Clocks and Empire: an Indian Case Study”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Horizon Tours

New Horizon Tours Presents INTOXICATING, INCREDIBLE INDIA MARCH 14 -MARCH 26, 2020 (LAX) Mar. 14, SAT: PARTICIPANTS from Los Angeles (LAX) board on Emirates air at 4.35PM Mar. 15, SUN: LAX PARTICIPANTS ARRIVE IN DUBAI AND CONNECT FLIGHT TO MUMBAI / Washington (IAD) participants depart at 11.10 AM Mar. 16, MON: ARRIVE MUMBAI Different times- LAX passengers arrive at 2.15AM (immediate occupancy of rooms- rooms reserved from Mar. 15). IAD passengers arrive at 2.00 PM- separate arrival transfers for each in Mumbai. Arrive in Mumbai, a cluster of seven islands derives its name from Mumba devi, the patron goddess of Koli fisher folk, the oldest habitants. Meeting assistance and transfer to Hotel. Rest of the day is free. Evening welcome dinner at roof top restaurant at Hotel near airport. HOTEL.OBEROI TRIDENT (Breakfast & Dinner for LAX passengers, Dinner only for IAD participants). Mar. 17, TUE: MUMBAI - CITY TOUR – BL Breakfast at Hotel. This morning embark on city tour of Mumbai visiting the British built Gateway of India, Bombay's landmark constructed in 1927 to commemorate Emperor George V's visit, the first State, ever to see India by a reigning monarch. Followed by a drive through the city to see the unique architecture, Mumbai University, Victoria Terminus, Marine Drive, Chowpatty Beach. Next stop at Hanging Gardens (now known as Sir K.P. Mehta Gardens), where the old English art of topiary is practiced. Continue to the Dhobi Ghat, an open-air laundry where washmen physically clean and iron hundreds of items of clothing, delivering them the next day. -

CRAMPED for ROOM Mumbai’S Land Woes

CRAMPED FOR ROOM Mumbai’s land woes A PICTURE OF CONGESTION I n T h i s I s s u e The Brabourne Stadium, and in the background the Ambassador About a City Hotel, seen from atop the Hilton 2 Towers at Nariman Point. The story of Mumbai, its journey from seven sparsely inhabited islands to a thriving urban metropolis home to 14 million people, traced over a thousand years. Land Reclamation – Modes & Methods 12 A description of the various reclamation techniques COVER PAGE currently in use. Land Mafia In the absence of open maidans 16 in which to play, gully cricket Why land in Mumbai is more expensive than anywhere SUMAN SAURABH seems to have become Mumbai’s in the world. favourite sport. The Way Out 20 Where Mumbai is headed, a pointer to the future. PHOTOGRAPHS BY ARTICLES AND DESIGN BY AKSHAY VIJ THE GATEWAY OF INDIA, AND IN THE BACKGROUND BOMBAY PORT. About a City THE STORY OF MUMBAI Seven islands. Septuplets - seven unborn babies, waddling in a womb. A womb that we know more ordinarily as the Arabian Sea. Tied by a thin vestige of earth and rock – an umbilical cord of sorts – to the motherland. A kind mother. A cruel mother. A mother that has indulged as much as it has denied. A mother that has typically left the identity of the father in doubt. Like a whore. To speak of fathers who have fought for the right to sire: with each new pretender has come a new name. The babies have juggled many monikers, reflected in the schizophrenia the city seems to suffer from. -

Bombay Dreams

Bombay Dreams Bombay Dreams 4 days | Starts/Ends: Mumbai PRIVATE TOUR: Formally known • All relevant transfer and transportation than any place in the world and of course the as Bombay, exhilarating and in private modern Chauffeur driven air- setting for the hit film ‘Slum Dog Millionaire’. charismatic Mumbai is the most conditioned vehicles populated city in the world, India’s What's Not Included The main draw of Mumbai, like much of India, financial powerhouse, and the remains its contradictions. Within minutes (or • International flights and visa a few miles) you can be awestruck by the home of Bollywood and the setting • Tipping - An entirely personal gesture palatial houses on Malabar Hill and then of the hit film ‘Slum Dog Millionaire’. depressed by the makeshift shacks and ITINERARY the children in the city’s poverty-stricken HIGHLIGHTS AND INCLUSIONS neighbourhoods. Day 1 : City of dreams Overnight - Mumbai Trip Highlights Arrive Mumbai. If arriving to Mumbai from a domestic flight you will arrive to Terminal 2. Day 2 : Elephanta Caves & • Elephanta Caves - Rock cut temples There are arrival gates A, B and C. Please exit • Dhobi Talao ghats - Mass clothes washing city tour via Gate B and turn right. Our representative site by the waters edge Enjoy a cruise to the Elephanta Caves this will be waiting here on the right for you. From • Crawford Market - Colourful stalls for a morning. The island of Elephanta is about 10 this meeting point you should also be able to spot of bargaining kms from Mumbai. The 4 rock-cut temples see a Starbucks Coffee Shop to the east. -

Mumbai Local Sightseeing Tours

Mumbai Local Sightseeing Tours HALF DAY MUMBAI CITY TOUR Visit Gateway of India, Mumbai's principle landmark. This arch of yellow basalt was erected on the waterfront in 1924 to commemorate King George V's visit to Mumbai in 1911. Drive pass the Secretariat of Maharashtra Government and along the Marine Drive which is fondly known as the 'Queen's Necklace'. Visit Jain temple and Hanging Gardens, which offers a splendid view of the city, Chowpatty, Kamala Nehru Park and also visit Mani Bhavan, where Mahatma Gandhi stayed during his visits to Mumbai. Drive pass Haji Ali Mosque, a shrine in honor of a Muslim Saint on an island 500 m. out at sea and linked by a causeway to the mainland. Stop at the 'Dhobi Ghat' where Mumbai's 'dirties' are scrubbed, bashed, dyed and hung out to dry. Watch the local train passing close by on which the city commuters 'hang out like laundry' ‐ a nice photography stop. Continue to the colorful Crawford market and to the Flora fountain in the large bustling square, in the heart of the city. Optional visit to Prince of Wales museum (closed on Mondays). TOUR COST : INR 1575 Per Person The tour cost includes : • Tour in Ac Medium Car • Services of a local English‐speaking Guide during the tour • Government service tax The tour cost does not include: • Entry fees at any of the monuments listed in the tour. The same would be on direct payment basis. • Any expenses of personal nature Note: The above tour is based on minimum 2 persons traveling together in a car. -

Mumbai's Urban Form and Security in the Vernacular

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs Title: ‘These streets are ours’: Mumbai’s urban form and security in the vernacular Citation: Gupte, J. (2017) '‘These streets are ours’: Mumbai’s urban form and security in the vernacular', Peacebuilding 5.2: 203-217 https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2016.1277022 Official url: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21647259.2016.1277022 More details/abstract: This article contributes to the growing literature on the spatial dynamics of urban violence in the developing world. It highlights the dialectic between urban form, violence and security provision as vernacular in nature, shaped by hyperlocal processes and actors. And yet, this dialectic is dominated by state and military-centred terminology, and continually underpinned by the state’s imposition of order to constitute the city as a site for legitimate control. This materialises as the often arbitrary recognition of one area as ‘at the margins’, and not another, as the recognition of one group of people as ‘slum dwellers’ or illegal residents, and not others, or as the recognition of some individuals as criminal, and not others. Using detailed case study material from a group of inner-city neighbourhoods in Mumbai, India, the article suggests that urban form in its physical, political and historical characterisations not only influences how vigilante protection operates, but also interacts in a non-benign manner with the mechanics by which the state endeavours to control violence. As such, it shapes who is vulnerable to violence, how vulnerable they are, and why. -

Mumbai on the Move Approximately 4¼ Hours $$ Enjoyed

A Day in the Life: Mumbai on the Move Approximately 4¼ Hours $$ Enjoyed it? 4 out of 5 Value 3 out of 5 1 out of 1(100%)reviewers would recommend this product to a friend. Read 1 review | Write a review Experience the real, everyday Mumbai, including the highlights of this fascinating city, with its Western monuments and Eastern sensibilities. Begin at the beginning, with the Gateway of India. This is the city’s most famous landmark—an Indo-Saracenic archway built in 1911 to commemorate the visit of King George V and Queen Mary. It was originally conceived as an entry point for passengers arriving on P&O steamers from England; today, it is remembered more often as the place from which the British staged their final departure. You will stop here for photographs. Continue your excursion with an orientation drive through Mumbai passing prominent landmarks such as Flora Fountain, the university and Victoria Terminus. The latter is a most remarkable railway station, inspired by St Pancras Station in London. It was built during Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee year and is an extraordinary conglomeration of domes, spires, Corinthian columns and minarets in a style described by journalist James Cameron as Victorian- Gothic-Saracenic-Italianate-Oriental-St Pancras-Baroque. The first train in India left from this station in 1853; today, half-a-million commuters use the station every day. At theMani Bhawan Gandhi Museum you’ll visit the site that was Mahatma Gandhi’s Bombay base between 1917 and 1934. A series of tiny dioramas tell Gandhi’s life story. -

Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai

Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR PREPARATION OF FEASIBILITY REPORT, DPR PREPARATION, REPORT ON ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES AND OBTAINING MOEF CLEARANCE AND BID PROCESS MANAGMENT FOR MUMBAI COASTAL ROAD PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT August 2016 STUP Consultants Pvt. Ltd. Ernst& Young Pvt. Ltd Plot 22-A, Sector 19C, 8th floor, Golf View Corporate Tower Palm Beach Marg, Vashi, B, Sector 42, Sector Road Navi Mumbai 400 705 , Gurgaon - 122002, Haryana CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR PREPARATION OF STUP Consultants P. Ltd FEASIBILITY REPORT, DPR PREPARATION, REPORT ON ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES AND OBTAINING MOEF CLEARANCE AND BID PROCESS MANAGMENT . FOR MUMBAI COASTAL ROAD PROJECT CHAPTER 11 11. Executive Summary: E.S 1. Introduction Mumbai reckoned as the financial capital of the country, houses a population of 12.4million besides a large floating population in a small area of 437sq.km. As surrounded by sea and has nowhere to expand. The constraints of the geography and the inability of the city to expand have already made it the densest metropolis of the world. High growth in the number of vehicles in the last 20 years has resulted in extreme traffic congestion. This has lead to long commute times and a serious impact on the productivity in the city as well as defining quality of life of its citizens. The extreme traffic congestion has also resulted in Mumbai witnessing the worst kind of transport related pollution. Comprehensive Traffic Studies (CTS) were carried out for the island city along with its suburbs to identify transportation requirements to eliminate existing problems and plan for future growth. -

103 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

103 bus time schedule & line map 103 Kamla Nehru Park (Malabar Hill) View In Website Mode The 103 bus line (Kamla Nehru Park (Malabar Hill)) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Kamla Nehru Park (Malabar Hill): 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM (2) R.C.Church: 6:10 AM - 11:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 103 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 103 bus arriving. Direction: Kamla Nehru Park (Malabar Hill) 103 bus Time Schedule 49 stops Kamla Nehru Park (Malabar Hill) Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM Monday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM R.C.Church Tuesday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM Ins Ashwini Hospital Wednesday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM Pilot Bunder Thursday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM Afghan Church Friday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM Colaba Post O∆ce Saturday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM Wodehouse Rd, Mumbai Colaba Bus Station Wood House 103 bus Info Direction: Kamla Nehru Park (Malabar Hill) Sasoon Dock / Fire Brigade Center Stops: 49 Trip Duration: 42 min Nanabhai Moos Marg (Upper Colaba Road), Mumbai Line Summary: R.C.Church, Ins Ashwini Hospital, Sasoon Dock / Colaba Fire Brigade Station Pilot Bunder, Afghan Church, Colaba Post O∆ce, Colaba Bus Station, Wood House, Sasoon Dock / Fire Brigade Center, Sasoon Dock / Colaba Fire Brigade Strand Cinema Station, Strand Cinema, Regal Cinema, Colaba Depot Shroff Lane, Mumbai (Electric House), Holy Name School (Colaba), Dr.Shamaprasad Mukherji Chowk, Hutatma Chowk Regal Cinema /Mumbai University, Hutatma Chowk (Mumbai University) / ( ), Khadi Bhandar, Colaba Depot (Electric House) -

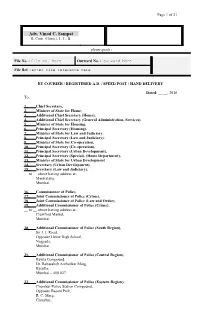

Adv. Vinod C. Sampat B

Page 1 of 31 Adv. Vinod C. Sampat B. Com. (Hons.), L. L. B. please quote : File No. : file no. here Outward No. : outward here File Ref. : enter file reference here BY COURIER / REGISTERED A.D. / SPEED POST / HAND DELIVERY Dated: __ __, 2016 To, 1. Chief Secretary, 2. Minister of State for Home, 3. Additional Chief Secretary (Home), 4. Additional Chief Secretary (General Administration, Services), 5. Minister of State for Housing, 6. Principal Secretary (Housing), 7. Minister of State for Law and Judiciary, 8. Principal Secretary (Law and Judiciary), 9. Minister of State for Co-operation, 10. Principal Secretary (Co-operation), 11. Principal Secretary (Urban Development), 12. Principal Secretary (Special), (Home Department), 13. Minister of State for Urban Development 14. Secretary (Urban Development), 15. Secretary (Law and Judiciary), __ to __ above having address at: Mantralaya, Mumbai. 16. Commissioner of Police, 17. Joint Commissioner of Police (Crime), 18. Joint Commissioner of Police (Law and Order), 19. Additional Commissioner of Police (Crime), __ to __ above having address at: Crawford Market, Mumbai. 20. Additional Commissioner of Police (South Region), Sir J. J. Road, Opposite Hume High School, Nagpada, Mumbai. 21. Additional Commissioner of Police (Central Region), Bawla Compound, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marg, Byculla, Mumbai – 400 027. 22. Additional Commissioner of Police (Eastern Region), Chembur Police Station Compound, Opposite Basant Park, R. C. Marg, Chembur, Page 2 of 31 Mumbai. 23. Additional Commissioner of Police (Western Region), Carter Road, Near Ashirwad Bungalow, Bandra (West), Mumbai. 24. Additional Commissioner of Police (North Region), Near Thakur College, Samta Nagar, Kandivali (East), Mumbai – 400 101. -

Mumbai & Goa Tour

MUMBAI & GOA TOUR 10 days / 9 nights Day 1 Arrival Meeting and assistance upon arrival at the airport and transfer to the hotel for check-in. Overnight stay at the Taj Mahal Palace & Tower hotel. Day 02 Mumbai After breakfast, cruise across the harbour (9 kms) to see Elephanta Caves noted for huge rock cuts. (Elephanta Caves remains closed on all Mondays). Later sightseeing tour of Mumbai, the commercial capital of India, includes Kamla Nehru Park, Hanging Gardens situated on the slopes of Malabar Hill offering a panoramic view of Marine drive, Chowpatty Beach, Prince of Wales Museum (closed on all Mondays), Mani Bhawan, Dhobi Ghat, Gateway of India & drive through the Crawford Market, Marine Drive & Flora Fountain. Overnight stay at the Taj Mahal Palace & Tower hotel. Day 03 Mumbai – Aurangabad Breakfast at hotel. Morning at leisure. Later on transfer to the airport to board flight for Aurangabad (flight AI-442, 03:00/03:50 pm). Meeting & assistance upon arrival at Aurangabad airport and transfer to hotel for check-in. Rest of the day at leisure. Overnight stay at the hotel Vivanta by Taj. Day 04 Aurangabad Breakfast at hotel. Later excursion to Ajanta Caves (approx. 100 km / 3h, closed on all Mondays), which date back to the 2nd century B.C. The 30 rock hewn caves are adorned with Buddhist sculptures and the frescoes portray the religious and secular life through eight centuries. Ajanta is famous for its paintings and sculptures, considered as master pieces of Buddhist religious art. Overnight stay at the hotel Vivanta by Taj. Day 05 Aurangabad After breakfast full day tour of Ellora Caves (29 km, closed on Tuesdays) encompassing 34 rock cut shrines representing Buddhist, Hindu & Jain art dating from the 4th to 9th century A.D. -

Electricity Bill Collection Centres

Customer Care (South) - Electricity Bill Collection Centres Timings Centre Name Address Tel. No. Mon. to Fri. 8.00 AM TO 6.00 PM Sat. New Administrative Bldg., BEST Head Office 9.15 AM TO 4.00 PM 22873154 Marg, Mumbai - 400 001. Sun. 9.15 AM TO 3.00 PM Hutatma Chowk, BEST Chowkey, Flora Fountain 8.00 AM TO 6.00 PM 22693282 Mumbai - 400 001. Backbay Depot, Captain Prakash 8.00 AM TO 12.30 Backbay 22152359 Pethe Marg, Mumbai - 400 005. PM 9.00 AM TO 1.30 PM Mint Road, Near G.P.O., Mumbai - Fort Market Sat. 22632482 400 001. 9.15 AM TO 1.30 PM Colaba Bus Station, Mumbai - 400 Colaba Bus Station 9.00 AM TO 1.30 PM 22164337 005. MCGM Head Office, Nagar Chowk, Boribunder 9.00 AM TO 2.00 PM 22060760 Mumbai - 400 001. Nr. Police Commissioner's Office, L. Crawford Market 8.00 AM TO 6.00 PM 22632483 Tilak Marg, Mumbai - 400 002. 8.00 AM TO 6.00 PM Vijay Vallabh Chowk, Bapu Khote Sat. Pydhonie 23434263 Marg, Mumbai - 400 003. 8.00 AM TO 12.30 PM Mahapalika Market Complex, Mumbai 8.00 AM TO 12.30 Dongri Market 23750365 - 400 009. PM 8.00 AM TO 6.00 PM Nr. Alankar Cinema, S.V.P. Road, Sat. Khetwadi 23825159 Mumbai - 400 004. 8.00 AM TO 12.30 PM 8.00 AM TO 12.30 Opp. Panchsheel Bldg., Manaji Raju PM Sat. Kamathipura 23054247 Marg, Mumbai - 400 008. 8.00 AM TO 12.30 PM Tardeo Marg, Tardeo Bus Stand Tardeo 8.00 AM TO 6.00 PM 23534631 (Pandey Compd.) Mumbai - 400 034. -

Aakash Tower

https://www.propertywala.com/aakash-tower-mumbai Aakash Tower - Bhuleshwar, Mumbai A perfect getaway after a tiring day at work, Aakash Tower by Aakash Associates at Bhuleshwar in Mumbai offers residential project that host 1 bhk apartments in various sizes available. Project ID: J396817118 Builder: Aakash Associates Location: Aakash Tower, Bhuleshwar, Mumbai (Maharashtra) Completion Date: May, 2021 Status: Started Description Aakash Tower is a residential project developed by Aakash Associates Infrastructure at Bhuleshwar in Mumbai offers spacious 1 bhk apartments in the size of 307 sqft. ut of the many world class facilities, the major amenities includes 24Hrs Water Supply, 24Hrs Backup Electricity, Covered Car Parking etc. The project is strategically located and provides direct connectivity to nearly all other major points in and around Mumbai. It is one of the most reputable address of the city with easy access to many famed schools, shopping areas etc. RERA ID : P51900012769 Amenities : 24 Hrs Backup Electricity Fire Safety Security Personnel Lift Covered Car Parking 24 Hrs Water Supply Aakash Associates Infrastructure is a well-known player in real estate industry, and their focus from day one has been to provide the best quality real estate products. Apart from that, they provide the best customer service and the uncompromising values. The company's main goal is to provide the best real estate services and earn the customer confidence. Features Luxury Features Security Features Power Back-up Lifts High Speed Internet Security Guards Intercom Facility Lot Features Exterior Features Balcony Reserved Parking Maintenance Maintenance Staff Rain Water Harvesting Gallery Pictures Elevation Location https://www.propertywala.com/aakash-tower-mumbai Landmarks Hotel West End Hotel (<2km), Ripon Palace Hotel (<2km), Hotel New Bengal (<2km), Taj Mahal Tower Mumbai (<5km), Residency Hotel (<3km), ITC Grand Central Hotel Mumbai (<7…Four Seasons Hotel Mumbai (<6km), The Ambassador Marine Drive (<4km…Bentley, Hotel Windsor Mumbai (<3km), Abode Bombay (<5km), The St.