An Historical and Comparative Study of Schools Television in Britain And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Speakers and Chairs 2016

WEDNESDAY 24 FESTIVAL AT A GLANCE 09:30-09:45 10:00-11:00 BREAK BREAK 11:45-12:45 BREAK 13:45-14:45 BREAK 15:30-16:30 BREAK 18:00-19:00 19:00-21:30 20:50-21:45 THE SPEAKERS AND CHAIRS 2016 SA The Rolling BT “Feed The 11:00-11:20 11:00-11:45 P Edinburgh 12:45-13:45 P Meet the 14:45-15:30 P Meet the MK London 2012 16:30-17:00 The MacTaggart ITV Opening Night FH People Hills Chorus Beast” Welcome F Revealed: The T Breakout Does… T Breakout Controller: T Creative Diversity Controller: to Rio 2016: SA Margaritas Lecture: Drinks Reception Just Do Nothing Joanna Abeyie David Brindley Craig Doyle Sara Geater Louise Holmes Alison Kirkham Antony Mayfield Craig Orr Peter Salmon Alan Tyler Breakfast Hottest Trends session: An App Taskmaster session: Charlotte Moore, Network Drinks: Jay Hunt, The Superhumans’ and music Shane Smith The Balmoral screening with Thursday 14.20 - 14.55 Wednesday 15:30-16:30 Thursday 15:00-16:00 Thursday 11:00-11:30 Thursday 09:45-10:45 Wednesday 15:30-16:30 Wednesday 12:50-13:40 Thursday 09:45-10:45 Thursday 10:45-11:30 Wednesday 11:45-12:45 The Tinto The Moorfoot/Kilsyth The Fintry The Tinto The Sidlaw The Fintry The Tinto The Sidlaw The Networking Lounge 10:00-11:30 in TV Formats for Success: Why Branded Content BBC A Little Less Channel 4 Struggle For The Edinburgh Hotel talent Q&A The Pentland Digital is Key in – Big Cash but Conversation, Equality Playhouse F Have I Got F Winning in F Confessions of FH Porridge Adam Abramson Dan Brooke Christiana Ebohon-Green Sam Glynne Alex Horne Thursday 11:30-12:30 Anne Mensah Cathy -

BBC School Radio on CD Primary Guide 2010/2011

BBC School Radio on CD Primary Guide 2010/2011 bbc.co.uk/schoolradio Welcome Welcome to the Guide to BBC School Radio programmes. The Guide includes details of all the series that will be available on CD in the 2010/2011 academic year, as well as details of how to order and information about Teacher’s Notes to support the programmes. Ordering the CDs is simple. You can use the pull-out form in the centre of the Guide or you can phone or fax your order to 0370 977 2727. You can also email your order to [email protected]. The order form can also be printed from the School Radio website at: bbc.co.uk/schoolradio/howtoorder.shtml Please remember to add the cost of postage to your completed order which should be returned to: BBC Schools’ Broadcast Recordings, PO Box 504, Leicester, LE94 0AE Download School Radio programmes In 2010/2011 most School Radio series – including Let’s Move, Time to Move, Something to Think About and Together – will also be available to download as podcasts. Programmes can be downloaded from the School Radio website for 7 days following transmission (or from leading podcast directories, including iTunes). Downloading programmes this way is simple and copies may be kept for as long as you wish. More information here: www.bbc.co.uk/schoolradio/podcasts.shtml Recording programmes off-air Programmes are transmitted overnight on Radio 4 Digital during term time, starting at 0300. A full schedule for each term is available at the School Radio website. Schools are permitted to record and use programmes under the provision of the ERA Act. -

Transforming ITV ITV Plc Report and Accounts 2010 117

ITV plc ITV 2010 accounts and Report ITV plc The London Television Centre Upper Ground London SE1 9LT www.itv.com investors: www.itvplc.com Transforming ITV ITV plc Report and accounts 2010 117 Financial record 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 ITV today Broadcasting & Online ITV Studios £m £m £m £m £m ITV is the largest commercial ITV content is funded by advertising and ITV Studios comprises ITV’s UK production Results Revenue 2,064 1,879 2,029 2,082 2,181 television network in the UK. sponsorship revenues as well as viewer operations, ITV’s international production competitions and voting. ITV1 is the largest companies and ITV Studios Global Earnings before interest, tax and amortisation (EBITA) before exceptional items 408 202 211 311 375 It operates a family of channels commercial channel in the UK. It attracts Entertainment. Amortisation of intangible assets (63) (59) (66) (56) (56) including ITV1, and delivers the largest audience of any UK commercial ITV Studios produces programming for Impairment of intangible assets – – (2,695) (28) (20) broadcaster and has the greatest share of content across multiple platforms ITV’s own channels and for other UK and Share of profits or (losses) of joint ventures and associated undertakings (3) (7) (15) 2 8 the UK television advertising market at via itv.com and ITV Player. international broadcasters. 45.1%. ITV’s digital channels continue to Investment income – – 1 1 3 ITV Studios produces and sells grow their audiences and most recently A wide range of programme genres are Exceptional items 19 (20) (108) (9) 4 programmes and formats in saw the launch of high definition (HD) produced, including: drama, soaps, Profit/(loss) before interest and tax 361 116 (2,672) 221 314 the UK and worldwide. -

Links for Parents Key Stage 2

LINKS TO HOME LEARNING SITES FOR KEY STAGE 2 FREE HOME LEARNING PACKS TO DOWNLOAD https://classroomsecrets.co.uk/free-home-learning-packs/ https://www.hamilton-trust.org.uk/blog/learning-home-packs/ https://collins.co.uk/pages/support-learning-at-home?gclid=EAIaIQobChMImOC7grbJ6AIVxLTtCh10_grpEAMYASAAEgI3_vD_BwE USEFUL SITES TO SEARCH USEFUL SITES Purple Mash HOME SAFETY https://www.nspcc.org.uk/keeping-children-safe/ https://www.purplemash.com/sch/stv-sg1 https://www.redcross.org.uk/first-aid Your child will have a username and password, teachers can provide https://www.childnet.com/resources/looking-for-kidsmart these via email if needed ADAPTING TO THE CURRENT SITUATION https://www.growyourmindset.co.uk/free-resources BBC BITESIZE https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/primary http://www.safehandsthinkingminds.co.uk/covid-anxiety-stress-resources-links/ TOP MARKS https://www.topmarks.co.uk/ https://www.counselorkeri.com/ CRICKWEB http://www.crickweb.co.uk/Key-Stage-2.html THINGS TO DO TOGETHER https://frugalfun4boys.com/ http://www.bbc.co.uk/breathingplaces/natureactivities/ https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/gardening http://puzzlemaker.discoveryeducation.com/ https://butterfly-conservation.org/ http://www.uksafari.com/ RE RE FAITH http://www.togetheratonealtar.catholic.edu.au/ WEDNESDAY WORD http://www.wednesdayword.org/ PRAYER BBC Teach Faiths around the World https://www.tentenresources.co.uk/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=72QaHckhjIw&list=PLcvEcrsF_9zJxDHG9JtcCmiAgwVFRW3uK THE LAST SUPPER BBC BITESIZE https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/subjects/z7hs34j -

Ash Atalla, Probably the Single-Most Successful Comedy Writer-Producer in Britain Right Now

Issue #6 January 2017 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming Gaumont Television presents A new TV Series Visit us during NATPE SEASON 1 : 6 x 52’ at The Fontainebleau Hotel - Chateau #1516 Scripted OFC Jan17.indd 2 19/12/2016 10:56 A TANGLED WORLD BUILT ON BITTER RIVALRIES An ITV & Hulu co-production pIFC-01 ITV Harlots Scripted Jan17.indd 2 19/12/2016 15:54 ITV0030_HarlotsPress_TBIDPS_AW.indd 1 19/12/2016 13:26 A TANGLED WORLD BUILT ON BITTER RIVALRIES An ITV & Hulu co-production pIFC-01 ITV Harlots Scripted Jan17.indd 3 19/12/2016 15:54 ITV0030_HarlotsPress_TBIDPS_AW.indd 1 19/12/2016 13:26 Where Drama Makes It Big. Dial up the drama in a big way with MIPDrama Screenings and MIPTV market 3-6 April 2017 Drama@MIPTV. With more than 2,000 buyers in attendance, the best in World Premiere TV Screenings, and conferences MIPDoc and MIPFormats 1-2 April 2017 exploring the evolution of storytelling, at MIPTV, drama is MIPDrama Screenings 2 April 2017 a big deal. Cannes, FRANCE Registration miptv.com Driving the content economy TBIScriptedp02 drama.indd MIPTV 1 Jan17.indd 1 19/12/201620/12/2016 17:1511:10 In this issue Editor’s Note Often, drama industry journalists follow the money. It’s how we know who’s making what, what’s not going into production and where we think the next hit is coming from. No scripted programme, however, has ever been successful without spending that money on the right creative talent. That’s why in this issue of TBI Scripted, we’re focusing on those creative X 64 types – the writers, creative producers and actors who actually make the programming that audiences love. -

Success and the TV Industry

Success and the TV Industry: How Practitioners Apprehend the Notion(s) of Success in their Discourses within the Anglophone Transatlantic Television Industry Benjamin William Lloyd DERHY KURTZ Submitted for the degree of PhD in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, School of Art, Media and American Studies, (FTM), University of East Anglia 2018 Thesis Defense: 04 December 2017 Examiners: Dr. Catherine Johnson, Dr. Christine Cornea This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Table of Content Abstract i Acknowledgements ii Studying Success in the Television Industry: An Introduction 1 Introduction: 1 I. Settings, Literature Review and Intervention: 6 a. Research Settings: 6 The Television Industry and The Creative / Cultural Industries 6 Creativity 7 Value of Creativity and Labour in the Industry 9 Quality and Legitimacy 11 The Transatlantic Setting 13 Historical and Current Differences between the US and the UK TV Industry 15 Time Frame of the Research within the History of Television 19 Scripted Entertainment and Genre 20 The Five Entities Studied 22 b. Academic Framework and Intervention: 24 The Intersection of Television and Production Studies 25 Academic Work on ‘Success’ 28 Secondary and Tertiary Fields of Engagement 30 II. Research Questions and Structure of the Thesis: 34 a. Main Research Questions: 34 b. Thesis Structure: 36 Conclusion: 40 I. Reflections on Methodological Approaches and on the Industry 42 Introduction: 42 I. -

Nima Elbagir: Life on the Frontline Size Matters a Provocative Look at Short-Form Content

June 2016 Nima Elbagir: Life on the frontline Size matters A provocative look at short-form content Pat Younge CEO, Sugar Films (Chair) Randel Bryan Director of Content and Strategy UK, Endemol Shine Beyond UK Adam Gee Commissioning Editor, Multi-platform and Online Video (Factual), Channel 4 Max Gogarty Daily Content Editor, BBC Three Kelly Sweeney Director of Production/Studios, Maker Studios International Andy Taylor CEO, Little Dot Studios Steve Wheen CEO, The Distillery 4 July The Hospital Club, 24 Endell Street, London WC2H 9HQ Booking: www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society June 2016 l Volume 53/6 From the CEO The third annual RTS/ surroundings of the Oran Mor audito- Mockridge, CEO of Virgin Media; Cathy IET Joint Public Lec- rium in Glasgow. Congratulations to Newman, Presenter of Channel 4 News; ture, held in the all the winners. and Sharon White, CEO of Ofcom. unmatched surround- Back in London, RTS Futures held Steve Burke, CEO of NBCUniversal, ings of London’s Brit- an intimate workshop in the board- will deliver the opening keynote. ish Museum, was a room here at Dorset Rise: 14 industry An early-bird rate is available for night to remember. I newbies were treated to tips on how those of you who book a place before was thrilled to see such a big turnout. to secure work in the TV sector. June 30 – just go to the RTS website: Nobel laureate Sir Paul Nurse gave a Bookings are now open for the RTS’s rts.org.uk/event/rts-london-conference-2016. -

BBC School Radio on CD Primary Guide 2011/2012 Bbc.Co.Uk/Schoolradio Welcome Welcome to the New Guide to BBC School Radio Resources

BBC School Radio on CD Primary Guide 2011/2012 bbc.co.uk/schoolradio Welcome Welcome to the new Guide to BBC School Radio resources. The Guide includes details of all the series that will be available on CD in the 2011/2012 academic year, as well as details of how to order and information about Teacher’s Notes to support the programmes. It also includes important information about new School Radio resources that are available online. Ordering the CDs is simple. You can use the pull-out form in the centre of the Guide or you can phone or fax your order to 0370 977 2727. You can also email your order to [email protected]. The order form can also be printed from the School Radio website at: bbc.co.uk/schoolradio/ordercd Please remember to add the cost of postage to your completed order which should be returned to: BBC Schools’ Broadcast Recordings, PO Box 504, Leicester, LE94 0AE Download School Radio programmes In 2011/2012 most School Radio series – including Let’s Move, Time to Move, Something to Think About and Together – will also be available to download as podcasts. Programmes can be downloaded for 30 days following transmission, can be shared with your classes without restriction and may be kept for as long as you wish. More information here: bbc.co.uk/schoolradio/podcasts Recording programmes off-air Programmes are transmitted overnight on Radio 4 Digital during term time, starting at 0300. A full schedule for each term is available at the School Radio website. -

The Class of 2018 CAREERSTV Fair

January 2018 The class of 2018 CAREERSTV Fair 6 February 10:00am-4:00pm Business Design Centre, London N1 0QH Journal of The Royal Television Society January 2018 l Volume 55/1 From the CEO Welcome to 2018. In With luck, some of these industry Hector, who recalls a very special this issue of Television leaders will be joining RTS events in evening in Bristol when a certain we have assembled the coming months, so we can hear 91-year-old natural history presenter a line-up of features from them directly. was, not for the first time, the centre that reflects the new Following the excesses – and per- of attention. Did anyone mention TV landscape and haps stresses – of Christmas, our Janu- Blue Planet II? its stellar class of 2018. ary edition contains what I hope read- Our industry map looks like it’s Pictured on this month’s cover are ers will agree is some much-needed being redrawn dramatically. Disney’s some of the sector’s leaders who are light relief. Don’t miss Kenton Allen’s historic $52.4bn bid for 21st Century certain to be making a big splash in pulsating review of 2017. I guarantee Fox is among a number of moves the year ahead – Tim Davie, Ian Katz, that it’s laugh-out-loud funny. responding to the need for scale. We Jay Hunt, Carolyn McCall, Alex Mahon, Also bringing a light touch to this will be looking at this trend in the Simon Pitts and Fran Unsworth. month’s Television is Stefan Stern’s coming months. -

School Radio 2014-2015

Early Learningarninarnininngg Mathematics Dance HistoryHistorHiHHistoHiststoryoryryy PPHSEP Geography Englishshh aandndd DramDraDramaDrDramamamaa AsseAssembliesm CollectiveColleCollectiCollecCCoollectivelectiveectivetivevee WWorkWWorkshopskshok opss CitizenshipCCitizeCitizCitCitizensitizenshzenshienshinshih p MMusics Early Learning Mathematics DanceDDanDanceancece History PHSE Geography Englishh anda Drama Assembliesbbc.co.uk/learning/schoolradiobbc.co.ubbc CollectiveCCollective Workshopsorks CitizenshipCCittizeen p MMuMusic BBC School Radio Primary Guide 2014 - 2015 bbc.co.uk/learning/schoolradio bbc.co.uk/learning/schoolradio 1 Welcome Welcome to BBC School Radio resources for 2014/2015. In this short guide you’ll be able to find out about programmes in the coming year and how to acquire them. The guide also includes information about some recent additions to the School Radio website. In 2014 – 2015 all programmes will be available to download Over the last few years we have been able to significantly increase the availability of programmes to download from the website and trust that schools will now feel able to make the transition from ordering CDs to downloading the resources. If you are new to downloading programmes please read the following section carefully. We welcome your feedback. You can email us directly at: [email protected] or you can write to us at: BBC School Radio, 3rd Floor Bridge House, MediaCityUK, Manchester M50 2BH Contents How to download School Radio programmes 3 Recent additions 4 Programmes commemorating WW1 5 Early Learning 6 English and Drama 7 Dance 8 Music 9-10 Assemblies / Collective Worship 11 History 12 PHSE / PSD and Citizenship 13 Scotland 13 Computing 14 2 bbc.co.uk/learning/schoolradio How to download School Radio programmes In 2014 – 2015 all School Radio programmes will be available to download for a limited period of time. -

Changes in the Teaching of Folk and Traditional Music: Folkworks and Predecessors

Changes in the Teaching of Folk and Traditional Music: Folkworks and Predecessors Thesis M. Price Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD Newcastle University November 2017 i Abstract Formalised folk music education in Britain has received little academic attention, despite having been an integral part of folk music practice since the early 1900s. This thesis explores the major turns, trends and ideological standpoints that have arisen over more than a century of institutionalised folk music pedagogy. Using historical sources, interviews and observation, the thesis examines the impact of the two main periods of folk revival in the UK, examining the underlying beliefs and ideological agendas of influential figures and organisations, and the legacies and challenges they left for later educators in the field. Beginning with the first revival of the early 1900s, the thesis examines how the initial collaboration and later conflict between music teacher and folk song collector Cecil Sharp, and social worker and missionary Mary Neal, laid down the foundations of folk music education that would stand for half a century. A discussion of the inter-war period follows, tracing the impact of wireless broadcasting technology and competitive music festivals, and the possibilities they presented for both music education and folk music practice. The second, post-war revival’s dominance by a radical leftwing political agenda led to profound changes in pedagogical stance; the rejections of prior practice models are examined with particular regard to new approaches to folk music in schools. Finally, the thesis assesses the ways in which Folkworks and their contemporaries in the late 1980s and onward were able to both adapt and improve upon previous approaches. -

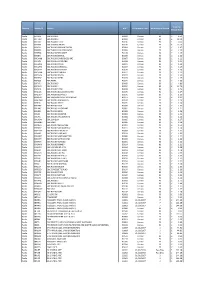

Domain Station ID Station UDC Performance Date No of Days in Period Total Per Minute Rate Radio BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 B0001 Census

Total Per Domain Station ID Station UDC Performance Date No of Days in Period Minute Rate Radio BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 B0001 Census 90 £ 4.51 Radio BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 B0002 Census 90 £ 18.00 Radio BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA B0106 Census 90 £ 0.60 Radio BR4DIG BBC SCHOOL RADIO B0109 Census 90 £ 13.70 Radio BRASIA BBC RADIO ASIAN NETWORK B0064 Census 90 £ 1.47 Radio BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO B0065 Census 90 £ 1.25 Radio BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE B0103 Census 90 £ 1.19 Radio BRBRIS BBC RADIO BRISTOL B0066 Census 90 £ 1.16 Radio BRCAMB BBC RADIO CAMBRIDGESHIRE B0067 Census 90 £ 1.22 Radio BRCLEV BBC RADIO CLEVELAND B0068 Census 90 £ 1.22 Radio BRCMRU BBC RADIO CYMRU B0011 Census 90 £ 1.24 Radio BRCORN BBC RADIO CORNWALL B0069 Census 90 £ 1.29 Radio BRCOVN BBC RADIO COVENTRY B0070 Census 90 £ 1.18 Radio BRCUMB BBC RADIO CUMBRIA B0071 Census 90 £ 1.23 Radio BRDEVN BBC RADIO DEVON B0072 Census 90 £ 1.30 Radio BRDRBY BBC RADIO DERBY B0073 Census 90 £ 1.25 Radio BRESSX BBC ESSEX B0074 Census 90 £ 1.36 Radio BRFIVE BBC RADIO 5 B0005 Census 90 £ 4.89 Radio BRFOUR BBC RADIO 4 B0004 Census 90 £ 13.70 Radio BRFOYL BBC RADIO FOYLE B0019 Census 90 £ 1.76 Radio BRGLOS BBC RADIO GLOUCESTERSHIRE B0075 Census 90 £ 1.17 Radio BRGUER BBC RADIO GUERNSEY B0076 Census 90 £ 1.13 Radio BRHRWC BBC HEREFORD AND WORCESTER B0077 Census 90 £ 1.21 Radio BRHUMB BBC RADIO HUMBERSIDE B0078 Census 90 £ 1.29 Radio BRJERS BBC RADIO JERSEY B0079 Census 90 £ 1.14 Radio BRKENT BBC RADIO KENT B0080 Census 90 £ 1.32 Radio BRLANC BBC RADIO LANCASHIRE B0081 Census 90 £ 1.21 Radio