Who Gaind When Workers Train?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CGHE Keynote Lorraine Dearden Final

Creating Competition and Efficiency in English Higher Education: Economic myths and realities Lorraine Dearden Department of Social Science, UCL Institute of Education and Institute for Fiscal Studies Outline • Quick tour of the Economics of Higher Education • Outline recent reforms in UK that have been driven by increasing competition • 2012 Fee reform (fee competition) • 2016 reforms allowing private providers to provide university courses and get access to government subsidised student loans • What does economics and international experience tell us about the likely outcomes of these reforms aimed at increasing competition? Why might the market alone lead to inefficient outcomes in HE provision? 1. Credit market failure 2. Externalities 3. Risk and uncertainty 4. Information problems 1. Credit market failure • HE study by students requires cash for fees and living expenses • With perfect credit markets, students borrow now and repay from future income • But credit markets are not perfect: 1. Lack of collateral to secure debt against 2. Asymmetric information: borrower has more information than lender 3. Adverse selection/moral hazard problems high interest/rates and/or credit rationing 2. Externalities • Education may create benefits to society over and above those that accrue to the individual • Total return to education = private return + social return • Individuals do not generally incorporate social return to education in weighing up costs and benefits? 3. Risk and uncertainty • Student may be reluctant to borrow • Perceived risk of failing the degree • Uncertain returns to a degree: positive on average but high variance • Might need high risk premium to make the investment worthwhile • Debt aversion • Understanding behavioural responses crucial 4. -

The US College Loans System Lessons from Australia and England

Economics of Education Review xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Economics of Education Review journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/econedurev The US college loans system: Lessons from Australia and England ⁎ Nicholas Barra, Bruce Chapmanb, Lorraine Deardenc, , Susan Dynarskid a London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom b Australian National University, Australia c University College London, Institute for Fiscal Studies and IZA, United Kingdom d University of Michigan and NBER, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT JEL classification: There is wide agreement that the US student loan system faces significant problems. Seven million borrowers are H28 in default and many more are not repaying for reasons such as returning to school, or economic hardship. The I22 stress of repayments faced by many students results at least in part from the design of US student loans. I28 Specifically, loans are organised like a mortgage, with fixed monthly repayments over a fixed periodoftime, J24 creating a high repayment burden on borrowers with low income. This paper draws on the experience of the Keywords: income-contingent loan (ICL) systems operating in England and Australia, in which monthly or two-weekly Income-contingent loans repayments are related to the borrower's income in that period, thus building in automatic insurance against Mortgage-type loans inability to repay during periods of low income. We discuss the design of this type of loan in detail since such an Student loan design exercise seems to be largely absent in the US literature. Drawing on data from the US Current Population Survey Loan defaults (CPS) we provide two main empirical contributions: a stylised illustration of the revenue and distributional implications of different hypothetical ICL arrangements for the USA; and an illustration of repayment problems faced by low-earning borrowers in the US loan system, including a plausible example of adverse outcomes with respect to Stafford loans. -

When You Are Born Matters: Evidence for England

When you are born matters: evidence for England IFS Report R80 Claire Crawford Lorraine Dearden Ellen Greaves When You Are Born Matters: Evidence for England Claire Crawford Institute for Fiscal Studies Lorraine Dearden Institute for Fiscal Studies; Institute of Education, University of London Ellen Greaves Institute for Fiscal Studies Copy-edited by Judith Payne Institute for Fiscal Studies 7 Ridgmount Street London WC1E 7AE Published by The Institute for Fiscal Studies 7 Ridgmount Street London WC1E 7AE Tel: +44 (0) 20-7291 4800 Fax: +44 (0) 20-7323 4780 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.ifs.org.uk © The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2013 ISBN 978-1-909463-08-0 Preface The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the Nuffield Foundation (grant number EDU/36559), which was the main funder of this project and has provided generous support for this programme of work. The Nuffield Foundation is an endowed charitable trust that aims to improve social well-being in the widest sense. It funds research and innovation in education and social policy and also works to build capacity in education, science and social science research. The Nuffield Foundation has funded this project, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Foundation. More information is available at http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org. The Esmée Fairbairn Foundation (grant number ED/05-0251), the Department for Children, Schools and Families (now the Department for Education) via the Centre for the Economics of Education, and the Economic and Social Research Council via the Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (grant number RES-544-28-0001) and grant number RES-060-23-0011 provided support for earlier work featured in this report. -

Longitudinal and Life Course Studies

Longitudinal and Life Course Studies: ISSN 1757-9597 Supplement: CELSE2010 Abstracts Longitudinal and Life Course Studies: International Journal Supplement: CELSE2010 Abstracts International Journal VOLUME 1 VOLUME | ISSUE 3 | Published by 2010 Company No. 5496119 Reg Charity No 1114094 www.longviewuk.com VOLUME 1 | ISSUE 3 | 2010 Longitudinal and Life Course Studies: International Journal Supplement: CELSE2010 Abstracts Guest Editors Abstract Review Committee Demetris Pillas Bianca De Stavola Chryssa Bakoula Nancy Pedersen ESRC International Centre for Life Course Studies in London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of Athens, Greece Karolinska Institutet, Sweden Society and Health, UK UK David Blane Demetris Pillas Alina Rodriguez David Blane ESRC International Centre for Life Course Studies in ESRC International Centre for Life Course Studies in Uppsala University, Sweden ESRC International Centre for Life Course Studies in Society and Health, UK Society and Health, UK Kyriacos Pillas Society and Health, UK Eric Brunner George Ploubidis Cyprus Pedagogical Institute, Cyprus George Ploubidis University College London, UK London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Marjo-Riitta Jarvelin London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Leda Chatzi UK Imperial College London, UK UK University of Crete, Greece Theodora Pouliou Bianca De Stavola UCL Institute of Child Health, UK London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Chris Power Longitudinal and Life Course Studies: Members UK UCL Institute of Child Health, UK -

The US College Loans System: Lessons from Australia and England

Nicholas Barr, Bruce Chapman, Lorraine Dearden and Susan Dynarski The US college loans system: lessons from Australia and England Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Barr, Nicholas and Chapman, Bruce and Dearden, Lorraine and Dynarski, Susan (2018) The US college loans system: lessons from Australia and England. Economics of Education Review. ISSN 0272-7757 (In Press) DOI: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.07.007 © 2018 Elsevier Ltd. This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/89405/ Available in LSE Research Online: July 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. The US College Loans System: Lessons from Australia and England1 Nicholas Barr, London School of Economics and Political Science Bruce Chapman, Australian National University Lorraine Dearden, University College London, Institute for Fiscal Studies and IZA Susan Dynarski, University of Michigan and NBER Abstract There is wide agreement that the US student loan system faces significant problems. -

The Impact of Undergraduate Degrees on Early-Career Earnings Research Report November 2018

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Education Resource Archive The impact of undergraduate degrees on early-career earnings Research report November 2018 Chris Belfield, Jack Britton, Franz Buscha, Lorraine Dearden, Matt Dickson, Laura van der Erve, Luke Sibieta, Anna Vignoles, Ian Walker and Yu Zhu Institute for Fiscal Studies Contents Executive Summary 5 1 Introduction 7 2 Data 10 2.1 Sample selection . 10 2.2 Data descriptives . 14 2.3 Subgroup analysis . 22 3 Methodology 28 3.1 Inverse Probability Weighting First Stage . 33 3.2 Model of earnings . 34 4 Overall results 35 4.1 Average overall returns . 35 4.2 Heterogeneity in overall returns by background characteristics . 39 5 Subject results 41 5.1 Overall returns by subject . 41 5.2 Heterogeneity in subject returns . 44 6 HEI results 48 6.1 Overall returns by HEI . 48 6.2 Heterogeneity in HEI returns . 53 7 Course results 57 8 Returns at different ages 62 9 Conclusion 65 1 List of Figures 1 Real earnings by education level . 15 2 Real earnings by education level . 16 3 Probability of being in sustained employment by education level . 16 4 Real earnings by SES . 17 5 Real earnings by maths GCSE grade . 18 6 Real earnings by English GCSE grade . 18 7 Real earnings by degree subject at age 29, men . 19 8 Real earnings by degree subject at age 29, women . 20 9 Real earnings by HEI at age 29, men . 21 10 Real earnings by HEI at age 29, women . -

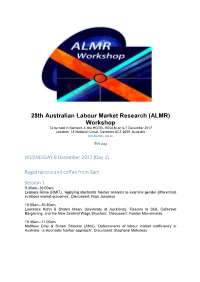

(ALMR) Workshop to Be Held in Ballroom 4, the HOTEL REALM on 6-7 December 2017 Location: 18 National Circuit, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia Hotelrealm.Com.Au

28th Australian Labour Market Research (ALMR) Workshop To be held in Ballroom 4, the HOTEL REALM on 6-7 December 2017 Location: 18 National Circuit, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia hotelrealm.com.au See map WEDNESDAY 6 December 2017 (Day 1) Registrations and coffee from 9am Session 1 9.30am–10.00am Leonora Risse (RMIT), ‘Applying stochastic frontier analysis to examine gender differentials in labour market outcomes’. Discussant: Raja Junankar 10.00am–10.30am Lawrence Kahn & Sholeh Maani (University of Auckland), ‘Returns to Skill, Collective Bargaining, and the New Zealand Wage Structure’. Discussant: Kostas Mavromaras 10.30am–11.00am Matthew Gray & Sriram Shankar (ANU), ‘Determinants of labour market inefficiency in Australia - a stochastic frontier approach’. Discussant: Stephane Mahuteau Morning Tea 11.00am–11.30am Session 2 11.30am–12.00noon Danielle Venn (ANU), ‘Poverty transitions in non-remote Indigenous households: The role of labour market and household dynamics’. Discussant: Anne Daly 12.00noon–12.30pm Bob Breunig, Syed Hasan & Boyd Hunter (ANU), ‘Financial stress of Indigenous Australians: Evidence from NATSISS 2014-15 data’. Discussant: Alison Preston 12.30pm–1.00pm Elish Kelly (Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin). ‘Atypical Work and Ireland’s Labour Market Collapse and Recovery’. Discussant: Boyd Hunter Lunch 1.00pm–2.00pm 1.40pm Lorraine Dearden (Institute for Fiscal Studies and University College London) UK administrative data and it impact on labour economics (for those who finish lunch early) Session 3 2.00pm–2.30pm Riyana Miranti & Jinjing Li (University of Canberra), ‘Working Hours Mismatch, Job Strain and Mental Health among Mature-Age Workers in Australia’. Discussant: Elish Kelly 2.30pm–3.00pm Greg Connolly & Carl Francia (Department of Employment), ‘The Relationship between Labour Underutilisation Rates and the Proportion of Unemployment Allowees’. -

The Impact of Undergraduate Degrees on Lifetime Earnings: Online Appendix

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Britton, Jack; Dearden, Lorraine; van der Erve, Laura; Waltmann, Ben Research Report The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earnings IFS Report, No. R167 Provided in Cooperation with: Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), London Suggested Citation: Britton, Jack; Dearden, Lorraine; van der Erve, Laura; Waltmann, Ben (2020) : The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earnings, IFS Report, No. R167, Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), London, http://dx.doi.org/10.1920/re.ifs.2020.0167 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/235056 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu The Impact of Undergraduate Degrees on Lifetime Earnings: Online Appendix Jack Britton, Lorraine Dearden, Laura van der Erve and Ben Waltmann February 2020 A Sample Selection and Data Quality A.1 HESA Data The HESA data set presents a number of challenges. -

The Impact of Undergraduate Degrees on Lifetime Earnings Online Appendix February 2020

The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earnings Online appendix February 2020 Jack Britton, Lorraine Dearden, Laura van der Erve and Ben Waltmann Institute for Fiscal Studies The Impact of Undergraduate Degrees on Lifetime Earnings: Online Appendix Jack Britton, Lorraine Dearden, Laura van der Erve and Ben Waltmann February 2020 A Sample Selection and Data Quality A.1 HESA Data The HESA data set presents a number of challenges. One is lower data quality in the early years of the data: crucial information is sometimes missing or inconsistent across years. As far as charac teristics ought to be constant across years, we have dealt with missing data by taking the earliest record as authoritative.1 In cases where information on subject studied was missing, we have filled in missing data from earlier years on the same course of study.2 We also harmonised the birth year of each individual, taking data from undergraduate degrees as the most authoritative for cohorts for which no NPD data are available.3 A second challenge is changing variable definitions over time. The most important example of this for our purposes is a radical change in the way HESA classifies courses that occurred between the 2006/07 and 2007/08 academic years.4 As far as possible, we have attempted to follow HESA’s own coarser classification of degrees that includes a category for first degrees.5 However, we have diverged slightly from this classification in the interest of continuity with the pre-2007/08 classification scheme. As a result, we classify the following course codes as ‘undergraduate degrees’ for our pur poses: • the courseaim codes 18 to 24 • the qualaim codes H00, H11, H12, H16, H18, H22, H23, H24, H50, I00, I11, I16. -

The Impact of Undergraduate Degrees on Lifetime Earnings

The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earnings Jack Britton, Lorraine Dearden, Laura van der Erve and Ben Waltmann Contents Executive Summary 6 1 Introduction 10 2 Data 11 2.1 Data linkage .......................................... 11 2.2 Student numbers in the HESA data ............................. 13 2.3 Mid-career earnings ...................................... 16 2.4 Labour Force Survey ..................................... 18 2.5 Fully-linked LEO analysis sample .............................. 19 3 Methodology 20 3.1 Modelling earnings: graduates aged 31–40 ........................ 22 3.1.1 Modelling employment/worklessness . 24 3.1.2 Modelling rank dependence conditional on employment . 25 3.1.3 Assigning earnings to ranks ............................. 27 3.2 Modelling earnings using LFS survey data ........................ 28 3.2.1 Modelling employment ............................... 28 3.2.2 Modelling rank dependence conditional on employment . 29 3.2.3 Assigning earnings to ranks ............................. 29 3.2.4 Modelling retirement ................................. 30 3.3 Estimation ........................................... 30 3.3.1 Returns at each age .................................. 30 3.3.2 Lifetime returns .................................... 31 4 Simulated earnings over the life cycle 33 4.1 Earnings and worklessness by age ............................. 33 4.2 Net lifetime earnings ..................................... 37 5 Returns at different ages 42 5.1 Overall returns by age ................................... -

The Dynamics of Low Pay and Unemployment in Early 1990S Britain

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Gosling, Amanda; Johnson, Paul; McCrae, Julian; Paull, Gillian Research Report The dynamics of low pay and unemployment in early 1990s Britain IFS Report, No. R54 Provided in Cooperation with: Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), London Suggested Citation: Gosling, Amanda; Johnson, Paul; McCrae, Julian; Paull, Gillian (1997) : The dynamics of low pay and unemployment in early 1990s Britain, IFS Report, No. R54, ISBN 978-1-87335-772-9, Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), London, http://dx.doi.org/10.1920/re.ifs.1997.0054 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/64582 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu The Dynamics of Low Pay and Unemployment in Early 1990s Britain Amanda Gosling Paul Johnson Julian McCrae Gillian Paull The Institute for Fiscal Studies 7 Ridgmount Street London WClE 7AE Published by The Institute for Fiscal Studies 7 Ridgmount Street London WC IE 7 AE tel. -

RICHARD BLUNDELL CBE FBA Curriculum Vitae (March 2018)

PROFESSOR SIR RICHARD BLUNDELL CBE FBA Curriculum Vitae (March 2018) Ricardo Professor of Political Economy Director Department of Economics ESRC Centre for the Micro-Economic Analysis of University College London Public Policy (CPP@IFS) Gower Street Institute for Fiscal Studies London WC1E 6BT, UK 7 Ridgmout Street e-mail: [email protected] London WC1E 7AE Tel: +44 (0)207679 5863 Tel: +44 (0)20 7291 4820 Mobile: +44 (0)7795334639 Fax: +44 (0)20 7323 4780 Website: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~uctp39a/ Date of Birth: 1 May 1952 Education and Employment: 1970 - 1973 B.Sc. University of Bristol. (Economics with Statistics, First Class). 1973 - 1975 M.Sc. London School of Economics (Econometrics). 1975-1984 Lecturer in Econometrics, University of Manchester. 1984- Ricardo Chair of Political Economy, University College London, (1988-1992 Dept. Chair). 1986 - 2016 Research Director, Institute for Fiscal Studies. 1991- Director: ESRC Centre for the Micro-Economic Analysis of Public Policy, IFS. 2017- Associate Faculty Member, TSE, Toulouse 1999- IZA Research Fellow 2006- CEPR Research Fellow 1980 Visiting Professor, University of British Columbia. 1993 Visiting Professor, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1994 Ford Visiting Professor, University of California at Berkeley. 1999 Visiting Professor, University of California at Berkeley. Honorary Doctorates Doktors der Wirtschaftswissenschaften ehrenhalber, University of St Gallen, St Gallen, Switzerland 2003 Æresdoktorar, NHH, Norwegian School of Economics, Bergen, Norway 2011 Ehrendoktorwürde Ökonomen, University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany 2011 Dottorato honoris causa in Scienze economiche, Università della Svizzera italiana, Switzerland 2016 Doctor of Laws honoris causa, University of Bristol, Bristol, 2017 Doctorato Honoris Causa in Economics, University of Venice, Ca’Foscari, Italy, 2018 Presidency of Professional Organizations 2004 President, European Economics Association.