Inquiry Into the Proposed Lease of the Port of Melbourne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorian Heritage Database Place Details - 1/1/2014 Darbyshire Hill No.1 & No

Victorian Heritage Database place details - 1/1/2014 Darbyshire Hill No.1 & No. 2 Bridges Location: Wodonga-Cudgewa Railway, midway between Bullioh & Darbyshire, BULLIOH, TOWONG SHIRE Heritage Inventory (HI) Number: 1 Listing Authority: HI Extent of Registration: Statement of Significance: Darbyshire Hill Nos. 1 and 2 Bridges are single-track rail bridges of three-storey pier design and combine standard fifteen feet timber-beam approach spans with twenty feet rolled-steel-joist spans over the main channels. The timber piers on these bridges are fitted with rare double-longitudinal walings. No. 2: timber and steel composite rail bridge 96.6 metres (317 feet) long, with unusually tall 4 pile timber piers (max. height, 21.3 metres, 79 feet), six timber-beam approach spans each of fifteen feet (4.6 metres), eleven rolled-steel-joist spans each of twenty feet (6.1 metres), and a straight deck of standard transverse-timber design. This bridge, 21.3 metres high, is the tallest railway bridge of timber and steel joist construction to survive in Victoria. No. 1 timber and steel composite rail bridge 65.48 metres (215 feet) long, with unusually tall 4 pile timber piers (max. height, 16.45 metres, 54 feet), and a curving transverse-timber deck. This bridge has five timber-beam spans each of standard fifteen feet (4.6 metre) Victorian Railways design, and seven rolled-steel-joist spans each of twenty feet (6.1 metres). Darbyshire Hill Nos.1 and 2 Bridges were built in 1916 as part of the Wodonga-Cudgewa railway. The line was closed in 1981. -

Regional Development Victoria Regional Development Victoria

Regional Development victoRia Annual Report 12-13 RDV ANNUAL REPORT 12-13 CONTENTS PG1 CONTENTS Highlights 2012-13 _________________________________________________2 Introduction ______________________________________________________6 Chief Executive Foreword 6 Overview _________________________________________________________8 Responsibilities 8 Profile 9 Regional Policy Advisory Committee 11 Partners and Stakeholders 12 Operation of the Regional Policy Advisory Committee 14 Delivering the Regional Development Australia Initiative 15 Working with Regional Cities Victoria 16 Working with Rural Councils Victoria 17 Implementing the Regional Growth Fund 18 Regional Growth Fund: Delivering Major Infrastructure 20 Regional Growth Fund: Energy for the Regions 28 Regional Growth Fund: Supporting Local Initiatives 29 Regional Growth Fund: Latrobe Valley Industry and Infrastructure Fund 31 Regional Growth Fund: Other Key Initiatives 33 Disaster Recovery Support 34 Regional Economic Growth Project 36 Geelong Advancement Fund 37 Farmers’ Markets 37 Thinking Regional and Rural Guidelines 38 Hosting the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development 38 2013 Regional Victoria Living Expo 39 Good Move Regional Marketing Campaign 40 Future Priorities 2013-14 42 Finance ________________________________________________________ 44 RDV Grant Payments 45 Economic Infrastructure 63 Output Targets and Performance 69 Revenue and Expenses 70 Financial Performance 71 Compliance 71 Legislation 71 Front and back cover image shows the new $52.6 million Regional and Community Health Hub (REACH) at Deakin University’s Waurn Ponds campus in Geelong. Contact Information _______________________________________________72 RDV ANNUAL REPORT 12-13 RDV ANNUAL REPORT 12-13 HIGHLIGHTS PG2 HIGHLIGHTS PG3 September 2012 December 2012 > Announced the date for the 2013 Regional > Supported the $46.9 million Victoria Living Expo at the Good Move redevelopment of central Wodonga with campaign stand at the Royal Melbourne $3 million from the Regional Growth Show. -

Independent Review of the Victorian Ports System: Discussion Paper

Independent review of the Victorian Ports System DISCUSSION PAPER JULY 2020 Department of Transport Authorised by the Victorian Government, Melbourne 1 Spring Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Telephone (03) 9655 6666 Designed and published by the Department of Transport ISBN 978-0-7311-9179-6 Contact us if you need this information in an accessible format such as large print or audio, please telephone (03) 9655 6666 or email [email protected] © Copyright State of Victoria Department of Transport Except for any logos, emblems, trademarks, artwork and photography this document is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence Contents Minister's Foreword 4 6. Safe operation of the port system 40 Preface 5 6.1. Introduction 40 Abbreviations 6 6.2. Issues and options 42 1. Introduction 7 6.2.1. Harbour Masters 42 1.1. The purpose of the review 7 6.2.2. Pilotage 43 1.2. The review approach 7 6.2.3. Towage 46 1.3. Review process and timing 8 6.2.4. Safety and Environment 47 Management Plans 2. The Victorian Ports System 10 6.2.5. A port safety licensing system 49 2.1. The recent evolution of the system 10 7. Port strategic planning 53 2.2. The system today 12 7.1. Introduction 53 2.2.1. Commercial ports 14 7.2. Issues and options 54 2.2.2. Local ports 15 7.2.1. Port Development Strategies 54 3. A Vision for the Victorian Ports 19 System 7.2.2. A Victorian ports strategy 55 3.1. -

Relevant Project Experience

RELEVANT PROJECT EXPERIENCE Aquatic Feasibility and Facility Projects Hydrotherapy Feasibility - City of Bayside Guidelines for Outdoor Seasonal Pools - Maintenance, Retrofitting, Refurbishment & Re-Building Input - Aquatics Gosford Olympic Pool Feasibility and Design Concept - Central Recreation Victoria Coast Council Corryong Swimming Pool Master Plan - Shire of Towong Aquatic Facility Design Concept - Shire of Moorabool Corroyong Swimming Pool Coomunity Engagement - Shire of Aquatics Feasibility Study - Shire of Moorabool Towong Mildura Waves Competitive Neutrality Review - Mildura Rural City Newman Recreation Facilities Master Plan (including aquatic Whittlesea Swimming Pool Upgrade Feasibility - City of Whittle- facilities) - Shire of East Pilbara sea Business Case and Concept for a Kununurra Aquatic and Hydrotherapy Facility Feasibility - Shire of Campaspe Leisure Facility - City of Wyndham Management of the Operation of the Swimming Pools 2017-2018 Business Case and Feasibility - Tweed Regional Sports - West Coast Council Centre (including aquatic centre) - Tweed Shire West Coast Aquatic Facilities Strategy - West Coast Council Business and Marketing Plan for a new Aquatic Centre - City of Orange Portland Leisure and Aquatic Centre Feasibility Study - including Business Plan and Concept Design - Shire of Glenelg Regional Aquatic and Netball Precinct Feasibility and Master plan - Yarra Ranges Shire Short Term Aquatic Demand Strategy - City of Wyndham Aquatic Facility Development Strategy and Strategic Technical Review of Seymour -

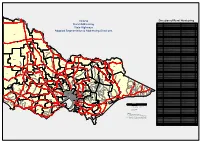

Victoria Rural Addressing State Highways Adopted Segmentation & Addressing Directions

23 0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 MILDURA Direction of Rural Numbering 0 Victoria 00 00 Highway 00 00 00 Sturt 00 00 00 110 00 Hwy_name From To Distance Bass Highway South Gippsland Hwy @ Lang Lang South Gippsland Hwy @ Leongatha 93 Rural Addressing Bellarine Highway Latrobe Tce (Princes Hwy) @ Geelong Queenscliffe 29 Bonang Road Princes Hwy @ Orbost McKillops Rd @ Bonang 90 Bonang Road McKillops Rd @ Bonang New South Wales State Border 21 Borung Highway Calder Hwy @ Charlton Sunraysia Hwy @ Donald 42 99 State Highways Borung Highway Sunraysia Hwy @ Litchfield Borung Hwy @ Warracknabeal 42 ROBINVALE Calder Borung Highway Henty Hwy @ Warracknabeal Western Highway @ Dimboola 41 Calder Alternative Highway Calder Hwy @ Ravenswood Calder Hwy @ Marong 21 48 BOUNDARY BEND Adopted Segmentation & Addressing Directions Calder Highway Kyneton-Trentham Rd @ Kyneton McIvor Hwy @ Bendigo 65 0 Calder Highway McIvor Hwy @ Bendigo Boort-Wedderburn Rd @ Wedderburn 73 000000 000000 000000 Calder Highway Boort-Wedderburn Rd @ Wedderburn Boort-Wycheproof Rd @ Wycheproof 62 Murray MILDURA Calder Highway Boort-Wycheproof Rd @ Wycheproof Sea Lake-Swan Hill Rd @ Sea Lake 77 Calder Highway Sea Lake-Swan Hill Rd @ Sea Lake Mallee Hwy @ Ouyen 88 Calder Highway Mallee Hwy @ Ouyen Deakin Ave-Fifteenth St (Sturt Hwy) @ Mildura 99 Calder Highway Deakin Ave-Fifteenth St (Sturt Hwy) @ Mildura Murray River @ Yelta 23 Glenelg Highway Midland Hwy @ Ballarat Yalla-Y-Poora Rd @ Streatham 76 OUYEN Highway 0 0 97 000000 PIANGIL Glenelg Highway Yalla-Y-Poora Rd @ Streatham Lonsdale -

Victoria Regio

VICTORIA. ANNO QUADRAGESIMO TERTIO VICTORIA REGIO. No. DCLIV. An Act to apply a sum out of the Consolidated Revenue to the service of the year ending on the last day of June One thousand eight hundred and eighty and to appropriate the Supplies granted in this Session of Parliament. [5th February 1880.] MOST GRACIOUS SOVEREIGN— E Your Mai esty's most dutiful and loyal subjects the Legislative Preamble. W Assembly of Victoria in Parliament assembled towards making good the supply which we have cheerfully granted to Your Majesty in this session of Parliament have resolved to grant unto Your Majesty the sums hereinafter mentioned and do therefore most humblv beseech Your Majesty that it may be enacted And be it enacted by the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty by and with the advice and consent of the Legis lative Council and the Legislative Assembly of Victoria in this present Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same as follows:— 1. Out of the Consolidated Revenue there shall and may be Application of issued and applied for or towards making good the supply granted to mone>rs Her Majesty a sum not exceeding One million seven hundred and seventy- .£1,779,772. nine thousand seven hundred and seventy-two pounds for the service of the year ending on the thirtieth dav of June One thousand eight hundred and eighty. 2. All sums granted by this Act and the other Acts mentioned Appropriation of in the First Schedule annexed to this Act out of the said Consolidated _SuJ^es; First Selie-liilc, Revenue towards making irood the supply granted to Her Majestv amounting" Published as a Supplement to the c Victoria Government Gazette' of Friday, 6th February JSKO. -

Duke's & Orr's Dry Dock Pump House, Melbourne, Victoria

Engineers Australia Engineering Heritage Victoria Nomination Engineering Heritage Australia Heritage Recognition Program DUKE’S & ORR’S DRY DOCK PUMP HOUSE, MELBOURNE , VICTORIA May 2014 2 Front Cover Photograph Caption “The way it was in the 1940s through the eyes of a shipwright. Melbourne photographer Jack Cato captured the atmosphere of the dry dock in this study of the entrance to Duke’s & Orr’s in the 1940s. The mitre gates are closed and pumping out is well under way”. Image: Jack Cato. Reproduced at page ix of Arthur E Woodley and Bob Botterill’s book Duke’s & Orr’s Dry Dock. The caption is also taken from the book with thanks to the authors. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Table of Contents 3 1 Introduction 5 2 Heritage Nomination Letter 7 3 Heritage Assessment 8 3.1 Item Name 8 3.2 Other/Former Names 8 3.3 Location 8 3.4 Address: 8 3.5 Suburb/Nearest Town 8 3.6 State 8 3.7 Local Govt. Area 8 3.8 Owner 8 3.10 Former Use 8 3.11 Designer 8 3.12 Maker/Builder 8 3.13 Year Started 8 3.14 Year Completed 8 3.15 Physical Description 8 3.16 Physical Condition 9 3.17 Modifications and Dates 9 3.18 Historical Notes 12 3.19 Heritage Listings 17 4 Assessment of Significance 18 4.1 Historical significance 18 4.2 Historic Individuals or Association 18 4.3 Creative or Technical Achievement of the Pump House 20 4.4 Research Potential of the dry dock and Pump House 20 4.5 Social Significance of the dry dock 21 4.6 Rarity relating to the dry dock and Pump House 21 4.7 Representativeness of the Pump House pumping machinery 23 4.8 Integrity/Intactness of -

Australian Historic Theme: Producers

Stockyard Creek, engraving, J MacFarlane. La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria. Gold discoveries in the early 1870s stimulated the development of Foster, initially known as Stockyard Creek. Before the railway reached Foster in 1892, water transport was the most reliable method of moving goods into and out of the region. 4. Moving goods and cargo Providing transport networks for settlers on the land Access to transport for their produce is essential to primary Australian Historic Theme: producers. But the rapid population development of Victoria in the nineteenth century, particularly during the 1850s meant 3.8. Moving Goods and that infrastructure such as good all-weather roads, bridges and railway lines were often inadequate. Even as major roads People were constructed, they were often fi nanced by tolls, adding fi nancial burden to farmers attempting to convey their produce In the second half of the nineteenth century a great deal of to market. It is little wonder that during the 1850s, for instance, money and government effort was spent developing port and when a rapidly growing population provided a market for grain, harbour infrastructure. To a large extent, this development was fruit and vegetables, most of these products were grown linked to efforts to stimulate the economic development of the near the major centres of population, such as near the major colony by assisting the growth of agriculture and settlement goldfi elds or close to Melbourne and Geelong. Farmers with on the land. Port and harbour development was also linked access to water transport had an edge over those without it. -

To Owon Ng S Hire E Cou Unci L

TOOWONG SHIRE COUNCIL Decision on application for a higher cap for 2016-17 May 2016 An appropriate citation for this paper is: Essential Services Commission 2016, Towong Shire Council — Decision on application for a higher cap for 2016-17, May. ESSENTIAL SERVICES COMMISSION. THIS PUBLICATION IS COPYRIGHT. NO PART MAY BE REPRODUCED BY ANY PROCESS EXCEPT IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE PROVISIONS OF THE COPYRIGHT ACT 1968 AND THE PERMISSION OF THE ESSENTIAL SERVICES COMMISSION. CONTENTS 1. OUR DECISION 1 2. WHAT DID THE COUNCIL APPLY FOR AND WHY? 3 3. HOW DID WE REACH OUR DECISION? 4 APPENDIX A: SUMMARY OF COMMUNICATIONS WITH TOWONG 10 APPENDIX B: LGPRF INDICATOR DEFINITIONS 11 ESSENTIAL SERVICES COMMISSION DECISION ON APPLICATION FOR A HIGHER CAP 2016-17 III VICTORIA TOWONG SHIRE COUNCIL 1. OUR DECISION The Fair Go Rates System (FGRS), established in the Local Government Act 1989 (the Act), requires local councils to limit their average annual rate increases to a rate cap, determined annually by the Minister for Local Government (the Minister).1 For the 2016-17 rating year, the cap has been set at 2.5 per cent. Councils wishing to increase their average annual rates by more than 2.5 per cent in 2016-17 must first obtain approval from the Essential Services Commission (the Commission). We are responsible for approving, rejecting or approving in part the higher cap sought by a council. This paper outlines our decision in response to an application by Towong Shire Council (Towong) for a higher cap of 6.34 per cent (which includes the Minister’s rate cap of 2.5 per cent) to apply in 2016-17. -

Fortieth Annual Report

1953-54 VICTORIA COUNTRY ROADS BOARD FORTIETH ANNUAL REPORT FOR YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE, 1953 PHESE~TIW TO BOTH HOUSEIS OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO ACT No. 3662. (Approximate Cosl of !1Pport. -Preparathm) not given. PTinting Or058 copies), .t;55(L) !'Jl ~ uthotttu W. M. HOUSTON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE:. No. -!.-[3s. 6d.J--l0750;53. FORMER BOARD MEMBERS. W. CALDER Chairman, 1913-1928. W. T. B. McCORMACK, F. W. FRICKE, A. E. CALLAWAY, Member - 1913-1928. Member - 1913-1938. Chief Engineer 1913-1928. Chairman 1928-1938. Chairman 1938-1940. Member - • 1928-1929. W. L. DALE, A. D. MACKENZIE, L. F. LODER, Secretary 1913-1929. Member - • 1938-1940. Chief Engineer 1928-1940. Member • 1929-1945. Chairman 1940-1944. Chairman 1945-1949, COUNTRY ROADS BOARD FORTIETH ANNUAL REPORT 1953 CONTENTS RETROSPECT- The origin and tasks of the Board in 1018 7 Early investigations ll Growth of Board's responsibilitie" 9 Co-operation with Municipaliti0,.. ~~ Present-day expemliture 10 f<'INANCE- Inadequacy of funds for present needs 10 Detel'im·ation of road paYement::; and bJ·idges 10 Allocation of funds 1952-53 10 Heceipts from Motor Registmtion Fee" 13 Commonwealth Aid Roac1;, Ad 13 Loan Moneys expenditure 13 Total lVorks Allocation>< H ]\[ AIN ROADS-- Allocation of J:'und"" 14 Apportionment of Cost>< 14 Contr-ibutions by Municipal ( 'ouncils 17 Summary of \\'m·ks I i :-ITATFJ HwHWAY~- Restricted Allocation of Funds w \Vorkl" car1•il'd out 19 TounrsTH' HoADH Allocation of ·Fund>< \Vorks carried out FOREST ROADS- Expendit·Ul'e and extent of work l'NCLASSIFIED ROAD~- Applications from Councils for Grants 24 Allocations for :\:laintenancP 24 \Vorks carried out 24 HRIDGES·- Hate of Reconstructiou 25 Bridges completed during year 25 Metropolitan Bridges 2fi FLOOD DA:UAGE-·-- Government Assistance 3lj Grants to Municipalitiei> 83 He,;toraUon \Vorks cai•ricd out 33 \VORK FOR OTHER AFTHORTTIE.;· Housing Commission 37 Rtatc Hivers and \Vater Supply ConuniflHion 87 Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of \Vorks 38 State Electricity Commission 38 Department of Publie Works . -

Victoria Harbour Docklands Conservation Management

VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Places Victoria & City of Melbourne June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi PROJECT TEAM xii 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background and brief 1 1.2 Melbourne Docklands 1 1.3 Master planning & development 2 1.4 Heritage status 2 1.5 Location 2 1.6 Methodology 2 1.7 Report content 4 1.7.1 Management and development 4 1.7.2 Background and contextual history 4 1.7.3 Physical survey and analysis 4 1.7.4 Heritage significance 4 1.7.5 Conservation policy and strategy 5 1.8 Sources 5 1.9 Historic images and documents 5 2.0 MANAGEMENT 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Management responsibilities 7 2.2.1 Management history 7 2.2.2 Current management arrangements 7 2.3 Heritage controls 10 2.3.1 Victorian Heritage Register 10 2.3.2 Victorian Heritage Inventory 10 2.3.3 Melbourne Planning Scheme 12 2.3.4 National Trust of Australia (Victoria) 12 2.4 Heritage approvals & statutory obligations 12 2.4.1 Where permits are required 12 2.4.2 Permit exemptions and minor works 12 2.4.3 Heritage Victoria permit process and requirements 13 2.4.4 Heritage impacts 14 2.4.5 Project planning and timing 14 2.4.6 Appeals 15 LOVELL CHEN i 3.0 HISTORY 17 3.1 Introduction 17 3.2 Pre-contact history 17 3.3 Early European occupation 17 3.4 Early Melbourne shipping and port activity 18 3.5 Railways development and expansion 20 3.6 Victoria Dock 21 3.6.1 Planning the dock 21 3.6.2 Constructing the dock 22 3.6.3 West Melbourne Dock opens -

West Gate Tunnel Project Preliminary Matters and Further Information

Inquiry and Advisory Committee West Gate Tunnel Project Preliminary Matters and Further Information Request Front page 18 July 2017 Preliminary Matters and Further Information Request General Declaration: This information is sought for clarification and is sought without prejudice to the final recommendations of the Inquiry and Advisory Committee (IAC). The Western Distributor Authority (WDA) and other parties should not assume that the issues raised in this request for information are the only issues of interest to the IAC or that the IAC has particular concerns about these issues. The IAC reserves the right to seek further information as necessary throughout the course of the Public Hearing process. The issues raised in this report do not represent any, or the only, opinions of the IAC. 18 July 2017 Nick Wimbush, Chair West Gate Tunnel Project | Preliminary Matters and Further Information Request | 18 July 2017 Contents Page 1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 1. Background .............................................................................................................. 1 2. Purpose of this document ....................................................................................... 1 3. The IAC and Technical Advisers ............................................................................... 1 2 Traffic and Transport .................................................................................................2 1. Port Access