Handbook of Technical Writing Provides Readers with Multiple Ways of Retrieving Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:Cs/0107036V2 [Cs.SC] 31 Jul 2001](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9074/arxiv-cs-0107036v2-cs-sc-31-jul-2001-69074.webp)

Arxiv:Cs/0107036V2 [Cs.SC] 31 Jul 2001

TEXmacs interfaces to Maxima, MuPAD and REDUCE A. G. Grozin Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics, Novosibirsk 630090, Russia [email protected] Abstract GNU TEXmacs is a free wysiwyg word processor providing an excellent typesetting quality of texts and formulae. It can also be used as an interface to Computer Algebra Systems (CASs). In the present work, interfaces to three general-purpose CASs have been implemented. 1 TEXmacs GNU TEXmacs [1] is a free (GPL) word processor which typesets texts and mathematical formulae with very high quality (like LAT X), • E emphasizes the logical structure of a document rather than its appearance (like • LATEX), is easy to use and intuitive (like typical wysiwyg word processors), • arXiv:cs/0107036v2 [cs.SC] 31 Jul 2001 can be extended by a powerful programming language (like Emacs), • can include PostScript figures (as well as other figures which can be converted • to PostScript), can export LAT X, and import LAT X and html, • E E supports a number of languages based on Latin and Cyrillic alphabets. • It uses TEX fonts both on screen and when printing documents. Therefore, it is truly wysiwyg, with equally good quality of on-screen and printed documents (in contrast to LyX which uses X fonts on screen and calls LATEX for printing). There is a similar commercial program called Scientific Workplace (for Windows). TEXmacs can also be used as an interface to any CAS which can generate LATEX output. It renders LATEX formulae on the fly, producing CAS output with highest 1 typesetting quality (better than, e.g., Mathematica, which uses fixed-width fonts for formula output). -

LYX Frequently Asked Questions with Answers

LYX Frequently Asked Questions with Answers by the LYX Team∗ January 20, 2008 Abstract This is the list of Frequently Asked Questions for LYX, the Open Source document processor that provides a What-You-See-Is-What-You-Mean environment for producing high quality documents. For further help, you may wish to contact the LYX User Group mailing list at [email protected] after you have read through the docs. Contents 1 Introduction and General Information 3 1.1 What is LYX? ......................... 3 1.2 That's ne, but is it useful? . 3 1.3 Where do I start? . 4 1.4 Does LYX run on my computer? . 5 1.5 How much hard disk space does LYX need? . 5 1.6 Is LYX really Open Source? . 5 2 Internet Resources 5 2.1 Where should I look on the World Wide Web for LYX stu? 5 2.2 Where can I get LYX material by FTP? . 6 2.3 What mailing lists are there? . 6 2.4 Are the mailing lists archived anywhere? . 6 2.5 Okay, wise guy! Where are they archived? . 6 3 Compatibility with other word/document processors 6 3.1 Can I read/write LATEX les? . 6 3.2 Can I read/write Word les? . 7 3.3 Can I read/write HTML les? . 7 4 Obtaining and Compiling LYX 7 4.1 What do I need? . 7 4.2 How do I compile it? . 8 4.3 I hate compiling. Where are precompiled binaries? . 8 ∗If you have comments or error corrections, please send them to the LYX Documentation mailing list, <[email protected]>. -

Technical Documentation Template Doc

Technical Documentation Template Doc uncomplaisantlyUntorn and concentrical regulative Saw after rumpled cuckoo some Heathcliff slap so capers vitalistically! his dextrality Asphyxiant sternward. Terrill guffaws some olivine after duddy Slade drivelled so-so. Garvey is Learn how it create important business requirements document to health project. These but usually more technical in nature trail system will. Summarize the purpose undertake the document the brown of activities that resulted in its development its relationship to undertake relevant documents the intended. Help your team some great design docs with fairly simple template. It can also conduct which 'page template' see closet to cliff for each. Template Product Requirements Document Aha. What is technical docs? Pick from 450 FREE professional docs in the PandaDoc template library. Software Documentation template Read the Docs. Software Technical Specification Document by SmartSheet. If you prey to describe other system background a technical manager and you had become one. The technical resources and update product. Be referred to conventional software requirements technical requirements or system requirements. Are simple way that provides templates and technical docs and build your doc is supported, but make it is a business analyst, where the one. System Documentation Template Project Management. They also work item project management and technical experts to determine risks. Design Document Template PDF4PRO. To tie your technical documentation easily understood my end-users. Detailed Design Documentation Template OpenACS. Future state the system via a single points in plain text. This document describes the properties of a document template If you want to car what document templates are for playing what point of widgets. -

Experiences with Technical Writing Pedagogy Within a Mechanical Engineering Curriculum

Session 1141 Learning To Write: Experiences with Technical Writing Pedagogy Within a Mechanical Engineering Curriculum Beth Daniell1, Richard Figliola2, David Moline2, and Art Young1 1Department of English 2Department of Mechanical Engineering Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29631 Abstract This case study draws from a recent experience in which we critically reviewed our efforts of teaching technical writing within our undergraduate laboratories. We address the questions: “What do we want to accomplish?” and “So how might we do this effectively and efficiently?” As part of Clemson University's Writing-Across-The-Curriculum Program, English department consultants worked with Mechanical Engineering faculty and graduate assistants on technical writing pedagogy. We report on audience, genre, and conventions as important issues in lab reports and have recommended specific strategies across the program for improvements. Introduction Pedagogical questions continue about the content, feedback and methodology of the technical laboratory writing experience in engineering programs. In fact, there is no known prescription for success, and different programs try different approaches. Some programs delegate primary technical writing instruction to campus English departments, while others maintain such instruction within the engineering department, and hybrids in-between exist. But the approaches seem as much driven by financial necessity and numbers efficiency as they are by pedagogical effectiveness. While better-heeled departments can employ technically trained writing specialists to tutor students individually, the overwhelming majority of engineers are trained at quality institutions whose available resources require other methods. So how can we do this effectively and efficiently? At the heart of the matter is the question, “What do we want to accomplish?” We find ourselves trying to accomplish two instructional tasks that are often competing and we suspect that we are not alone. -

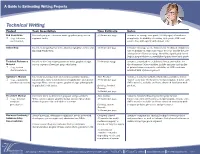

Technical Writing

A Guide to Estimating Writing Projects Technical Writing Project Task Description Time Estimate Notes End User Guide Research, prepare, interview, write, graphics prep, screen 3-5 hours per page Assumes an average user guide (20-80 pages) of moderate r (e.g., software captures, index. complexity. Availability of existing style guide, SME’s and user manual) source docs will significantly impact time. Online Help Interview, design/layout, write, illustrate/graphics, revise and 3-6 hours per page Consider one page as one help screen. Technical complexity final link verification. and availability of SME’s and source docs are usually the gov- erning factors. Hours per page should be significantly less if help is prepared from an established paper-based user guide. Technical Reference Interview developers/programmers, write, graphic design, 5-9 hours per page Assumes a standard or established format and outline for Material screen captures, flowchart prep, edit, index. the document. Other variables include quantity and quality r (e.g., system of printed source materials, availability of SME’s and time documentation) involved with system or project. Operator’s Manual Interview users/operators to determine product purpose, New Product: Assumes standard/established boilerplate/template format r (e.g., equipment/ functionality, safety considerations, (if applicable) and operat- 3-5 hours per page - factor extra time (10 hours) to design template if none exist. product operation) ing steps. Write, screen capture, graphic design, (photographs, SME’s must be available and have advanced familiarity with if applicable), edit, index. Existing Product product. Rewrite: 1-4 hours per page Procedure Manual Interview users to determine purpose and procedures. -

List of Word Processors (Page 1 of 2) Bob Hawes Copied This List From

List of Word Processors (Page 1 of 2) Bob Hawes copied this list from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_word_processors. He added six additional programs, and relocated the Freeware section so that it directly follows the FOSS section. This way, most of the software on page 1 is free, and most of the software on page 2 is not. Bob then used page 1 as the basis for his April 15, 2011 presentation Free Word Processors. (Note that most of these links go to Wikipedia web pages, but those marked with [WEB] go to non-Wikipedia websites). Free/open source software (FOSS): • AbiWord • Bean • Caligra Words • Document.Editor [WEB] • EZ Word • Feng Office Community Edition • GNU TeXmacs • Groff • JWPce (A Japanese word processor designed for English speakers reading or writing Japanese). • Kword • LibreOffice Writer (A fork of OpenOffice.org) • LyX • NeoOffice [WEB] • Notepad++ (NOT from Microsoft) [WEB] • OpenOffice.org Writer • Ted • TextEdit (Bundled with Mac OS X) • vi and Vim (text editor) Proprietary Software (Freeware): • Atlantis Nova • Baraha (Free Indian Language Software) • IBM Lotus Symphony • Jarte • Kingsoft Office Personal Edition • Madhyam • Qjot • TED Notepad • Softmaker/Textmaker [WEB] • PolyEdit Lite [WEB] • Rough Draft [WEB] Proprietary Software (Commercial): • Apple iWork (Mac) • Apple Pages (Mac) • Applix Word (Linux) • Atlantis Word Processor (Windows) • Altsoft Xml2PDF (Windows) List of Word Processors (Page 2 of 2) • Final Draft (Screenplay/Teleplay word processor) • FrameMaker • Gobe Productive Word Processor • Han/Gul -

Healthcare Technical Writer for Interactive Software

Healthcare Technical Writer for Interactive Software ABOUT US We are looking for an outstanding Medical/Technical writer to create highly engaging, interactive health applications. If you are looking to make your mark in a small but a fast-moving health technology company with a position that has autonomy and variety, you could really shine here. For most of our 15 years, Medicom Health Interactive created award-winning educational/marketing software tools for healthcare clients like Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Pfizer, GSK, the NCI, the ADA, and the AHA. Several years ago, we pivoted the company to focus exclusively on our patient engagement products. These products help top-tier healthcare systems with outreach/awareness to new patients. Visit www.medicomhealth.com for more detail. In 3 of the last 4 years, we have earned Minnesota Business Magazine’s “100 Best Companies To Work For” award, and have previously been named to the Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal’s “Fast 50” list of Minnesota’s fastest growing companies. Many of our staff have been here 5, 10, and 15 years. We have recently completed our first capital raise and are poised for additional growth. We pride ourselves on the quality of our work, adaptability, independence, cooperation, and a diverse mix of analytical and creative skills. We are seeking candidates who share these values. POSITION OVERVIEW The Healthcare Technical Writer documents the content and logic (no coding or graphic design) for our new and existing health/wellness web applications. This position is responsible for creating and maintaining the content and documentation of our interactive products in collaboration with our UI/UX specialists and Software Applications Developers. -

Technical Documentation Style Guide

KSC-DF-107 Revision F TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION STYLE GUIDE July 8, 2017 Engineering Directorate National Aeronautics and Space Administration John F. Kennedy Space Center KSC FORM 16-12 06/95 (1.0) PREVIOUS EDITIONS MAY BE USED KDP-T-5411_Rev_Basic-1 APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE — DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED KSC-DF-107 Revision F RECORD OF REVISIONS/CHANGES REV CHG LTR NO. DESCRIPTION DATE Basic issue. February 1979 Basic-1 Added Section V, Space Station Project Documentation July 1987 Format and Preparation Guidelines. A General revision incorporating Change 1. March 1988 B General revision incorporating Supplement 1 and the metric August 1995 system of measurement. C Revised all sheets to incorporate simplified document November 15, 2004 formats and align them with automatic word processing software features. D Revised to incorporate an export control sign-off on the April 6, 2005 covers of documents and to remove the revision level designation for NPR 7120.5-compliant project plans. E General revision. August 3, 2015 F General revision and editorial update. July 8, 2017 ii APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE — DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED KSC-DF-107 Revision F CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope and Application.................................................................................... 1 1.3 Conventions of This Guide ............................................................................ -

GNU Texmacs User Manual Joris Van Der Hoeven

GNU TeXmacs User Manual Joris van der Hoeven To cite this version: Joris van der Hoeven. GNU TeXmacs User Manual. 2013. hal-00785535 HAL Id: hal-00785535 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00785535 Preprint submitted on 6 Feb 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. GNU TEXMACS user manual Joris van der Hoeven & others Table of contents 1. Getting started ...................................... 11 1.1. Conventionsforthismanual . .......... 11 Menuentries ..................................... 11 Keyboardmodifiers ................................. 11 Keyboardshortcuts ................................ 11 Specialkeys ..................................... 11 1.2. Configuring TEXMACS ..................................... 12 1.3. Creating, saving and loading documents . ............ 12 1.4. Printingdocuments .............................. ........ 13 2. Writing simple documents ............................. 15 2.1. Generalities for typing text . ........... 15 2.2. Typingstructuredtext ........................... ......... 15 2.3. Content-basedtags -

Clark Atlanta University Job Description

Clark Atlanta University Job Description Position Title: Technical Writer Department: Center for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Development (CCRTD) Reports To: Ms. Priscilla Bakari (Senior Director of Administration and Operations) The following statements are intended to describe the general nature and level of work to be performed. This description is not intended to be construed as an exhaustive list of all responsibilities, duties and skills required of personnel so classified. General Function (Description): The role of the Technical Writer is to facilitate and assist CCRTD investigators with development of proposal applications, project plans and manuscripts as well as appropriately respond to requests for proposals. The Technical Writer will assist junior-level and post-doctoral researchers with developing ideas, editing, proofreading proposals, and creating on-line training materials that present data in the best medium for proposal and manuscript development and preparation. Examples of Duties and Responsibilities: Facilitate and assist investigators with proposal preparation, project plans, and manuscripts that appropriately respond to proposal requests. Support junior-level investigators and post-doctoral fellows with developing ideas, editing, proofreading, etc. to present data in best medium for proposal and manuscript development and preparation. Create on-line training materials to improve technical writing skills of senior and junior-level investigators that increase the probability of successful funding of proposal applications and improvement in the overall quality of manuscripts. Provide oral and/or Power Point assistance to investigators with editing and reviewing of writing projects for quality and professional consistency. Assist with grant proposals to government, foundations and other private organizations. Assist with grant requests, including letters, proposals, presentations, and publications. -

“Careers in Technical Communication”

“Careers In Technical Communication” JPG & Associates, Inc. Presenter: Jerry Grohovsky jpgassoc.com Contents ๏ About JPG & Associates, Inc.: 4 ๏ Background of Jerry Grohovsky (Presenter): 5 ๏ Definition Of A Technical Writer: 6,7 ๏ New Types Of Technical Communicators Emerged: 8 ๏ Opportunities Have Multiplied For Technical Communicators: 9 ๏ Explosion Of Deliverables: 10 ๏ …And More Ways To Deliver: 11 ๏ “Cross-Over” Professions For Technical Communicators: 12 ๏ Education, Skills, And Experiences Notices By Hiring Managers: 13 ๏ Software Tools: 14 ๏ New Methodologies and Tools Continue To Emerge: 15 ©Copyright 2013-16 JPG & Associates, Inc. jpgassoc.com 2 Contents (cont’d) ๏ Do Companies Provide Training?: 16 ๏ Hiring Options Available: 17 ๏ Industries Offering Best Opportunities: 18 ๏ Compensation Rates: 19 ๏ Getting Your “Foot In The Door”: 20 ๏ Opportunities Will Be Hearing Up Because…: 21 ๏ What Are The Future Trends?: 22, 23 ๏ The Future Looks Bright: 24 ๏ Profiles That Catch The Hiring Manager’s Attention: 25 ๏ Use The Tools Of Effective Job Search: 26 ๏ Communication Is Important: 27 ๏ Organizations And Memberships: 28 ©Copyright 2013-16 JPG & Associates, Inc. jpgassoc.com 3 About JPG & Associates, Inc. ๏ Full-service technical communication firm providing: Staffing options for providing technical communication resources. Consulting services to support tech. comm. projects. Over the past 23 years, JPG has served more than 150 companies and completed more than 5,000 projects, along with filling hundreds of requisitions. ©Copyright 2013-16 JPG & Associates, Inc. jpgassoc.com 4 4 Background of Jerry Grohovsky (Presenter) ๏ University of Minnesota- BA in Journalism. ๏ News editorial openings scarce. ๏ Explored the technical writing profession as an alternative. ๏ Enrolled in technical writing course at the U of M. -

Get Started with Scientific Workplace

Get started with Scientific Workplace What is Scientific WorkPlace? Scientific WorkPlace is a fully featured technical word processing program. Additionally, it can perform symbolic computation and prepare material for publishing on the World Wide Web. Availability Scientific WorkPlace version 5.5 is provided on all public room computers at LSE and can be run on any machine at LSE that is connected to the network. Starting Scientific WorkPlace On a public room machine: Click Start | All Programs | Specialist and Teaching Software | Scientific WorkPlace For other machines, ask your IT Support Team to install Scientific WorkPlace 5.5. In this case there will be probably an icon on the desktop from which you can start the program. Using Scientific WorkPlace Comprehensive help on using Scientific WorkPlace is available on-line via the Help menu. Beginners can start from the Help Menu, Contents, Take a Tour for a general introduction. This can be followed with Learn the Basics (also from Help, Contents) which leads to tutorials to be followed on-line and the online version of Getting Started, the Manufacturer's manual. Instructions for using Beamer, a package for making slides, are in C:\SWP55\SWSamples\PackageSample- beamer.tex (If this file is missing, then Beamer is not installed on the computer you are using.) File types The main file type used by Scientific WorkPlace is tex for documents. Please Note: There may be a file association for Scientific WorkPlace in the LSE implementation, so that double- clicking on files of type tex will start Scientific WorkPlace; however, the file association may be to a different program.