S-12-6 Levy.Fm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTES on the BIRDS of CHIRIKOF ISLAND, ALASKA Jack J

NOTES ON THE BIRDS OF CHIRIKOF ISLAND, ALASKA JACK J. WITHROW, University of Alaska Museum, 907 Yukon Drive, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Isolated in the western Gulf of Alaska 61 km from nearest land and 74 km southwest of the Kodiak archipelago, Chirikof Island has never seen a focused investigation of its avifauna. Annotated status and abundance for 89 species recorded during eight visits 2008–2014 presented here include eastern range extensions for three Beringian subspecies of the Pacific Wren (Troglodytes pacificus semidiensis), Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia sanaka), and Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch (Leucost- icte tephrocotis griseonucha). A paucity of breeding bird species is thought to be a result of the long history of the presence of introduced cattle and introduced foxes (Vulpes lagopus), both of which persist to this day. Unique among sizable islands in southwestern Alaska, Chirikof Island (55° 50′ N 155° 37′ W) has escaped focused investigations of its avifauna, owing to its geographic isolation, lack of an all-weather anchorage, and absence of major seabird colonies. In contrast, nearly every other sizable island or group of islands in this region has been visited by biologists, and they or their data have added to the published literature on birds: the Aleutian Is- lands (Gibson and Byrd 2007), the Kodiak archipelago (Friedmann 1935), the Shumagin Islands (Bailey 1978), the Semidi Islands (Hatch and Hatch 1983a), the Sandman Reefs (Bailey and Faust 1980), and other, smaller islands off the Alaska Peninsula (Murie 1959, Bailey and Faust 1981, 1984). With the exception of most of the Kodiak archipelago these islands form part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge (AMNWR), and many of these publications are focused largely on seabirds. -

Terrestrial Ecology Enhancement

PROTECTING NESTING BIRDS BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR VEGETATION AND CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS Version 3.0 May 2017 1 CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3 2.0 BIRDS IN PORTLAND 4 3.0 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF PORTLAND BIRDS 4 3.1 Timing 4 3.2 Nesting Habitats 5 4.0 GENERAL GUIDELINES 9 4.1 What if Work Must Occur During Avoidance Periods? 10 4.2 Who Conducts a Nesting Bird Survey? 10 5.0 SPECIFIC GUIDELINES 10 5.1 Stream Enhancement Construction Projects 10 5.2 Invasive Species Management 10 - Blackberry - Clematis - Garlic Mustard - Hawthorne - Holly and Laurel - Ivy: Ground Ivy - Ivy: Tree Ivy - Knapweed, Tansy and Thistle - Knotweed - Purple Loosestrife - Reed Canarygrass - Yellow Flag Iris 5.3 Other Vegetation Management 14 - Live Tree Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Snag Removal - Shrub Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Grassland Mowing and Ground Cover Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Controlled Burn 5.4 Other Management Activities 16 - Removing Structures - Manipulating Water Levels 6.0 SENSITIVE AREAS 17 7.0 SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS 17 7.1 Species 17 7.2 Other Things to Keep in Mind 19 Best Management Practices: Avoiding Impacts on Nesting Birds Version 3.0 –May 2017 2 8.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND AN ACTIVE NEST ON A PROJECT SITE 19 DURING PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION? 9.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND A BABY BIRD OUT OF ITS NEST? 19 10.0 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR AVOIDING 20 IMPACTS ON NESTING BIRDS DURING CONSTRUCTION AND REVEGETATION PROJECTS APPENDICES A—Average Arrival Dates for Birds in the Portland Metro Area 21 B—Nesting Birds by Habitat in Portland 22 C—Bird Nesting Season and Work Windows 25 D—Nest Buffer Best Management Practices: 26 Protocol for Bird Nest Surveys, Buffers and Monitoring E—Vegetation and Other Management Recommendations 38 F—Special Status Bird Species Most Closely Associated with Special 45 Status Habitats G— If You Find a Baby Bird Out of its Nest on a Project Site 48 H—Additional Things You Can Do To Help Native Birds 49 FIGURES AND TABLES Figure 1. -

Percy Evans Freke

Percy Evans Freke Percy Evans-Freke was born in month 1774, at birth place, to John Evans-Freke (born Evans) and Lady Elizabeth Evans-Freke (born Evans) (born Gore). John was born in 1743, in Ireland. Lady was born in 1741, in Newton Gore, Mayo, Ireland. Percy had 5 siblings: John Evans-Freke, George Evans-Freke and 3 other siblings. Percy married Dorothea Evans-Freke (born Harvey). They had 9 children: Fenton John Evans-Freke, Jane Grace Bernard (born EVANS-FREKE) and 7 other children. Percy married Unknown. Percy Evans Freke. + . Read more. Full Wikipedia Article. Percy Evans Freke. Dublin. 50% (1/1). Timeline of ornithology. Rossitten Bird Observatory. Freke. 50% (1/1). + . Read more. John Anthony Evans-freke worked in PERCY SOUTHERN ESTATES LIMITED, HOTSPUR PRODUCTIONS LIMITED, PERCY NORTHERN ESTATES LIMITED, PERCY FARMING COMPANY LIMITED, LINHOPE FARMING COMPANY LIMITED as a Land agent. Active Directorships 0. HOTSPUR PRODUCTIONS LIMITED 02 March 1992 - 07 April 1992. PERCY FARMING COMPANY LIMITED 11 January 1992 - 07 April 1992. PERCY NORTHERN ESTATES LIMITED 11 January 1992 - 07 April 1992. Evans-Freke of Castle Freke in the Baronetage of Ireland (1768, after 1807). 1st Baron Carbery. George Evans, 1st Baron Carbery (1680â“1749) married Anne Stafford (d.1757) sister and coheiress of William Stafford of Laxton. George Patrick Percy Evans-Freke, 7th Baron Carbery (1810â“1889). William Charles Evans-Freke, 8th Baron Carbery (1812â“1894). Algernon William George Evans-Freke, 9th Baron Carbery (1868â“1898). John Evans-Freke later Carbery, 10th Baron Carbery (1892â“1970). Percy Augustus Evans-Freke was the son of Percy Evans-Freke and Dorothea Harvey.2 He died on 15 January 1847, unmarried.1 He gained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.1 In 1845 he was granted the rank of a baron's younger son.1. -

CCBC Whooosletter February 2017

CARROLL COUNTY BIRD CLUB Volume 4, Number 4 Winter 2017 The Whooosletter At Last Issue A Quarterly Publication of the Carroll County Bird Club At last! The Young Artists are baaacckkk! Another issue of The Whooosletter. I wish I could Carroll County Bird Club will be sponsoring this tell you why it took so long. It would be easy to use endeavor for 2017 to help youth in Carroll Coun- the “busy at work” excuse, but most of our ty connect with birds and nature through art. The members still work for a living. And many of them exhibit will run from April 22nd until May 19th at lead exciting lives in spite of it. Bear Branch Nature Center. The opening reception, awards, and silent auction to benefit Bear Branch will Case in point would be Craig Storti. His continuing be held on April 22nd at 5:30 P.M. Please come out search for the Snail Kite while on vacation in and enjoy this event. Florida has appeared in the last two issues. Will he finally bag this rarity? Read his article on page 2 to This year is particularly exciting as the MOS has find out. awarded us a grant to support the youth art exhibit. Bowman’s Home and Gardens is happy to provide Dave and Maureen Harvey were probably our most items such as bird feeders as prizes, and the libraries well-travelled birders even before they retired. That and schools are enthusiastic about partnering with us hasn’t changed. They recently went to Cuba. Dave again. -

Libro ING CAC1-36:Maquetación 1.Qxd

© Enrique Montesinos, 2013 © Sobre la presente edición: Organización Deportiva Centroamericana y del Caribe (Odecabe) Edición y diseño general: Enrique Montesinos Diseño de cubierta: Jorge Reyes Reyes Composición y diseño computadorizado: Gerardo Daumont y Yoel A. Tejeda Pérez Textos en inglés: Servicios Especializados de Traducción e Interpretación del Deporte (Setidep), INDER, Cuba Fotos: Reproducidas de las fuentes bibliográficas, Periódico Granma, Fernando Neris. Los elementos que componen este volumen pueden ser reproducidos de forma parcial siem- pre que se haga mención de su fuente de origen. Se agradece cualquier contribución encaminada a completar los datos aquí recogidos, o a la rectificación de alguno de ellos. Diríjala al correo [email protected] ÍNDICE / INDEX PRESENTACIÓN/ 1978: Medellín, Colombia / 77 FEATURING/ VII 1982: La Habana, Cuba / 83 1986: Santiago de los Caballeros, A MANERA DE PRÓLOGO / República Dominicana / 89 AS A PROLOGUE / IX 1990: Ciudad México, México / 95 1993: Ponce, Puerto Rico / 101 INTRODUCCIÓN / 1998: Maracaibo, Venezuela / 107 INTRODUCTION / XI 2002: San Salvador, El Salvador / 113 2006: Cartagena de Indias, I PARTE: ANTECEDENTES Colombia / 119 Y DESARROLLO / 2010: Mayagüez, Puerto Rico / 125 I PART: BACKGROUNG AND DEVELOPMENT / 1 II PARTE: LOS GANADORES DE MEDALLAS / Pasos iniciales / Initial steps / 1 II PART: THE MEDALS WINNERS 1926: La primera cita / / 131 1926: The first rendezvous / 5 1930: La Habana, Cuba / 11 Por deportes y pruebas / 132 1935: San Salvador, Atletismo / Athletics -

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's Advocacy for Gender

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s Advocacy for Gender Equality in Ornithology TANJA HAMMEL Department of History, University of Basel This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist’s life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber’s knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds’ collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage -

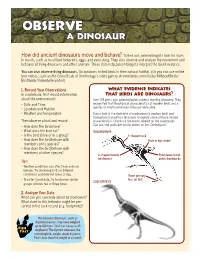

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

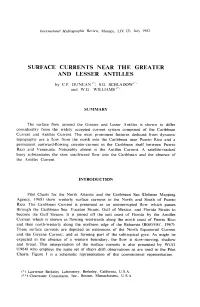

Surface Currents Near the Greater and Lesser Antilles

SURFACE CURRENTS NEAR THE GREATER AND LESSER ANTILLES by C.P. DUNCAN rl, S.G. SCHLADOW1'1 and W.G. WILLIAMS SUMMARY The surface flow around the Greater and Lesser Antilles is shown to differ considerably from the widely accepted current system composed of the Caribbean Current and Antilles Current. The most prominent features deduced from dynamic topography are a flow from the north into the Caribbean near Puerto Rico and a permanent eastward-flowing counter-current in the Caribbean itself between Puerto Rico and Venezuela. Noticeably absent is the Antilles Current. A satellite-tracked buoy substantiates the slow southward flow into the Caribbean and the absence of the Antilles Current. INTRODUCTION Pilot Charts for the North Atlantic and the Caribbean Sea (Defense Mapping Agency, 1968) show westerly surface currents to the North and South of Puerto Rico. The Caribbean Current is presented as an uninterrupted flow which passes through the Caribbean Sea, Yucatan Straits, Gulf of Mexico, and Florida Straits to become the Gulf Stream. It is joined off the east coast of Florida by the Antilles Current which is shown as flowing westwards along the north coast of Puerto Rico and then north-westerly along the northern edge of the Bahamas (BOISVERT, 1967). These surface currents are depicted as extensions of the North Equatorial Current and the Guyana Current, and as forming part of the subtropical gyre. As might be expected in the absence of a western boundary, the flow is slow-moving, shallow and broad. This interpretation of the surface currents is also presented by WUST (1964) who employs the same set of ship’s drift observations as are used in the Pilot Charts. -

Historical Review of Systematic Biology and Nomenclature - Alessandro Minelli

BIOLOGICAL SCIENCE FUNDAMENTALS AND SYSTEMATICS – Vol. II - Historical Review of Systematic Biology and Nomenclature - Alessandro Minelli HISTORICAL REVIEW OF SYSTEMATIC BIOLOGY AND NOMENCLATURE Alessandro Minelli Department of Biology, Via U. Bassi 58B, I-35131, Padova,Italy Keywords: Aristotle, Belon, Cesalpino, Ray, Linnaeus, Owen, Lamarck, Darwin, von Baer, Haeckel, Sokal, Sneath, Hennig, Mayr, Simpson, species, taxa, phylogeny, phenetic school, phylogenetic school, cladistics, evolutionary school, nomenclature, natural history museums. Contents 1. The Origins 2. From Classical Antiquity to the Renaissance Encyclopedias 3. From the First Monographers to Linnaeus 4. Concepts and Definitions: Species, Homology, Analogy 5. The Impact of Evolutionary Theory 6. The Last Few Decades 7. Nomenclature 8. Natural History Collections Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary The oldest roots of biological systematics are found in folk taxonomies, which are nearly universally developed by humankind to cope with the diversity of the living world. The logical background to the first modern attempts to rationalize the classifications was provided by Aristotle's logic, as embodied in Cesalpino's 16th century classification of plants. Major advances were provided in the following century by Ray, who paved the way for the work of Linnaeus, the author of standard treatises still regarded as the starting point of modern classification and nomenclature. Important conceptual progress was due to the French comparative anatomists of the early 19th century UNESCO(Cuvier, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire) – andEOLSS to the first work in comparative embryology of von Baer. Biological systematics, however, was still searching for a unifying principle that could provide the foundation for a natural, rather than conventional, classification.SAMPLE This principle wasCHAPTERS provided by evolutionary theory: its effects on classification are already present in Lamarck, but their full deployment only happened in the 20th century. -

Beginning Birdwatching 2021 Resource List

Beginning Birdwatching 2021 Resource List Field Guides and how-to Birds of Illinois-Sheryl Devore and Steve Bailey The New Birder’s Guide to Birds of North America-Bill Thompson III Sibley’s Birding Basics-David Sibley Peterson Guide to Bird Identification-in 12 Steps-Howell and Sullivan Clubs and Organizations Chicago Ornithological Society-www.chicagobirder.org DuPage Birding Club-www.dupagebirding.org Evanston-North Shore Bird Club-www.ensbc.org Illinois Audubon Society-www.illinoisaudubon.org Will, Kane, Lake Cook county Audubon chapters (and others in Illinois) Illinois Ornithological Society-www.illinoisbirds.org Illinois Young Birders-(ages 9-18) monthly field trips and yearly symposiums Wild Things Conference 2021 American Birding Association- aba.org On-line Resources Cornell Lab of Ornithology All About Birds, eBird, Birdcast Radar, Macaulay Library (sounds), Youtube series: Inside Birding: Shape, Habitat, Behavior DuPage Birding Club-Youtube channel, Mini-tutorials, Bird-O-Bingo card, DuPage hot spot descriptions Facebook: Illinois Birding Network, Illinois Rare Bird Alert, World Girl Birders, Raptor ID, What’s this Bird? Birdnote-can subscribe for informative, weekly emails-also Podcast Birdwatcher’s Digest podcasts: Out There With the Birds, Birdsense Podcasts: Laura Erickson’s For the Birds, Ray Brown’s Talkin’ Birds, American Birding Podcast (ABA) Blog: Jeff Reiter’s “Words on Birds” (meet Jeff on his monthly walks at Cantigny, see DuPage Birding Club website for schedule) Illinois Birding by County-countywiki.ilbirds.com -

Paleogeography of the Caribbean Region: Implications for Cenozoic Biogeography

PALEOGEOGRAPHY OF THE CARIBBEAN REGION: IMPLICATIONS FOR CENOZOIC BIOGEOGRAPHY MANUEL A. ITURRALDE-VINENT Research Associate, Department of Mammalogy American Museum of Natural History Curator, Geology and Paleontology Group Museo Nacional de Historia Natural Obispo #61, Plaza de Armas, CH-10100, Cuba R.D.E. MA~PHEE Chairman and Curator, Department of Mammalogy American Museum of Natural History BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Number 238, 95 pages, 22 figures, 2 appendices Issued April 28, 1999 Price: $10.60 a copy Copyright O American Museum of Natural History 1999 ISSN 0003-0090 CONTENTS Abstract ....................................................................... 3 Resumen ....................................................................... 4 Resumo ........................................................................ 5 Introduction .................................................................... 6 Acknowledgments ............................................................ 8 Abbreviations ................................................................ 9 Statement of Problem and Methods ............................................... 9 Paleogeography of the Caribbean Region: Evidence and Analysis .................. 18 Early Middle Jurassic to Late Eocene Paleogeography .......................... 18 Latest Eocene to Middle Miocene Paleogeography .............................. 27 Eocene-Oligocene Transition (35±33 Ma) .................................... 27 Late Oligocene (27±25 Ma) ...............................................