Giulio Cesare in Egitto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Ellen T

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 21M.013J The Supernatural in Music, Literature and Culture Spring 2009 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Ellen T. Harris Alcina Opera seria: “serious opera”; the dominant form of opera from the late 17th century through much of the 18th; the texts are mostly based on history or epic and involve ethical or moral dilemmas affecting political and personal relationships that normally find resolution by the end Recitative: “recitation”; the dialogue or “spoken” part of the text, set to music that reflects the speed and intonation of speech; normally it is “simple” recitative, accompanied by a simple bass accompaniment; rarely in moments of great tension there can be additional orchestral accompaniments as in the incantation scene for Alcina (such movements are called “accompanied recitative”) Aria: the arias in opera seria are overwhelmingly in one form where two stanzas of text are set in the pattern ABA; that is, the first section is repeated after the second; during this repetition, the singer is expected to ornament the vocal line to create an intensification of emotion Formal units: individual scenes are normally set up so that a recitative section of dialogue, argument, confrontation, or even monologue leads to an aria in which one of the characters expresses his or her emotional state at that moment in the drama and then exits; this marks the end of the scene; scenes are often demarcated at the beginning -

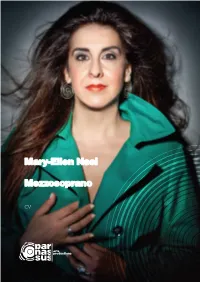

Mary-Ellen Nesi Mezzosoprano

Mary-Ellen Nesi Mezzosoprano CV CV PARNASSUS ARTS PRODUCTIONS Mary-Ellen Nesi Mezzosoprano A leading singer worldwide, Greek mezzo-so- prano Mary-Ellen Nesi has appeared at major international venues, including Bayerische Staatsoper, Carnegie Hall, Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Frankfurt Opera, Théâtre de Champs-Elysées, Avery Fisher Hall (NY), Strathmore Hall (Washington DC), Semperop- er (Dresden), Royal Opera of Versailles, Chun- gmu Art Hall (Seoul), Opéra National du Rhin, Theater an der Wien, Place des Arts (Mont- real), Concertgebouw, Opéra de Nice, Opera of Lausanne, Arriaga (Bilbao), Teatro de la Maes- tranza (Seville), Teatro Olimpico (Rome), Sao Carlos Opera (Lisbon), the Operas of Florence, Ferrara, Modena and Piacenza, the Wiesbaden Opera, Caio Melisso (Spoleto), the Baden Baden Festpielhaus. She has also appeared in renowned festivals around the world and she was founder and artistic director of the Opera Festival of Ancient Corinth (2003-2009). Mary-Ellen’s main focus lies in the baroque, classical and belcanto repertoire. She has performed more than 35 title and principal roles in operas by Monteverdi, Handel, Vivaldi, A.Scarlatti, Pergolesi, Porpora, Gluck, Paisiel- lo, Mozart, Rossini, Bizet, Donizetti, Bellini, R.Strauss, Verdi, Humperdinck, Mascagni, Massenet and contemporary composers. She has recorded Handel’s operas Oreste, Arianna in Creta, Tamerlano (ECHO KLASSIK 2008), Giulio Cesare, Alessando Severo, under George Petrou and Gluck’s Il Trionfo di Clelia, under G.Sigismondi (MDG), A.Scarlatti’s Tolo- meo e Alessandro(Archiv), Handel’s Berenice (Virgin) and a solo CD Salve Regina (DHM) under Alan Curtis, Vivaldi’s Il Farnace, under Diego Fasolis (Virgin), Christmas at San Marco under Peter Kopp (Berlin Classics). -

Handel Arias

ALICE COOTE THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET HANDEL ARIAS HERCULES·ARIODANTE·ALCINA RADAMISTO·GIULIO CESARE IN EGITTO GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL A portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner (1685–1749) 2 CONTENTS TRACK LISTING page 4 ENGLISH page 5 Sung texts and translation page 10 FRANÇAIS page 16 DEUTSCH Seite 20 3 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759) Radamisto HWV12a (1720) 1 Quando mai, spietata sorte Act 2 Scene 1 .................. [3'08] Alcina HWV34 (1735) 2 Mi lusinga il dolce affetto Act 2 Scene 3 .................... [7'45] 3 Verdi prati Act 2 Scene 12 ................................. [4'50] 4 Stà nell’Ircana Act 3 Scene 3 .............................. [6'00] Hercules HWV60 (1745) 5 There in myrtle shades reclined Act 1 Scene 2 ............. [3'55] 6 Cease, ruler of the day, to rise Act 2 Scene 6 ............... [5'35] 7 Where shall I fly? Act 3 Scene 3 ............................ [6'45] Giulio Cesare in Egitto HWV17 (1724) 8 Cara speme, questo core Act 1 Scene 8 .................... [5'55] Ariodante HWV33 (1735) 9 Con l’ali di costanza Act 1 Scene 8 ......................... [5'42] bl Scherza infida! Act 2 Scene 3 ............................. [11'41] bm Dopo notte Act 3 Scene 9 .................................. [7'15] ALICE COOTE mezzo-soprano THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET conductor 4 Radamisto Handel diplomatically dedicated to King George) is an ‘Since the introduction of Italian operas here our men are adaptation, probably by the Royal Academy’s cellist/house grown insensibly more and more effeminate, and whereas poet Nicola Francesco Haym, of Domenico Lalli’s L’amor they used to go from a good comedy warmed by the fire of tirannico, o Zenobia, based in turn on the play L’amour love and a good tragedy fired with the spirit of glory, they sit tyrannique by Georges de Scudéry. -

HOUSE of DREAMS Programme Notes

HOUSE OF DREAMS Programme Notes By Alison Mackay Tafelmusik’s House of Dreams is an evocation of rich and intimate experiences of the arts in the time of Purcell, Handel, Vivaldi and Bach. It is a virtual visit to London, Venice, Delft, Paris and Leipzig, where great masterpieces by European painters were displayed on the walls of five private homes. These houses were also alive with music, often played by the leading performers and composers of the day. Thus it was possible for visitors to drink tea in a Mayfair townhouse, observe how Watteau had applied his brushstrokes in the portrayal of a silk dress, and listen to Handel directing the rehearsal of a new gavotte. The five historical houses are all still in existence and our project has been planned as an international collaboration with their present owners and administrators. Invitations from the Handel House Museum (London), The Palazzo Smith Mangilli-Valmarana (Venice), the Golden ABC (Delft), the Palais-Royal (Paris) and the Bach Museum and Archive (Leipzig) to visit and photograph the houses have allowed us to portray for you the beautiful rooms where guests were entertained with art and music long ago. The title of the concert comes from the atmospheric description of the “House of Dreams” in Book 11 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In a dark cave where no cackling goose or crowing cockerel disturbs the still silence, the floor surrounding the ebony bed of the god of sleep is covered in empty dreams, waiting to be sent to the houses of mortals. The people, objects and animals in the theatre of our dreams are portrayed by the god’s children, Morpheus, Phantasos and Phobetor, who are re-imagined as messengers of artistic inspiration in the context of our script. -

Handel House Talent 2016-Final-1.Pdf

ABOUT THE PROGRAMME The programme will run from 30 September 2016 to 31 October 2017 with an end of year concert in December 2017. Over the course of the year the group of successful candidates will be offered: • At least two opportunities for each participant to perform at one of Handel House’s Thursday Live concerts, including working with Handel House staff on planning these concerts • An individual open masterclass for each participant, with a leading professional of their instrument, including feedback and tuition. Other participants of the scheme and members of the public will be invited to observe • A group tutorial by baroque specialist Laurence Cummings focusing on interpreting baroque pieces for performance • Two specialist workshops at Handel House on practical topics associated with becoming a successful professional musician (devising concert programmes, communicating with audiences, promotion, dealing with agents, managing finances etc). External experts will be invited to lead these • Opportunities to practice and rehearse at Handel House in their own time – HANDEL HOUSE whenever rehearsal space is available • A final showcase concert at the end of the year for the six participants, to an invited audience including people with interest and influence in the world of classical music performance. This concert is to be devised, talent organised and created by the participants as a group, with back-up from Handel House staff where needed • Promotion as ‘alumni’ of the HH Talent Programme on our website, on Handel House will select singers and programme notes provided at Handel House concerts and other marketing instrumentalists with a particular interest in material produced by Handel House performing music from the baroque period to benefit from this free, year-long programme. -

Jonathan Leif Thomas, Countertenor Dr

The University of North Carolina at Pembroke Department of Music Presents Graduate Lecture Recital Jonathan Leif Thomas, countertenor Dr. Seung-Ah Kim, piano Presentation of Research Findings Jonathan Thomas INTERMISSION Dove sei, amato bene? (from Rodelinda).. George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Ch'io mai vi possa (from Siroe) fl fervido desiderio .Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835) Ma rendi pur contento Now sleeps the crimson petal.. .. Roger Quilter (1877-1953) Blow, blow, thou winter wind Pie Jesu (from Requiem) .. Andrew Lloyd Webber Dr. Jaeyoon Kim, tenor (b.1948) THESIS COMMITTEE Dr. Valerie Austin Thesis Advisor Dr. Jaeyoon Kim Studio Professor Dr. Jose Rivera Dr. Katie White This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in Music Education. Jonathan Thomas is a graduate student of Dr. Valerie Austin and studies voice with Dr. Jaeyoon Kim. As a courtesy to the performers and audience, please adjust all mobile devices for no sound and no light. Please enter and exit during applause only. March 27,2014 7:30 PM Moore Hall Auditorium This publication is available in alternative formats upon request. Please contact Disability Support Services, OF Lowry Building, 521.6695. Effective Instructional Strategies for Middle School Choral Teachers: Teaching Middle School Boys to Sing During Vocal Transition UNCP Graduate Lecture Recital Jonathan L. Thomas / Abstract Teaching vocal skills to male students whose voices are transitioning is an undertaking that many middle school choral teachers find challenging. Research suggests that one reason why challenges exist is because of teachers' limited knowledge about the transitioning male voice. The development of self-identity, peer pressure, and the understanding of social norms, which will be associated with psychological transitions for this study, is another factor that creates instructional challenges for choral teachers. -

Giulio Cesare Music by George Frideric Handel

Six Hundred Forty-Third Program of the 2008-09 Season ____________________ Indiana University Opera Theater presents as its 404th production Giulio Cesare Music by George Frideric Handel Libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym (adapted from G. F. Bussani) Gary Thor Wedow,Conductor Tom Diamond, Stage Director Robert O’Hearn,Costumes and Set Designer Michael Schwandt, Lighting Designer Eiddwen Harrhy, Guest Coach Wendy Gillespie, Elisabeth Wright, Master Classes Paul Elliott, Additional Coachings Michael McGraw, Director, Early Music Institute Chris Faesi, Choreographer Adam Noble, Fight Choreographer Marcello Cormio, Italian Diction Coach Giulio Cesare was first performed in the King’s Theatre of London on Feb. 20, 1724. ____________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, February Twenty-Seventh Saturday Evening, February Twenty-Eighth Friday Evening, March Sixth Saturday Evening, March Seventh Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu Cast (in order of appearance) Giulio Cesare (Julius Caesar) . Daniel Bubeck, Andrew Rader Curio, a Roman tribune . Daniel Lentz, Antonio Santos Cornelia, widow of Pompeo . Lindsay Ammann, Julia Pefanis Sesto, son to Cornelia and Pompeo . Ann Sauder Archilla, general and counselor to Tolomeo . Adonis Abuyen, Cody Medina Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt . Jacqueline Brecheen, Meghan Dewald Nireno, Cleopatra’s confidant . Lydia Dahling, Clara Nieman Tolomeo, King of Egypt . Dominic Lim, Peter Thoresen Onstage Violinist . Romuald Grimbert-Barre Continuo Group: Harpsichord . Yonit Kosovske Theorbeo, Archlute, and Baroque Guitar . Adam Wead Cello . Alan Ohkubo Supernumeraries . Suna Avci, Joseph Beutel, Curtis Crafton, Serena Eduljee, Jason Jacobs, Christopher Johnson, Kenneth Marks, Alyssa Martin, Meg Musick, Kimberly Redick, Christiaan Smith-Kotlarek, Beverly Thompson 2008-2009 IU OPERA theater SEASON Dedicates this evening’s performance of by George Frideric Handel Giulioto Georgina Joshi andCesare Louise Addicott Synopsis Place: Egypt Time: 48 B.C. -

The Enchanted Island

THE ENCHANTED ISLAND Provenance of Musical Numbers. Updated 12/11/2013 ACT I: Overture (Handel: Alcina) 1. a. My Ariel… (Prospero, Ariel); b. “Ah, if you would earn your freedom” (Prospero) (Vivaldi: Cessate, omai cessate, cantata, RV 684 – “Ah, ch’infelice sempre”) 2. a. My master, generous master…; b. “I can conjure you fire” (Ariel) (Handel: Il trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno, oratorio, HWV 46a, Part I – “Un pensiero nemico di pace” and preceding recit) 3. a. Then what I desire…; b. Your last masterpiece? (Prospero, Ariel) 4. a. There are times when the dark side…; b. “Maybe soon, maybe now” (Sycorax, Caliban) (Handel: Teseo, HWV 9, Act V, scene 1 – “Morirò, ma vendicata”) 5. a. The blood of a dragon…; b. “Stolen by treachery” (Caliban) (Handel: La Resurrezione, oratorio, HWV 47, Part I, scene 1 – “O voi, dell’Erebo”) 6. a. Miranda! My Miranda!... (Prospero, Miranda); b. “I have no words for this feeling” (Miranda) (Handel: Notte placida e cheta, cantata, HWV 142, part 2 – “Che non si dà”) 7. a. My master’s books...; b. “Take salt and stones” (Ariel) (Based on Rameau: Les fêtes d’Hébé, Deuxième entrée: La Musique, scene 7 ‐ “Aimez, aimez d'une ardeur mutuelle”) 8. Quartet: “Days of pleasure, nights of love” (Helena, Hermia, Demetrius, Lysander) (Handel: Semele, HWV 58, Act I, scene 4 ‐ “Endless pleasure, endless love”) 9. The Storm…(Chorus) (Campra: Idoménée, Act II, scene 1 – “O Dieux! O justes Dieux!”) 10. I’ve done as you commanded (Ariel, Prospero) (Handel: La Resurrezione, oratorio, HWV 47, Part II, Scene 2 – recit: “Di rabbia indarno freme”) 11. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XVI, Number 1 April 2001 HANDEL’S SCIPIONE AND THE NEUTRALIZATION OF POLITICS1 This is an essay about possibilities, an observation of what Handel and his librettist wrote rather than what was finally performed. Handel composed his opera Scipione in 1726 for a text by Paolo Rolli, who adapted a libretto by Antonio Salvi written for a Medici performance in Livorno in 1704.2 Handel’s and Rolli’s version was performed at the King’s Theater in the Haymarket for the Royal Academy of Music.3 The opera has suffered in critical esteem not so much from its own failings as from its proximity in time to the great productions of Giulio Cesare, Tamerlano and Rodelinda which preceeded it. I would like to argue, however, that even in this opera Handel and Rolli were working on an interesting idea: a presentation of Roman historical material in ways that anticipated the ethical discussions that we now associate with the oratorios. If that potential was undermined by what was finally put on stage, it is nevertheless interesting to observe what might have been. Narrative material from the Roman republic was potentially difficult on the English stage of the early eighteenth century. The conquering heroes of the late Roman republic particularly—Sulla, Pompey, and especially Caesar—might most easily be associated with the monarch; but these historical figures were also tainted by the fact that they could be identified as tyrants responsible for demolishing republican freedom. Addison’s Cato had caused a virtual riot in the theatre in 1713, as Whigs and Tories vied to distance themselves from the (unseen) villain Caesar and claim the play’s stoic hero Cato as their own. -

Handel Newsletter-2/2001 Pdf

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XV, Number 3 December 2000 MHF 2001 The 2001 Maryland Handel Festival & Conference marks the conclusion of the Festival’s twenty-year project of performing all Handel’s dramatic English oratorios in order of composition. With performances of THEODORA, May 4 and JEPHTHA, May 6 conducted by Paul Traver, we welcome back to the MHF stage soloists from previous seasons including: Linda Mabbs and Sherri Karam, soprano; Lorie Gratis and Leneida Crawford, mezzo-soprano; Derek Lee Ragin, countertenor; Charles Reid, tenor; Philip Collister, bass; with the Smithsonian Chamber Orchestra, Kenneth Slowik, Music Director; the University of Maryland Chorus, Edward Maclary, Music Director; and The Maryland Boys Choir, Joan Macfarland, director. As always, the American Handel Society and Maryland Handel Festival will join forces to present a scholarly conference, which this year brings together internationally renowned scholars from Canada, England, France, Germany, and the United States, and which will consist of four conference sessions devoted to various aspects of Handel studies today. Special events include the Howard Serwer Lecture (formerly the American Handel Society Lecture), to be presented on Saturday May 5 by the renowned HANDEL IN LONDON scholar Nicholas Temperley, the American Handel Society Dinner, later that same evening, and the pre- By 2002 there will be at least six different institutions concert lecture on Sunday May 6. in London involved with Handel: The conference and performances will take place in 1. British Library the new Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center at the University of Maryland; lodgings will once again be located at the Inn and Conference Center, University The British Library, holding the main collection of of Maryland University College, where the Society Handel autographs, is (together with the Royal dinner will also take place. -

Christophe Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques Unearth the Impropriety of the Gods in a Staging of Legrenzi’S La Divisione Del Mondo

Christophe Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques unearth the impropriety of the Gods in a staging of Legrenzi’s La Divisione del Mondo 8-16 February 1, 3 March 9 March Strasbourg Mulhouse Colmar 20-27 March Legrenzi La 13, 14 April Nancy Divisione del Mondo Versailles “La Divisione del Mondo shows us a most complicated and modern dysfunctional family - the Roman Gods seem to offer a hilarious mirror of our human misconduct and failures.” - Jetske Mijnssen Christophe Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques tour Giovanni Legrenzi’s rarely-performed La Divisione del Mondo in France from 8 February to 14 April. Directed by Jetske Mijnssen, fifteen performances will be given from Strasbourg to Versailles, via Mulhouse, Colmar, and Nancy, in a co-production with the Opéra national du Rhin and the Opéra national de Lorraine. Seen in its first modern staging in France, the revival of La Divisione del Mondo forms part of Les Talens Lyriques’ season theme, The Temptation of Italy, tracking Italian influences on French writing. Venetian opera had influenced French operatic tradition since its inception, and the only surviving score for La Divisione del Mondo is found in the Bibliothèque nationale de Paris. First performed in a lavish staging with great success at the Venetian Teatro San Salvador in 1675, La Divisione del Mondo depicts the division of the world following the victory of the Olympian gods over the Titan deities: the world inhabited by Madeline Miller’s novel Circe, recently a runaway best-seller in both the New York Times and The Sunday Times. Far from being a banal tale of morals and virtues, instead it unearths dreadful impropriety, with the goddess Venus leading all the other gods (with the exception of Saturn) through a series of moral temptations into debauchery.