Bangalore Based Ngos, Bangalore Invisible City Makers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alumni Association of MS Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences

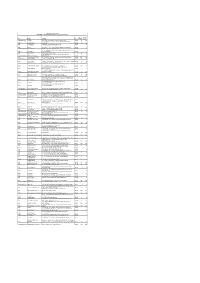

Alumni Association of M.S. Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences (SAMPARK), Bangalore M.S. Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences Department of Automotive & Aeronautical Engineering Program Year of Name Contact Address Photograph E-mail & Mobile Sl NO Completed Admiss ion # 25 Biligiri, 13th cross, 10th A Main, 2nd M T Layout, [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive 574 2013 Pramod M Malleshwaram, Bangalore- 9916040325 Engineering) 560003 S/o L. Srinivas Rao, Sai [email protected] Dham, D-No -B-43, Near M. Sc. (Automotive m 573 2013 Lanka Vinay Rao Torwapool, Bilaspur (C.G)- Engineering) 9424148279 495001 9406114609 3-17-16, Ravikunj, Parwana Nagar, [email protected] Upendra M. Sc. (Automotive Khandeshwari road, Bank m 572 2013 Padmakar Engineering) colony, 7411330707 Kulkarni Dist - BEED, State – 8149705281 Maharastra No.33, 9th Cross street, Dr. Radha Krishna Nagar, [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Venkata Krishna Teachers colony, 571 2013 0413-2292660 Engineering) S Moolakulam, Puducherry-605010 # 134, 1st Main, Ist A cross central Excise Layout [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Bhoopasandra RMV Iind 570 2013 Anudeep K N om Engineering) stage, 9686183918 Bengaluru-560094 58/F, 60/2,Municipal BLDG, G. D> Ambekar RD. Parel [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Tekavde Nitin 569 2013 Bhoiwada Mumbai, om Engineering) Shivaji Maharashtra-400012 9821184489 Thiyyakkandiyil (H), [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Nanminda (P.O), Kozhikode / 568 2013 Sreedeep T K m Engineering) Kerala – 673613 4952855366 #108/1, 9th Cross, themightyone.lohith@ M. Sc. (Automotive Lakshmipuram, Halasuru, 567 2013 Lohith N gmail.com Engineering) Bangalore-560008 9008022712 / 23712 5-8-128, K P Reddy Estates,Flat No.A4, indu.vanamala@gmail. -

Yellappa S/O Late Sri Nallappa Aged About 59 Years R/A No

1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA, BENGALURU DATED THIS THE 10 th DAY OF AUGUST, 2015 BEFORE THE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE RAM MOHAN REDDY REVIEW PETITION NOs. 367 OF 2015 AND 514-517 OF 2015 IN WRIT PETITION NOs.48498-502 of *2013 BETWEEN: YELLAPPA S/O LATE SRI NALLAPPA AGED ABOUT 59 YEARS R/A NO. 92, CHIKKALAKSHMAIAH LAYOUT, HOSUR ROAD, BANGALORE – 560 029. .. PETITIONER (BY SRI.M.R.RAJAGOPAL, ADV.) AND: 1. P. VENKATESHAN S/O SRI POUN RAJULU AGED ABOUT 57 YEARS R/AT NO.7, KAVERI LAYOUT, SUDDAGUNTEPALYA, DARMARAM COLLEGE POST, BANGALORE – 560 029. *Corrected vide chamber order dated 19.08.2015 2 2. SMT. H SHIVANI SHETTY AGED ABOUT 48 YEARS W/O SHRI H .VEERARAJ SHETTY R/AT NO.7, KAVERI LAYOUT, SUDDAGUNTEPALYA DARMARAM COLLEGE POST, BANGALORE – 560 029. 3. SHRI. H .VEERARAJ SHETTY AGED ABOUT 51 YEARS S/O SHRI H.CHANDRASEKARA SHETTY R/AT NO.7, KAVERI LAYOUT SUDDAGUNTEPALYA DARMARAM COLLEGE POST, BANGALORE – 560 029. 4. SMT. T.A. AMALORPAVI AGED ABOUT 57 YEARS W/O SHRI P VENKATESHAN R/AT NO.7, KAVERI LAYOUT SUDDAGUNTEPALYA DARMARAM COLLEGE POST, BANGALORE – 560 029. 5. THE DISTRICT REGISTRAR OF STAMPS NO.2722, 2 ND FLOOR 12 TH MAIN ROAD, 4 TH BLOCK JAYANAGAR, BANGALORE – 560 011. ... RESPONDENTS THESE REVIEW PETITIONS ARE FILED UNDER ORDER 47 RULE 1 OF CPC PRAYING TO REVIEW THE ORDER DATED 6.4.2015 PASSED BY THIS HON’BLE COURT IN W.P.Nos.48498-502/2013 AND DISMISS THE WRIT PETITIONS WITH COSTS. 3 THESE REVIEW PETITIONS COMING ON FOR ORDERS THIS DAY, THE COURT MADE THE FOLLOWING: O R D E R These petitions are filed by the 1 st respondent in W.P.Nos.48498-502/2013 to review the order dated 6.4.2015 allowing the writ petitions. -

FOLIO NAME 1 ADDRESS PIN NO. of SHARES DIV AMT (In Rs.) IN30113526141278 a a SINDHU NO 5 PRABHATH,3RD MAIN VYALIKAVAL,BANGAL

KENNAMETAL INDIA LIMITED UNCLAIMED / UNPAID DIVIDEND DATA 2014-15 (I) AS ON 30-04-2018 NO. OF DIV AMT FOLIO NAME_1 ADDRESS PIN SHARES (in Rs.) IN30113526141278 A A SINDHU NO 5 PRABHATH,3RD MAIN VYALIKAVAL,BANGALORE 560003 100 200 97 3RD MAIN 2ND CROSS,MICO LAYOUT, MAHALAKSHMIPURAM, A0675 A B MENDONCE BANGALORE 560086 80 160 A0663 A C POOVANNA F-301 PURVA PAVILION,HEBBAL,BANGALORE 560024 5 10 A0666 A C POOVANNA F 301 PURVA PAVILION,HEBBAL,BANGALORE 560024 1 2 A0662 A GOPAL KENNAMETAL INDIA LTD,8/9TH MILE,TUMKUR ROAD,BANGALORE 560073 1 2 IN30192630446648 A S ASHOK KUMAR NO H-93,TANK ROAD,,DODDABALLAPUR 561203 5 10 200269 KENNAMETAL INDIA LTD,8/9TH MILE TUMKUR ROAD,(R & D EPG A0673 A S NAGARAJ DEPT),BANGALORE 560073 1 2 CK237 ABHAI KUMAR 3/17 JAWAHAR NAGAR,JAIPUR 0 200 400 WARD NO 4,ADINATH AGENCIES,SHIVAJI NAGAR, KHAMGAON 1302310000042420 ABHAY VIJAY ZAMBAD ROAD,NANDURA 443404 3 6 CA007 AHMED MOHAMED AFINIA JANTA COLONY B 3/41,SINGH NIWAS,JOGESHWARI EAST,MUMBAI 400060 2880 5760 1203470000002215 AMEET GANGULY I - 1647,C. R. PARK,NEW DELHI 110019 100 200 A0413 AMITA JINDAL C/O DR. PAWAN JINDAL,137, URBAN ESTATE,SECTOR 7,AMBALA CITY (HR) 134002 20 40 A0653 ANAHITA A KOHLI 1/20 KUMAR CITY,KALYANI NAGAR,,PUNE 411006 1000 2000 A0360 ANAND NARAYAN TANDON 41A, GREENVIEW APARTMENT,SECTOR 15A, NOIDA 201301 200 400 NO 97 6TH CROSS,32ND MAIN ITI LAYOUT,J P NAGAR IST A0672 ANAND SINGH C J PHASE,BANGALORE 560078 1 2 9/17, CHANDRANAGAR HOUSING,SOCIETY, POONA-SATARA ROAD,,OPP. -

Unpaid Dividend-17-18-I3 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 696104.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 54.00 23-May-2025 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 23-May-2025 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE ROOM NO 6 G 15 M L CAMP 12044700-01567454- Amount for unclaimed and A ARUNCHETTIYAR AKCHETTIYAR INDIA Maharashtra 400019 10.00 23-May-2025 MATUNGA MUMBAI MI00 unpaid -

Licence Issued 2010

1 LICENCE ISSUED 2010 Sl. No Licence Name of the Name & Address of Area of Period of Phone Number/ E-mail adress . No. Agency / the Security Operation License Mobile Number Applicant Services From To Issued on 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1. 1. H.Prabhakar Tiger Security Bangalore (U) 02.01.2010 to 080- 2204724/ Tiger.securityserv (EX. BSF) Services. District only. 01.01.2015 9448553280 [email protected] Tiger Security Sri Sanjaya Tower, Issued on: Fax: 26604724 m Service Shop no. G-5 & G-6, 02.01.2010. Subbaram Chetty road, Basavanagudi, Bangalore-4. 2. 2. D.S. M/S Novel Security All over 02.01.2010 to 080- 23326622/ [email protected] Raghavendra Services. Karnataka 01.01.2015 9448496650 m M/S Novel No.12, 1 ST Floor, Dr. State Issued on: Fax: 23326655 Security Services. Raj Kumar road, 1 st 02.01.2010. block, Rajajinagar, Bangalore-10. 3. 3. Ashith Mohan G-I Security of India All over 03.02.2010 to 080 -41127005/ Bangalore@gisecu Luthra pvt, Ltd. Karnataka 02.02.2015 9342467370 rity.com G-I Security of #38/05, Berlie street, State Issued on: India pvt, Ltd. Hosur road, 03.02.2010. LangFord town, Bangalore-25 4. 4. C V Rao RAXA Security Bangalore (U), 04.02.2010 to 080-40534335/ Pandith_nrs@yah I.P.S-(Retd.) Services Ltd. Uttar 03.02.2015 9980137378 oo.co.in RAXA Security #08/01, Kings street Kannada & Issued on: Fax: 22122625 Services Ltd. of Richmond road, Dakshina 04.02.2010 Bangalore-25 Kannada. 5. -

2017-18 Guidance Value for the Immovable Properties Coming Under the Jurisdiction of Shanti Nagar Sub-Register Office

2017-18 Guidance value for the Immovable Properties coming under the jurisdiction of Shanti Nagar Sub-Register Office. Residential Sites Apporoved Apartments/Flats/Villament By Local Constructed on Residential Sites Organization/Competent approved by competent Authority/Local SI NO Hobli/Village/Ward/Road/Area Name Athourity Organization (Rupees per Square Meter For Super (Rupees in per Squre Meter) Built up Area) 1 2 3 4 Shanthinagar 1 Shanthinagar Main Road 85500 Shanthinagar Main Road 1,2,3 and 4th 2 58000 Cross Roads 3 Shanthinagar 1st Street 58000 Shanthinagar A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, J, N, 4 39100 O, P, Q, R & S 5 Double Road, K H Road 118400 Ramarao Maane layout, 6 45600 Akkithimmanahalli 7 Aga Garden Slum 24900 8 Kolkar Lakshmaiah Garden 39100 9 Kolandappa Garden 39100 10 Muthanna Garden 39100 11 Lakshmi Road 85300 12 Lakshmi Main Road, Swathi Main Road 85300 13 Swathi Road 88800 Swathi Main Road 1,2,3,4,5 Cross Roads 14 74100 15 Jalakanteshwara Road 54500 16 Jalakanteshwara Main Road 54500 17 Nanjappa Road 85500 18 Nanjappa Main Road 85500 19 Nanjundappa Street 85500 20 Basappa Road 85500 21 Shanthi Main Road 85500 22 E to F Slum, A to F and P to U Roads 24900 23 Andree Road 85500 24 V to Z Slum 19000 25 Hosur Road 127900 26 Long Ford Road 113700 27 Long Ford Road Adjacent Cross Roads 94800 28 Berlie Street 94800 29 Berlie Street Cross 81700 30 Abbaiah Garden 58700 31 1 to 5th Cross Roads Abbaiah Layout 52100 32 1st Main Road Abbaiah Layout 58700 33 Church Road 81700 34 Eagle Road 94800 35 Long Ford Town 113700 36 Lakshmi Road 5th Cross Road 81700 37 Church Road K.M.Shetty Layout 74600 38 Berlie Street Bethmal Layout 60400 39 Munimarappa Street 58700 40 Murugesh Modaliyar Road 58700 41 Papegowda Street 58700 42 Uttaregowda Street 58700 43 Sercular Street 58700 44 Gosaiah Street 58700 45 Lakshmipathi Street 58700 46 Bangiyappa Garden 58700 47 Muniswamy Garden 58700 48 Yellamma Garden 58700 49 Bheemanna Garden 58700 50 East End Bheemanna Garden 64000 51 East Road 1,2,3rd Cross Roads 48000 52 Subbanna Layout 48000 53 Central Street A.T.Halli 48000 54 P.K. -

Sl.No. Customer Name Address 1 a N SRINIVASA a M NARAYANAPPA ANDKEMPAMMA , SB-1291

Sl.No. Customer Name Address 1 A N SRINIVASA A M NARAYANAPPA ANDKEMPAMMA , SB-1291 , . BANGALORE 2 ABDUL KHUDDUS JABARTRAVELS , 19/3 A.V.ROAD KALASIPALYAM , . BANGALORE 3 ABDUL LATHIF K SB-1370 , . , . BANGALORE 4 ABDUL RAHAMAN T HAJIRA SULTA 17 1STFLOOR 3RDCROSS , T.C.MROYANROAD , . BANGALORE 5 ABDUL RAHSEED TN.109 BATTERYDEPT. , 1/1 VITTALMALLYAROAD UBLTD , . BANGALORE 6 ABDUL RAWOOF SB-1331 , . , . BANGALORE 7 ABDUL SALAM SARI SONS RICEBRAN CATTLEFEED&GENERALMERCHANTS , NO16 TCMROYANROAD , . BANGALORE 8 ABDUL SHUKOOR SENIORINSPECTOROFCO-OPSOCIETIES , O/OJRCS BANGALOREDIVISION , . BANGALORE 9 ABDUL WAJID SB-2797 , . , . BANGALORE 10 ADARSH ROAD CARRIERS BANGALORE , . , . BANGALORE 11 ADIKESHAVAN A.167 BINNYPET , . , . BANGALORE 12 ADINARAYANA B N 3/2 ROOMNO.1 ISTMNRD ICROSS , CHAMARAJPET , . BANGALORE 13 ADINARAYANAIAH C 560/11 AVENUEROAD , . , . BANGALORE 14 ADISESHA MURTHY M R 33/3 4THMAINROAD , CHAMARAJPET , . BANGALORE 15 AGARA CO OP SOCIETY LIMITED AGARA , BANGALORESOUTHTALUK , . BANGALORE 16 AGNES NAZAREETH NO.15 4THMAIN GAYATHRINAGAR , 7THCROSS , . BANGALORE 17 AKHILAKHATOON FEMALEHEALTHASSISTANT BELEDEVALAYA , SUB-CENTRE KUNIGAL(4367) , . BANGALORE 18 AKILA BHARTHKURAHINA SHETTY YU 19 NEWHIGHSCHOOLROAD , V.V.PURAM , . BANGALORE 19 AKKAYAMMA SB-992 , . , . BANGALORE 20 ALL INDIA SHEDULED CASTE DEVEL SOCIETY , . , . BANGALORE 21 ALL INDIA VEERASAIVA MAHASABHA KARNATAKASTATEUNIT , . , . BANGALORE 22 ALLAH BAKASH S PSI CENTRALPOLICESTATION , CHAMARAJPET , . BANGALORE 23 AMAREGOWDA BYYAPURAKALAGOWDAJIPOST , LINGASUGURTQ. , . BANGALORE 24 AMARNATH A JIGANI ANEKALTQ. , . , . BANGALORE 25 AMARNATH L 7 12MAINROAD , RAGHAVENDRABLOCK SRINAGAR , . BANGALORE 26 ANAND B M JAYANAGAR , BANGALORE , . BANGALORE 27 ANAND B S STAFF NO119/5MPVHOUSE16THMAIN , 16MAINROADVIJAYANAGARBLORE , . BANGALORE 28 ANAND ENTERPRISES 639 22MAINROAD , 4THBLOCKJAYANAGAR , . BANGALORE 29 ANANDA H K 42/6 ICROSS VITTALNAGAR , CHAMRAJPET , . BANGALORE 30 ANANDA KUMAR M 3/1A , 3RDCROSS 6THMAIN NR.COLONY , . BANGALORE 31 ANANDA RAO K 309/5 IFLOOR , 40THCROSS JAYANAGAR 8THBLOCK , . -

IEPF 2 Data for Web Upload.Xlsx

Sasken Technologies Limited - Unclaimed dividend as on 18th July, 2018 - FINAL DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2016-17 Holder 1st Name Holder 2nd Name Holder 3rd Name Father / Husband 1st Father / Husband 2nd Father / Husband 3rd Address Pin Folio No. DP ID - LIENT ID Amount Proposed Name Name Name Code Transferred date of (Rs.) transfer to IEPF A SRINATH ANANTHASWAMY SUBHODAYA,KESTON ROAD, VELLAYAMBALAM, TRIVENDRUM KERALA 695003 SCT0000947 - 45.00 24-AUG-2024 A SOMASEKHAR NA C/O G PITCHAIAH D NO 40-6-27 LABBIPET VIJAYAWADA, ANDHRA PRADESH 520010 IN301895-10759413 225.00 24-AUG-2024 A C ARAVIND NA # 77/C, I FLOOR, 18TH CROSS, 6TH MAIN, MALLESWARAM BANGALORE 560055 SCT0000180 - 450.00 24-AUG-2024 A V HARIPRASADREDDY A V CHALAMAREDDY 231/B SRI KALA NILAYAM, S G PALYA C V RAMANNAGAR BANGALORE 560093 SCT0001311 - 135.00 24-AUG-2024 A SRINIVASAN AYYAPPA NAICKER K 381/5, NETHAJI STREET LAKSHMIPURAM P O PERIYAKULAM TALUK THENI, TAMILNADU 625523 IN301895-10217670 225.00 24-AUG-2024 A K SUNDARAGIRI A KRISHNASAMY 5 ANUMANDHARAYAN KOYIL STREET TRIPLICANE, TIRUVALIKKENI CHENNAI TAMILNADU 600005 12038400-00134661 112.50 24-AUG-2024 A MANJULA NA 5-5-859, GOSHAMAHAL, HINDI NAGAR, HYDERABAD ANDHRA PRADESH 500012 12040000-00070444 900.00 24-AUG-2024 A ANITHA A SRINIVAS VILLA NO 37 SHANTHI NIKETHAN BESIDE GODREJ GOWDON QUTHUBULLAPUR MANDAL KOMPALLE KV RANGAREDDY 500014 IN300394-12985929 67.50 24-AUG-2024 HYDERABAD AAKELABANOO MOHMEDSAID KAPADIAKAPADIA MOHMEDSAID 2/3152, PAHADKHAN STREET, SAGRAMPURA SURAT GUJARAT 395002 12041500-00003311 45.00 24-AUG-2024 ABDUL SAMAD -

BRUHAT BANGALORE MAHANAGARA PALIKE No.E.E

BRUHAT BANGALORE MAHANAGARA PALIKE No.E.E. (BTM) JE/e-proc/ 13 /2013-14 Office of the Executive Engineer BTM Layout Division Dispensary Building Adugodi Bangalore -30 Dated: 30-12-2013 SHORT TERM TENDER NOTIFICATION (Single Cover) (Through GOK e–Procurement Portal only) Tenders on item rate basis are invited by the undersigned for the work mentioned below from the registered contractors of Bruhat Bangalore Mahanagara Palike or equivalent registration with CPWD / KPWD / Railways / MES or any State Government Organisations Dated:- 13-01-2014 up to 4:00 P.M. The opening of the BID will be on 15-01-2014 at 4.05 P.M. The Tender Document can be downloaded from the GOK e-Procurement (https://eproc.karnataka.gov.in) Website on payment of prescribed fee noted against each item of work (non refundable) in the form of e-Payment through e-Procurement Platform. The Tenderer should accompany a copy of the Registration Certificate valid upto the year of 2013-2014 and shall be submitted through e-Procurement Portal. Approxim Cost of ate Period EMD Eligibility Tender Sl Ward value of of Name of the work (in of form in No No work Compl Rupees) Contractors Rs (Non- (Rs in etion document (Rs) Lakhs) 3rd Call Pot Holes filling to the Roads As per E- Class lll 365 1 146 for the year 2013-14 in Ward 10.00 25000/- procurement Above Days No. 146 (Lakkasandra). portal Repairs and Improvements to As per E- Governament School Buildings Class ll 90 2 146 20.00 50000/- procurement in Ward No. -

Sl No Branch Name Address 1 0251 NAGAMMA NO.167, R.V.ROAD V.V.PURAM .,,,BANGALORE-560004 2 0251 VINITHA MOREY No.25 KMH Road 6Th Main 6Th BLOCK,R.T

List of main Branch Inoperative Saving bank Accounts As On 31-Jan-2021 Sl No Branch Name Address 1 0251 NAGAMMA NO.167, R.V.ROAD V.V.PURAM .,,,BANGALORE-560004 2 0251 VINITHA MOREY No.25 KMH Road 6th Main 6th BLOCK,R.T. N,AGAR, GANGANAGAR,,BANGALORE-560032 3 0251 LINGAPPA Y NO 126 V S GARDEN,,,BANGALORE-560023 4 0251 HARISH BABU H # 1-178/4-4, 5TH CROSS,, I FLOOR, I BLOC,K, KORAMANGALA,,,BANGALORE- 560001 5 0251 RAJESH M H 967, 3RD CROSS, I MAIN,I BLOCK HAL III S,TAGE, INDIRANAGAR .,,BANGALORE- 560075 6 0251 VENKATESHA S V C/O S.V.PARAMESHA 132, R.V.ROAD,,,BANGALORE-560004 7 0251 BHARADUAJ T K #3, SUBBARAJU LAYOUT 15TH CROSS, 6TH MAI,N,,,BANGALORE-560030 8 0251 SUBBARAMAIH M S #105, OUTHOUSE DR.A N KRISHNA RAO ROAD V, V PURAM,,BANGALORE- 560004 9 0251 SUBBARAYA R N #14/2, RANGAPPA STREET CHIKAMAVALLI .,,,BANGALORE-560004 10 0251 KESAVAN G #HOTEL MAYURI SPICE CORRIDER MADIWALA PO,LICE STATION HOSUR MAIN ROAD,,BANGALORE-560068 11 0251 MOHAN B 3/1,1ST CROSS ANNIPURA SUDHAMANAGARA,,,BANGALORE-560027 12 0251 NAGESHA K.S CAP SECTION, II FLR, MAIN BUILDING,O/O T,HE ACCOUNTANT GENERAL AUDIT -I MAIN BUIL,DING,O/O THE ACCOUNT,BANGALORE-560018 13 0251 POOJA J # 267/2, II MN, II BLOCK, CHENGAIAH LAYO,UT,,,BANGALORE-560028 14 0251 REVATHI # 35,YELLAPPA STREET,,,BANGALORE-560004 15 0251 LALITHA.M # 32/35, NEW CROSS ROAD,,,,BANGALORE-560004 16 0251 NAGAMANI N W/O G NAGHABHUSHAN REDDY,NO 55/3 1 ST MAIN ROAD,TEACHERS COLONY,BANGALORE-560070 17 0251 SHAMITHA K M NO.8(7/3) II CROSS, BEHIND SHANIDEVARA T,EMPLE, R.M.V II STAGE, N.S. -

BANGALORE NORTH-3 29280600334 HS N3 Lingarajapurapvt

Page 1 SCHCAT_DES SCHCD SCHNAME BLK CLUNAME SCHMGT_DESC TCHNAME TCH PHONE1 MOBILE1 POSTALADDR NEW CAMBRIDGE GRUHALAKSHMI S R S EDUCATION TRUST , NEW CAMBRIDGE SCHOOL H 29280207603 SCHOOL N1 LAYOUT Pvt. Unaided Primary SAVITHA HM 9141737389 M T LAY OUT NAGASANDRA BANGALORE -73 ST JOSEPH GRUHALAKSHMI CHIDANANDA 29280209202 SCHOOL N1 LAYOUT Pvt. Unaided Primary PPA HM 9448880653 ST. JOSEPH SCHOOL . N.G HALLI--BANGALORE-73 NATIONAL PUBLIC SCHOOL GRUHALAKSHMI Primary with 29280209208 SHIVAPUR N1 LAYOUT Pvt. Unaided Upper Primary MURALI M HM 9886056172 NATIONAL PUBLIC SCHOOL, SHIVAPUR-BANGALORE-73 AKSHRA SRI VIDYA AKSHARA SRI VIDYA EDUCATION TIGALARAPALYA EDUCATIONA GRUHALAKSHMI Primary with KARIVOBANAHALLI 29280202003 L S N1 LAYOUT Pvt. Unaided Upper Primary SHANTHA HM 9742015587 BANGALORE -58 New Indian NEW INDIAN NATIONAL SCHOOL TIGALARAPALYA National school GRUHALAKSHMI Primary with VIJAYALAKSH PEENYA 2ND STAGE 29280202004 pilva N1 LAYOUT Pvt. Unaided Upper Primary MI C HM 28367155 9379439523 BANGALORE-91 ST.ANNS SCHOOL 11TH CROSS .BALAJINAGAR THIGALARAPALYA ST ANNS ENG GRUHALAKSHMI Primary with ANNAPURNA B PEENYA 2ND STAGE 29280202005 SCHOOL N1 LAYOUT Pvt. Unaided Upper Primary N HM 9900693456 BANGALORE SRI SRINIVASA HPS GRUHALAKSHMI Primary with 29280231602 SHIVAPURA N1 LAYOUT Pvt. Unaided Upper Primary JAYALAKSHMI HM SRI SRINIVASA SCHOOL SHIVAPUR BANGALORE - 73 BHAVASARA VIIDYASAMST GRUHALAKSHMI Pr. with Up.Pr. KALPHANA 29280209103 E N1 LAYOUT Pvt. Unaided sec. and H.Sec. KUSHAL J HM 69570242 9242370563 BHAVASARA VIDYA SAMSTE N. G HALLI--B-73 MANJULA PUBLIC GRUHALAKSHMI Pr. Up Pr. and ANNEGOWDA MANJULA PUBLIC SCHOOL NELAGADARANAHALLI 29280227243 SCHOOL N1 LAYOUT Pvt. Unaided Secondary Only L HM 22724903 9731477341 BANGALORE - 73 VISHWA BHARATHI VIDYA GRUHALAKSHMI Pr. -

Prosocial Behaviour of Citizens in Bangalore City, Karnataka State

SCHOLEDGE International Journal Of SCHOLEDGE Publishing Worldwide Multidisciplinary & Allied Studies www.theSCHOLEDGE.org ISSN 2394-336X, Vol.06, Issue 10 (2019) Email: [email protected] Pg 105-112. ©Publisher Paper URL: link.thescholedge.org/1090 Prosocial Behaviour of Citizens in Bangalore City, Karnataka State Rachita Rao, IV Sem MSW CCP student, Department of Sociology and Social Work, Christ (Deemed to be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. Dr. Sheeja Ramani B Karalam, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology and Social Work, Christ (Deemed to be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. Abstract Of late there is an increase in the number of harmful incidence in public spheres. Hence, the prosocial behaviour of bystanders is important to support persons in such incidents. This study aims at understanding the prosocial behaviours of bystanders of the metropolitan city in the southern part of India. A qualitative exploratory study was conducted with six respondents aged between 30-50 years. In-depth interviews were conducted, audio-recorded and transcribed later. The data were analyzed using thematic analysis. The qualitative analysis found two major themes such as factors that encourage citizen’s prosocial behaviour that includes sense of belongingness, empathy, positive experiences, convenience and factors that discourage citizen’s prosocial behaviour that include fear of being blamed, fear of being attacked, corruption and time-consuming procedures, barriers in understanding language, negative experiences. Keywords: prosocial behaviour, citizen, bystander Introduction Humans are social beings who depend on one another for everyday interactions. These interactions have a motive to either benefit themselves and others. Actions that aim to benefit others fall under acts of charity.