Cried the Balladeer: the Concept Musical Defined

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

The-Music-Of-Andrew-Lloyd-Webber Programme.Pdf

Photograph: Yash Rao We’re thrilled to welcome you safely back to Curve for production, in particular Team Curve and Associate this very special Made at Curve concert production of Director Lee Proud, who has been instrumental in The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber. bringing this show to life. Over the course of his astonishing career, Andrew It’s a joy to welcome Curve Youth and Community has brought to life countless incredible characters Company (CYCC) members back to our stage. Young and stories with his thrilling music, bringing the joy of people are the beating heart of Curve and after such MUSIC BY theatre to millions of people across the world. In the a long time away from the building, it’s wonderful to ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER last 15 months, Andrew has been at the forefront of have them back and part of this production. Guiding conversations surrounding the importance of theatre, our young ensemble with movement direction is our fighting for the survival of our industry and we are Curve Associate Mel Knott and we’re also thrilled CYCC LYRICS BY indebted to him for his tireless advocacy and also for alumna Alyshia Dhakk joins us to perform Pie Jesu, in TIM RICE, DON BLACK, CHARLES HART, CHRISTOPHER HAMPTON, this gift of a show, celebrating musical theatre, artists memory of all those we have lost to the pandemic. GLENN SLATER, DAVID ZIPPEL, RICHARD STILGOE AND JIM STEINMAN and our brilliant, resilient city. Known for its longstanding Through reopening our theatre we are not only able to appreciation of musicals, Leicester plays a key role make live work once more and employ 100s of freelance in this production through Andrew’s pre-recorded DIRECTED BY theatre workers, but we are also able to play an active scenes, filmed on-location in and around Curve by our role in helping our city begin to recover from the impact NIKOLAI FOSTER colleagues at Crosscut Media. -

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. -

The American Film Musical and the Place(Less)Ness of Entertainment: Cabaret’S “International Sensation” and American Identity in Crisis

humanities Article The American Film Musical and the Place(less)ness of Entertainment: Cabaret’s “International Sensation” and American Identity in Crisis Florian Zitzelsberger English and American Literary Studies, Universität Passau, 94032 Passau, Germany; fl[email protected] Received: 20 March 2019; Accepted: 14 May 2019; Published: 19 May 2019 Abstract: This article looks at cosmopolitanism in the American film musical through the lens of the genre’s self-reflexivity. By incorporating musical numbers into its narrative, the musical mirrors the entertainment industry mise en abyme, and establishes an intrinsic link to America through the act of (cultural) performance. Drawing on Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope and its recent application to the genre of the musical, I read the implicitly spatial backstage/stage duality overlaying narrative and number—the musical’s dual registers—as a means of challenging representations of Americanness, nationhood, and belonging. The incongruities arising from the segmentation into dual registers, realms complying with their own rules, destabilize the narrative structure of the musical and, as such, put the semantic differences between narrative and number into critical focus. A close reading of the 1972 film Cabaret, whose narrative is set in 1931 Berlin, shows that the cosmopolitanism of the American film musical lies in this juxtaposition of non-American and American (at least connotatively) spaces and the self-reflexive interweaving of their associated registers and narrative levels. If metalepsis designates the transgression of (onto)logically separate syntactic units of film, then it also symbolically constitutes a transgression and rejection of national boundaries. In the case of Cabaret, such incongruities and transgressions eventually undermine the notion of a stable American identity, exposing the American Dream as an illusion produced by the inherent heteronormativity of the entertainment industry. -

Feminisms 1..277

Feminisms The Key Debates Mutations and Appropriations in European Film Studies Series Editors Ian Christie, Dominique Chateau, Annie van den Oever Feminisms Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures Edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover design: Neon, design and communications | Sabine Mannel Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 676 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 363 4 doi 10.5117/9789089646767 nur 670 © L. Mulvey, A. Backman Rogers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Editorial 9 Preface 10 Acknowledgments 15 Introduction: 1970s Feminist Film Theory and the Obsolescent Object 17 Laura Mulvey PART I New Perspectives: Images and the Female Body Disconnected Heroines, Icy Intelligence: Reframing Feminism(s) and Feminist Identities at the Borders Involving the Isolated Female TV Detective in Scandinavian-Noir 29 Janet McCabe Lena Dunham’s Girls: Can-Do Girls, -

KS5 Exploring Performance Styles in Musical Theatre

Exploring performance KS5 styles in Musical Theatre Heidi McEntee Heidi McEntee is a Dance and KS5 – BTEC LEVEL 3, UNIT D10 Performing Arts specialist based in the Midlands. She has worked in education for over fifteen years delivering a variety of Dance and Performing Arts qualifications at Introduction Levels 1, 2 and 3. She is a Senior Unit D10: Exploring Performance Styles is one of the three units which sit within Module D: Assessment Associate working on musical theatre Skills Development from the new BTEC Level 3 in Performing Arts Practice Performing Arts qualifications and (musical theatre) qualification. This scheme of work focuses on the first unit which introduces a contributing author for student and explores different musical theatre styles. revision guides. This unit requires learners to develop their practical skills in dance, acting and singing while furthering their understanding of musical theatre styles. The unit culminates in a performance of two extracts in two different styles of musical theatre as well as a critical review of the stylistic qualities within these extracts. This scheme of work provides a suggested approach to six weeks of introductory classes, as a part of a full timetable, which explores the development of performance styles through the history of musical theatre via practical activities, short projects and research tasks. Learning objectives By the end of this scheme, learners will have: § Investigated the history of musical theatre and the factors which have influenced its development Unit D10: Exploring Performance § Explored the characteristics of different musical theatre styles and how they have developed Styles from BTEC L3 Nationals over time Performing Arts Practice (musical § Applied stylistic conventions to the performance of material theatre) (2019) § Examined professional work through critical analysis. -

Marvin Hamlisch

tHE iRA AND lEONORE gERSHWIN fUND IN THE lIBRARY OF cONGRESS AN EVENING WITH THE MUSIC OF MARVIN HAMLISCH Monday, October 19, 2015 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building The Ira and Leonore Gershwin Fund in the Library of Congress was established in 1992 by a bequest from Mrs. Gershwin to perpetuate the name and works of her husband, Ira, and his brother, George, and to provide support for worthy related music and literary projects. "LIKE" us at facebook.com/libraryofcongressperformingarts loc.gov/concerts Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Monday, October 19, 2015 — 8 pm tHE iRA AND lEONORE gERSHWIN fUND IN THE lIBRARY OF cONGRESS AN EVENING WITH THE mUSIC OF MARVIN hAMLISCH WHITNEY BASHOR, VOCALIST | CAPATHIA JENKINS, VOCALIST LINDSAY MENDEZ, VOCALIST | BRYCE PINKHAM, VOCALIST -

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

Leonard Bernstein's MASS

27 Season 2014-2015 Thursday, April 30, at 8:00 Friday, May 1, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, May 2, at 8:00 Sunday, May 3, at 2:00 Leonard Bernstein’s MASS: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers* Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin Texts from the liturgy of the Roman Mass Additional texts by Stephen Schwartz and Leonard Bernstein For a list of performing and creative artists please turn to page 30. *First complete Philadelphia Orchestra performances This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes, and will be performed without an intermission. These performances are made possible in part by the generous support of the William Penn Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Additional support has been provided by the Presser Foundation. 28 I. Devotions before Mass 1. Antiphon: Kyrie eleison 2. Hymn and Psalm: “A Simple Song” 3. Responsory: Alleluia II. First Introit (Rondo) 1. Prefatory Prayers 2. Thrice-Triple Canon: Dominus vobiscum III. Second Introit 1. In nomine Patris 2. Prayer for the Congregation (Chorale: “Almighty Father”) 3. Epiphany IV. Confession 1. Confiteor 2. Trope: “I Don’t Know” 3. Trope: “Easy” V. Meditation No. 1 VI. Gloria 1. Gloria tibi 2. Gloria in excelsis 3. Trope: “Half of the People” 4. Trope: “Thank You” VII. Mediation No. 2 VIII. Epistle: “The Word of the Lord” IX. Gospel-Sermon: “God Said” X. Credo 1. Credo in unum Deum 2. Trope: “Non Credo” 3. Trope: “Hurry” 4. Trope: “World without End” 5. Trope: “I Believe in God” XI. Meditation No. 3 (De profundis, part 1) XII. -

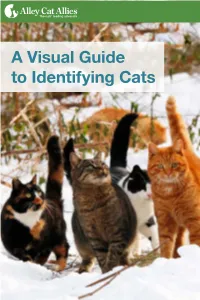

A Visual Guide to Identifying Cats

A Visual Guide to Identifying Cats When cats have similar colors and patterns, like two gray tabbies, it can seem impossible to tell them apart! That is, until you take note of even the smallest details in their appearance. Knowledge is power, whether you’re an animal control officer or animal Coat Length shelter employee who needs to identify cats regularly, or you want to identify your own cat. This guide covers cats’ traits from their overall looks, like coat pattern, to their tiniest features, like whisker color. Let’s use our office cats as examples: • Oliver (left): neutered male, shorthair, solid black, pale green eyes, black Hairless whiskers, a black nose, and black Hairless cats have no fur. paw pads. • Charles (right): neutered male, shorthair, brown mackerel tabby with spots toward his rear, yellow-green eyes, white whiskers with some black at the roots, a pink-brown nose, and black paw pads. Shorthair Shorthair cats have short fur across As you go through this guide, remember that certain patterns and markings the entire body. originated with specific breeds. However, these traits now appear in many cats because of random mating. This guide covers the following features: Coat Length ...............................................................................................3 Medium hair Coat Color ...................................................................................................4 Medium hair cats have longer fur around the mane, tail, and/or rear. Coat Patterns ..............................................................................................6 -

Musical! Theatre!

Premier Sponsors: Sound Designer Video Producer Costume Coordinator Lance Perl Chrissy Guest Megan Rutherford Production Stage Manager Assistant Stage Manager Stage Management Apprentice Mackenzie Trowbridge* Kat Taylor Lyndsey Connolly Production Manager Dramaturg Assistant Director Adam Zonder Hollyann Bucci Jacob Ettkin Musical Director Daniel M. Lincoln Directors Gerry McIntyre+ & Michael Barakiva+ We wish to express our gratitude to the Performers’ Unions: ACTORS’ EQUITY ASSOCIATION AMERICAN GUILD OF MUSICAL ARTISTS AMERICAN GUILD OF VARIETY ARTISTS SAG-AFTRA through Theatre Authority, Inc. for their cooperation in permitting the Artists to appear on this program. * Member of the Actor's Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. + ALEXA CEPEDA is delighted to be back at The KRIS COLEMAN* is thrilled to return to the Hangar. Hangar! Select credits: Mamma Mia (CFRT), A Broadway Credit: Jersey Boys (Barry Belson) Chorus Line (RTP), In The Heights (The Hangar Regional Credit: Passing Strange (Narrator), Jersey Theatre), The Fantasticks (Skinner Boys - Las Vegas (Barry Belson), Chicago (Hangar Barn), Cabaret (The Long Center), Anna in the Theatre, Billy Flynn), Dreamgirls (Jimmy Early), Sister Tropics (Richard M Clark Theatre). She is the Act (TJ), Once on This Island (Agwe), A Midsummer founder & host of Broadway Treats, an annual Nights Dream (Oberon) and Big River (Jim). benefit concert organized to raise funds for Television and film credits include: The Big House Animal Lighthouse Rescue (coming up! 9/20/20), and is (ABC), Dumbbomb Affair, and The Clone. "As we find ourselves currently working on her two-person musical Room 123. working through a global pandemic and race for equality, work Proud Ithaca College BFA alum! "Gracias a mamacita y papi." like this shows the value and appreciation for all.