- 00222126 HAL Id: jpa-00222126 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/jpa-00222126 Submitted on 1 Jan 1982 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. JOURNAL DE PHYSIQUE Colloque C4, suppZ4ment au no 12, Tome 43, de'cembre 1982 page C4-847 HISTORY OF THE HARDENING OF STEEL : SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 3. Vanpaemel Center for historical and socio-economical studies on science and technology Teer EZstZaan 41, 3030 Leuven, SeZgim (Accepted 3 November 1982) Abstract. - The knowledge of the hardening phenomenon was achieved through a very cumulative process without any dis- continuity or 'scientific crisis' . The history of the hardening shows a definite interrelationship between techno- logical approach (or the application-side) and academic science . The hardening of steel appears to have been an operation in common use among the early Greeks The Greek and Roman smiths knew, from experience, how to control the. -

Guide to Non-Ferrous Metals

14 Manufacturing Processes CHAPTER 2 Ferrous Materials and Non-Ferrous Metals and Alloys 2.1 INTRODUCTION Ferrous materials/metals may be defined as those metals whose main constituent is iron such as pig iron, wrought iron, cast iron, steel and their alloys. The principal raw materials for ferrous metals is pig iron. Ferrous materials are usually stronger and harder and are used in daily life products. Ferrous material possess a special property that their characteristics can be altered by heat treatment processes or by addition of small quantity of alloying elements. Ferrous metals possess different physical properties according to their carbon content. 2.2 IRON AND STEEL The ferrous metals are iron base metals which include all varieties of iron and steel. Most common engineering materials are ferrous materials which are alloys of iron. Ferrous means iron. Iron is the name given to pure ferrite Fe, as well as to fused mixtures of this ferrite with large amount of carbon (may be 1.8%), these mixtures are known as pig iron and cast iron. Primarily pig iron is produced from the iron ore in the blast furnace from which cast iron, wrought iron and steel can be produced. 2.3 CLASSIFICATION OF CARBON STEELS Plain carbon steel is that steel in which alloying element is carbon. Practically besides iron and carbon four other alloying elements are always present but their content is very small that they do not affect physical properties. These are sulphur, phosphorus, silicon and manganese. Although the effect of sulphur and phosphorus on properties of steel is detrimental, but their percentage is very small.