Inning Can Change the World.” “And Did It?” “You Know As Much As I Do.”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tigers Make Big Trade, White Sox Win Game 7-4

SPORTS SATURDAY, AUGUST 2, 2014 Tigers make big trade, White Sox win game 7-4 Los Angeles avert three-game series sweep DETROIT: Moises Sierra had four hits, and Jose of last-place teams. The Rockies have lost four of Abreu and Adam Eaton added three apiece to lift five and 11 of 15 overall. Pedro Hernandez (0-1) the Chicago White Sox to a 7-4 victory over the allowed three runs and six hits in 5 2-3 innings in Detroit Tigers on Thursday. The game quickly his first start for Colorado. became a secondary concern in the Motor City Hector Rondon got three outs for his 14th save when the Tigers acquired star left-hander David in 17 opportunities. He retired three straight after Price from Tampa Bay in a three-team deal. Joakim Nolan Arenado and Justin Morneau singled to start Soria (1-4) - another pitcher recently acquired by the ninth. The Cubs made one trade on the non- Detroit - hit Paul Konerko with the bases loaded in waiver deadline day, sending utilityman Emilio the seventh to give the White Sox a 5-4 lead. Abreu Bonifacio, reliever James Russell and cash to extended his hitting streak to 20 games. Ronald Atlanta for catching prospect Victor Caratini. Belisario (4-7) got the win in relief, and Jake Petricka pitched the ninth for his sixth save. BLUE JAYS 6, ASTROS 5 Detroit’s Torii Hunter and JD Martinez hit back-to- Nolan Reimold hit two home runs, including a back homers in the third. tiebreaking solo shot in the ninth, and Toronto ral- lied for a win. -

IW Ancient Ways in Worship

VOLUME 55 ™ A DEEPER LOOK Ancient Ways In Worship ...INSIDE WORSHIP: YESTERDAY, TODAY AND FOREVER TOWARD A POSTMODERN LITURGY MAKING THE MUSIC OF THE PASSION VIOLINSPIRATION THE WORD IN WORSHIP PLUS: PRAYERS OF THE PAST FOR THE PRESENT Building On The Past Through all the movements of history, we worship a living God who is not a mute idol. He is alive, and He does move in the midst of your history and mine. He does new things in fresh ways, and thus we cannot remain still in our to worship Him. Though His nature is unchanging, He does unique things in every generation. Therefore, we must worship God in re- sponse to His immanent presence, His present nearness to us, in our day and according to our common languages of expres- sion. Whether we worship God in a Latin vesper or we worship Him in a modern day rap song, God is always to be worshiped in a living and non-static way. Today, the hearts of worshipers around the world are hunger- ing to reclaim connection with the worshipers of the Church through the ages. As you consider the challenges raised by TM drawing together our current worship expressions with those Volume 55 | February 2005 of the past, let’s remember three things: Publisher Firstly, we are all part of the redeemed, the great cloud of wit- Vineyard Music Global nesses, and so we stand inextricably linked with the saints of old, Editor actively waiting for the return of Christ and the establishment of Dan Wilt a new heaven and earth. -

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings November 21, 2012

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings November 21, 2012 CINCINNATI ENQUIRER Pitching is pricey, transactions By John Fay | 11/20/2012 12:17 PM ET Want to know why the Reds would be wise to lock up Homer Bailey and Mat Latos long-term? The Kansas City Royals agreed to a three-year deal with Jeremy Guthrie that pays him $5 million on 2013, $11 million in 2014 and $9 million in 2015. He went 8-12 with a 4.76 ERA and 1.41 WHIP. Bailey went 13-10 with a 3.68 ERA and a 1.24 WHIP. Latos went 14-4 with a 2.48 ERA and a 1.16 WHIP. It’s a bit apples and oranges: Guthrie is a free agent; Bailey is arbitration-eligible for the second time, Latos for the first. But the point is starting pitching — even mediocre starting pitching — is expensive. SIX ADDED: The Reds added right-handers Carlos Contreras, Daniel Corcino, Curtis Partch and Josh Ravin, left-hander Ismael Guillon and outfielder Yorman Rodriguez to the roster in order to protect them from the Rule 5 draft. Report: Former Red Frank Pastore badly hurt in motorcycle wreck By dclark | 11/20/2012 7:55 PM ET The Inland Valley Daily Bulletin is reporting that former Cincinnati Reds pitcher Frank Pastore, a Christian radio personality in California, was badly injured Monday night after being thrown from his motorcycle onto the highway near Duarte, Calif. From dailybulletin.com’s Juliette Funes: A 55-year-old motorcyclist from Upland was taken to a trauma center when his motorcycle was hit by a car on the 210 Freeway Monday night. -

Cuyahoga Falls Amateur Baseball Association

Cuyahoga Falls Amateur Baseball Association 2021 Spring Season Rulebook In partnership with the City of Cuyahoga Falls Parks and Recreation Department Page 2 of 28 Table of Contents Section Heading Page League Contact Information 4 Philosophy 5 A Registration 6 B League Drafts and Rosters 6 – 7 C Administration 7 D Safety 8 E Manager’s Responsibilities 9 F Uniforms 9 G Equipment 10 H Field and Game Preparation 11 – 12 I Player Participation 12 J General Game Rules 13 K Time Constraints (length, weather & mercy) 14 – 16 L Pitch Count 17 M Pitching Rules 18 N League Specific Rules: T Ball 19 O League Specific Rules: Coach Pitch 20 P League Specific Rules: H League 21 Q League Specific Rules: G League 22 R Protests 23 S Ejections 24 T Definitions 25 U Conduct Policy 26 V Significant Rule Changes 27 Page 3 of 28 Cuyahoga Falls Amateur Baseball Association CFABA Board Officers President Andrew Cole (330) 801-4599 [email protected] Vice President James Smith (330) 592-0626 [email protected] Secretary Ryan Kinnan (330) 814-1929 [email protected] Treasurer Mike DeSessa (440) 227-9524 [email protected] CFABA League Presidents T Ball Rich Dalman (440) 759-0884 [email protected] Coach Pitch Michelle Huston (330) 808-4450 [email protected] H League Greg Nowak (330) 730-4449 [email protected] G League Ryan Kinnan (330) 814-1929 [email protected] F League Mike Milhoan (330) 962-2394 [email protected] E League Steve DeArdo (419) 607-3100 [email protected] CFABA General -

A's News Clips, Wednesday, December 1, 2010 Power-Hungry

A’s News Clips, Wednesday, December 1, 2010 Power-hungry Oakland A's ready to wine, dine former Houston Astros slugger Lance Berkman By Joe Stiglich, Oakland Tribune A's officials were scheduled to have dinner Tuesday night in Houston with free agent Lance Berkman, two sources with knowledge of the situation confirmed to Bay Area News Group. Berkman, a switch-hitter who's slugged 327 homers over 12 seasons, is known to have been on the team's radar. Presumably, the A's view him as their designated hitter if they sign him. Berkman hit just .248 with 14 homers and 58 RBIs last season, which he began with the Houston Astros before being traded to the New York Yankees. But Berkman, who turns 35 in February, told Fox Sports last week that he's fully recovered from arthroscopic knee surgery that bothered him much of last season. He hit 25 homers as recently as 2009 for Houston. Adding power is the A's most pressing need. They would have a hole at DH if they decide not to tender a contract to Jack Cust, which is a strong possibility. The A's must decide by 9 p.m. Thursday (PT) whether to tender contracts to their 10 arbitration-eligible players, including Cust. Other logical non-tender candidates: outfielder Travis Buck, reliever Brad Ziegler and either of two third basemen -- Kevin Kouzmanoff or Edwin Encarnacion. It's believed the A's would consider signing Berkman to a one- or two-year deal, though the team doesn't comment on free- agent negotiations. -

2011 Topps Gypsy Queen Baseball

Hobby 2011 TOPPS GYPSY QUEEN BASEBALL Base Cards 1 Ichiro Suzuki 49 Honus Wagner 97 Stan Musial 2 Roy Halladay 50 Al Kaline 98 Aroldis Chapman 3 Cole Hamels 51 Alex Rodriguez 99 Ozzie Smith 4 Jackie Robinson 52 Carlos Santana 100 Nolan Ryan 5 Tris Speaker 53 Jimmie Foxx 101 Ricky Nolasco 6 Frank Robinson 54 Frank Thomas 102 David Freese 7 Jim Palmer 55 Evan Longoria 103 Clayton Richard 8 Troy Tulowitzki 56 Mat Latos 104 Jorge Posada 9 Scott Rolen 57 David Ortiz 105 Magglio Ordonez 10 Jason Heyward 58 Dale Murphy 106 Lucas Duda 11 Zack Greinke 59 Duke Snider 107 Chris V. Carter 12 Ryan Howard 60 Rogers Hornsby 108 Ben Revere 13 Joey Votto 61 Robin Yount 109 Fred Lewis 14 Brooks Robinson 62 Red Schoendienst 110 Brian Wilson 15 Matt Kemp 63 Jimmie Foxx 111 Peter Bourjos 16 Chris Carpenter 64 Josh Hamilton 112 Coco Crisp 17 Mark Teixeira 65 Babe Ruth 113 Yuniesky Betancourt 18 Christy Mathewson 66 Madison Bumgarner 114 Brett Wallace 19 Jon Lester 67 Dave Winfield 115 Chris Volstad 20 Andre Dawson 68 Gary Carter 116 Todd Helton 21 David Wright 69 Kevin Youkilis 117 Andrew Romine 22 Barry Larkin 70 Rogers Hornsby 118 Jason Bay 23 Johnny Cueto 71 CC Sabathia 119 Danny Espinosa 24 Chipper Jones 72 Justin Morneau 120 Carlos Zambrano 25 Mel Ott 73 Carl Yastrzemski 121 Jose Bautista 26 Adrian Gonzalez 74 Tom Seaver 122 Chris Coghlan 27 Roy Oswalt 75 Albert Pujols 123 Skip Schumaker 28 Tony Gwynn Sr. 76 Felix Hernandez 124 Jeremy Jeffress 2929 TTyy Cobb 77 HHunterunter PPenceence 121255 JaJakeke PPeavyeavy 30 Hanley Ramirez 78 Ryne Sandberg 126 Dallas -

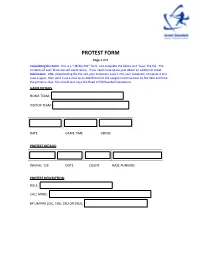

PROTEST FORM Page 1 of 2 Completing the Form: This Is a “Fillable PDF” Form

PROTEST FORM Page 1 of 2 Completing the Form: This is a “Fillable PDF” form. Just complete the blocks and “save” the file. The contents of each block are self-explanatory. If you need more space, just attach an additional sheet. Submission: After downloading the file into your computer, save it into your computer, complete it and save it again, then send it via e-mail as an attachment to the League Commissioner by the date and time the protest is due. You should also copy the Head of IAB Baseball Operations. GAME DETAILS HOME TEAM: VISITOR TEAM: DATE GAME TIME VENUE PROTEST DETAILS: INNING: T/B OUTS COUNT BASE RUNNERS PROTEST DESCRIPTION: RULE: CALL MADE: BY UMPIRE (UIC, 1BU, 2BU OR 3BU): PROTEST FORM Page 2 of 2 RECAP OF PLAY The protest shall be sent to the League Commissioner. A copy should also be sent to the Head of IAB Baseball Operations. No protest shall be considered on judgment decisions made by the umpire. In all protested games, the decision of the Protest Committee shall be final. Even if the protest is upheld, no replay of the game will be ordered unless in the opinion of the Protest Committee, the violation adversely affected the protesting team’s chances of winning the game. When a team’s manager protests a game, the protest shall not be recognized unless the umpires are notified at the time the play under protest occurs and before the next pitch, play or attempted play. All protests must be submitted in writing to the League Commissioner within 48 hours of the end of the protested game or the protest will not be recognized. -

Describing Baseball Pitch Movement with Right-Hand Rules

Computers in Biology and Medicine 37 (2007) 1001–1008 www.intl.elsevierhealth.com/journals/cobm Describing baseball pitch movement with right-hand rules A. Terry Bahilla,∗, David G. Baldwinb aSystems and Industrial Engineering, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0020, USA bP.O. Box 190 Yachats, OR 97498, USA Received 21 July 2005; received in revised form 30 May 2006; accepted 5 June 2006 Abstract The right-hand rules show the direction of the spin-induced deflection of baseball pitches: thus, they explain the movement of the fastball, curveball, slider and screwball. The direction of deflection is described by a pair of right-hand rules commonly used in science and engineering. Our new model for the magnitude of the lateral spin-induced deflection of the ball considers the orientation of the axis of rotation of the ball relative to the direction in which the ball is moving. This paper also describes how models based on somatic metaphors might provide variability in a pitcher’s repertoire. ᭧ 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Curveball; Pitch deflection; Screwball; Slider; Modeling; Forces on a baseball; Science of baseball 1. Introduction The angular rule describes angular relationships of entities rel- ative to a given axis and the coordinate rule establishes a local If a major league baseball pitcher is asked to describe the coordinate system, often based on the axis derived from the flight of one of his pitches; he usually illustrates the trajectory angular rule. using his pitching hand, much like a kid or a jet pilot demon- Well-known examples of right-hand rules used in science strating the yaw, pitch and roll of an airplane. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Indians Party Like It's 1997 After Winning Pennant

Indians party like it's 1997 after winning pennant Cleveland will host Game 1 of the World Series for first time in its history By Jordan Bastian / MLB.com | @MLBastian | 12:38 AM ET TORONTO -- They took turns passing the trophy around. A bottle in one hand and the hardware in the other, one by one, Cleveland's players savored their moment. They would stare at it, champagne dripping from the gold eagle that sits atop the black base, pausing for a moment before posing for photos. In that brief personal moment, the players probably thought about all that had to happen for the Indians to reach this stage, for that trophy to be placed in their arms. Wednesday's 3-0 win over the Blue Jays in Game 5 of the American League Championship Series, a victory that clinched the franchise's sixth AL pennant, gave the world a look at what has defined this Indians team all season long, and why it is now going to the World Series. "I'm just really happy that we're standing here today," said Indians president Chris Antonetti, as his players partied on the other side of Rogers Centre's visitors' clubhouse. "However we got here, I'm not sure I've reflected back on. But this team, the resiliency, the grit, the perseverance to overcome all that they've gone through over the course of the season ..." More champagne bottles popped behind him. "The guys we have are not focused on who's not here," he continued, "but focused on the guys that are here and [they] try to find a way to help them win. -

Is Major League Baseball Striking Out? In-Game Advertising and Its Effects on America’S Pastime

IS MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL STRIKING OUT? IN-GAME ADVERTISING AND ITS EFFECTS ON AMERICA’S PASTIME by Ashley M. Anderson A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of The Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2017 Approved by ________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Christopher Newman ________________________________ Reader: Dr. Allyn White ________________________________ Reader: Dr. Dwight Frink © 2017 Ashley Marie Anderson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For my brother, Austin. “Never let the fear of striking out keep you from playing the game.” -Babe Ruth iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my advisor, Dr. Christopher Newman, for his guidance and wisdom throughout this incredibly rewarding process. Thank you to Dr. Allyn White and Dr. Dwight Frink for reading diligently. Thank you to my parents, Darrin and Chris Anderson, for always supporting me and reminding me to stay balanced. Thank you to my brothers, Austin, Brennan, and Brady, for continually encouraging and inspiring me. Thank you to my fiancé, James Danforth, for reading draft after draft of my thesis and supporting me through endless mental breakdowns. Thank you to my friends for providing me with a wonderful home away from home. You have supported and encouraged me for as long as I can remember and I’m so grateful. iv ABSTRACT IS MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL STRIKING OUT? IN-GAME ADVERTISING AND ITS EFFECTS ON AMERICA’S PASTIME (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Newman) The purpose of this thesis is to determine the effectiveness of in-game advertisements at Major League Baseball games. Average attendance at Major League Baseball games has been steadily declining for years. -

Dayton Dragons 2014 Media Guide

DAYTON DRAGONS 2014 MEDIA GUIDE Nick Travieso Reds #1 Draft Pick, 2012 20142014 DDAYTONAYTON DDRAGONSRAGONS MMEDIAEDIA GGUIDEUIDE Table of Contents Front Office and Ownership Info Cincinnati Reds Front Office Info 2 Front Office Staff 88 Dragons Honors 3 Field Staff and Player Development 89 Fifth Third Field 4 2013 Draft Selections 90 Mandalay Baseball 5 Reds 2013 Minor League Player/Year 91 Mandalay Baseball Teams 6 Reds 2013 Organizational Leaders 93 2014 Reds Minor League Affiliates 94 2014 Dayton Dragons Field Staff 8 Miscellaneous & Media Information Player Bios 11 Dragons Medical Staff 99 2013 Dayton Dragons Review Dragons Media Relations 100 Season Review 20 and Media Outlets Opening Day Roster 22 MWL Telephone Directory 101 Transactions 23 Dragons “On the Air” 102 Statistics 24 2014 Media Regulations 103 Season-Highs, Misc. Stats 26 2014 Pre-Game Schedule and Ground 104 Game-by-Game 28 Rules Batter/Pitcher of the Month 30 Dragons Year-by-Year, All-Stars 31 Dayton Dragons Franchise Records All-Time Regular Season 32 Dragons Season Team Records 33 Dragons Single Game Team Records 34 Dragons Individual Game Records 35 Dragons Individual Season Records 36 Dragons Career Records 38 Dragons Year-by-Year Team Statistics 40 Dragons All-Time Roster 53 All-Time Managers, Coaches 56 All-Time Opening Day Lineups 57 Baseball America Top Prospect Lists 58 Dragons MLB Debuts 59 Midwest League/Minor Leagues General Information 62 MWL Team Pages 63 2013 Midwest League Recap 78 Midwest League Mileage Chart 83 Hotel Information 84 Minor League Baseball Directory 86 “The Streak,” Attendance Leaders 87 Jay Bruce The 2014 Dayton Dragons Media Guide was produced by the Dayton Dragons Media Relations Department and its entire contents are copyrighted by Dayton Dragons Professional Baseball, LLC.