Detached Fragments of Humanity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-2020 Annual Report and Financial Statements

ANNUAL REPORT and FINANCIAL STATEMENTS - for the year ended 31 MARCH 2020 STATEMENTS REPORT and FINANCIAL ANNUAL The Museum, 41 Long Street, Devizes, Wiltshire. SN10 1NS Telephone: 01380 727369 www.wiltshiremuseum.org.uk Our Audiences Our audiences are essential and work is ongoing, with funding through the Wessex Museums Partnership, to understand our audiences and develop projects and facilities to ensure they remain at the core of our activities. Our audience includes visitors, Society members, school groups, community groups, and researchers. Above: testimonial given in February 2020 by one of our visitors. Below: ‘word cloud’ comprising the three words used to describe the Museum on the audience forms during 2019/20. Cover: ‘Chieftain 1’ by Ann-Marie James© Displayed in ‘Alchemy: Artefacts Reimagined’, an exhibition of contemporary artworks by Ann-Marie James. Displayed at Wiltshire Museum May-August 2020. (A company limited by guarantee) Charity Number 1080096 Company Registration Number 3885649 SUMMARY and OBJECTS The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Researchers. Every year academic researchers Society (the Society) was founded in 1853. The carry out important research on the collection. Society’s first permanent Museum opened in There are over 500,000 items in the collections Long Street in 1874. The Society is a registered and details can be found in our online searchable charity and governed by Articles of Association. database. The collections are ‘Designated’ of national importance and ‘Accreditation’ status Objects. To educate the public by promoting, was first awarded in 2005. Overseen by the fostering interest in, exploration, research and Arts Council the Accreditation Scheme sets publication on the archaeology, art, history and out nationally-agreed standards, which inspire natural history of Wiltshire for the public benefit. -

A Village Site of the Hallstatt Period in Wiltshire

A Village Site of the Hallstatt Period in Wiltshire By MRS. M. E. CUNNINGTON THE site of an Early Iron Age village on All Cannings Cross Farm, about six miles east of Devizes, was discovered quite by chance. In this corn-growing country great open ploughed fields fringe the lower slopes of the high chalk downs. At All Cannings Cross the ploughed land stretches to the foot of Tan Hill and Clifford's Hill, on the Marlborough Downs, overlooking the vale of Pewsey. The site of the settlement has been under plough for many years, perhaps for centuries, so that any surface indications there may once have been, have long since dis- appeared. Our attention was first drawn to the spot by the unusual number of the rough implements known as ' hammerstones' that were strewn over the ploughed surface. It looked as if some special local industry in which these stones were used had been carried on there, and in 1911 we cut a few trenches to test the site. We found a considerable quantity of pottery, bones, etc., and a few fragments of bronze and iron. A short account of this was published in the Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine, vol. xxxvii, p. 526. The site was not touched again until the autumn of 1920, when a small area was examined. The extent of the settle- ment is not known, but to judge from the distribution of the hammerstones over the surface it probably covers several acres. From first to last no evidence has been found to show what the hammerstones of flint and sarsen were used for ; it seems that they must have been used in dressing stone for some purpose, perhaps in making querns and mealing stones out of the sarsen boulders that occur naturally on these Downs. -

Archaeological Research Agenda for the Avebury World Heritage Site

This volume draws together contributions from a number of specialists to provide an agenda for future research within the Avebury World Heritage Site. It has been produced in response to the English Heritage initiative for the development of regional and period research frameworks in England and represents the first formal such agenda for a World Heritage Site. Following an introduction setting out the background to, need for and development of the Research Agenda, the volume is presented under a series of major headings. Part 2 is a resource assessment arranged by period from the Lower Palaeolithic to the end of the medieval period (c. AD 1500) together with an assessment of the palaeo-environmental data from the area. Part 3 is the Research Agenda itself, again arranged by period but focusing on a variety of common themes. A series of more over-arching, landscape-based themes for environmental research is also included. In Part 4 strategies for the implementation of the Research Agenda are explored and in Part 5 methods relevant for that implementation are presented. Archaeological Research Agenda for the Avebury World Heritage Site Avebury Archaeological & Historical Research Group (AAHRG) February 2001 Published 2001 by the Trust for Wessex Archaeology Ltd Portway House, Old Sarum Park, Salisbury SP4 6EB Wessex Archaeology is a Registered Charity No. 287786 on behalf of English Heritage and the Avebury Archaeological & Historical Research Group Copyright © The individual authors and English Heritage all rights reserved British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 1–874350–36–1 Produced by Wessex Archaeology Printed by Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge The cost of this publication was met by English Heritage Front Cover: Avebury: stones at sunrise (© English Heritage Photographic Library. -

Worth Matravers Archaeology Project

BRITISH ARCHAEOLOGICAL AWARDS Submission for BEST COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY PROJECT WORTH MATRAVERS ARCHAEOLOGY PROJECT Submitted by Lilian Ladle and Andrew Morgan on behalf of EAST DORSET ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY February 2012 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 3 1.1. PROJECT .......................................................................................................................... 3 1.2. OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.3. EAST DORSET ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY ........................................................................... 3 1.4. THE SITE ......................................................................................................................... 3 1.5. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................. 4 2. THE EXCAVATION......................................................................................................... 4 3. ARCHAEOLOGY IN THE COMMUNITY ..................................................................... 7 4. CONTRIBUTION TO ARCHAEOLOGY IN UK ............................................................ 8 5. POST EXCAVATION AND PUBLICATION ................................................................. 8 5.1. RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES .......................................................................................... -

The Prehistoric Society

THE PREHISTORIC SOCIETY UK STUDY TOUR 2007: WILTSHIRE Monday 20th August – Friday 24th August 2007 Urchfont Manor, Urchfont, Devizes, Wiltshire, SN10 4RG, Tel. no. 01380 840495 www.urchfontmanor.co.uk This study tour will be based at Urchfont Manor in the Vale of Pewsey, located in the heart of Wiltshire. It is a scenic, peaceful, location for our Study Tour and provides us with easy access to some of the most outstanding prehistoric sites and landscapes in the British Isles. During the tour we will encounter a wide range of well preserved sites on the chalk downland that lies at the heart of Wiltshire, focussing specifically on the Avebury and Stonehenge World Heritage Site. As well as this we are fortunate to gain access to normally restricted areas on the Salisbury Plain military ranges. All of these areas have either seen recent investigation or are currently the subject of major, internationally significant, research. So, as well as the monumental complex at Avebury, we will visit the high profile work taking place at Stonehenge and Durrington Walls and include an evening visit to the ‘stones’. The tour will be rounded off in the Wylye Valley of South Wiltshire, an important routeway flanked by a variety of significant archaeological sites. Urchfont Manor, though in a rural position is easily reachable by car, lying some 3km to the south-east of the market town of Devizes at NGR SU 036570 just off the A342. There are relatively nearby train stations at Pewsey and Westbury; it may well be possible to arrange a pick up for those travelling by train. -

3. the Later Prehistoric Pottery by Lisa Brown

Excavations at Segsbury Camp: The Later Prehistoric Pottery 3. The Later Prehistoric Pottery by Lisa Brown 3.1 Introduction The excavations produced a total of 3278 sherds of later prehistoric pottery weighing 18814g. A small collection of thirty, mostly unstratified, early Roman sherds, was also recovered. The condition of the assemblage is generally extremely poor, most sherds being highly abraded and fragmentary. A small number are so small (below one gram in weight) that their fabric type was not identifiable. It was, nonetheless, possible to establish a chronological sequence and a broad typology of fabrics and vessel forms on the basis of a small number of distinctive sherds. The majority of classifiable sherds are of Early Iron Age type (7th-4th centuries BC), the remainder belonging to the Middle Iron Age (4th-2nd centuries BC). Most of the assemblage (55%) derived from pit fills, and it was from these deposits that the few large sherds in good or fair condition were recovered. The remainder of sherds were recovered from ditch fills (12%), a variety of small features (4%), layers relating to the rampart (5%), or were unstratified within the topsoil (24%). 3.2 Method All sherds were recorded to the same level of detail. The pottery was examined with the aid of a binocular microscope (x 20) and a hand lens (x 10 and x 20). The pottery was characterised by fabric, form, surface treatment, decoration, number and weight of sherds. Degree of abrasion was recorded on a scale of 1 to 3 (1 being the freshest) and the presence of carbonised residue, soot and limescale was noted, although residues were rarely preserved. -

PDF (Volume 2)

Durham E-Theses Landscape, settlement and society: Wiltshire in the rst millennium AD Draper, Simon Andrew How to cite: Draper, Simon Andrew (2004) Landscape, settlement and society: Wiltshire in the rst millennium AD, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Landscape, Settlement and Society: Wiltshire in the First Millennium AD VOLUME 2 (OF 2) By Simon Andrew Draper A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted in 2004 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Durham, following research conducted in the DepartA Archaeology ~ 2 1 JUN 2005 Table of Contents VOLUME2 Appendix 1 page 222 Appendix 2 242 Tables and Figures 310 222 AlPPlENIDRX 11 A GAZEITEER OF ROMANo-BRliTISH §EITLlEMENT SiTES TN WTLTSHm.lE This gazetteer is based primarily on information contained in the paper version of the Wiltshire Sites and Monuments Record, which can be found in Wiltshire County Council's Archaeology Office in Trowbridge. -

WILTSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL and NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY (Company Limited by Guarantee)

ANNUAL REPORT and FINANCIAL STATEMENTS - for the year ended 31 MARCH 2018 STATEMENTS REPORT and FINANCIAL ANNUAL WILTSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY (Company Limited by Guarantee) The Museum, 41 Long Street, Devizes, Wiltshire. SN10 1NS Telephone: 01380 727369 www.wiltshiremuseum.org.uk Framed pen and watercolour pencil drawing of Wadworth Brewery, Devizes by Samuel Croft ©. Winner of the Oexmann Purchase Prize 2017. (A company limited by guarantee) Charity Number 1080096 Company Registration Number 3885649 SUMMARY and OBJECTS The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History The collections were ‘Designated’ of national Society (the Society, aka WANHS – pronounced importance in 1999 and the Museum was ‘wans’) was founded in 1853. The Society’s first awarded ‘Accreditation’ status in 2005, which was permanent Museum opened in Long Street in renewed in 2015. Overseen by the Arts Council 1874. the ‘Accreditation Scheme sets out nationally- agreed standards, which inspire the confidence The Society is a registered charity and of the public and funding and governing bodies. governed by Articles of Association (available It enables museums to assess their current on request). Its objects are ‘to explore the performance, as well as supporting them to plan archaeology, art, history and natural history and develop their services’. of Wiltshire’. To achieve these aims we run the Wiltshire Museum, organise a programme The Library is open for research and contains of conferences, lecture and events, run a a local studies collection of books, journals, learning and outreach programme for children newspapers and other printed items including and schools, provide access to our objects, photographs and maps concerned with Wiltshire. -

The Wessex Hillforts Project

Bibliography Ainsworth, S, Oswald, A and Pearson, T 2001 ‘Discovering Our FSA. Cambridge Hillfort Heritage’, PAST (The Newsletter of the Prehistoric Society), — 1998 Barbury ‘Castle: an Archaeological Survey by the Royal 39, November 2001, 3-4 Commission on the Historical Monuments of England’. RCHME Aitken, M J 1974 Physics and Archaeology, 2 edn. Oxford: Clarendon Survey Report, AI/3/1998 Press — (ed) 1999 Unravelling the Landscape, an Inquisitive Approach to Aitken. M J and Tite, M S 1962 ‘Proton magnetometer surveying on Archaeology. Stroud: Tempus some British hill-forts’, Archaeometry, 5, 126–34 — 2000 Liddington Castle Archaeological Earthwork Survey. English Alcock, L 1968a ‘Cadbury Castle’, 1967, Antiquity, 42, 47–51 Heritage survey report, AI/4/2001 — 1968b ‘Excavations at South Cadbury Castle, 1967, a summary Bowden, M 2005 ‘The Middle Iron Age on the Marlborough report’, Antiq J, 48, 6–17 Downs’, in Brown, G, Field, D and McOmish, D (eds) — 1969 ‘Excavations at South Cadbury Castle, 1968, a summary The Avebury Landscape – Aspects of the Field Archaeology of the report’, Antiq J, 49, 30–40 Marlborough Downs. Oxbow Books, Oxford, 156-63 — 1970 ‘South Cadbury Excavations, 1969’, Antiquity, 44, 46–9 Bowden, M, Ford, S and Gaffney, V 1993 ‘The excavation of a Late — 1971 ‘Excavations at South Cadbury Castle, 1970, summary Bronze Age artefact scatter on Weathercock Hill’, Berkshire report’, Antiq J, 51, 1–7 Archaeol J, 74, 69–83 — 1972 ‘By South Cadbury is that Camelot…’ Excavations at Cadbury Bowden, M and McOmish, D 1987 ‘The Required Barrier’, Scottish Castle 1966–1970. London Archaeol Rev, 4, 76–84 — 1980 ‘The Cadbury Castle sequence in the first millennium BC’, — 1989 ‘Little Boxes: more about hillforts’, Scottish Archaeol Rev, 6, Bull Board Celtic Stud, 28, 656–718 12–16 — 1995 Cadbury Castle, Somerset: the Early Medieval Archaeology. -

2018 Histories of Deposition

Histories of Deposition: Creating Chronologies for the Late Bronze Age- ANGOR UNIVERSITY Early Iron Age transition in southern Britain Waddington, Kate; Alex, Bayliss; Higham, Thomas; Madgwick, Richard; Sharples, Niall Archaeological Journal DOI: 10.1080/00665983.2018.1504859 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 01/01/2019 Peer reviewed version Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Waddington, K., Alex, B., Higham, T., Madgwick, R., & Sharples, N. (2019). Histories of Deposition: Creating Chronologies for the Late Bronze Age-Early Iron Age transition in southern Britain. Archaeological Journal, 176(1), 84-133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2018.1504859 Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

An Unusual Iron Age Enclosure at Fir Hill, Bossington & a Romano-British

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 64, 2009, 41-80 (Hampshire Studies 2009) AN UNUSUAL IRON AGE ENCLOSURE AT FIR HILL, BOSSINGTON AND A ROMANO-BRITISH CEMETERY NEAR BROOK, HAMPSHIRE: THE BROUGHTON TO TIMSBURY PIPELINE, PART 2 By LISA BROWN With MICHAEL J ALLEN, RACHEL EVERY, ROWENA GALE, STEPHANIE KNIGHT, JACQUELINE I MCKINLEY, LORRAINE MEPHAM and CHRIS J STEVENS, and illustrations by S E JAMES ABSTRACT sites investigated (Fig. 1, AJ), 5 produced no archaeological features (A, B, D, H and I). Fieldwork in advance of pipeline construction resultedThe earlier report focused on the late Saxon in the excavation of a transect through an unusual pottery production site at Michelmersh (Site triangular enclosure of earlymiddle Iron Age date J: ibid.). This paper concentrates on a transect (Site C) and the discovery of a previously unknown excavated across the presumed Iron Age settle- Romano-British cemetery (Site E). The enclosures ment enclosures at Fir Hill, Bossington (Site were previously recorded from aerial photographs C) and a previously unknown Romano-British and the investigation provided an opportunity to cemetery near Brook (Site E). Two less signifi- recover dating and environmental evidence as well cant sites - a Romano-British structure (Site F) as examine a small area of the interior. Other asso- and a medieval building (Site G) are reported ciated ditches and a smaller triple-ditched enclosure as summaries only. were also investigated. There is a hint that the large triangular enclosure had two phases of development, and although the surrounding ditch was 'defensive' FIR HILL, BOSSINGTON (SITE C) in scale it appears not to have been maintained or to have enclosed a substantial permanent settlement, The pipeline route crossed the enclosure the suggestion being that it may have functioned as complex at Fir Hill, south-east of Bossington, a a gathering place or stock enclosure. -

2018-2019 Annual Report and Financial Statements

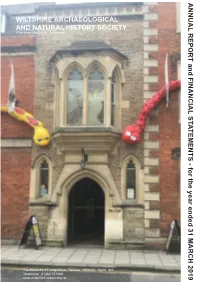

ANNUAL REPORT and FINANCIAL STATEMENTS - for the year ended 31 MARCH 2019 STATEMENTS REPORT and FINANCIAL ANNUAL WILTSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY (Company Limited by Guarantee) The Museum, 41 Long Street, Devizes, Wiltshire. SN10 1NS Telephone: 01380 727369 www.wiltshiremuseum.org.uk Our Audiences Our audiences are essential and work is ongoing, with funding through the Wessex Museums Partnership, to understand our audiences and develop projects and facilities to ensure they remain at the core of our activities. Our audience includes visitors, Society members, school groups, community groups, and researchers. Above is a testimonial given on one of the 2018/19 audience questionnaire forms. We attended the kids holiday craft workshop. These are BRILLIANT and we come every holiday. My son has Autism and can only attend holiday activities with me or my husband. This is the only facility e can enjoy as a family activity now he is 8 yrs old and we all really enjoy it. Below is a ‘word cloud’ comprising the three words used to describe the Museum on the forms. Cover: Made by Wiltshire Young Carers these decorated the front of the Museum during the Snakes exhibition in March and April 2019. (A company limited by guarantee) Charity Number 1080096 Company Registration Number 3885649 SUMMARY and OBJECTS The Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Researchers. Every year academic researchers Society (the Society) was founded in 1853. The carry out important research on items in the Society’s first permanent Museum opened in collection. There are over 500,000 items in Long Street in 1874. The Society is a registered the collections and details can be found in our charity and governed by Articles of Association.