CBD Fifth National Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heart of Borneo a Natural Priority for a Green Economy

HoB 2012 Heart of Borneo A natural priority for a green economy Map 100% RECYCLED TOWARDS A GREEN ECONOMY IN THE HEART OF BORNEO HOW WWF SUPPORTS THE THREE GOVERNMENTS IN THE HEART OF BORNEO INITIATIVE Business and Economics Sustainable Landscape Management Enabling Conditions Species Conservation Sustainable forestry Protected areas Ecosystem-based spatial planning Safeguarding Flagship species In 2011, WWF Indonesia’s Global Forest & Trade Network signed a There are almost 4 million ha of protected areas within the HoB, these WWF is working with governments to integrate the value of Elephant and rhino work in key habitats in Sabah in 2010 continued FACTSHEETS Participation Agreement with the biggest single forest concession holder in the provide a vital refuge for critically endangered species. The HoB is ecosystem and biodiversity into government’s land-use plans and with the establishment of a rhino protection unit, evaluation of HoB. The agreement covers more than 350,000 hectares and is considered a currently one of only two places on Earth where orangutans, elephants, policies. In Indonesia this includes the development of a spatial plan enforcement policies and legislation, and the creation of an elephant milestone for WWF, representing a significant commitment towards sustainable 1 Seeking a Bird’s Eye View on Orang-utan Survival rhinos and clouded leopards coexist and is likely to be the only future specific to the Heart of Borneo based on the value of providing action plan. forest management. stronghold for these species. Protected areas are the backbone of WWF’s water-related ecosystem services, carbon sequestration and as a 2 Forest Restoration Programme in North Ulu Segama, Sabah work to protect these iconic endangered species and the organization will global biodiversity hotspot. -

Cop15 Inf. 9 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement En Anglais)

CoP15 Inf. 9 (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Doha (Qatar), 13-25 March 2010 TIGER RANGE STATE REPORT – MALAYSIA ∗ The attached document has been submitted by Malaysia in compliance with Decision 14.65 (Asian big cats). ∗ The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. CoP15 Inf. 9 – p. 1 CoP15 Inf. 9 Annex Report prepared by: Department of Wildlife and National Parks (DWNP), Peninsular Malaysia. In compliance to Decision 14.65 on Asian Big Cats MANAGEMENT AND CONSERVATION OF TIGER IN MALAYSIA. 1. Legal status In Peninsular Malaysia, tiger (Panthera tigris) is listed as totally protected species under the Protection of Wild Life Act 1972. Under the Wild Life Protection Ordinance 1998 (State of Sarawak), tiger is listed under Protected animals category whereas Sabah Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1997 accorded totally protected status to tiger. For further clarification, tiger is not found in Sabah and Sarawak. In Peninsular Malaysia, trade in tiger is only allowed for non commercial purposes such as research, captive breeding programme and exchange between zoological parks. For these activities, permission in term of Special Permit from the Minister of Natural Resources and Environment of Malaysia is required. -

Detailed Species Accounts from The

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

THE ENVIRONMENTAL STATUS of the HEART of BORNEO V Introduction

REPORT HoB The Environmental Status 2014 of the Heart of Borneo Main author: Stephan Wulffraat GIS production: Khairil Fahmi Faisal; I Bagus Ketut Wedastra; Aurelie Shapiro Photos: as credited in captions. Published: January 2014 by WWF’s HoB Initiative Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. © Text 2014 WWF All rights reserved ISBN 978-602-19901-0-0 WWF is one of the world’s largest and most experienced independent con- servation organisations, with more than five million supporters and a global network active in more than 100 countries. WWF’s mission is to stop the degradation of the planet’s natural environ- ment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature, by: conserving the world’s biological diversity, ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable, and promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption. THE ENVIRONMENTAL STATUS OF THE HEART OF BORNEO V Introduction The island of Borneo, encompassing parts of HoB is also known for the cultural and linguistic Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei, is recognized diversity of the several ethnic groups of as a global conservation priority, yet over the indigenous peoples collectively known as Dayak. last few decades the lowland portions of the Local people depend on the forest for a variety island of Borneo in Indonesia has suffered of resources including: food, medicinal plants, from deforestation, forest fire, and conversion non-timber forest products for trade, wild game, to estate crops. The central upland portions of fish, construction materials and water. -

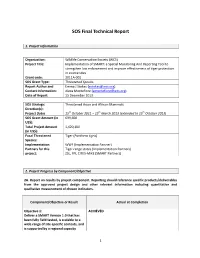

SOS Final Technical Report

SOS Final Technical Report 1. Project Information Organization: Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Project Title: Implementation of SMART: a Spatial Monitoring And Reporting Tool to strengthen law enforcement and improve effectiveness of tiger protection in source sites Grant code: 2011A-001 SOS Grant Type: Threatened Species Report Author and Emma J Stokes ([email protected]) Contact Information: Alexa Montefiore ([email protected]) Date of Report: 15 December 2013 SOS Strategic Threatened Asian and African Mammals Direction(s): Project Dates 15th October 2011 – 15th March 2013 (extended to 15th October 2013) SOS Grant Amount (in 699,600 US$): Total Project Amount 1,420,100 (in US$): Focal Threatened Tiger (Panthera tigris) Species: Implementation WWF (Implementation Partner) Partners for this Tiger range states (Implementation Partners) project: ZSL, FFI, CITES-MIKE (SMART Partners) 2. Project Progress by Component/Objective 2A. Report on results by project component. Reporting should reference specific products/deliverables from the approved project design and other relevant information including quantitative and qualitative measurement of chosen indicators. Component/Objective or Result Actual at Completion Objective 1: ACHIEVED Deliver a SMART Version 1.0 that has been fully field-tested, is scalable to a wide range of site-specific contexts, and is supported by a regional capacity 1 building strategy. Result 1.1: - SMART 1.0 publicly released Feb 2013. A SMART system that is scalable, fully - Two subsequent updates released based on early field-tested and supported by a regional field testing (current version 1.1.2) capacity building strategy is in place in 9 - Software translated into Thai, Vietnamese and implementation sites. -

Buku Daftar Senarai Nama Jurunikah Kawasan-Kawasan Jurunikah Daerah Johor Bahru Untuk Tempoh 3 Tahun (1 Januari 2016 – 31 Disember 2018)

BUKU DAFTAR SENARAI NAMA JURUNIKAH KAWASAN-KAWASAN JURUNIKAH DAERAH JOHOR BAHRU UNTUK TEMPOH 3 TAHUN (1 JANUARI 2016 – 31 DISEMBER 2018) NAMA JURUNIKAH BI NO KAD PENGENALAN MUKIM KAWASAN L NO TELEFON 1 UST. HAJI MUSA BIN MUDA (710601-01-5539) 019-7545224 BANDAR -Pejabat Kadi Daerah Johor Bahru (ZON 1) 2 UST. FAKHRURAZI BIN YUSOF (791019-01-5805) 013-7270419 3 DATO’ HAJI MAHAT BIN BANDAR -Kg. Tarom -Tmn. Bkt. Saujana MD SAID (ZON 2) -Kg. Bahru -Tmn. Imigresen (360322-01-5539) -Kg. Nong Chik -Tmn. Bakti 07-2240567 -Kg. Mahmodiah -Pangsapuri Sri Murni 019-7254548 -Kg. Mohd Amin -Jln. Petri -Kg. Ngee Heng -Jln. Abd Rahman Andak -Tmn. Nong Chik -Jln. Serama -Tmn. Kolam Air -Menara Tabung Haji -Kolam Air -Dewan Jubli Intan -Jln. Straits View -Jln. Air Molek 4 UST. MOHD SHUKRI BIN BANDAR -Kg. Kurnia -Tmn. Melodies BACHOK (ZON 3) -Kg. Wadi Hana -Tmn. Kebun Teh (780825-01-5275) -Tmn. Perbadanan Islam -Tmn. Century 012-7601408 -Tmn. Suria 5 UST. AYUB BIN YUSOF BANDAR -Kg. Melayu Majidee -Flat Stulang (771228-01-6697) (ZON 4) -Kg. Stulang Baru 017-7286801 1 NAMA JURUNIKAH BI NO KAD PENGENALAN MUKIM KAWASAN L NO TELEFON 6 UST. MOHAMAD BANDAR - Kg. Dato’ Onn Jaafar -Kondo Datin Halimah IZUDDIN BIN HASSAN (ZON 5) - Kg. Aman -Flat Serantau Baru (760601-14-5339) - Kg. Sri Paya -Rumah Pangsa Larkin 013-3352230 - Kg. Kastam -Tmn. Larkin Perdana - Kg. Larkin Jaya -Tmn. Dato’ Onn - Kg. Ungku Mohsin 7 UST. HAJI ABU BAKAR BANDAR -Bandar Baru Uda -Polis Marin BIN WATAK (ZON 6) -Tmn. Skudai Kanan -Kg. -

Peninsular Malaysia & Singapore ›Malaysian

› Peninsular Malaysia & Singapore › Malaysian Borneo & Brunei 8ºN 101ºE S O U T H 102ºE 103ºE 104ºE C H I N A 0 100 km 1500m 1000m 500m 200m 0 0 60 miles S E A VIETNAM PHILIPPINES THAILAND Sabahat Kota Bharu S E A 119ºE Hub of traditional Sabah PENINSULAR BRUNEI ELEVATION Marine Park Tun Sakaran Pulua Mabul P H I L N E S C E L B S Malay culture MALAYSIA Pulau Sipadan MALAYSIAN S E A ’s ginger giants BORNEO S U L Sarawak 7ºN Pulau Sipadan T H A I L A N D Borneo Lahad Datu Archipelago SINGAPORE Sepilok Orang-Utan Rehabilitation Centre Gomantong Caves Sepilok Orang-Utan Rehabilitation Centre 100 km Pulau Langkawi INDONESIA 60 miles Taman Padang Besar Diving jewel of Semporna Sandakan Relax at luxury resorts Semporna Negara INDONESIA Kalimantan Sulawesi 118ºE Perlis PERLIS Sumatra Park Caves Bukit Kayu Madai Hitam Pengkalan Kubor National Pulau Kangar Tawau Java Turtle Islands Pulau Sungai Langkawi Tak Bai Kinabatangan Area Pulau Malawali Cameron Highlands Pulau Banggi Tea plantations and Kota Bharu Jambongan Alor Setar 0 0 pleasant walks Sungai Golok Pulau 6ºN Telupid Conservation Perhentian 117ºE Rantau Panjang Danum Valley Kudat Kinabalu National Park Tambunan KEDAH Pulau Perhentian Danum Valley Pulau Lang Mt Kinabalu (4095m) Maliau Basin Penang Mt 4 Rafflesia Reserve Keroh Tengah Two blissful white-sand- SABAH Pulau Conservation Area National (2640m) and orang-utans Trus Madi Jungle, pygmy elephants Jungle, Park Tasik Redang fringed islands Pulau Sungai Petani Kuala Krai Ranau Temenggor Sikuati 3 Keningau Balambangan Batu Punggul Batu -

SENARAI PREMIS PENGINAPAN PELANCONG : JOHOR 1 Rumah

SENARAI PREMIS PENGINAPAN PELANCONG : JOHOR BIL. NAMA PREMIS ALAMAT POSKOD DAERAH 1 Rumah Tumpangan Lotus 23, Jln Permas Jaya 10/3,Bandar Baru Permas Jaya,Masai 81750 Johor Bahru 2 Okid Cottage 41, Jln Permas 10/7,Bandar Baru Permas Jaya 81750 Johor Bahru 3 Eastern Hotel 200-A,Jln Besar 83700 Yong Peng 4 Mersing Inn 38, Jln Ismail 86800 Mersing 5 Mersing River View Hotel 95, Jln Jemaluang 86800 Mersing 6 Lake Garden Hotel 1,Jln Kemunting 2, Tmn Kemunting 83000 Batu Pahat 7 Rest House Batu Pahat 870,Jln Tasek 83000 Batu Pahat 8 Crystal Inn 36, Jln Zabedah 83000 Batu Pahat 9 Pulai Springs Resort 20KM, Jln Pontian Lama,Pulai 81110 Johor Bahru 10 Suria Hotel No.13-15,Jln Penjaja 83000 Batu Pahat 11 Indah Inn No.47,Jln Titiwangsa 2,Tmn Tampoi Indah 81200 Johor Bahru 12 Berjaya Waterfront Hotel No 88, Jln Ibrahim Sultan, Stulang Laut 80300 Johor Bahru 13 Hotel Sri Pelangi No. 79, Jalan Sisi 84000 Muar 14 A Vista Melati No. 16, Jalan Station 80000 Johor Bahru 15 Hotel Kingdom No.158, Jln Mariam 84000 Muar 16 GBW HOTEL No.9R,Jln Bukit Meldrum 80300 Johor Bahru 17 Crystal Crown Hotel 117, Jln Harimau Tarum,Taman Abad 80250 Johor Bahru 18 Pelican Hotel 181, Jln Rogayah 80300 Batu Pahat 19 Goodhope Hotel No.1,Jln Ronggeng 5,Tmn Skudai Baru 81300 Skudai 20 Hotel New York No.22,Jln Dato' Abdullah Tahir 80300 Johor Bahru 21 THE MARION HOTEL 90A-B & 92 A-B,Jln Serampang,Tmn Pelangi 80050 Johor Bahru 22 Hotel Classic 69, Jln Ali 84000 Muar 23 Marina Lodging PKB 50, Jln Pantai, Parit Jawa 84150 Muar 24 Lok Pin Hotel LC 117, Jln Muar,Tangkak 84900 Muar 25 Hongleng Village 8-7,8-6,8-5,8-2, Jln Abdul Rahman 84000 Muar 26 Anika Inn Kluang 298, Jln Haji Manan,Tmn Lian Seng 86000 Kluang 27 Hotel Anika Kluang 1,3 & 5,Jln Dato' Rauf 86000 Kluang BIL. -

Embassy of Malaysia in Turkmenistan Посольство Малайзии В Туркменистане December 2019

EMBASSY OF MALAYSIA IN TURKMENISTAN ПОСОЛЬСТВО МАЛАЙЗИИ В ТУРКМЕНИСТАНЕ DECEMBER 2019 şgabat GazetY A Newsletter The Embassy of Malaysia in Ashgabat is proud to publish our Newsletter with the news and activities for 2019. Among the highlights of this issue are the Official Visit of the Honourable Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad to Turkmenistan, National Day of Malaysia in Turkmenistan and Malaysia Sports Challenge 2019. Besides that, we will share with you several news from Malaysia and photos of the activities organized or participated by the Embassy. There are also special features about Visit Truly Asia Malaysia 2020 and Shared Prosperity Vision 2030! THE OFFICIAL VISIT OF NATIONAL DAY OF YAB TUN DR. MAHATHIR MALAYSIA IN MALAYSIA SPORTS MOHAMAD TURKMENISTAN AND CHALLENGE 2019 TO TURKMENISTAN MALAYSIA DAY “The many similarities in policies and approaches that exist between Malaysia and Turkmenistan give an opportunity for both countries to work closely together in many areas.” YAB Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad Prime Minister of Malaysia More news on page 2-3 1 EMBASSY OF MALAYSIA IN TURKMENISTAN ПОСОЛЬСТВО МАЛАЙЗИИ В ТУРКМЕНИСТАНЕ DECEMBER 2019 THE OFFICIAL VISIT OF YAB TUN DR. MAHATHIR MOHAMAD PRIME MINISTER OF MALAYSIA TO TURKMENISTAN, 26-28 OCTOBER 2019 YAB Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad undertook an Official Visit to Turkmenistan on 26-28 October 2019 at the invitation of His Excellency Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, the President of Turkmenistan. This is the second Official Visit of YAB Prime Minister to Turkmenistan. He first visited the country in October 1994 when he was the 4th Prime Minister of Malaysia. Meanwhile, President of Turkmenistan had visited Malaysia twice, in December 2011 and November 2016. -

Estimating Mangrove Above-Ground Biomass Loss Due to Deforestation in Malaysian Northern Borneo Between 2000 and 2015 Using SRTM and Landsat Images

Article Estimating Mangrove Above-Ground Biomass Loss Due to Deforestation in Malaysian Northern Borneo between 2000 and 2015 Using SRTM and Landsat Images Charissa J. Wong 1, Daniel James 1, Normah A. Besar 1, Kamlisa U. Kamlun 1, Joseph Tangah 2 , Satoshi Tsuyuki 3 and Mui-How Phua 1,* 1 Faculty of Science and Natural Resources, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Kota Kinabalu 88400, Sabah, Malaysia; [email protected] (C.J.W.); [email protected] (D.J.); [email protected] (N.A.B.); [email protected] (K.U.K.) 2 Sabah Forestry Department, Locked Bag 68, Sandakan 90009, Sabah, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 Graduate School of Agriculture and Life Science, The University of Tokyo, Yayoi 1-1-1, Bunkyo-Ku, Tokyo 113-0032, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 July 2020; Accepted: 26 August 2020; Published: 22 September 2020 Abstract: Mangrove forests are highly productive ecosystems and play an important role in the global carbon cycle. We used Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) elevation data to estimate mangrove above-ground biomass (AGB) in Sabah, Malaysian northern Borneo. We developed a tree-level approach to deal with the substantial temporal discrepancy between the SRTM data and the mangrove’s field measurements. We predicted the annual growth of diameter at breast height and adjusted the field measurements to the SRTM data acquisition year to estimate the field AGB. A canopy height model (CHM) was derived by correcting the SRTM data with ground elevation. Regression analyses between the estimated AGB and SRTM CHM produced an estimation model (R2: 0.61) with 1 a root mean square error (RMSE) of 8.24 Mg ha− (RMSE%: 5.47). -

1380097620-Laporan Tahunan 2003-Bhgn 3

JABATAN ALAM SEKITAR DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT BAB / CHAPTER 5 JABATAN ALAM SEKITAR http://www.jas.sains.my 35 JABATAN ALAM SEKITAR DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT LAPORAN TAHUNAN 2003 36 ANNUAL REPORT 2003 JABATAN ALAM SEKITAR DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT PENGAWASAN KUALITI UDARA AIR QUALITY MONITORING Status Kualiti Udara Air Quality Status Pada tahun 2003, Jabatan Alam Sekitar (JAS) terus In 2003, the Department of Environment (DOE) mengawasi status kualiti udara di dalam negara monitored air quality under the national monitoring melalui rangkaian pengawasan kualiti udara network consisting of 51 automatic and 25 manual kebangsaan yang terdiri dari 51 stesen automatik dan stations (Map 5.1, Map 5.2). Sulphur Dioxide (SO2), 25 stesen manual (Peta 5.1, Peta 5.2). Sulfur Dioksida Carbon Monoxide (CO), Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2), (SO2), Karbon Monoksida (CO), Nitrogen Dioksida Ozone (O3) and Particulate Matter (PM10) were (NO2), Ozon (O3) and Partikulat Terampai (PM10) continuously monitored, while several heavy metals diawasi secara berterusan sementara logam berat including lead (Pb) were measured once in every six termasuk plumbum (Pb) diukur sekali pada setiap days (Table 5.1). enam hari. (Jadual 5.1). Secara keseluruhan, kualiti udara di seluruh negara The overall air quality for Malaysia throughout the pada tahun 2003 meningkat sedikit berbanding tahun 2003 improved slightly compared to 2002, such as sebelumnya terutama bagi parameter Partikulat for PM10, mainly due to more wet weather conditions Terampai (PM10) disebabkan oleh keadaan cuaca -

EARTH SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL Development of Tropical

EARTH SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL Earth Sci. Res. J. Vol. 20, No. 1 (March, 2016): O1 - O10 GEOLOGY ENGINEERING Development of Tropical Lowland Peat Forest Phasic Community Zonations in the Kota Samarahan-Asajaya area, West Sarawak, Malaysia Mohamad Tarmizi Mohamad Zulkifley1, Ng Tham Fatt1, Zainey Konjing2, Muhammad Aqeel Ashraf3,4* 1. Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2. Biostratex Sendirian Berhad, Batu Caves, Gombak, Malaysia. 3. Department of Environmental Science and Engineering, School of Environmental Studies, China University of Geosciences, 430074 Wuhan, P. R. China 4. Faculty of Science & Natural Resources, University Malaysia Sabah88400 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia. Corresponding authors: Muhammad Aqeel Ashraf- Faculty of Science & Natural Resources University Malaysia Sabah, 88400, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Keywords: Lowland peat swamp, Phasic community, Logging observations of auger profiles (Tarmizi, 2014) indicate a vertical, downwards, general decrease of Mangrove swamp, Riparian environment, Pollen peat humification levels with depth in a tropical lowland peat forest in the Kota Samarahan-Asajaya área in the diagram, Vegetation Succession. región of West Sarawak (Malaysia). Based on pollen analyses and field observations, the studied peat profiles can be interpreted as part of a progradation deltaic succession. Continued regression of sea levels, gave rise Record to the development of peat in a transitional mangrove to floodplain/floodbasin environment, followed by a shallow, topogenic peat depositional environment with riparian influence at approximately 2420 ± 30 years B.P. Manuscript received: 20/10/2015 (until present time). The inferred peat vegetational succession reached Phasic Community I at approximately Accepted for publication: 12/02/2016 2380 ± 30 years B.P.