NEW Moma OPENS with a DYNAMIC PRESENTATION of ARCHITECTURE and DESIGN ACROSS ALL FLOORS of the MUSEUM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Seeing and Being Seen

ON SEEING AND BEING SEEN BY MEG MILLER As one designer goes blind, another emerges from under his shadow EyeOnDesign_#01_Mag-6.5x9in_160pgs_PRINT.indd 52 2/13/18 2:49 PM ALVIN LUSTIG AND ELAINE LUSTIG COHEN. COURTESY: THE ESTATE OF ELAINE LUSTIG COHEN BY MEG MILLER As one designer goes blind, another emerges from under his shadow Pages 52 and 53 EyeOnDesign_#01_Mag-6.5x9in_160pgs_PRINT.indd 53 2/13/18 2:49 PM On Amazon, you can buy a new, because he no longer saw them. hardbound copy of Tennessee Instead, he would verbally dictate Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof for what he imagined in his mind’s $1,788.01. The play is one of Williams’ eye to Elaine and the assistants most famous, and allegedly his working at his design office. personal favorite. But the reason “He would tell us go down a behind the price tag is more likely pica and over three picas, and how the cover than its contents; a milky high the type should be, and what galaxy wraps around the spine, the color should be,” said Elaine. and the monosyllabic words of Sometimes his reference points the title stack up the center like a were past projects—“the beige that chimney. At a talk in 2013, Elaine we used on such and such”—or the Lustig Cohen, who was widowed by colors of furniture he’d picked out the book’s famous designer, Alvin for interior jobs. In one particularly Lustig, turned to Steven Heller, her poetic instance, he described the interviewer on stage. -

Acquisitions 2017–18

Acquisitions 2017–18 1 Architecture and Design A total of 544 works were acquired by the Department of Architecture and Design. This includes 71 architecture works and 473 design works. Architectural Drawings Design Earth. Rania Ghosn. El Hadi Jazairi. After Oil (Bubian: There Once Was an Island). 2016. Inkjet Archi‑Union Architects. Philip F. Yuan. Chi She, Shanghai, print on canvas, 27 9⁄1₆ × 27 9⁄1₆ × 1³⁄1₆" (70 × 70 × 2 cm). China. 2017. Wood, steel, and concrete, overall Fund for the Twenty‑First Century (approx): 57 × 51 × 37 ½"; model only: 15 ½ × 37 ½ × 18 ½". Committee on Architecture and Design Funds Anupama Kundoo. Wall House, Auroville, India. 1997–2000. Model, 9 1³⁄1₆ × 23 ⅝ × 23 ⅝" (25 × 60 × Archi‑Union Architects. Philip F. Yuan. “In Bamboo” 60 cm). Fund for the Twenty‑First Century Cultural Exchange Center, Daoming, Sichuan Province, China. 2017. Wood, steel, and bamboo, Anupama Kundoo. Wall House, Auroville, India. 1997– overall (approx.) 62 × 50 × 36"; model only: 21 × 50 × 2000. Ink on paper, 24 7⁄1₆ × 24 7⁄1₆" (62 × 62 cm). Fund 36". Committee on Architecture and Design Funds for the Twenty‑First Century Design Earth. Rania Ghosn. El Hadi Jazairi. After Oil Anupama Kundoo. Wall House, Auroville, India. (Das Island, Das Crude). 2016. Inkjet print on canvas, 1997–2000. Ink on paper, 10 ⅝ × 24 7⁄1₆" (27 × 62 cm). 27 9⁄1₆ × 27 9⁄1₆ × 1³⁄1₆" (70 × 70 × 2 cm). Fund for the Fund for the Twenty‑First Century Twenty‑First Century Anupama Kundoo. Wall House, Auroville, India. Design Earth. Rania Ghosn. El Hadi Jazairi. -

Oral History Interview with Rachel Adler, 2009 June 18-23

Oral history interview with Rachel Adler, 2009 June 18-23 Funding for this interview was provided by the Art Dealers Association of America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Rachel Adler on 2009 June 18- 23. The interview took place at Adler's home in New York, NY, and was conducted by James McElhinney for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Funding for this interview was provided by a grant from the Art Dealers Association of America. Rachel Adler has reviewed the transcript and has made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JAMES McELHINNEY: This is James McElhinney speaking with Rachel Adler on June 18, 2009, at 1200 Broadway in New York City. A lovely place. RACHEL ADLER: Thank you. MR. McELHINNEY: You had an architect, I imagine. MS. ADLER: Oh, yes. Yes, but 30 years ago. MR. McELHINNEY: Oh, really. MS. ADLER: Yes. MR. McELHINNEY: Who was it? MS. ADLER: Carmi Bee. MR. McELHINNEY: Carmi Bee. MS. ADLER: Yes. MR. McELHINNEY: It's a wonderful space. MS. ADLER: It was complicated because the beams are very strong, and they're always present visually. MR. McELHINNEY: Right. -

California Design, 1930-1965: “Living in a Modern Way” CHECKLIST

^ California design, 1930-1965: “living in a modern way” CHECKLIST 1. Evelyn Ackerman (b. 1924, active Culver City) Jerome Ackerman (b. 1920, active Culver City) ERA Industries (Culver City, 1956–present) Ellipses mosaic, c. 1958 Glass mosaic 12 3 ⁄4 x 60 1 ⁄2 x 1 in. (32.4 x 153.7 x 2.5 cm) Collection of Hilary and James McQuaide 2. Acme Boots (Clarksville, Tennessee, founded 1929) Woman’s cowboy boots, 1930s Leather Each: 11 1 ⁄4 x 10 1⁄4 x 3 7⁄8 in. (28.6 x 26 x 9.8 cm) Courtesy of Museum of the American West, Autry National Center 3. Allan Adler (1916–2002, active Los Angeles) Teardrop coffeepot, teapot, creamer and sugar, c. 1957 Silver, ebony Coffeepot, height: 10 in. (25.4 cm); diameter: 9 in. (22.7 cm) Collection of Rebecca Adler (Mrs. Allan Adler) 4. Gilbert Adrian (1903–1959, active Los Angeles) Adrian Ltd. (Beverly Hills, 1942–52) Two-piece dress from The Atomic 50s collection, 1950 Rayon crepe, rayon faille Dress, center-back length: 37 in. (94 cm); bolero, center-back length: 14 in. (35.6 cm) LACMA, Gift of Mrs. Houston Rehrig 5. Gregory Ain (1908–1988, active Los Angeles) Dunsmuir Flats, Los Angeles (exterior perspective), 1937 Graphite on paper 9 3 ⁄4 x 19 1⁄4 in. (24.8 x 48.9 cm) Gregory Ain Collection, Architecture and Design Collection, Museum of Art, Design + Architecture, UC Santa Barbara 6. Gregory Ain (1908–1988, active Los Angeles) Dunsmuir Flats, Los Angeles (plan), 1937 Ink on paper 9 1 ⁄4 x 24 3⁄8 in. -

FALL 2021 COURSE BULLETIN School of Visual Arts Division of Continuing Education Fall 2021

FALL 2021 COURSE BULLETIN School of Visual Arts Division of Continuing Education Fall 2021 2 The School of Visual Arts has been authorized by the Association, Inc., and as such meets the Education New York State Board of Regents (www.highered.nysed. Standards of the art therapy profession. gov) to confer the degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts on graduates of programs in Advertising; Animation; The School of Visual Arts does not discriminate on the Cartooning; Computer Art, Computer Animation and basis of gender, race, color, creed, disability, age, sexual Visual Effects; Design; Film; Fine Arts; Illustration; orientation, marital status, national origin or other legally Interior Design; Photography and Video; Visual and protected statuses. Critical Studies; and to confer the degree of Master of Arts on graduates of programs in Art Education; The College reserves the right to make changes from Curatorial Practice; Design Research, Writing and time to time affecting policies, fees, curricula and other Criticism; and to confer the degree of Master of Arts in matters announced in this or any other publication. Teaching on graduates of the program in Art Education; Statements in this and other publications do not and to confer the degree of Master of Fine Arts on grad- constitute a contract. uates of programs in Art Practice; Computer Arts; Design; Design for Social Innovation; Fine Arts; Volume XCVIII number 3, August 1, 2021 Illustration as Visual Essay; Interaction Design; Published by the Visual Arts Press, Ltd., © 2021 Photography, Video and Related Media; Products of Design; Social Documentary Film; Visual Narrative; and to confer the degree of Master of Professional Studies credits on graduates of programs in Art Therapy; Branding; Executive creative director: Anthony P. -

Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: the Avant-Garde, No

NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J BATA LIBRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/raoulhausmannberOOOObens Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: The Avant-Garde, No. 55 Stephen C. Foster, Series Editor Associate Professor of Art History University of Iowa Other Titles in This Series No. 47 Artwords: Discourse on the 60s and 70s Jeanne Siegel No. 48 Dadaj Dimensions Stephen C. Foster, ed. No. 49 Arthur Dove: Nature as Symbol Sherrye Cohn No. 50 The New Generation and Artistic Modernism in the Ukraine Myroslava M. Mudrak No. 51 Gypsies and Other Bohemians: The Myth of the Artist in Nineteenth- Century France Marilyn R. Brown No. 52 Emil Nolde and German Expressionism: A Prophet in His Own Land William S. Bradley No. 53 The Skyscraper in American Art, 1890-1931 Merrill Schleier No. 54 Andy Warhol’s Art and Films Patrick S. Smith Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada by Timothy O. Benson T TA /f T Research U'lVlT Press Ann Arbor, Michigan \ u » V-*** \ C\ Xv»;s 7 ; Copyright © 1987, 1986 Timothy O. Benson All rights reserved Produced and distributed by UMI Research Press an imprint of University Microfilms, Inc. Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Benson, Timothy O., 1950- Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada. (Studies in the fine arts. The Avant-garde ; no. 55) Revision of author’s thesis (Ph D.)— University of Iowa, 1985. Bibliography: p. Includes index. I. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Aesthetics. 2. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Political and social views. -

Avant-Garde and Contemporary Art Books & Ephemera

Avant-garde and Contemporary Art Books & Ephemera Sanctuary Books [email protected] (212) 861-1055 2 [Roh, Franz and Jan Tschichold] foto-auge / oeil et photo / photo-eye. Akademischer Verlag Dr. Fritz Wedekind & Co., Stuttgart, 1929. Paperback. 8.25 x 11.5”. Condition: Good. First Edition. 76 photos of the period by Franz Roh and Jan Tschichold, with German, French and English text, 18pp. of introductory text and 76 photographs and photographic experiments (one per page with captions for each) with a final page of photographers addresses at the back. Franz Roh introduction: “Mechanism and Expression: The Essence and Value of Photography”. Cover and interior pages designed by Jan Tschichold, Munich featuring El Lissitzky’s 1924 self-portrait, “The Constructor” on the cover. One of the most important and influential publications about modern photography and the New Vision published to accompany Stuttgart’s 1929 Film und Foto exhibition with examples by but not limited to: Eugene Atget, Andreas Feininger, Florence Henri, Lissitzky, Max Burchartz, Max Ernst, George Grosz and John Heartfield, Hans Finsler, Tschichold, Vordemberge Gildewart, Man Ray, Herbert Bayer, Edward and Brett Weston, Piet Zwart, Moholy-Nagy, Renger-Patzsch, Franz Roh, Paul Schuitema, Umbo and many others. A very good Japanese- bound softcover with soiling to the white pictorial wrappers and light wear near the margins. Spine head/heel chipped with paper loss and small tears and splits. Interior pages bright and binding tight. (#KC15855) $750.00 1 Toyen. Paris, 1953. May 1953, Galerie A L’ Etoile Scellee, 11, 3 Rue du Pre aux Clercs, Paris 1953. Ephemera, folded approx. -

Hermès Supports Preservation of the Glass House with Elaine Lustig Cohen’S "Centered Rhyme" Silk Twill Scarf

Hermès Supports Preservation of The Glass House with Elaine Lustig Cohen’s "Centered Rhyme" Silk Twill Scarf February, 2017 – Hermès of Paris, Inc. is honored to introduce Centered Rhyme, a limited‐edition 90x90cm silk twill scarf featuring a design by the late American artist Elaine Lustig Cohen (1927–2016). The design is based on a large‐scale 1967 painting by the artist. Elaine Lustig Cohen was highly regarded as a graphic designer, artist, and rare book dealer throughout her career, which spanned over fifty years. In 1955, she began her design work in New York by extending the idiom of European modernism into an American context for her diverse clientele of publishers, corporations, cultural institutions, and architects. Her first client was the renowned architect Philip Johnson (1906‐2005) – creator of the celebrated Glass House (1949) in New Canaan, Connecticut – who commissioned her to design the lettering and signage for the iconic Seagram Building. The two forged an important bond that resulted in a variety of projects for the Glass House, Yale University, and Lincoln Center, among others. As a painter, Lustig Cohen developed a hard‐edged style in the 1960s and 1970s that asserted the canvas’ flat surface. She continued to experiment with bold colors, linear patterning, and abstract shapes in a variety of media including collage and three‐dimensional objects Following a 2015 exhibition of the artist's early paintings and graphic design at The Glass House, Pierre‐ Alexis Dumas, artistic director of Hermès, met the artist at her Manhattan home and conceived of a scarf based on one of her paintings; Centered Rhyme (1967). -

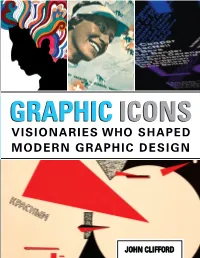

Visionaries Who Shaped Modern Graphic Design

Who are history’s most influential graphic designers? In this fun, fast-paced introduction to the most iconic designers of our time, author ICONS GRAPHIC John Clifford takes you on a visual history tour that’s packed with the posters, ads, logos, typefaces, covers, and multimedia work that have made these designers great. You’ll find examples of landmark work by such industry luminaries asE l Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko, A.M. Cassandre, Alvin Lustig, Cipe Pineles, Paul Rand, Saul Bass, Milton Glaser, Wim Crouwel, Stefan Sagmeister, John Maeda, Paula Scher, and more. “ Packed with inspiration and information about the pioneers and radicals and experimenters who broke the rules of design.” — Stephen Doyle, Creative Director, Doyle Partners MODERN GRAPHIC VISIONARIES WHO GRAPHICGRAPHIC ICONSICONS S D VISIONARIES WHO SHAPED HAPED HAPED ESI G N MODERN GRAPHIC DESIGN JOHN CLIFFORD Who coined the term graphic design? Who turned film titles into an art? Who pioneered infor- mation design? Who was the first female art director of a mass-market American magazine? In Graphic Icons: Visionaries Who Shaped Modern Graphic Design, you start with the who and quickly learn the what, when, and why behind graphic design’s most important breakthroughs and the impact their creators had, and continue to have, on the world we live in. John Clifford is an award-winning creative director and principle Your favorite designer didn’t at Think Studio, a New York City design firm with clients that make the list? Join the conversation include The World Financial Center, L.L.Bean, Paul Labrecque, at graphiciconsbook.com The Monacelli Press, and Yale School of Architecture. -

For Immediate Release Elaine Lustig Cohen June 13

Centered Rhyme, 1967. Acrylic on canvas. 60 x 60 inches. Map of New Canaan, Connecticut, 1962. Signage for Brasserie, 375 Park Avenue, 1957. Courtesy of the artist and P!, New York Courtesy of the artist and P!, New York Courtesy of the artist and P!, New York For Immediate Release Elaine Lustig Cohen June 13 - September 28, 2015 The Glass House presents the first survey to explore the relationship between the early paintings and pioneering design projects of Elaine Lustig Cohen. Based in New York, Lustig Cohen has been highly regarded as a graphic designer, artist, and rare book dealer throughout her career, which spans over fifty years. On view in the Painting Gallery, the exhibition includes a selection of her paintings from the 1960s and 1970s as well as examples of her multiyear collaboration with architect Philip Johnson, among other projects. In 1955, Lustig Cohen began a graphic design practice that integrated the aesthetics of European modernism within a distinctly American visual idiom for her diverse clientele of publishers, corporations, cultural institutions, and architects. Her first client was Johnson, who commissioned her to work on the lettering and signage for the Seagram Building. The two forged an important bond that resulted in a variety of projects for the Glass House, Yale University, Lincoln Center, the Munson- Williams-Proctor Art Institute, and the Sheldon Museum of Art, among others, as well as commissions from Johnson’s clients, including John de Menil and the Schlumberger oil company. As a painter, Lustig Cohen developed a hard-edged style in the 1960s and 1970s that engaged the physicality of the canvas’ flat surface. -

Good Design Catalog 2012.Pdf

aalto albers bayer beall bel geddes bertoia breuer brodovitch burtin carboni deskey eames modernism 101 entenza frankl rare design books frey giedion girard gropius hitchcock kepes lászló loewy lustig lustig-cohen matter mies van der rohe moholy-nagy nelson catalog neutra ponti 2012 rand rietveld rudolph saarinen schindler shulman sutnar vignelli weber wormley wright zwart INTRODUCTION In THE LANGUAGE OF THINGS, Deyan Sudjic identified design as “the DNA” of a society, “the code that we need to explore if we are to stand a chance of understanding the nature of the modern world.” With this spirit of exploration and understanding, we offer our perspec- tive on the origins and influences of theGood Design movement. Anti- quarian book catalogs, like the collections of their readers, usually strive for a tentative coherence: books by a single author, books by two authors, books by women, cookbooks, etc. There are as many catego- ries as there are collectors, and nearly as many specialized catalogs intended to abet them. The great writer and bibliophile Walter Benjamin expressed a wish to compose an original work entirely of quotations. He also considered the arrangement of the books in his library to be one of his most de- manding literary creations. Benjamin asserted the choice and ar- rangement of the books told a story and promoted a theory of knowl- edge. And while he never revealed the secrets, he assumed it was possible for some other critic to read the story, to decode the mean- ing, and to compose philosophical commentaries about it. Our catalog cannot claim this kind of coherence, if for no other reason than the arbitrary demands of an alphabetical arrangement necessarily distorts it. -

Graphic D E S I G N 2 0 1 7 C a T a L

modernism101.com rare design books GRAPHIC DESIGN 2017 CATALOG THE MAIL SLOT FOR THE BROWNSTONE ON EAST 70TH STREET featured a sign that simply stated: No Menus. The typography was simple, direct and elegant—and signaled I was indeed at the right address. I nervously adjusted the knot on my tie, squared my blazer, and looked down at the new shoes pinching my toes. My wife had cajoled me into purchasing a wardrobe for this moment. Back then I was used to operating in the shadows and cared little about my appearance. This was different. Molly insisted I look sharp. I rang the buzzer and during the next few seconds reflected on all the roads traveled and all the choices made that funneled me from the hard- scrabble oilfields of West Texas to this sidewalk on the Upper East Side. The heavy door clicked open. It was time to meet Elaine Lustig Cohen. Elaine had introduced herself via email a couple of years before when she contacted me needing some material for the Alvin Lustig monograph she was writing with Steven Heller. She always ended her correspondence with an invitation to visit the next time I was in New York City. I looked forward to her emails and her interest in my affairs made me proud. I was doing something right if the co-founder of Ex-Libris gave her approval. “Come on up Randall,” a disembodied voice invited me from the stairwell to the left. I climbed up into the type of clean, well-lighted space that had only previously existed in my imagination.