Jazz Improvisation Method Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

Short Takes Jazz News Festival Reviews Jazz Stories Interviews Columns

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC SHORT TAKES JAZZ NEWS FESTIVAL REVIEWS JAZZAMANCA 2020 JAZZ STORIES PATTY WATERS INTERVIEWS PETER BRÖTZMANN BILL CROW CHAD LEFOWITZ-BROWN COLUMNS NEW ISSUES - REISSUES PAPATAMUS - CD REVIEWS OBITURARIES Volume 46 Number 2 April May June Edition 2020 Ed Schuller (bassist, composer) on GM Recordings My name is Eddy I play the bass A kind of music For the human race And with beauty and grace Let's stay on the case As we look ahead To an uncertain space Peace, Music Love and Life" More info, please visit: www.gmrecordings.com Email: [email protected] GM Recordings, Inc. P.O. Box 894 Wingdale, NY 12594 3 | CADENCE MAGAZINE | APRIL MAY JUNE 2016 L with Wolfgang Köhler In the Land of Irene Kral & Alan Broadbent Live at A-Trane Berlin “The result is so close, so real, so beautiful – we are hooked!” (Barbara) “I came across this unique jazz singer in Berlin. His live record transforms the deeply moving old pieces into the present.” (Album tip in Guido) “As a custodian of tradition, Leuthäuser surprises above all with his flawless intonation – and that even in a live recording!” (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) “Leuthäuser captivates the audience with his adorable, youthful velvet voice.” (JazzThing) distributed by www.monsrecords.de presents Kądziela/Dąbrowski/Kasper Tom Release date: 20th March 2020 For more information please visit our shop: sklep.audiocave.pl or contact us at [email protected] The latest piano trio jazz from Quadrangle Music Jeff Fuller & Friends Round & Round Jeff Fuller, bass • Darren Litzie, piano • Ben Bilello, drums On their 4th CD since 2014, Jeff Fuller & Friends provide engaging original jazz compositions in an intimate trio setting. -

Clint Fisher and His Musical Buddies

EDITOR: Amelia Martin ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sarah Fitzjarrald CONSULTING EDITOR: CONTENTS Carolyn Pollan GUEST WRITER: VOL VIII, NO. 1 APRIL, 1984 Doc Miller PROOF READERS: Letter From Editors 2 Pam Pearce Alphonso Trent, One of the Best 3 Dr. Larry Pearce Mary Nell Euper Hammer's Bands 7 Rosalie Platt Amrita Grotto Band 9 Col. C.B. "Pat" Porter Jimmie Grace and His Ozarkians 10 PHOTOGRAPHIC STAFF David King The Southerners, Edgar A. Robinson, Director 12 INDEXING Doc Miller's Orchestras 14 Floy Looper Clint Fisher and His Musical Buddies 16 OFFICE STAFF Del Conger Fred Rose 18 Felix Thomson Wayne Redden and His Arkansas Valley Boys 19 Thelma Black Velma Barber Froebel E. Lee 19 Frank Jedlicka Heart Throbs 20 BOARD AND OFFICERS: Paul Lewis 20 Amelia Martin, Pres. Chris Allen, V.P. Calvin Carter and the Border City Ramblers, Mary Nell Euper, Sec. Rhonda "Kye'Tleming 21 Donald Peer, Treas. Floy Looper, Corres. Sec. News & Opportunities 22 Wayne Bledsoe Book Notes: Fort Smith, Siloam Shorts, Del Conger Fire In The Hole 25 Gilmer Dixon Sarah Fitzjarrald Marriage Book B, Fort Smith District, Mary Lou Jacobsen Sebastian County, Arkansas 26 Rosalie Platt Col. C.B. (Pat) Porter Corrections, Marriage Book A 32 Felix Thomson Contents, Past Issues 34 Thelma Wray 1884 Newspapers Excerpts 35 Membership in the Fort Smith Historical Index 49 Society includes subscription to The Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society, which is published semi-annually. Year begins Jan. 1 COVER: Some of Fort Smith's "Big Band Era" Bands and Orchestras and ends Dec. 31. «Copyright 1984 ISSN 0736 4261 For membership, send dues with your name By the Fort Smith Historical Society, Inc. -

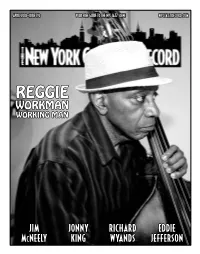

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

Full Biography

FULL BIO For forty years, pianist/composer and Fulbright Scholar ARMEN DONELIAN has distinguished himself in 25 countries as a performer, recording artist, master class leader and with his published writings. Donelian’s music is a distinctive blend of 20 influences including his Armenian origin, his Classical technique, and his association with some of the biggest names in Jazz. And, according to Metronom Magazine (1986), he achieves this fusion In such a natural way that one can tell it’s a master’s work. “The best time to learn music,” says Davis and John Coltrane. “Folk, Rock, Dixieland, Jazz, Church, Show and Society music – I played pianist Armen Donelian, “is when you’re them all while growing up,” says Donelian. young, while the brain synapses are still open and fresh. I started playing by ear “In college, I made money by accompanying when I was 5 or 6, and started classical theater and dance classes, providing cocktail music piano lessons when I was about 7 at the at a restaurant on campus and playing and Westchester Conservatory of Music. I arranging for an 8-piece Jazz/Rock band. After was lucky to have parents who supported graduation, I had no gigs, no direction, and lived at my musical aspiration.” home for a few months. My ex-girlfriend’s mother told me, ‘Armen, nothing is going to happen unless As a child, Armen absorbed the sound of you make it happen.’ Armenian, Turkish, Greek and Middle Eastern music at social gatherings and “So, after graduating from Columbia University in from records his father played at home. -

Discografía De BLUE NOTE Records Colección Particular De Juan Claudio Cifuentes

CifuJazz Discografía de BLUE NOTE Records Colección particular de Juan Claudio Cifuentes Introducción Sin duda uno de los sellos verdaderamente históricos del jazz, Blue Note nació en 1939 de la mano de Alfred Lion y Max Margulis. El primero era un alemán que se había aficionado al jazz en su país y que, una vez establecido en Nueva York en el 37, no tardaría mucho en empezar a grabar a músicos de boogie woogie como Meade Lux Lewis y Albert Ammons. Su socio, Margulis, era un escritor de ideología comunista. Los primeros testimonios del sello van en la dirección del jazz tradicional, por entonces a las puertas de un inesperado revival en plena era del swing. Una sentida versión de Sidney Bechet del clásico Summertime fue el primer gran éxito de la nueva compañía. Blue Note solía organizar sus sesiones de grabación de madrugada, una vez terminados los bolos nocturnos de los músicos, y pronto se hizo popular por su respeto y buen trato a los artistas, que a menudo podían involucrarse en tareas de producción. Otro emigrante aleman, el fotógrafo Francis Wolff, llegaría para unirse al proyecto de su amigo Lion, creando un tandem particulamente memorable. Sus imágenes, unidas al personal diseño del artista gráfico Reid Miles, constituyeron la base de las extraordinarias portadas de Blue Note, verdadera seña de identidad estética de la compañía en las décadas siguientes mil veces imitada. Después de la Guerra, Blue Note iniciaría un giro en su producción musical hacia los nuevos sonidos del bebop. En el 47 uno de los jóvenes representantes del nuevo estilo, el pianista Thelonious Monk, grabó sus primeras sesiones Blue Note, que fue también la primera compañía del batería Art Blakey. -

The Black Power Movement

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 1: Amiri Baraka from Black Arts to Black Radicalism Editorial Adviser Komozi Woodard Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 1, Amiri Baraka from Black arts to Black radicalism [microform] / editorial adviser, Komozi Woodard; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. p. cm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide, compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. ISBN 1-55655-834-1 1. Afro-Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—Sources. 3. Black nationalism—United States— History—20th century—Sources. 4. Baraka, Imamu Amiri, 1934– —Archives. I. Woodard, Komozi. II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Lewis, Daniel, 1972– . Guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. IV. Title: Amiri Baraka from black arts to Black radicalism. V. Series. E185.615 323.1'196073'09045—dc21 00-068556 CIP Copyright © 2001 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-834-1. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................ -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Jeff Rupert Saxophone Master Class

Jeff Rupert Saxophone Master Class I Saxophone Assembly and maintenance Holding the instrument. The neck and mouthpiece assembly. Checking key mechanisms. Checking for leaks, and clogged vents. Maintaining the lacquer. Setting the instrument down. II Posture The Back and neck. Legs and knees. III Breathing and Breath flow Inhaling. Exhaling. Breath solfège IV The Oral Cavity and the Larynx. V Embouchures for playing the saxophone. Variance in embouchure technique. The embouchure and breathing. VI Daily Routines for practicing the saxophone. Daily routines and rituals. Playing the mouthpiece. Playing the mouthpiece with the neck. Overtone exercises. VII Articulation Single tonguing. Doodle tonguing. Alternate articulations specific to jazz. Double tonguing. VIII Practice patterns for scales. Scales and Arpeggios Major, minor (dorian, natural minor, ascending jazz melodic minor, harmonic minor) and diminished. Resources for jazz scales. IX Equipment Different horns. Mouthpieces. Reeds. Ligatures. Neckstraps. X Resources for saxophonists Recordings. Web resources. Books and educational CD's and DVD's. Saxophonists in jazz and pop music. XI Conclusion. ©2009 Rupe Music Publishing 001 saxophone master class, Jeff Rupert pg2 I Saxophone Assembly and maintenance Neck and mouthpiece assembly: Putting the saxophone together is something we've all been doing since day one. It may seem trite to even address assembly of the instrument, but its been a common flaw not to develop good habits. I've seen broken mouthpieces, bent rods and necks several times from seasoned professionals who should have known better! This is precisely why its important to develop good habits when putting your instrument together. Prior to putting the mouthpiece on the neck, make certain that the cork is lubricated. -

Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Finding Aid Prepared by Audrey Abrams, Simmons GSLIS Intern

Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Finding aid prepared by Audrey Abrams, Simmons GSLIS intern This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit July 31, 2014 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Berklee College Archives 2014/02/11 1140 Boylston St Boston, MA, 02215 617-747-8001 Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Historical note................................................................................................................................................4 Scope and contents........................................................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................4 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 - Page 2 - Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Summary Information Repository Berklee College Archives Creator Berklee College