Between Securitisation and Neglect: Managing Ebola at the Borders of Global Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does COVID-19 Take a Breath? the Chinese Current Situation

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 13 April 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202104.0354.v1 Does COVID-19 take a breath? The Chinese Current Situation Abdul Qadeer1#, Muhammad Sohail2#, Ayesha Younas3, Haroon Iqbal4, Asif Ullah5, Hanif Ullah1, Anam Rzzaq4, Bouzid Menaa6, Ijaz ul Haq7, Zulfiqar Ahmed8, Fazle Rabbi9, Nangial Khan10, Faisal Raza11, Saqib Nawaz1, Imran Khan12, Muhammad Izhar ul Haque13, Farid Menaa6* 1Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Key Laboratory of Animal Parasitology of Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Shanghai, China. Email (AQ): [email protected]; Email (HU): [email protected], Email (SN) : [email protected] 2School of Pharmacy, Collaborative Innovation Center of Advanced Drug Delivery System and Biotech Drugs in Universities of Shandong, Key Laboratory of Molecular Pharmacology and Drug Evaluation, Yantai University, China. Email (MS): [email protected] 3College of Pharmaceutical Sciences Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China. Email (AY): [email protected] 4College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Soochow University, Suzhou, China. Email (HI): [email protected] (AR): [email protected] 5School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China. Email (AU): [email protected] 6Department of Nanomedicine, California Innovations Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA. Email (BM): [email protected]; Email (FM): [email protected] 7Jiangsu Food & Pharmaceutical Science College, Huaian, Jiangsu, China. Email (IH): [email protected] 8College of Veterinary Medicine, Sichuan Agriculture University, Chengdu, China. Email (ZA): [email protected] 9Department of Pharmacy, Abasyn University, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Email (FR): [email protected] 10State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology, Institute of Cotton Research of Chinese Academy of Agriculture Sciences, Anyang, China. -

Inside the Ebola Wars the New Yorker

4/13/2017 Inside the Ebola Wars The New Yorker A REPORTER AT LARGE OCTOBER 27, 2014 I﹙UE THE EBOLA WARS How genomics research can help contain the outbreak. By Richard Preston Pardis Sabeti and Stephen Gire in the Genomics Platform of the Broad Institute of M.I.T. and Harvard, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They have been working to sequence Ebola’s genome and track its mutations. he most dangerous outbreak of an emerging infectious disease since the appearance of H.I.V., in the early nineteen-eighties, seems to have begun on DTecember 6, 2013, in the village of Meliandou, in Guinea, in West Africa, with the death of a two-year-old boy who was suffering from diarrhea and a fever. We now know that he was infected with Ebola virus. The virus is a parasite that lives, normally, in some as yet unidentified creature in the ecosystems of equatorial Africa. This creature is the natural host of Ebola; it could be a type of fruit bat, or some small animal that lives on the body of a bat—possibly a bloodsucking insect, a tick, or a mite. Before now, Ebola had caused a number of small, vicious outbreaks in central and eastern Africa. Doctors and other health workers were able to control the outbreaks quickly, and a belief developed in the medical and scientific communities that Ebola was not much of a threat. The virus is spread only through direct contact with blood and bodily fluids, and it didn’t seem to be mutating in any significant way. -

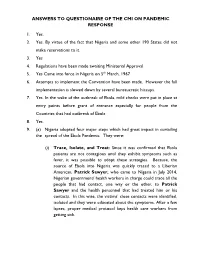

Nigeria MLA Replies to the Pandemic Response Questionnaire

ANSWERS TO QUESTIONAIRE OF THE CMI ON PANDEMIC RESPONSE 1. Yes. 2. Yes. By virtue of the fact that Nigeria and some other 190 States did not make reservations to it. 3. Yes 4. Regulations have been made awaiting Ministerial Approval 5. Yes Came into force in Nigeria on 5th March, 1967 6. Attempts to implement the Convention have been made. However the full implementation is slowed down by several bureaucratic hiccups. 7. Yes. In the wake of the outbreak of Ebola, mild checks were put in place at entry points before grant of entrance especially for people from the Countries that had outbreak of Ebola 8. Yes. 9. (a) Nigeria adopted four major steps which had great impact in curtailing the spread of the Ebola Pandemic. They were: (i) Trace, Isolate, and Treat: Since it was confirmed that Ebola patients are not contagious until they exhibit symptoms such as fever, it was possible to adopt these strategies. Because, the source of Ebola into Nigeria was quickly traced to a Liberian American, Patrick Sawyer, who came to Nigeria in July 2014, Nigerian government/ health workers in charge could trace all the people that had contact, one way or the other, to Patrick Sawyer and the health personnel that had treated him or his contacts. In this wise, the victims’ close contacts were identified, isolated and they were educated about the symptoms. After a few lapses, proper medical protocol kept health care workers from getting sick. (ii) Early Detection before many people could be exposed: It is generally believed that anyone with Ebola, typically, will infect about two more people, unless something is done to intervene. -

Excerpted from the Hot Zone by Richard Preston

The Hot Zone, by Richard Preston - Excerpt The Hot Zone captures the terrifying true story of an Ebola outbreak that made its way from the jungles of Africa to a research lab just outside of Washington, D.C. In the excerpt below, author Richard Preston describes the symptoms of this deadly virus as they appeared in one of its first known human victims. The headache begins, typically, on the seventh day after exposure to the agent. On the seventh day after his New Year’s visit to Kitum cave-January 8, 1980-Monet felt a throbbing pain behind his eyeballs. He decided to stay home from work and went to bed in his bungalow. The headache grew worse. His eyeballs ached, and then his temples began to ache, the pain seeming to circle around inside his head. It would not go away with aspirin, and then he got a severe backache. His housekeeper, Johnnie, was still on her Christmas vacation, and he had recently hired a temporary housekeeper. She tried to take care of him, but she really didn’t know what to do. Then, on the third day after his headache started, he became nauseated, spiked a fever, and began to vomit. His vomiting grew intense and turned into dry heaves. At the same time, he became strangely passive. His face lost all appearance of life and set itself into an expressionless mask, with the eyeballs fixed, paralytic, and staring. The eyelids were slightly droopy, which gave him a peculiar appearance, as if his eyes were popping out of his head and half closed at the same time. -

The Ebola Wars” (P

For Immediate Release: October 20, 2014 Press Contacts: Natalie Raabe, (212) 286-6591 Molly Erman, (212) 286-7936 Ariel Levin, (212) 286-5996 How Genomics Research Can Help Contain the Outbreak In the October 27, 2014, issue of The New Yorker, in “The Ebola Wars” (p. 42), Richard Preston, author of the best-selling book “The Hot Zone”—inspired by a 1992 article he wrote for this magazine—reports from the front lines of American Ebola research, and looks at sci- entists’ efforts to map the genome of the virus. Preston also reports on the quest to save American Ebola survivors Nancy Writebol and Kent Brantly—the first human recipients of the experimental drug ZMapp—and details the tragic loss of Dr. Sheik Humarr Khan, of the Kenema Government Hospital, in Sierra Leone, a specialist in viral hemorrhagic diseases, who died without receiving an experimen- tal treatment. The current Ebola crisis marks “the most dangerous outbreak of an emerging infectious disease since the appearance of H.I.V., in the early nineteen-eighties,” Preston writes. According to Preston, the virus seems to have gone beyond the threshold of out- break and ignited an epidemic. “Right now, the virus’s [genetic] code is changing,” Preston writes. “As Ebola enters a deepening relation- ship with the human species, the question of how it is mutating has significance for every person on earth.” This summer, a team at the Broad Institute of M.I.T. and Harvard, led by Pardis Sabeti, an associate professor of biology at Harvard Uni- versity, sequenced the RNA code of the Ebola strains that lived in the blood of seventy-eight people in and around Kenema during three weeks in May and June, just as the virus was first starting to form chains of infection in Sierra Leone. -

Ebola Virus Misconceptions in College Students

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2016 Development and Validation of Virus and Ebola Misconceptions Assessment (Viremia): Ebola Virus Misconceptions in College Students Michele Miller Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the Immunology and Infectious Disease Commons, and the Microbiology Commons Repository Citation Miller, Michele, "Development and Validation of Virus and Ebola Misconceptions Assessment (Viremia): Ebola Virus Misconceptions in College Students" (2016). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1464. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1464 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF VIRUS AND EBOLA MISCONCEPTIONS ASSESSMENT (VirEMiA): EBOLA VIRUS MISCONCEPTIONS IN COLLEGE STUDENTS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science By MICHELE ELAINE MILLER B.S., University of Indianapolis, 2014 2016 Wright State University COPYRIGHT BY MICHELE ELAINE MILLER 2016 WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL March 17, 2016 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Michele Elaine Miller ENTITLED Development and Validation of Virus and Ebola Misconceptions Assessment (VirEMiA): Ebola Virus Misconceptions in College Students BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science. ___________________________________ William Romine, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Thesis Director ___________________________________ Barbara E. -

Impact of Ebola Virus Disease on School Administration in Nigeria

American International Journal of Contemporary Research Vol. 5, No. 3; June 2015 Impact of Ebola Virus Disease on School Administration in Nigeria Oladunjoye Patrick, PhD Major, Nanighe Baldwin, PhD Niger Delta University Educational Foundations Department Wilberforce Island Bayelsa State Nigeria Abstract This study is focused on the impact of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) on school administration in Nigeria. Two hypothesis were formulated to guide the study. A questionnaire titled Ebola Virus Disease and school administration (EVDSA) was used to collect data. The instrument was administered to one hundred and seventeen (117) teachers and eighty three (83) school administrators randomly selected from the three (3) regions in the federal republic of Nigeria. This instrument was however validated by experts and tested for reliability using the test re-test method and data analyzed using the Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient. The result shows that there is a significant difference between teachers and school heads in urban and rural areas on the outbreak of the EVD. However, there is no significant difference in the perception of teachers and school heads in both urban and rural areas on the effect of EVD on attendance and hygiene in schools. Based on these findings, recommendations were made which include a better information system to the rural areas and the sustenance of the present hygiene practices in schools by school administrators. Introduction The school and the society are knitted together in such a way that whatever affects the society will invariably affect the school. When there are social unrest in the society, the school attendance may be affected. -

The Role of Shed GP in Ebola Virus Pathogenicity Beatriz Escudero Pérez

The role of shed GP in Ebola virus pathogenicity Beatriz Escudero Pérez To cite this version: Beatriz Escudero Pérez. The role of shed GP in Ebola virus pathogenicity. Virology. Ecole normale supérieure de lyon - ENS LYON, 2014. English. NNT : 2014ENSL0933. tel-01340856 HAL Id: tel-01340856 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01340856 Submitted on 2 Jul 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE en vue de l'obtention du grade de Docteur de l’Université de Lyon, délivré par l’École Normale Supérieure de Lyon Discipline : Sciences de la vie Laboratoire Bases Moléculaires de la Pathogénicité Virale École Doctorale de Biologie Moléculaire, Intégrative et Cellulaire présentée et soutenue publiquement le 3 Octobre 2014 par Madame Beatriz Eugenia ESCUDERO PÉREZ _____________________________________________ The role of shed GP in Ebola virus pathogenicity ______________________________________________ Directeur de thèse : M. Viktor VOLCHKOV Devant la commission d'examen formée de : M. Renaud MAHIEUX, Centre International de Recherche en Infectiologie, Président M. Christophe PEYREFITTE, IRBA-ERL, Examinateur M. Daniel PINSCHEWER, University of Basel, Rapporteur M. Viktor VOLCHKOV, Centre International de Recherche en Infectiologie, Directeur de thèse M. Thierry WALZER, Centre International de Recherche en Infectiologie, Examinateur M. -

Order Paper 5 November, 2019

FOURTH REPUBLIC 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FIRST SESSION NO. 54 237 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday 5 November, 2019 1. Prayers 2. National Pledge 3. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 4. Oaths 5. Message from the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 6. Message from the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 7. Messages from Other Parliament(s) (if any) 8. Other Announcements (if any) 9. Petitions (if any) 10. Matter(s) of Urgent Public Importance 11. Personal Explanation ______________________________________________________________ PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Federal College of Agriculture, Katcha, Niger State (Establishment) Bill, 2019 (HB.403) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 2. Public Service Efficiency Bill, 2019 (HB.404) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 3. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 (HB.405) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 4. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 ((HB.406) (Hon. Dachung Musa Bagos) – First Reading. 5. National Rice Development Council Bill, 2019 (HB.407) (Hon. Saidu Musa Abdullahi) – First Reading. 238 Tuesday 5 November, 2019 No. 54 6. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 (HB.408) (Hon. Dachung Musa Bagos) – First Reading. 7. Counselling Practitioners Council of Nigeria (Establishment) Bill, 2019 (HB.409) (Hon. Muhammad Ali Wudil) – First Reading. 8. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Alteration) Bill, 2019 (HB.410) (Hon. Dachung Musa Bagos) – First Reading. 9. Federal University of Medicine and Health Services, Bida, Niger State (Establishment) Bill, 2019 (HB.411) (Hon. -

What We Can Learn from and About Africa in the Corona Crisis The

Pockets of effectiveness What we can learn from and about Africa in the corona crisis by Michael Roll, German Development Institute / D eutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) The Current Column of 2 April 2020 Pockets of effectiveness What we can learn from and about Africa in the corona crisis Is Africa defenceless in the face of the corona pandemic? This to a treatment centre. In total, 20 people became infected in would appear to be self-evident, as even health care systems Nigeria in 2014 and eight of them died. The WHO lauded the far better equipped than those of many African countries are successful contact-tracing work under very difficult condi- currently on the verge of collapse. Nonetheless, such a con- tions as a piece of “world-class epidemiological detective clusion is premature. In part, some African countries are work”. even better prepared for pandemics than Europe and the What does this mean for corona in Nigeria and in Africa? As a United States. Nigeria’s success in fighting its 2014 Ebola result of their experience with infectious diseases, many Afri- outbreak illustrates why that is the case and what lessons can countries have established structures for fighting epidem- wealthier countries and the development cooperation com- ics in recent years. These measures and the continent’s head munity can learn from it. start over other world regions are beneficial for tackling the Learning from experience corona pandemic. However, this will only help at an early stage when the chains of infection can still be broken by iden- Like other African countries, Nigeria has experience in deal- tifying and isolating infected individuals. -

BY the TIME YOU READ THIS, WE'll ALL BE DEAD: the Failures of History and Institutions Regarding the 2013-2015 West African Eb

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2015 BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic. George Denkey Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Denkey, George, "BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic.". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2015. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/517 BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS, WE’LL ALL BE DEAD: The failures of history and institutions regarding the 2013-2015 West African Ebola Pandemic. By Georges Kankou Denkey A Thesis Submitted to the Department Of Urban Studies of Trinity College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts Degree 1 Table Of Contents For Ameyo ………………………………………………..………………………........ 3 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………………. 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………… 6 Ebola: A Background …………………………………………………………………… 20 The Past is a foreign country: Historical variables behind the spread ……………… 39 Ebola: The Detailed Trajectory ………………………………………………………… 61 Why it spread: Cultural -

{PDF} the Hot Zone Ebook, Epub

THE HOT ZONE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Preston | 448 pages | 01 Aug 1995 | Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc | 9780385479561 | English | New York, United States The Hot Zone PDF Book Kyle Orman 6 episodes, James D'Arcy Both species, the human and the monkey, were in the presence of another life form, which was older and more powerful than either of them, and was a dweller in blood. Yes this is history written in the style of journalism and therefor for popular consumption. However I don't think it's crazy that the "winner" of viruses vs. That is a simple statement and around it revolves the larger story. The depth of research is apparent and thorough and while I did feel like I was learning while being A very scary and fast paced read that is all the more terrifying because it is true. This book continued to fuel the emerging diseases campaign. Jones reveals that at the time of the Marburg outbreak, he was inspecting monkeys in Entebbe that were to be exported to Europe. By thirty percent. Jahrling's analysis races up the chain of command. Retrieved July 31, Ben's Young Son 1 2 episodes, Later, while working on a dead monkey infected with Ebola virus, one of the gloves on the hand with the open wound tears, and she is almost exposed to contaminated blood, but does not get infected. Lloviu cuevavirus LLOV. Shem Musoke. The monster has not been slain and the good guys at best can regain some control. So totally pure. As she develops symptoms, Nurse Mayinga fears that her scholarship to study in Europe might be revoked.