Mining and Communities in Northern Canada : History, Politics, and Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henk Huijbers Fonds, 98/30 (Yukon Archives Caption List)

Henk Huijbers fonds acc# 98/30 YUKON ARCHIVES PHOTO CAPTION LIST Caption information supplied by donor. Information in square brackets [ ] provided by Archivist. #1, #2, #31-49 were all loose items. #3- 30 were from albums. Further details about these photographs are available in the Yukon Archives Descriptive Database at www.yukonarchives.ca PHO 097 YA# Description: 98/30 #1 Father Huijbers with Red Cross Ambulance 1940, Dunkirk. We had to move quite a lot of wounded. 98/30 #2 Three identity photos. Goodbye photos for when I was going to the Yukon. 98/30 #3 Lower Post and Watson Lake. Washing clothes with washboard and melted snow 1947. 98/30 #4 The daily work that you have to do is to cut the wood for yourself 98/30 #5 Lower Post, walking with snowshoes. Northern trench [same as #19] 98/30 #6 Father Huijbers with gun. Little partridge, grouse. Big snowshoes in the spring. 98/30 #7 First boat coming to Mayo - the Keno - June 8, 1948. The Yukon River makes a big turn in Mayo. Every dog was calling the boat. The whole town was there. 98/30 #8 Mine at Mayo; Mount Lookout 1948 98/30 #9 South of Lower Post 98/30 #10 Coal River south of Lower Post 98/30 #11 Alaska Highway south of Coal River 98/30 #12 Alaska Highway - same day 98/30 #13 Coal River view - hot springs south of Lower Post 98/30 #14 [Bridge over river] 98/30 #15 Devil’s Trail, south of Lower Post 98/30 #16 A. -

CHON-FM Whitehorse and Its Transmitters – Licence Renewal

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2015-278 PDF version Reference: 2015-153 Ottawa, 23 June 2015 Northern Native Broadcasting, Yukon Whitehorse, Yukon and various locations in British Columbia, Northwest Territories and Yukon Application 2014-0868-3, received 29 August 2014 CHON-FM Whitehorse and its transmitters – Licence renewal The Commission renews the broadcasting licence for the Type B Native radio station CHON-FM Whitehorse and its transmitters from 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2021. This shortened licence term will allow for an earlier review of the licensee’s compliance with the regulatory requirements. Introduction 1. Northern Native Broadcasting, Yukon filed an application to renew the broadcasting licence for the Type B Native radio station CHON-FM Whitehorse and its transmitters CHCK-FM Carmacks, CHHJ-FM Haines Junction, CHOL-FM Old Crow, CHON-FM-2 Takhini River Subdivision, CHON-FM-3 Johnson’s Crossing, CHPE-FM Pelly Crossing, CHTE-FM Teslin, VF2024 Klukshu, VF2027 Watson Lake, VF2028 Mayo, VF2035 Ross River, VF2038 Upper Liard, VF2039 Carcross, VF2049 Dawson City, VF2125 Takhini River Subdivision, VF2126 Keno City, VF2127 Stewart Crossing, VF2128 Tagish, VF2147 Destruction Bay, VF2148 Whitehorse (Mayo Road Subdivision), VF2311 Lower Post and VF2414 Faro, Yukon; VF2306 Atlin and VF2353 Good Hope Lake, British Columbia; VF2354 Aklavik, and VF2498 Tsiigehtchic (Arctic Red River), Northwest Territories, which expires on 31 August 2015. The Commission did not receive any interventions regarding this application. Non-compliance 2. Section 9(2) of the Radio Regulations, 1986 (the Regulations) requires licensees to file an annual return by 30 November of each year for the broadcast year ending the previous 31 August. -

Recreation Therapy in Yukon 2

Recreation Therapy in the Yukon: Larger than Life G illian Kirk, BSC REC, CTRS SESSION OBJECTIVES Identify 3 barriers and challenges to leisure in the Yukon/Northern settings. Identify 2 strategies to successfully work in a new cultural context. Identify 3 strategies being used to advance Recreation Therapy in the Yukon. www.yourwebsite.com WHAT IS CULTURE? Culture can be conceptualized as part of an individual’s unique identity, comprising ideological, personal, cultural, contextual, and universal factors. (Collins & Arthur, 2010a) CULTURAL COMPETENCE FRAMEWORK Develop knowledge, attitudes, and skills across 3 domains: (a)cultural self-awareness (b)awareness of the cultural identities of clients or understanding the worldview of clients (c) culturally sensitive working alliances (Collins & Arthur, 2010a) GETTING TO KNOW THE YUKON THE EXPANSE OF THE YUKON In the Yukon: Area: 483,450 km² (that’s about the size of Spain) Population: 38,630 In the city of Whitehorse: Area: 416.54km2 Population: 29,962 In the city of Dawson: Area: 32.45 km² Population: 2,220 (Yukon Bureau of Statistics, 2017) Beaufort Sea Herschel Island r e i v R Traditional Territories h Inuvialuit t i r F Settlement r e v i Region R of Yukon First Nations w o l DIVERSITY B and Settlement Areas ! µ Inuvik of Inuvialuit and Tetlit Gwich'in YUKON TERRITORY August 2013 Old Crow r ! p i n e e r c u P o v i STATISTICS R Tetlit Gwich'in B e l l Secondary Use 0 50 100 200 km ! Vuntut Fort McPherson R i v e Gwitchin r Administrative centres of First Nations are depicted in the colour of their Traditional Territory. -

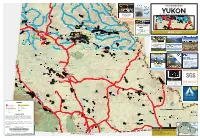

MAP-Yukon(Ns)

Dempster (V) Fishing Branch Ecological Reserve Eagle River Peel River Porcupine River Fishing Branch Wilderness Preserve East Porcupine River Nor (Cu, Au, U) Caribou River Fishing Branch Habitat Protection Area Dempster Highway Porcupine N River Snake 0 50 100 River Blackstone River kilometers River YUKON Hart River ALASKA Ogilivie r Dempster (V) Fishing Branch Eagle Rive River Ecological Reserve Peel River Porcupine River Wind Fishing Branch Wilderness Preserve Ogilivie River Bonnet East P orcupine R Nor (Cu, Au, U) Caribou River Fishing Branch Habitat Protection Area iv er Plume River Dempster Highway INDEX Porcupine N Blackstone River River of Snake MAP AREA 0 50 100 River TSX VGCX | VGCX.COM Blackstone River kilometers River YUKON Hart River ALASKA Ogilivie River Hart River Wind Ogilivie River Bonnet P Plume River INDEX Blackstone River of a MAP AREA Igor (Yup) (Cu, Au, Fe, U) High-Grade Copper-Gold in Yukon, c i Hart River f Canada’s Prolifi c Minto Copper Belt P i a Igor (Yup) (Cu, Au, Fe, U) c i c f i c Olympic-Rob Project (Cu, U) Wind River O c c e e i e t n a n a Eagle n a l Litt e l STRATEGIC O Olympic-Rob Project (Cu, U) t c River Highway Wind River A O c Monster (Co, Cu, Au, Ag) c i STRATEGIC e t STRATEGIC n Dempster Wind River Wernecke Breccia (Cu, Au, Ag, U) a Hart River n a Tombstone Natural Eagle n a Little Little Environment Park e STRATEGIC TSX.V: GCX l STRATEGIC t c LEGEND Highway River gcxcopper.com OTCQB: GCXXF A O Clinton Creek Operating Mines Mines in Construction METALLIC MINERALS Bonnet Plume River North NW Shell -

Yukon & the Dempster Highway Road Trip

YUKON & THE DEMPSTER HIGHWAY ROAD TRIP Yukon & the Dempster Highway Road Trip Yukon & Alaska Road Trip 15 Days / 14 Nights Whitehorse to Whitehorse Priced at USD $1,642 per person INTRODUCTION The Dempster Highway road trip is one of the most spectacular self drives on earth, and yet, many people have never heard of it. It’s the only road in Canada that takes you across the Arctic Circle, entering the land of the midnight sun where the sky stays bright for 24 hours a day. Explore subarctic wilderness at Tombstone National Park, witness wildlife at the Yukon Wildlife Preserve, see the world's largest non-polar icefields and discover the "Dog Mushing Capital of Alaska." In Inuvik, we recommend the sightseeing flight to see the Arctic Ocean from above. Itinerary at a Glance DAY 1 Whitehorse | Arrival DAY 2 Whitehorse | Yukon Wildlife Preserve DAY 3 Whitehorse to Hains Junction | 154 km/96 mi DAY 4 Kluane National Park | 250 km/155 mi DAY 5 Haines Junction to Tok | 467 km/290 mi DAY 6 Tok to Dawson City | 297 km/185 mi DAYS 7 Dawson City | Exploring DAY 8 Dawson City to Eagle Plains | 408 km/254 mi DAY 9 Eagle Plains to Inuvik | 366 km/227 mi DAY 10 Inuvik | Exploring DAY 11 Inuvik to Eagle Plains | 366 km/227 mi DAY 12 Eagle Plains to Dawson City | 408 km/254 mi Start planning your vacation in Canada by contacting our Canada specialists Call 1 800 217 0973 Monday - Friday 8am - 5pm Saturday 8.30am - 4pm Sunday 9am - 5:30pm (Pacific Standard Time) Email [email protected] Web canadabydesign.com Suite 1200, 675 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC, V6B 1N2, Canada 2021/06/14 Page 1 of 5 YUKON & THE DEMPSTER HIGHWAY ROAD TRIP DAY 13 Dawson City to Mayo | 230 km/143 mi DAY 14 Mayo to Whitehorse | 406 km/252 mi DAY 15 Whitehorse | Departure MAP DETAILED ITINERARY Day 1 Whitehorse | Arrival Welcome to the “Land of the Midnight Sun”. -

Y U K O N Electoral District Boundaries Commission

Y U K O N ELECTORAL DISTRICT BOUNDARIES COMMISSION INTERIM REPORT NOVEMBER 2017 Yukon Electoral District Commission de délimitation des Boundaries Commission circonscriptions électorales du Yukon November 17, 2017 Honourable Nils Clarke Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Yukon Legislative Assembly Whitehorse, Yukon Dear Mr. Speaker: We are pleased to submit the interim report of the Electoral District Boundaries Commission. The report sets out the proposals for the boundaries, number, and names of electoral districts in Yukon, and includes our reasons for the proposals. Proposals are based on all considerations prescribed by the Elections Act (the Act). Our interim report is submitted in accordance with section 415 of the Act for tabling in the Legislative Assembly. Our final report will be submitted by April 20, 2018 in accordance with section 417 of the Act. The final report will consider input received at upcoming public hearings and additional written submissions received by the Electoral District Boundaries Commission. Sincerely, The Honourable Mr. Justice R.S. Veale Commission Chair Darren Parsons Jonas Smith Anne Tayler Lori McKee Member Member Member Member/ Chief Electoral Officer Box ● C.P. 2703 (A-9) Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6 Phone● téléphone (867) 456-6730 ● 1-855-967-8588 toll free/sans frais Fax ● Télécopier (867) 393-6977 e-mail ● courriel [email protected] website ● site web www.yukonboundaries.ca www.facebook.com/yukonboundaries @yukonboundaries Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. -

MEDIA KIT Published By: YUKON NEWS DISTRIBUTION

Yukon News MEDIA KIT Published by: YUKON NEWS DISTRIBUTION Total Circulation As of May 2019. WEDNESDAY ➤ 4250 | FRIDAY ➤ 5575 Our Circulation numbers are proudly audited quarterly by Alliance for Audited Media. Your Community Connection: Serving the Yukon since 1960. The Yukon News is the only newspaper that is regularly circulated in every Yukon community. Advertising in the Yukon News gives you the best value for your money. Tuktoyaktuk Inuvik CONTACT FOR FLYER INSERTIONS: Aklavik Stephanie Newsome OLD CROW T. 867-667-6258 (Ext. 230) Ft. McPherson Arctic Red River E. [email protected] Eagle Plains Eagle Jack Wade COMMUNITIES SERVED Chicken Boundary ELSA BY THE YUKON NEWS DAWSON Keno City Tok Tetlin Jct. MAYO Tetlin Stewart Crossing Northway Junction PELLY CROSSING BEAVER CREEK Fort Selkirk Minto FARO Little Salmon CARMACKS ROSS RIVER BURWASH LANDING Destruction Bay Champagne Mount Logan HAINES WHITEHORSE JUNCTION Johnson’s Crossing Klukshu Upper Jakes WATSON LAKE CARCROSS Tagish Corner TESLIN Liard Bennett Lower Post Log Cabin Fraser ATLIN, BC Klukwan Skagway Cassiar Haines Port Ft. Chilkoot Nelson CONTACT US: 1-867-667-6285 2 Yukon News STEPHANIE SIMPSON (Ext. 208): [email protected] RATES & SERVICES National Advertising and Ad Agency Placements Call an Advertising Representative for more information. Market Rates *Excludes Territorial and Federal Governments, Municipalities, First Nation Governments, Crown Corporations, and government Boards and Committees Colour Ads We offer full colour printing on all ad sizes. Columns Our paper is built in the 6-column format. ABOUT US Year after year, the Yukon News wins awards regionally (British Columbia) and nationally for its excellence in journalism, photography, editorial cartoons and graphic art. -

Population As of 2019 There Were 41,352 People Living in Yukon

1 Population As of 2019 there were 41,352 people living in Yukon. Of those, 32,304 were living in the capital city of Whitehorse. Capital City Whitehorse is the major northern hub of Yukon surrounded by wilderness with the amenities of a city paired with the demeanor of a close-knit community. Size: 482,443 square kilometer Location Yukon is one of three territories in Canada’s north. It sits with Alaska to the west and the Northwest Territories to the east. The Arctic Circle runs through the Yukon and the territory has 430 kilometers of shoreline along the Beaufort Sea. Name ‘The Land of the Midnight Sun’ is a name given to Yukon in the summer time when there is almost 24 hours of daylight due to the territory’s latitude. The name ‘Yukon’ comes from the native word ‘Yuk-un-ah’ which means, ‘Great River’ in reference to the Yukon River that is 3,600 kilometers long. Climate Yukon Communities Most of Yukon has a dry subarctic Most of the population lives in climate. Whitehorse experiences average Whitehorse, however Yukon has several daily highs of 21C and average daily lows thriving communities throughout the of -22C. Whitehorse has little territory. From mountainous Haines precipitation with an average snowfall of Junctions to historic Dawson City, every 145 cm and 163 cm of rainfall. Yukon’s community offers beautiful scenery and dry, continental climate results in very that unique northern hospitality. The low humidity, so summers can be hot and following is a list of the Yukon dry while the winter cold is less harsh communities, and more information can than in damper climates. -

Resda Atlas: Summary of Yukon Mines

ReSDA Atlas: Summary of Yukon Mines Compilation of summary information of mines 2016 past and present for the Yukon ReSDA Atlas: Summary of Yukon Mines ReSDA Atlas: Summary of Yukon Mines COMPILATION OF SUMMA RY INFORMATION OF MI NES PAST AND PRESENT FOR THE YUKO N Bellekeno Silver Mine Brewery Creek Mine Casino Project Clinton Creek Mine Coffee Gold Project Eagle Gold Mine Elsa Mine Faro Mine Historic Keno Hill Mine District Ketza River Mine Mactung Project Minto Mine Mount Nansen Mine (Yukon) Tagish Lake/Mount Skukum Gold Project Sa Dena Hes (Mt. Hundere) Mine Tantalus Coal Mine Whitehorse Copper Belt Mines 1900-1920 Whitehorse Copper Belt Mines 1967-1982 Wolverine Mine BELLEKENO SILVER SUMMARY BELLEKENO Silver Mine Description of the mine The Bellekeno mine is a former silver mine located 330 kilometres north of Whitehorse in Yukon’s Keno Hill, which is classified as a polymetallic silver-lead-zinc vein district. It is one of the world’s highest-grade silver mines and during its latest production phase from 2011-2013 it was Canada’s only primary silver mine. Bellekeno is the first mine, among more than 35 mine sites, to be reopened in the historic Keno Hill district, which has not seen any production since 1989. United Keno Hill Mine Ltd. originally operated the Bellekeno mine during peak silver production in the Keno Hill district in the mid-1900s. Alexco Resources purchased the Keno Hill Silver District in 2006. It reclaimed Bellekeno and in 2011 began production at the mine. Operations were suspended in the fall of 2013 due to low silver price. -

Presentation-Yecpresentation E.Pdf

Good morning, Chairman Neufeld and committee members. Thank you for the invitation to present to you on Yukon Energy’s business and the issues facing us. I will refer you to the slide presentation which I believe you have a copy of. I am now turning to slide 2. 1 I’ll address three general topics in my presentation: 1. Firstly. I’ll provide an overview of Yukon Energy, our asset profile, our recent project history, and our current status. 2. Next, I’ll discuss the options that we are focusing on for new supplies of energy 3. And finally, I’ll touch on some of the challenges that we face. After my formal remarks, I’ll be happy to take any questions that you have. Moving now to slide 3. 2 Yukon Energy is one of two regulated utilities in the Yukon. We are responsible for the majority of electricity generation in the Territory, including 3 hydro facilities and a fleet of back‐up diesel generators. We also own and operate the majority of the electrical grid in the Territory. We distribute electricity to residential and commercial customers in a few of the grid‐connected communities outside of Whitehorse, including Dawson City, Mayo and Faro. We do not serve any remote off‐grid communities. ATCO Electric Yukon is the other regulated utility in the Yukon –they distribute power to residential and commercial customers here in Whitehorse, and they also provide power to a number of off‐grid communities, including Burwash Landing, Destruction Bay, Beaver Creek, Old Crow and Watson Lake. -

Filter to Retrieve Articles Related to Indigenous Peoples of the Yukon Territory from the OVID MEDLINE Database

Filter to Retrieve Articles Related to Indigenous Peoples of the Yukon Territory from the OVID MEDLINE Database Sandy Campbell, Marlene Dorgan and Lisa Tjosvold John W. Scott Health Sciences Library University of Alberta Copy and paste into the OVID MEDLINE search box: ((Carcross or (Tagish not meteorite*) or Champagne First Nation or Aishihik or Ehdiitat or Nacho Nyak Dun or Gwichya or Little Salmon or Carmacks or Nihtat or Selkirk First Nation or Ta'an Kwach'an or Tetlitn or Tr'ondek Hwech'in or White River First Nation or Vuntut or Yellowknives or (Hare adj2 (man or men or woman or women or child* or youth* or adult* or people* or person or persons or tribe or tribal or band or bands)) or Tanana or Tanana or Tutchone* or Denesuline or Tahltan or MacKenzie Valley or Old Crow or "Upper Liard" or "Eagle Plains" or "Keno City" or Carcross or Teslin or "Fort Selkirk" or Carmacks or Haines Junction or Dawson City or (Canad* or exp Canada/ and (Beaver Creek or Pelly or Destruction Bay or Watson Lake))) OR ((exp Indians, North American/ or exp Health Services, Indigenous/ or exp Medicine, Traditional/ or exp Shamanism/ or exp Ethnopharmacology/ or Indigenous* or Aboriginal* or Amerindian* or Autochtone* or Metis or First Nation or First Nations or exp Inuit/ or Inuit* or Chipewyan or Kaska or Kaskas or Tlingit or Dene or Gwich'in or Gwichin or Gwitchin or Kutchin* or Sahtu or Tlicho or Tli Cho or (traditional adj1 (medicine* or heal* or food* or health*)) or Urban Indian* or "on reserve" or "off reserve*"or country food* or shaman* or medicine m?n or medicine wom?n or treaty or treaties or ((native* or Indian or Indians) adj2 (person or persons or man or woman or men or women or child* or youth or youths or population* or people* or band or bands))) AND (exp Yukon Territory/ or Yukon* or (( Beaufort Sea or Whitehorse) and Canad*.mp.))) NOT (exp Alaska/ or Alaska* not ((exp Alaska/ or Alaska*) and (exp Yukon/ or Yukon*))) Not (Yukon-Kuskok* or lepus or geology* or stratigraphi* or subduction* or volcan* or Holocene or pleistocene).mp.) Notes: 1. -

Report on the Heritage Regions Workshop 9Am-4Pm, February 17, 2015 Old Firehall, Whitehorse

Report on the Heritage Regions Workshop 9am-4pm, February 17, 2015 Old Firehall, Whitehorse 1 Contents Overview .................................................................................................................................... 3 Points from Discussion/Group Exercises.................................................................................... 5 Keno/Mayo/Silver Trail Area ................................................................................................... 5 Watson Lake, Ross River/Faro Region ................................................................................... 6 Carmacks ............................................................................................................................... 7 Evaluation/Feedback.................................................................................................................. 8 Funding Sources Identified Through Discussion ........................................................................ 9 Continuing the Conversation/ Upcoming Events .......................................................................10 2 Overview This one-day workshop was hosted by the Yukon Historical & Museums Assocation (YHMA) and facilitated by Jim Mountain, Director of Regeneration Projects with the Heritage Canada National Trust. The workshop gave participants an overview of the Heritage Regions program. In addition to sharing news/events/happenings with communities and organizations, participants explored a variety of topics including land-based