Best Management Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINNESOTA MUSTELIDS Young

By Blane Klemek MINNESOTA MUSTELIDS Young Naturalists the Slinky,Stinky Weasel family ave you ever heard anyone call somebody a weasel? If you have, then you might think Hthat being called a weasel is bad. But weasels are good hunters, and they are cunning, curious, strong, and fierce. Weasels and their relatives are mammals. They belong to the order Carnivora (meat eaters) and the family Mustelidae, also known as the weasel family or mustelids. Mustela means weasel in Latin. With 65 species, mustelids are the largest family of carnivores in the world. Eight mustelid species currently make their homes in Minnesota: short-tailed weasel, long-tailed weasel, least weasel, mink, American marten, OTTERS BY DANIEL J. COX fisher, river otter, and American badger. Minnesota Conservation Volunteer May–June 2003 n e MARY CLAY, DEMBINSKY t PHOTO ASSOCIATES r mammals a WEASELS flexible m Here are two TOM AND PAT LEESON specialized mustelid feet. b One is for climb- ou can recognize a ing and the other for hort-tailed weasels (Mustela erminea), long- The long-tailed weasel d most mustelids g digging. Can you tell tailed weasels (M. frenata), and least weasels eats the most varied e food of all weasels. It by their tubelike r which is which? (M. nivalis) live throughout Minnesota. In also lives in the widest Ybodies and their short Stheir northern range, including Minnesota, weasels variety of habitats and legs. Some, such as badgers, hunting. Otters and minks turn white in winter. In autumn, white hairs begin climates across North are heavy and chunky. Some, are excellent swimmers that hunt to replace their brown summer coat. -

2021 Fur Harvester Digest 3 SEASON DATES and BAG LIMITS

2021 Michigan Fur Harvester Digest RAP (Report All Poaching): Call or Text (800) 292-7800 Michigan.gov/Trapping Table of Contents Furbearer Management ...................................................................3 Season Dates and Bag Limits ..........................................................4 License Types and Fees ....................................................................6 License Types and Fees by Age .......................................................6 Purchasing a License .......................................................................6 Apprentice & Youth Hunting .............................................................9 Fur Harvester License .....................................................................10 Kill Tags, Registration, and Incidental Catch .................................11 When and Where to Hunt/Trap ...................................................... 14 Hunting Hours and Zone Boundaries .............................................14 Hunting and Trapping on Public Land ............................................18 Safety Zones, Right-of-Ways, Waterways .......................................20 Hunting and Trapping on Private Land ...........................................20 Equipment and Fur Harvester Rules ............................................. 21 Use of Bait When Hunting and Trapping ........................................21 Hunting with Dogs ...........................................................................21 Equipment Regulations ...................................................................22 -

Mink: Wildlife Notebook Series

Mink The American mink (Neovison vison) and other fur bearing animals attracted trappers, traders, and settlers to Alaska from around the world. Some of the most valuable furbearers belong to the Mustelidae or weasel family, which includes the American mink. Other members of this family in Alaska include weasels, martens, wolverines, river otters, and sea otters. Mink are found in every part of the state with the exceptions of Kodiak Island, Aleutian Islands, the offshore islands of the Bering Sea, and most of the Arctic Slope. General description: A mink's fur is in prime condition when guard hairs are thickest. Mink are then a chocolate brown with some irregular white patches on the chin, throat, and belly. White patches are usually larger on females and often occur on the abdomen in the area of the mammary glands. Several albino mink have been reported from Alaska. Underfur is usually thick and wavy, not longer than an inch. It is dark gray to light brown in color with some suggestion of light and dark bands. The tail is one third to one fourth of the body length with slightly longer guard hairs than the body. As an adaptation to their aquatic lifestyle, their feet have semiwebbed toes and oily guard hairs tend to waterproof the animal. Adult males range in total length from 19 to 29 inches (48-74 cm). They may weigh from three to almost five pounds (1.4-2.3 kg). Females are somewhat smaller than males. Their movements are rapid and erratic as if they are always ready to either flee or pounce on an unwary victim. -

FURS: GENERAL INFORMATION by Elizabeth R

2 Revised U. So DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Letter March 10 National Bureau of Standards Circular 1964 Washington, D. C. 20234 LCSSS FURS: GENERAL INFORMATION by Elizabeth R. Hosterman CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 2 2. KINDS OF FURS: CHARACTERISTICS AND GEOGRAPHICAL 3 SOURCES 2.1 Rodent Family 4 (a) Water rodents 4 (b) Land rodents 4 2.2 Weasel Family 5 2.3 Cat Family 7 2.4 Dog Family S (a) Foxes 3 (b) Wolves a 2.5 Hoofed Animals 9 2.6 Bear-Raccoon Group 10 2.7 Miscellaneous 10 3. FUR MANUFACTURING 10 3.1 Curing and Dressing 10 3.2 Drying and Staking 11 3.3 Dyeing 13 4. SELECTION OF FURS BY CONSUMERS 15 4.1 Cost 15 4 . Use and Durability 16 4.3 Where To Buy 16 4.4 Labels 17 4.5 Workmanship IS 4.6 Quality 19 4.7 Genuine or Simulated 19 4.3 Fit, Style, and Color 19 5. CARE OF FURS 20 5.1 Home and Wearing Care 20 5.2 Storage Care 21 5.3 Cleaning of Furs 21 6. GLOSSARY OF TERMS 22 7 » BIBLIOGRAPHY 23 2 1. INTRODUCTION Both leather dressing and fur dressing have an origin which may be regarded as identical and which date back to a hazy period of antiquity. Ancient man killed animals in order to obtain food. The animals also furnished a skin which, after undergoing certain treatments, could be used as a covering for the body. Man had to, and did, find some means of preventing decay in a more or less permanent fashion. -

The Slinky, Stinky Weasel Family

Minnesota Conservation Volunteer Young Naturalists Prepared by Jack “The Slinky, Stinky Weasel Family,” Judkins, Bemidji Multidisciplinary Classroom Activities Area Schools, Teachers guide for the Young Naturalists article “The Slinky, Stinky Weasel Family,” Bemidji, Minnesota by Blane Klemek. Published in the May–June 2003 Volunteer, or visit www.dnr.mn.us/ young_naturalists/weasels. Young Naturalists teachers guides are provided free of charge to classroom teachers, parents, and students. This guide contains a brief summary of the article, suggested independent reading levels, word count, materials list, estimates of preparation and instructional time, academic standards applications, preview strategies and study questions overview, adaptations for special needs students, assessment options, extension activities, Web resources (including related Conservation Volunteer articles), copy-ready study questions with answer key, and a copy-ready vocabulary sheet and vocabulary study cards. There is also a practice quiz (with answer key) in Minnesota Comprehensive Assessments format. Materials may be reproduced and/or modified a to suit user needs. Users are encouraged to provide feedback through an online survey at www.mdnr.gov/education/teachers/ activities/ynstudyguides/survey.html. Summary Weasels comprise the largest family of carnivores on earth. Eight species inhabit Minnesota. Following a general description of weasels’ physical characteristics and habits, the author provides a detailed look at each species, including short-tailed weasels, -

Fatal Hemorrhagic-Necrotizing Pancreatitis Associated with Pancreatic and Hepatic Lipidosis in an Obese Asian Palm Civet

Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2014; 4(Suppl 1): S62-S65 S62 Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine journal homepage: www.apjtb.com Document heading doi:10.12980/APJTB.4.2014C915 2014 by the Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. All rights reserved. 襃 Fatal hemorrhagic-necrotizing pancreatitis associated with pancreatic and hepatic lipidosis in an obese Asian palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus) 1 2 2 1 2 Bongiovanni Laura *, Di Girolamo Nicola , Montani Alessandro , Della Salda Leonardo , Selleri Paolo 1Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Teramo, Teramo, Italy 2Clinica per Animali Esotici, Centro Veterinario Specialistico, Via Sandro Giovannini 53, Rome, Italy PEER REVIEW ABSTRACT Peer reviewer Paradoxurus hermaphroditus Asian palm civets ( ), or toddy cats, belong to the family Viverridae. Dr. Changbo Ou, Department of Little is known about the pathology of these animals and few articles have been published, Preventive Veterinary Medicine, mainly concerning their important role as wild reservoir hosts for severe infectious diseases of College of Animal Science, Henan domestic animals and human beings. A 4-year-old, female Asian palm civet was found dead Institute of Science and Technology, by the owner. At necropsy, large amount of adipose tissue was found in the subcutis and in the Xinxiang 453000, Henan Province, peritoneal cavity. Most of the pancreas appeared red, translucent. Hepatomegaly, discoloration China. of the liver were evident, with multifocal areas of degeneration, characterized by white nodular E-mail: [email protected] lesions. Histologically, the pancreas showed severe interstitial and perilobular necrosis and Comments extensive haemorrhages, with separation of the interstitium, mild reactive inflammation at the periphery of the pancreatic lobules. -

Mitochondrial DNA and Palaeontological Evidence for the Origins of Endangered European Mink, Mustela Lutreola

Animal Conservation (2000) 4, 345–355 © 2000 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom Mitochondrial DNA and palaeontological evidence for the origins of endangered European mink, Mustela lutreola Angus Davison1,2,†, Huw I. Griffiths3, Rachael C. Brookes1,2, Tiit Maran4, David W. Macdonald5, Vadim E. Sidorovich6, Andrew C. Kitchener7, Iñaki Irizar8, Idoia Villate8, Jorge González-Esteban8, Juan Carlos Ceña9, Alfonso Ceña9, Ivan Moya9 and Santiago Palazón Miñano10 1 Vincent Wildlife Trust, 10 Lovat Lane, London EC3R 8DT, UK 2 Institute of Genetics, Q.M.C., University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG7 2UH, UK 3 Department of Geography, University of Hull, Kingston-upon-Hull HU6 7RX, UK 4 E. M. C. C., Tallinn Zoo, 1 Paldiski Road 145, Tallinn EE0035, Estonia 5 WildCRU, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK 6 Institute of Zoology, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, Skoriny str. 27, Minsk – 220072, Belarus 7 National Museums of Scotland, Chambers St., Edinburgh EH1 1JF, UK 8 Departamento de Vertebrados, Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi, Alto de Zorroaga, E – 20014 Donostia – San Sebastián, Spain 9 C/Estambrera 13, 3º-B, Logroño, Spain 10 Departament de Biologia Animal (Vertebrats), Universitat de Barcelona, Avda Diagonal 645, 08028 Barcelona, Spain (Received 13 January 2000; accepted 6 July 2000) Abstract The European mink Mustela lutreola is one of Europe’s most endangered carnivores, with few vul- nerable populations remaining. Surprisingly, a recent phylogeny placed a single mink specimen within the polecat (M. putorius, M. eversmannii) group, suggesting a recent speciation and/or the effects of hybridization. The analysis has now been extended to a further 51 mink and polecats. -

Fifty Years of Research on European Mink Mustela Lutreola L., 1761 Genetics: Where Are We Now in Studies on One of the Most Endangered Mammals?

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Fifty Years of Research on European Mink Mustela lutreola L., 1761 Genetics: Where Are We Now in Studies on One of the Most Endangered Mammals? Jakub Skorupski 1,2 1 Institute of Marine and Environmental Sciences, University of Szczecin, Adama Mickiewicza 16 St., 70-383 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected]; Tel.: +48-914-441-685 2 Polish Society for Conservation Genetics LUTREOLA, Maciejkowa 21 St., 71-784 Szczecin, Poland Received: 2 October 2020; Accepted: 6 November 2020; Published: 11 November 2020 Abstract: The purpose of this review is to present the current state of knowledge about the genetics of European mink Mustela lutreola L., 1761, which is one of the most endangered mammalian species in the world. This article provides a comprehensive description of the studies undertaken over the last 50 years in terms of cytogenetics, molecular genetics, genomics (including mitogenomics), population genetics of wild populations and captive stocks, phylogenetics, phylogeography, and applied genetics (including identification by genetic methods, molecular ecology, and conservation genetics). An extensive and up-to-date review and critical analysis of the available specialist literature on the topic is provided, with special reference to conservation genetics. Unresolved issues are also described, such as the standard karyotype, systematic position, and whole-genome sequencing, and hotly debated issues are addressed, like the origin of the Southwestern population of the European mink and management approaches of the most distinct populations of the species. Finally, the most urgent directions of future research, based on the research questions arising from completed studies and the implementation of conservation measures to save and restore M. -

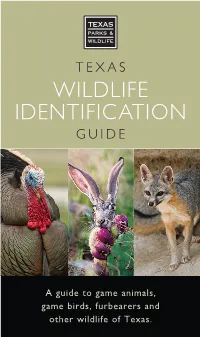

Texas Wildlife Identification Guide

TEXAS WILDLIFE IDENTIFICATION GUIDE A guide to game animals, game birds, furbearers and other wildlife of Texas. INTRODUCTION Texas game animals, game birds, furbearers and other wildlife are important for many reasons. They provide countless hours of viewing and recreational opportunities. They benefit the Texas economy through hunting and “nature tourism” such as birdwatching. Commercial businesses that provide birdseed, dry corn and native landscaping may be devoted solely to attracting many of the animals found in this book. Local hunting and trapping economies, guiding operations and hunting leases have prospered because of the abun- dance of these animals in Texas. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department benefits because of hunting license sales, but it uses these funds to research, manage and protect all wildlife populations – not just game animals. Game animals provide humans with cultural, social, aesthetic and spiritual pleasures found in wildlife art, taxidermy and historical artifacts. Conservation organiza- tions dedicated to individual species such as quail, turkey and deer, have funded thousands of wildlife projects throughout North America, demonstrating the mystique game animals have on people. Animals referenced in this pocket guide exist because their habitat exists in Texas. Habitat is food, cover, water and space, all suitably arranged. They are part of a vast food chain or web that includes thousands more species of wildlife such as the insects, non-game animals, fish and i rare/endangered species. Active management of wild landscapes is the primary means to continue having abundant populations of wildlife in Texas. Preservation of rare and endangered habitat is one way of saving some species of wildlife such as the migratory whooping crane that makes Texas its home in the winter. -

Vaccine Protocols for Weasels and Mink

Vaccine Protocols for Weasels and Mink These are recommendations from a veterinarian experienced in ferret and domestic mink veterinary care, and can be applied to wild mink and weasels with precautions. Keep in mind the metabolism of wild mink is faster than the domestic mink or ferrets, and the weasel metabolism is about 2-4 times faster than the wild mink. Only use the ferret-specific vac, or the puppy vac "Nobivac DPV". That said Novibac has less reactions apparently but there is the slight possibility they could get actual distemper from them (I think this is true with the ferret specific one too, although I could be wrong). I think the benefit outweighs the risk though. Availability of the ferret vac can be problematic. Currently a 10 pack of the ferret-specific vac can be purchased for about $180. Do NOT pre-medicate with benedryl. This can mask the symptoms of a reaction, cause a delayed reaction, and some animals may possibly even react to the benedryl. If there's a reaction you want to be able to see it immediately and treat it. A reaction being masked is dangerous- you need to be able to see if there is ANY reaction, so that you can never administer that vac again. Most vets are using Dex-SP at 2 mg/kg IM 30 minutes prior to vaccination in ferrets. It’s a steroid. Stay at the vet for at least 30 min after the shot. Make sure your vet is aware of the risks and ready to reverse a reaction, should one happen. -

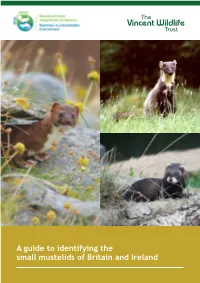

A Guide to Identifying the Small Mustelids of Britain and Ireland the Small Mustelids Or Weasel Family

A guide to identifying the small mustelids of Britain and Ireland The small mustelids or weasel family Order: Carnivora Family: Mustelidae The small mustelids are characterised by their long thin body shape, which enables them to follow their prey down small tunnels and burrows. However, because of their similar body shape they can be difficult to distinguish from each other, especially when, as is usually the case, they are seen only briefly and in poor light! Otter Pine Marten Mink Photograph by Clive Craik Polecat For the purposes of identification they can be separated into two groups Stoat based on size: Weasel 1. Weasel and stoat 2. Pine marten, polecat, The otter, one of our larger polecat-ferret and mink mustelids, is shown here for size comparison only. Cover photographs: Irish stoat by Carrie Crowley, Pine marten by Bill Cuthbert, Polecat by Jane Parsons 1. Weasel (Mustela nivalis) and stoat (Mustela erminea) (head and body less than 30cm) Weasels and stoats are generally much smaller than the rest of the mustelids. The other distinguishing feature is the sharp contrast between the reddish-brown coat colour on their back and sides and the creamy white fur on the throat, chest and belly. The weasel The weasel is the smallest of the small mustelids and the smallest of all the carnivores. It has short legs and a slender body (17-24cm). The fur is chestnut brown on the back and head with a creamy white belly, and the division between brown and cream is irregular and spotted. This irregular pattern is different for each animal so can be used to identify individuals. -

Furbearer Trapping and Hunting

Furbearer Trapping and Hunting Credentials (does not include vendor fees) Price How to apply for or purchase License/Permit/Stamps Resident Non-Resident Lottery Online Vendors Phone Paper Application Specifications Trapping $10.00 X X X First-time trappers born on or after Jan. 1, 1998 are required to complete a trapper education course before purchasing a license. Residents with at least 39.5 acres do not need a license to trap. FURBEARER TRAPPING AND HUNTING Youth Hunting and Trapping $7.00 X X X Any hunter/trapper under 18 years of age may purchase this license. Hunters/trappers with this license must be supervised by an adult who is 21 years of age or older and has the appropriate Illinois hunting or trapping license. The youth hunter shall not hunt or trap or carry a hunting device, unless the youth is accompanied by and under close personal supervision of that adult. Trapping $175.00 X X X Reciprocity means your state of residence allows (with state reciprocity) Illinois residents to trap. Trapping $250.00 X X X See reciprocity specification above. (without state reciprocity) Base Hunting License Variable Variable X X X X See Statewide Regulations section for license types. State Habitat Stamp $5.00 $5.00 X X X Species-specific Permits Otter Registration Permit $5.00 $5.00 X X X Purchase within 48 hours after otter harvest. Bobcat Hunting & $5.00 $5.00 X X See lottery section for details. Trapping Lottery Application Bobcat Registration Permit $5.00 $5.00 X Purchase within 48 hours after bobcat harvest.