Characteristics of Rape and Sexual Assault

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

She Is Not a Criminal

SHE IS NOT A CRIMINAL THE IMPACT OF IRELAND’S ABORTION LAW Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: EUR 29/1597/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Stock image: Female patient sitting on a hospital bed. © Corbis amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Executive summary ................................................................................................... 6 -

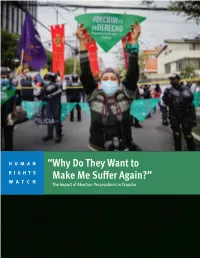

“Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” the Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador

HUMAN “Why Do They Want to RIGHTS WATCH Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 8 To the Presidency ................................................................................................................... -

Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #Metoo

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 49 Issue 1 Article 3 2019 Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #MeToo Nicole Hallett University of Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hallett, Nicole (2019) "Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #MeToo," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 49 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol49/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMMIGRANT WOMEN IN THE SHADOW OF #METOO Nicole Hallett* I. INTRODUCTION We hear Daniela Contreras’s voice, but we do not see her face in the video in which she recounts being raped by an employer at the age of sixteen.1 In the video, one of four released by a #MeToo advocacy group, Daniela speaks in Spanish about the power dynamic that led her to remain silent about her rape: I couldn’t believe that a man would go after a little girl. That a man would take advantage because he knew I wouldn’t say a word because I couldn’t speak the language. Because he knew I needed the money. Because he felt like he had the power. And that is why I kept quiet.2 Daniela’s story is unusual, not because she is an undocumented immigrant who was victimized -

Epic to Novel

EPIC TO NOVEL THOMAS E. MARESCA Epic to Novel OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright® 1974 by the Ohio State University Press All Rights Reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America Portions of the chapter entitled "Dryden11 appeared in the summer 1974 issue ofELH under the title "The Context of Dryden's Absalom and Achitophel." Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Mare sea, Thomas E Epic to Novel Bibliography: p. 1. English fiction — Early modern, 1500-1700 — History and criticism. 2. Epic poetry. English — History and criticism. I. Title. PR769.M3 823\03 74-19109 ISBN 0-8142-0216-0 ISBN 0-8142-0289-6 Original hard-cover edition 3 March 1975 Paperback reprint issued May 1977 FOR DIANE CONTENT S Preface ix Dryden 3 Pope 79 Swift 135 Fielding 181 List of Texts Cited 235 Index 237 PREFACE This book attempts to trace the process by which the novel replaced the epic as the major literary form in English. It explores the hows and whys of this process by an analysis of the subject matter of epic rather than its form or manner; that is, it attempts to find out what post-classical readers understood when they read epic by examination of major commentaries on Virgil's Aeneid from the early Middle Ages through the Renaissance. After that it proceeds to the same goal by close reading of major English literary works that bear a parodic relation to epic. I understand the epic tradition this book talks about as a heterogeneous body of materials growing from a single root, always changing and transforming them selves, but changing in ways and directions indicated by their earliest shaping. -

Economic Incentive of Rape Causes in China ภัยเงียบจากมือที่มองไม่เห็น : เหตุจูงใจทางเศรษฐกิจที่นำ�ไปสู่การข่มขืนในประเทศจีน

8 Intrinsic Control by Invisible Hand : Economic Incentive of Rape Causes in China ภัยเงียบจากมือที่มองไม่เห็น : เหตุจูงใจทางเศรษฐกิจที่น�าไปสู่การข่มขืนในประเทศจีน Shi Qiang ฉื่อ เฉียง วารสารร่มพฤกษ์ มหาวิทยาลัยเกริก 120 ปีที่ 38 ฉบับที่ 1 มกราคม – เมษายน 2563 Intrinsic Control by Invisible Hand : Economic Incentive of Rape Causes in China ภัยเงียบจากมือที่มองไม่เห็น : เหตุจูงใจทางเศรษฐกิจที่น�าไปสู่การข่มขืนในประเทศจีน Shi Qiang1 ฉื่อ เฉียง 1Law Faculty Thammasat University 2 Prachan Road Khwaeng Phra Borommaha Ratchawang Phra Nakhon, Bangkok 10200, Thailand. E-mail : [email protected] 1คณะนิติศาสตร์ มหาวิทยาลัยธรรมศาสตร์ 2 ถนนพระจันทร์ แขวงพระบรมมหาราชวัง เขตพระนคร กรุงเทพมหานคร 10200, ประเทศไทย. E-mail : [email protected] Received : July 8, 2019 Revised : January 19, 2020 Accepted : February 7, 2020 Abstract The objective of this article is to analyze the incentive causes of rape crime with the perspective of economy in China. Utilized and integrated many official Statistics and Reports, states that mainly economic phenomena play the role on rape crimes: During economic migration, peasant workers have aggravated sexual repression, who became a highly concerned potential rape crime group. Under heavy economic burden, delayed marriage age, falling marriage rate and rising divorce rate had led to prolonging asexual period for the young blood. With infections of economic exploitation, the celebrities’ sexual games have diffused imitation effects, while the poor’s sexual helpless will accelerate the social frustration and masculinity loss which cannot compensate the sexual psychology development healthily. This article proposes that lessons from Franz von Liszt’ Criminology Theory, social policy represents the best and effective crime policy, deduces thesolutions including Poverty 8 Alleviation Policy and Reducing Gap in Wealth Policy which maybe reduce the occurrence rate of rape in China. These best economic policies will be able to loosen the hand which halted necks of those souls’ libido. -

Supplementary Information on Kenya, Scheduled for Review by the Pre

Re: Supplementary Information on Kenya, Scheduled for Review by the Pre-sessional Working Group of the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights during its 56th Session Distinguished Committee Members, This letter is intended to supplement the periodic report submitted by the government of Kenya, which is scheduled to be reviewed during the 56th pre-session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (the Committee). The Center for Reproductive Rights (the Center) a global legal advocacy organization with headquarters in New York and, and regional offices in Nairobi, Bogotá, Kathmandu, Geneva, and Washington, D.C., hopes to further the work of the Committee by providing independent information concerning the rights protected under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR),1 and other international and regional human rights instruments which Kenya has ratified.2 The letter provides supplemental information on the following issues of concern regarding the sexual and reproductive rights of Kenyan women and girls: the high rate of preventable maternal mortality and morbidity; the abuse and mistreatment of women that attend maternal health care services; inaccessibility of safe abortion services and post-abortion care; lack of access to comprehensive family planning services and information; and discrimination resulting in gender-based violence and female genital mutilation. I. The Right to Equality and Non-Discrimination It has long been recognized that the obligation to ensure the rights -

Not All Victims of Rape Will Be Recognised As Such in the Eyes of the Law

i International Journal for Intersectional Feminist Studies The Journal of Project Monma Research Centre Volume 2, Issue 1, September2016 ISSN 2463-2945 To cite this social commentary Chi, W. (2016). Not all victims of rape will be recognised as such in the eyes of the law. International Journal for Intersectional Feminist Studies, 2 (1), pp.56-61. International Journal for Intersectional Feminist Studies, Volume 2, Issue 1, September 2016, ISSN 2463-2945 56 Social Commentary: Not all victims of rape will be recognised as such in the eyes of the law Wenluan Chi Abstract This social commentary discusses the contemporary stance of the Chinese government and Chinese society on the issue of marital rape in China. I have focused on this issue from a feminist perspective and the discussion is based mainly on my observations which are based on ideas from a selection of academic readings. When I came to New Zealand to take gender studies courses, I first understood marital rape as a form crime. After this I was able to understand that the marital rape exemption is a reflection of patriarchal legislative system and socio-cultural mores of contemporary Chinese society. Keywords: China, domestic violence, marital rape, violence, women, sexual violence Introduction According to Encyclopedia Dictionary on Roman Law, the word rape originally derived from the Latin verb "rapere", which means "to seize or take by force" (p.667-768). Rape can be defined as a crime in the criminal statutes of most countries and the criminalization of rape under international law (Abegunde, 2013). However, a search of the Statistics New Zealand website reveals that only nine percent of rapes are registered by police. -

Egypt: Situation Report on Violence Against Women

» EGYPT Situation report on Violence against Women 1. Legislative Framework The Egyptian constitution adopted in 2014 makes reference to non-discrimination and equal opportunities (article 9, 11 and 53). Article 11 is the only article that mentions violence against women, stating that: “…The State shall protect women against all forms of violence and ensure enabling women to strike a balance between family duties and work requirements…”. Article 11 states the right of women to political representation as well as equality between men and women in civil, political, economic, social and cultural matters. Article 53 prohibits discrimination on the basis of gender, and makes the state responsible for taking all necessary measures to eliminate all forms of discrimination. Egypt has ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), although with reservations to Article 2 on policy measures and Articles 16 regarding marriage and family life and article 29 . The reservation to Article 9 concerning women’s right to nationality and to pass on their nationality to their children was lifted in 2008. Egypt has signed but not ratified the Rome Statute on the ICC and is not yet a party to the Council of Europe Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women. Articles 267, 268, 269 and 289 of the penal code relating to crimes of rape, sexual assault and harassment fail to address the wave of sexual assault and rape in Egypt following the 2011 revolution. For instance, article 267 of the penal code defines rape as penile penetration of the vagina and does not include rape by fingers, tools or sharp objects, oral or anal rape. -

Intercultural Dialogue on Violence Against Women

3 4 5 Introduction Violence against women and girls is a fundamental violation of human rights, representing one of the most critical public health challenges as well as a major factor hindering development. It is estimated that one in three women worldwide will suffer some form of gender-based violence during the course of her lifetime. Despite efforts from the international community and the commitment by the vast majority of states to combat discrimination against women, notably by means of the ratification of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), women still remain victims of violence and discrimination in all regions of the world. Violence against women takes various forms including domestic violence; rape; trafficking in women and girl; forced prostitution; and violence in armed conflict, such as murder, systematic rape, sexual slavery and forced pregnancy. It also includes honour killings, dowry-related violence, female infanticide, female genital mutilation, and other harmful practices and traditions. “Violence against women is perhaps the most shameful human rights violation. And it is perhaps the most pervasive. It knows no boundaries of geography, culture or wealth. As long as it continues, we cannot claim to be making real progress towards equality, development and peace.” -- Kofi Annan, Secretary General of the United Nations, March 8th, 1999 Violence against women is inextricably linked to unequal gender norms and socio-economic power structures both in the public and private spheres. It serves to reinforce and perpetuate the unequal power relations between women and men. Thus, violence against women is a key issue in addressing gender inequality and discrimination against women as well as in effectively addressing key development issues such as health, poverty, HIV/AIDS, and conflict. -

CHINA a Guide to Keep You Safe Abroad Provided by Sexual Assault Support and Help for Americans Abroad (SASHAA)

Know Before You Go CHINA A Guide to Keep You Safe Abroad Provided by Sexual Assault Support and Help for Americans Abroad (SASHAA) Updated June 2017 KNOW BEFORE YOU GO: CHINA 2 Let’s be perfectly clear, the number one way to prevent sexual assault is to not rape. While the responsibility of ending sexual gender-based violence is on the perpetrators, this guide will offer general safety tips, country-specific information, and resources to help prevent and prepare travelers for the possibility of sexual assault abroad. GENERAL SAFETY TIPS: 1. Use the buddy system and travel with friends! 3 out of 4 2. Be aware of social and cultural norms. For example, looking rapes are at someone in the eyes when you speak to them is perfectly committed normal in the U.S., but in another country that could signify by someone you’re interested in the person. known to the 3. Recognize controlling behavior when entering a relationship. victim1 Most rape survivors recall feeling “uncomfortable” about some of their partner’s behaviors such as degrading jokes/language or refusal to accept “no” as an answer, whether in a sexual context or otherwise.2 4. Avoid secluded places where you could be more vulnerable. Meet new people in public spaces and let a trusted friend know where you’ll be beforehand. 5. Trust your gut. Many victims have a “bad feeling” right before an assault takes place. ALCOHOL AND DRUG AWARENESS: • Always watch your drink being poured and carry it yourself, even to the bathroom. • “Drug-facilitated sexual assault drugs,” also referred to as club drugs or roofies may turn your drink slightly salty, bright blue, or cloudy. -

A Study of Gender Differences of Attitudes Toward Date Rape Among Chinese University Students

Universal Journal of Psychology 6(1): 29-34, 2018 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ujp.2018.060104 A Study of Gender Differences of Attitudes toward Date Rape among Chinese University Students Peitzu Lee*, He Kaiwen, Deng Jiayi Copyright©2018 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The purpose of this study was to investigate likely to interpret people’s intentions with a sexual lens. differences in attitudes towards date rape between genders Also, Muehlenhard [4,7] suggested that men overestimate in Mainland Chinese university students, given the fact that their dates’ sexual interest more often than women do. there is little research about attitudes toward date rape, Moreover, males are less likely to judge the scenarios which is defined as the occurring of forcible intercourse where coercive intercourse take place while dating as date between two parties in romantic or potentially sexual rape compared to females [7,8,9]. relationship, among Chinese people. 104 male and 117 Thus, the Attitudes towards Forcible Date Rape (FDR) female university students, aged from 17 to 27 were asked scale was employed in this study to investigate gender to complete the Attitudes towards Forcible Date Rape differences of male and female’s attitudes toward date rape (FDR) Scale online. The findings showed that female among Chinese college students. The results showed that students rejected date rape-tolerant attitudes more than there were significant gender differences of Chinese their male counterparts. Also, female students expressed students’ attitude toward date rape. -

How to Face Violence Against Women

Step by step HowEMANU to face violence against women ELA 5ªD Cambridge 0 EmanueLiceo Scientifico Statale “Gaetano Salvemini”, Bari Index Preface 1 Violence against women in the past and in the present: spot the differences 2 Women’s voices for change 9 The strange case of misogyny 16 Women: muses in art and objects in real life 22 Violence behind the screen and the musical notes 27 Two pandemics: violence against women and COVID-19 32 Rape culture: the monster in our minds 35 41 Words and bodies: verbal violence and prostitution Conclusion 45 Bibliography 46 1 Preface The idea for this book was born during an English lesson, on an apparently normal Wednesday. However, it was the 25th of November 2020, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against women, and our teacher decided to focus on something which is not included in our school programme. By exchanging our opinions, we understood that our knowledge about the issue was not deep at all, no matter how many newspapers we read or news we watch. That pushed us to start this journey through all the aspects of violence against women. We did it by dividing us into groups and doing several types of research on many different websites and books (you can find our sources on page 46). We discovered that this problem is much wider than what we expected; it has influenced our world in endless ways, affecting all the fields of knowledge, such as art, cinema and music. We ended up reading hundreds of stories that touched us very deeply; that’s how we decided to give life to these pages.