A Brief History of Grindleton - by Chris Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waddington and West Bradford Church of England Primary School ADMISSION ARRANGEMENTS for September 2022

Waddington and West Bradford Church of England Primary School ADMISSION ARRANGEMENTS For September 2022 Making an application Applications for admission to the school for September 2022 should be made on-line at www.lancashire.gov.uk/schools or on the Common Application Form between September 2021 and 15th January 2022. It is not normally possible to change the order of your preferences for schools after the closing date. Parents must complete the Local Authority form, stating three preferences. Parents who wish their application to this Church school to be considered against the faith criteria should also complete the supplementary form. If the school is oversubscribed, a failure to complete the supplementary form may result in your application for a place in this school being considered against lower priority criteria as the Governing Body will have no information upon which to assess the worship attendance. The Supplementary Information Form is available from the school. Letters informing parents of whether or not their child has been allocated a place will be sent out by the Local Authority in April 2022. Parents of children not admitted will be informed of the reason and offered an alternative place by the Authority. Admission procedures Arrangements for admission have been agreed following consultation between the governing body, the Diocesan Board of Education, Local Authorities and other admissions authorities in the area. The number of places available for admission to the Reception class in the year 2022 will be a maximum of 30. The governing body will not place any restrictions on admissions to the reception class unless the number of children for whom admission is sought exceeds their admission number. -

NEW: Gisburn Forest & Stocks Adventure

Welcome to Gisburn Forest and Stocks Explore in the Forest of Bowland AONB Get closer to nature and explore restored, traditional You'll encounter beautiful broadleaved and mixed conifer wildflower meadows - Bell Sykes - the county's woods, magnificent hay meadows, amazing views and designated Coronation Meadow. invigorating activities for all. Heritage Highlights - at Stocks Reservoir Wildlife for all Seasons – Stocks car park you can see the foundations of Reservoir is a haven for wildlife - there the original St. James' Church, which was are a range of woodland and upland part of the village of Stocks-in-Bowland birds, wildfowl and waders. In winter in the parish of Dale Head. Five hundred watch the spectacular starling displays people were living in the parish when it or perhaps encounter a passing osprey was established in 1872. The village and or the massed toad spawning in spring. church were demolished during the In the summer months head to the construction of Stocks Reservoir in the Hub and check the pools near the early part of the 20th century and the centre for dragonflies and damselflies. church re-built in 1938 further along the road. You can find out more about the For young wildlife spotters, download St James Church, Gisburn Forest work to uncover the church footprint on the seasonal quizzes from our website Stocks Reservoir www.forestofbowland.com/Family-Fun the information panels in the car park. Bowland by Night - The landscapes of Wild brown trout are also available at Designated in 1964 and covering 803 marked trails there is a skills loop at the Bell Sykes Hay Meadow © Graham Cooper the Forest of Bowland are captivating Bottoms Beck in an angling passport square km of rural Lancashire and Hub to test out the grades before you by day but after the sun sets there’s a scheme operated by the Ribble Rivers North Yorkshire, the AONB provides set off on your venture. -

Proposed Admissions Policy 2021-22

Proposed Admissions Policy 2021-22 11503 Bowland High This is an academy school. Riversmead 11-16 Mixed Comprehensive Grindleton Head: Mrs L. Fielding Clitheroe. BB7 4QS Number on Roll March 2020: 569 01200 441374 Admission Number: 110 Admission number for September 2021: 110 SUMMARY OF POLICY Bowland High is a school serving its local community. This is reflected in its admissions policy. Children will be admitted to the school in the following priority order: a. Looked after children and previously looked after children, then b. Children who have exceptionally strong medical, social or welfare reasons for admission associated with the child and/or family which are directly relevant to the school concerned, then c. Children living in the school's geographical priority area who will have a sibling1 in attendance at the school at the time of transfer, then d. Children living within the school's geographical priority area2,then e. Children of current employees of the school who have had a permanent contract for at least two years prior to the admissions deadline or with immediate effect if the member of staff is recruited to fill a post for which there is a demonstrable skills shortage, then f. Children living outside of the school's geographical priority area who will have a sibling in attendance at the school at the time of transfer, then g. Children living outside of the school's geographical priority area. 1 Sibling includes step children, half brothers and sisters, fostered and adopted children living with the same family at the same address (consideration may be given to applying this criterion to full brothers and sisters who reside at different addresses). -

Ancient Origins of Lordship

THE ANCIENT ORIGINS OF THE LORDSHIP OF BOWLAND Speculation on Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norse and Brythonic roots William Bowland The standard history of the lordship of Bowland begins with Domesday. Roger de Poitou, younger son of one of William the Conqueror’s closest associates, Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury, is recorded in 1086 as tenant-in-chief of the thirteen manors of Bowland: Gretlintone (Grindleton, then caput manor), Slatebourne (Slaidburn), Neutone (Newton), Bradeforde (West Bradford), Widitun (Waddington), Radun (Radholme), Bogeuurde (Barge Ford), Mitune (Great Mitton), Esingtune (Lower Easington), Sotelie (Sawley?), Hamereton (Hammerton), Badresbi (Battersby/Dunnow), Baschelf (Bashall Eaves). William Rufus It was from these holdings that the Forest and Liberty of Bowland emerged sometime after 1087. Further lands were granted to Poitou by William Rufus, either to reward him for his role in defeating the army of Scots king Malcolm III in 1091-2 or possibly as a consequence of the confiscation of lands from Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumbria in 1095. 1 As a result, by the first decade of the twelfth century, the Forest and Liberty of Bowland, along with the adjacent fee of Blackburnshire and holdings in Hornby and Amounderness, had been brought together to form the basis of what became known as the Honor of Clitheroe. Over the next two centuries, the lordship of Bowland followed the same descent as the Honor, ultimately reverting to the Crown in 1399. This account is one familiar to students of Bowland history. However, research into the pattern of land holdings prior to the Norman Conquest is now beginning to uncover origins for the lordship that predate Poitou’s lordship by many centuries. -

Gisburn Forest and Stocks Reservoir Adventure

Discover Bowland Itinerary – No 2 Gisburn Forest and Stocks Reservoir Adventure In the hills above the picturesque village of Slaidburn there’s a paradise for outdoor enthusiasts just waiting to be explored. This pristine upland landscape in Lancashire’s undiscovered rural hinterland is a hidden gem with more in common with the lochs and glens of the Scottish Highlands than the post-industrial mill towns in the south of the county. Walking, trail-running, mountain-biking, fly-fishing and birding are all on the agenda for visitors with a taste for adventure. There’s even an easily accessible trail for outdoor enthusiasts with restricted mobility. Day 1: The Big Adventure Lace up your boots for a big day close to the water or clip into your pedals for a forest The Hodder Valley Show is adventure.The eight-mile Stocks Reservoir an agricultural show which Circular walk climbs into the hills above the changes venue in rotation between reservoir, providing expansive views of the Slaidburn, Newton and Dunsop wider Bowland landscape before descending to Bridge. The event is held the complete a circuit of the entire reservoir. second Saturday of September. Allow at least three hours to complete the Please check website to find out entire circuit on foot. Start from the pay and if it is running in 2021. display car park on the eastern shore of www.hoddervalleyshow.co.uk the reservoir. Detour to the café at Gisburn Forest Hub for welcome refreshments. Families with younger children, or those who are less mobile, might want to try the less demanding Birch Hills Trail starting from the same car park,. -

Ribble Valley Settlement Hierarchy

RIBBLE VALLEY SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY Executive Summary Observations The summary below is derived from the more detailed analyses of the contextual and demographic data set out in Appendix 1 and the local services and facilities data described in Appendix 2. • Clitheroe stands out as the most significant settlement within the Borough, with the best provision of services and facilities • The next two settlements, Longridge and Whalley also stand out from all other settlements in terms of provision across all the various service and facilities categories. While Whalley is smaller than some other settlements, such as Langho and Wilpshire, they have significantly poorer service and facility provision. In Wilpshire’s case this could be due to the services in the area falling into adjacent parts of Blackburn. • Eleven settlements clustered towards the bottom of the hierarchy all scored poorly across nearly all categories. These are: Osbaldeston, Tosside, Copster Green, Pendleton, Sawley, Calderstones, Newton, Wiswell, Rimington, Worston and Holden. Only in terms of community facilities did a few of this group, Pendleton, Newton and Rimington, have good or reasonable provision. This leaves 21 remaining settlements within the hierarchy with a spectrum of provision between these two extremes. There are no significant “step changes” within this group, however those towards the top of this group, scoring 20 and above points were considered the initially most likely to possibly act as more local centres. It could be argued that this 20 point limit is somewhat arbitrary however. • This group contains: Langho, Mellor, Chatburn, Ribchester, Waddington, Dunsop Bridge and Sabden. Most of this group, perhaps unsurpringly, have relatively large populations of over 1000, with only Waddington and Dunsop Bridge being smaller. -

Parish Council Liaison Minutes

Minutes of Parish Councils’ Liaison Committee Meeting Date: Thursday, 26 September 2019, starting at 6.30pm Present: (Chairman) Councillors: A Brown D Peat B Hilton G Scott B Holden R Sherras S Hore N Walsh G Mirfin Parish Representatives: R Wilkinson Aighton Bailey & Chaigley K Barker Balderstone J Brown Barrow K Swingewood Billington & Langho T Austin Billington & Langho L Edge Clayton-le-Dale B Phillips Dinckley J Hargreaves Dutton P Entwistle Grindleton M Gee Hothersall B Murtagh Mellor N Marsden Mellor S Rosthorn Newsholme & Paythorne M Beattie Newton-in-Bowland P Ainsworth Osbaldeston P Young Ramsgreave C Pollard Read M Hacking Read D Groves Ribchester R Whittaker Rimington & Middop T Perry Rimington & Middop A Haworth Sabden P Vickers Sabden G Henderson Salesbury J Westwell Salesbury G Meloy Simonstone R Hirst Simonstone H Parker Waddington J Hilton Waddington A Bristol West Bradford J Brown Whalley J Bremner Wilpshire M Robinson Wiswell S Stanley Wiswell In attendance: Chief Executive and Head of Regeneration and Housing. 80 280 APPOINTMENT OF CHAIRMAN FOR 2019/2020 RESOLVED: That Parish Councillor Martin Highton be appointed as Chairman for this Committee for 2019/2020. 281 APOLOGIES Apologies for absence from the meeting were submitted on behalf of Borough Councillors D Berryman, B Buller, J Schumann and R Thompson and from the following Parish Representatives: E Twist Bolton-by-Bowland, Gisburn Forest & Sawley H Fortune Bolton-by-Bowland, Gisburn Forest & Sawley B Green Chipping A Schofield Clayton-le-Dale R Assheton Downham P Rigby LCC Parish Champion 282 MINUTES The minutes of the meeting held on 20 June 2019 were approved as a correct record and signed by the Chairman. -

Conservation Area Appraisals

Ribble Valley Borough Council - Newton Conservation Area Appraisal 1 _____________________________________________________________________ NEWTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL This document has been written and produced by The Conservation Studio, 1 Querns Lane, Cirencester, Gloucestershire GL7 1RL Final revision 25.10.05/ photos added 18.12.06 The Conservation Studio 2005 Ribble Valley Borough Council - Newton Conservation Area Appraisal 2 _____________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Introduction Purpose of the appraisal Summary of special interest The planning policy context Local planning policy Location and setting Location and context General character and plan form Landscape setting Topography, geology, relationship of the conservation area to its surroundings Historic development and archaeology Origins and historic development Spatial analysis Key views and vistas The character of spaces within the area Definition of the special interest of the conservation area Activities/uses Plan form and building types Architectural qualities Listed buildings Buildings of Townscape Merit Local details Green spaces, trees and other natural elements Issues Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities Threats Recommendations Conservation Area boundary review Article 4 Direction Monitoring and review Bibliography The Conservation Studio 2005 Ribble Valley Borough Council - Newton Conservation Area Appraisal 3 _____________________________________________________________________ NEWTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Introduction Purpose of the appraisal This appraisal seeks to record and analyse the various features that give the Newton Conservation Area its special architectural and historic interest. The area’s buildings and spaces are noted and described, and marked on the Townscape Appraisal Map along with significant trees, surviving historic paving, and important views into and out of the conservation area. There is a presumption that all of these features should be “preserved or enhanced”, as required by the legislation. -

Bowland Rambler – Brungerley Bridge to Grindleton Bridge About This Walk Sustainable Tourism Countryside / Moorland Code Safety

Bowland Rambler – Walk Description Areas of Brungerley Park are fully brings you out on the West Brungerley Bridge to Grindleton Bridge accessible to wheelchair users. Bradford road. 1 Walk through Brungerley Park along 7 Turn left and just before the bridge Start Point Distance/Time Terrain OS Explorer the lower riverside path – take the steps on your right, down Brungerley 5 Miles Roads, tracks and waymarked ‘Ribble Way’. to the river. Walk along the river fields. Gates and until you come to a posted ‘No Park OL41 2 At the Crosshill Nature Reserve 1 Hr some stiles. ‘ Forest of Bowland take the left fork, through a kissing Right of Way’ sign. SD 743 432 40 Mins and Ribblesdale’ gate and follow the riverbank to 8 Turn right and keeping the West Bradford Bridge. hedgerow to your left go through two kissing gates. N 3 On reaching the Bridge, exit to the main road and cross over to the lay- 9 From here take a bearing left that by opposite. Take the path to the will guide you through two fields to river via the kissing gate. Follow the a disused quarry. Beyond the quarry riverbank past a pump house, then are open fields. over a small limestone outcrop until 6 10 Take a diagonal route to a farm track. you reach the second bench. Cross this via two stiles. Take a 7 5 4 Bear away from the river and follow bearing left of the telegraph pole 4 the elevated path to a metal kissing until you reach a farmyard. -

Gisburn Forest and Stocks

Dob Dale Enjoy your your Enjoy experience. full the reservoir for Path Circular Try Stocks the apicnic. for place viewing, agreat and birdlife Fantastic you. for is just Reservoir Stocks Then wildlife? Love From Stocks Reservoir... from. start trails walking the where Reservoir Stocks is alink to path there walk agood want Skillsthe If you Loop. Try practice? some Need Hub. Gisburn If thing, biking is your all trails start from Hub... Gisburn From outdoors. great the experience and relax to place a wilder is &Stocks Gisburn Forest biking, or walking Whether a n dstocks Gisb ur nforest Welcome 24 Support Gisburn Forest & Stocks with a forestry.gov.uk/pass reservoir. forest and after look the discounts. also It us helps and savings parking, £30 A Discovery Pass is only Fair Hill H u lly Gully for a whole year of of year awhole for biking 23 Whelp Stone Crag Join onlineJoin at 22 n o rth Bigfoot slab Waymarkers Whelp Stone Crag MAP Scale 21 0 0.5km 1km Herd Hill 0 0.25 miles 0.5 miles 25 Discovery Pass Public Biking time here... bridleway trail Bottom Heights Public footpath to Geldard Laithe Simons Swamp Key to map Bottoms Hesbert Hall Heights 19 6 Location markers Trail start points 26 Log Ride Leap of Faith Sheep Hill 18 Boardwalk Swoopy Trail sections 17 Mobile reception Heath Farm 2 Home Baked Hope Line Gravel road Admission Visitor [email protected] formats. alternative make publications available in to all requests will consider We forestry.gov.uk/gisburn Gisburn Forest &Stocks Gisburn Forest dawn to dusk all dusk to dawn year operates in Gisburnoperates available. -

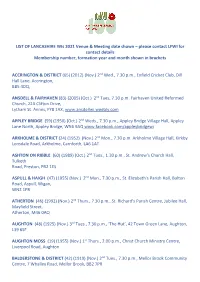

Lancashire Federation of Women's Institutes

LIST OF LANCASHIRE WIs 2021 Venue & Meeting date shown – please contact LFWI for contact details Membership number, formation year and month shown in brackets ACCRINGTON & DISTRICT (65) (2012) (Nov.) 2nd Wed., 7.30 p.m., Enfield Cricket Club, Dill Hall Lane, Accrington, BB5 4DQ, ANSDELL & FAIRHAVEN (83) (2005) (Oct.) 2nd Tues, 7.30 p.m. Fairhaven United Reformed Church, 22A Clifton Drive, Lytham St. Annes, FY8 1AX, www.ansdellwi.weebly.com APPLEY BRIDGE (59) (1950) (Oct.) 2nd Weds., 7.30 p.m., Appley Bridge Village Hall, Appley Lane North, Appley Bridge, WN6 9AQ www.facebook.com/appleybridgewi ARKHOLME & DISTRICT (24) (1952) (Nov.) 2nd Mon., 7.30 p.m. Arkholme Village Hall, Kirkby Lonsdale Road, Arkholme, Carnforth, LA6 1AT ASHTON ON RIBBLE (60) (1989) (Oct.) 2nd Tues., 1.30 p.m., St. Andrew’s Church Hall, Tulketh Road, Preston, PR2 1ES ASPULL & HAIGH (47) (1955) (Nov.) 2nd Mon., 7.30 p.m., St. Elizabeth's Parish Hall, Bolton Road, Aspull, Wigan, WN2 1PR ATHERTON (46) (1992) (Nov.) 2nd Thurs., 7.30 p.m., St. Richard’s Parish Centre, Jubilee Hall, Mayfield Street, Atherton, M46 0AQ AUGHTON (48) (1925) (Nov.) 3rd Tues., 7.30 p.m., ‘The Hut’, 42 Town Green Lane, Aughton, L39 6SF AUGHTON MOSS (19) (1955) (Nov.) 1st Thurs., 2.00 p.m., Christ Church Ministry Centre, Liverpool Road, Aughton BALDERSTONE & DISTRICT (42) (1919) (Nov.) 2nd Tues., 7.30 p.m., Mellor Brook Community Centre, 7 Whalley Road, Mellor Brook, BB2 7PR BANKS (51) (1952) (Nov.) 1st Thurs., 7.30 p.m., Meols Court Lounge, Schwartzman Drive, Banks, Southport, PR9 8BG BARE & DISTRICT (67) (2006) (Sept.) 3rd Thurs., 7.30 p.m., St. -

Forest of Bowland AONB Landscape Character Assessment 2009

Craven Local Plan FOREST OF BOWLAND Evidence Base Compiled November 2019 Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Part I: Forest of Bowland AONB Landscape Character Assessment 2009 ...................................... 4 Part II: Forest of Bowland AONB Management Plan 2014-2019 February 2014 .......................... 351 Part III: Forest of Bowland AONB Obtrusive Lighting Position Statement ..................................... 441 Part IV: Forest of Bowland AONB Renewable Energy Position Statement April 2011 .................. 444 2 of 453 Introduction This document is a compilation of all Forest of Bowland (FoB) evidence underpinning the Craven Local Plan. The following table describes the document’s constituent parts. Title Date Comments FoB AONB Landscape Character September The assessment provides a framework Assessment 2009 for understanding the character and (Part I) future management needs of the AONB landscapes, and an evidence base against which proposals for change can be judged in an objective and transparent manner. FoB AONB Management Plan 2014-2019 February 2014 The management plan provides a (Part II) strategic context within which problems and opportunities arising from development pressures can be addressed and guided, in a way that safeguards the nationally important landscape of the AONB. In fulfilling its duties, Craven District Council should have regard to the Management Plan as a material planning consideration. FoB AONB Obtrusive Lighting Position N/A The statement provides guidance to all Statement AONB planning authorities and will assist (Part III) in the determination of planning applications for any development which may include exterior lighting. FoB AONB Renewable Energy Position April 2011 The statement provides guidance on the Statement siting of renewable energy developments, (Part IV) both within and adjacent to the AONB boundary.