Theatre Theory and Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Performativity of Performance Documentation

THE PERFORMATIVITY OF PERFORMANCE DOCUMENTATION Philip Auslander onsider two familiar images from the history of performance and body art: one from the documentation of Chris Burden’s Shoot (1971), the notori- ous piece for which the artist had a friend shoot him in a gallery, and Yves CKlein’s famous Leap into the Void (1960), which shows the artist jumping out of a second-story window into the street below. It is generally accepted that the first image is a piece of performance documentation, but what is the second? Burden really was shot in the arm during Shoot, but Klein did not really jump unprotected out the window, the ostensible performance documented in his equally iconic image. What difference does it make to our understanding of these images in relation to the concept of performance documentation that one documents a performance that “really” happened while the other does not? I shall return to this question below. As a point of departure for my analysis here, I propose that performance docu- mentation has been understood to encompass two categories, which I shall call the documentary and the theatrical. The documentary category represents the traditional way in which the relationship between performance art and its documentation is conceived. It is assumed that the documentation of the performance event provides both a record of it through which it can be reconstructed (though, as Kathy O’Dell points out, the reconstruction is bound to be fragmentary and incomplete1) and evidence that it actually occurred. The connection between performance and docu- ment is thus thought to be ontological, with the event preceding and authorizing its documentation. -

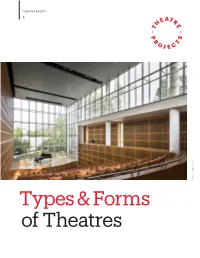

Types & Forms of Theatres

THEATRE PROJECTS 1 Credit: Scott Frances Scott Credit: Types & Forms of Theatres THEATRE PROJECTS 2 Contents Types and forms of theatres 3 Spaces for drama 4 Small drama theatres 4 Arena 4 Thrust 5 Endstage 5 Flexible theatres 6 Environmental theatre 6 Promenade theatre 6 Black box theatre 7 Studio theatre 7 Courtyard theatre 8 Large drama theatres 9 Proscenium theatre 9 Thrust and open stage 10 Spaces for acoustic music (unamplified) 11 Recital hall 11 Concert halls 12 Shoebox concert hall 12 Vineyard concert hall, surround hall 13 Spaces for opera and dance 14 Opera house 14 Dance theatre 15 Spaces for multiple uses 16 Multipurpose theatre 16 Multiform theatre 17 Spaces for entertainment 18 Multi-use commercial theatre 18 Showroom 19 Spaces for media interaction 20 Spaces for meeting and worship 21 Conference center 21 House of worship 21 Spaces for teaching 22 Single-purpose spaces 22 Instructional spaces 22 Stage technology 22 THEATRE PROJECTS 3 Credit: Anton Grassl on behalf of Wilson Architects At the very core of human nature is an instinct to musicals, ballet, modern dance, spoken word, circus, gather together with one another and share our or any activity where an artist communicates with an experiences and perspectives—to tell and hear stories. audience. How could any one kind of building work for And ever since the first humans huddled around a all these different types of performance? fire to share these stories, there has been theatre. As people evolved, so did the stories they told and There is no ideal theatre size. The scale of a theatre the settings where they told them. -

COURSE OUTLINE ETT205 Arts and Entertainment Management 3 3 15

Mercer County Community College COURSE OUTLINE ETT205 Arts and Entertainment Management 3 Course Number Course Title Credits 3 15 week Class or Laboratory Clinical or Studio Practicum, Course Length Lecture Work Hours Hours Co-op, Internship (15 week, Hours 10 week, etc.) None None_ Performance on an Examination/Demonstration Alternate Delivery Methods (Placement Score (if applicable); minimum CLEP score) (Online, Telecourse [give title of videos]) Required Materials: Sports and Entertainment Management, Kenneth Kaser & John R. Brooks, Jr. South-Western Thomson Publishing, 2005. ISBN: 0538438290 Managing a Nonprofit Organization in the Twenty-First Century, Third Revised Edition and Up, Thomas Wolf and Barbara Carter. Free Press, 1999. ISBN: 0684849909 Catalog Description: An introduction to common issues and best practices in the management of arts and entertainment organizations. Students will gain a basic understanding of business requirements and challenges in producing entertainment. Topics include common management structures in not-for-profit and for-profit arts and entertainment companies, marketing, public relations, fundraising, budgeting, and human resources. Legal concerns such as contracts, copyright, licensing, and royalties will also be discussed. Prerequisites: Corequisites: ETT101 or permission of the Coordinator None Last Revised: February 2017 Course Coordinator (name, email, phone extension): Scott Hornick, Assistant Professor of Music. (609) 570-3716; [email protected] Available Resources: - 1 - ETT205- Arts and Entertainment Management Directory of Theatre Training Programs: Profiles of College and Conservatory Programs throughout the United States. Dorset Theatre Festival and Colony House. Field, Shelly. (1992). Career Opportunities in Theater and the Performing Arts. Facts on File Publishing. Gassner, John. (1953). Producing the Play. Dryden Press. -

Humanities Approved Distribution Course List (P/S)

HUMANITIES APPROVED DISTRIBUTION COURSE LIST (P/S) = Performance/Skills courses use of a mix of lecture, guided activities, and individual projects as teaching and learning methods. These courses often include creative projects and performances. Typical performance/skills courses include: studio art, music ensembles and creative writing courses. + Courses no longer offered at TCC. All courses listed below are 5 credit classes Course # Course Name ANTH& 207 Linguistic Anthropology ART& 100 Art Appreciation ART 102 Two-Dimensional Design (P/S) ART 103 Three-Dimensional Design (P/S) ART 105 Beginning Drawing (P/S) ART 106 Drawing (P/S) ART 110 Beginning Graphic Design (P/S) ART 111 Intermediate Graphic Design (P/S) ART 131 Beginning Ceramics (P/S) ART 132 Intermediate Ceramics I ART 133 Intermediate Ceramics II ART 146 Beginning Photography (P/S) ART 147 Introduction to Digital Photography (P/S) ART 150 Beginning Printmaking (P/S) ART 156 Beginning Painting (P/S) ART 172 Beginning Sculpture (P/S) ART 180 Art for Elementary Teachers ART 199 Gallery Viewing Lab ART 201 History of Western Art: Ancient ART 202 History of Western Art: Medieval and Renaissance ART 203 History of Western Art: Baroque through Modern ART 231 Low-Fire Ceramics ART 232 Surface Embellishment and Form Alteration ART 247 Intermediate Digital Photography CMST& 101 Introduction to Communications CMST 110 Multicultural Communications CMST& 220 Public Speaking ENGL& 220 Introduction to Shakespeare ENGL 234 Introduction to Mythology and Folk Stories ENGL 242 Contemporary Non-Western -

Drama/Theatre/Performance

DRAMA/THEATRE/PERFORMANCE What is implied when we refer to the study of performing arts as ‘drama’, ‘theatre’ or ‘performance’? Each term identifies a different tradition of thought and offers different possibilities to the student or practitioner. This book examines the history and use of the terms and investigates the different philosophies, politics, languages and institutions with which they are associated. Simon Shepherd and Mick Wallis: • analyse attitudes to drama, theatre and performance at different historical junctures • trace a range of political interventions into the field(s) • explore and contextualise the institutionalisation of drama and theatre as university subjects, then the emergence of ‘performance’ as practice, theory and academic discipline • guide readers through major approaches to drama, theatre and performance, from theatre history and sociology, through theories of ritual and play, to the idea of performance as paradigm for a post- modern age • discuss crucial terms such as action, alienation, catharsis, character, empathy, interculturalism, mimesis, presence and representation in a substantial ‘keywords’ section. Continually linking their analysis to wider cultural concerns, the authors here offer the most wide-ranging and authoritative guide available to a vibrant, fast-moving field and vigorous debates about its nature, purpose and place in the academy. Simon Shepherd is Director of Programmes at Central School of Speech and Drama in London. Mick Wallis is Professor of Performance and Culture at the University of Leeds. THE NEW CRITICAL IDIOM Series Editor: John Drakakis, University of Stirling The New Critical Idiom is an invaluable series of introductory guides to today’s critical terminology. Each book: . provides a handy, explanatory guide to the use (and abuse) of the term . -

The Performance Role of Reader's Theatre in a Literature Classroom

The CEA Forum Summer/Fall 2006: 35.2 ___________________________________________ _______________________ THE PERFORMANCE ROLE OF READER'S THEATRE IN A LITERATURE CLASSROOM Gerald Lee Ratliff _______________________ The traditional classroom role of oral interpretation of literature appears to view performance from rhetorical perspectives that reflect classical tenets of oral persuasion, public speaking and recitative reading. Although acknowledging the values of appreciation, recognition, and understanding a literary text's inherent "dramatic" qualities, there is less agreement on the classroom performance skills needed to give life and meaning to the feelings and thoughts of a literary character. For some, oral interpretation of literature in a classroom setting remains an informal act of vocal "re-creation," the performer's voice merely a convenient instrument to read aloud the author's printed words to an audience of listeners. Others view oral interpretation of literature as a formal classroom "performance" that shares a decidedly theatrical impulse with conventional acting theories like role-playing or character-building, and that emphasizes physical as well as vocal techniques to give more dimension to the interpretation of a literary character. Today, however, the basic principles of Reader's Theatre have begun to translate the classroom oral interpretation of literature from obscure words on a printed page into an exciting performance laboratory. Whether constructed on the solid foundation of more traditional theories or inspired by experimental discoveries, today's Reader's Theatre cultivates the most imaginative instructional techniques available for students to see, hear, and feel literature in classroom performance. Although there is no prescribed formula needed to give vocal and physical shape or substance to a literary text, the theatrical impulse in Reader's Theatre is interested in pursuing the artistic and dramatic visualization of the actions, attitudes and emotions of literary characters in classroom performance. -

Theatre (THE) 1

Theatre (THE) 1 THE 188. The Contemporary English Theatre. (1 h) THEATRE (THE) Explores the English theatre through theatre attendance in London and other English theatre centers. Readings, lectures. Participants submit THE 100. Participation. (0.5 h) reviews of the plays and complete a journal of informal reactions to the Attendance/participation in Mainstage and Studio performances and plays, the sites and the variety of cultural differences observed. Two other events as established by the department. Specific attendance/ weeks. Offered in London before spring term. Pass/fail only. P-POI. participation requirements will be established at the beginning of each THE 230. Advanced Dynamics. (3 h) semester. Assignments for technical production are made through Focus on opening and strengthening the actor's instrument by building consultation with the technical and design faculty. May be repeated for on work done in THE 145. P-THE 145. credit. P-POI. THE 240. Class Act. (3 h) THE 110. Introduction to Western Theatre. (3 h) Interdisciplinary theatre class that moves dramatic literature from Survey of the theory and practice of the major disciplines of Western page to stage as students prepare and present scenes used in courses theatre art: acting, directing, playwriting, and design. Optional lab- throughout the University. P-THE 140 or POI. (D) THE 110L. (D) THE 241. Acting for the Camera. (3 h) THE 110L. Intro to Theatre-Lab. (1 h) Introduces the theory and practice of acting for the camera. Focused on Participation in production team on Mainstage as assigned. P or C- film/video/TV acting, may also include commercials and other formats. -

Renowned Artist Gary Morris Inks Joint Booking Deal with High Performance Entertainment and Alkahest Artists & Attractions

Contact: Cindy Dupree Phone: (615) 327-0100 Email: [email protected] RENOWNED ARTIST GARY MORRIS INKS JOINT BOOKING DEAL WITH HIGH PERFORMANCE ENTERTAINMENT AND ALKAHEST ARTISTS & ATTRACTIONS Gary Morris, renowned sinGer, sonGwriter and Broadway actor, has signed a joint booking deal with High Performance Entertainment and AlKahest Artists & Attractions. David Kiswiney’s Nashville- based High Performance Entertainment agency will handle fairs, festivals, casinos and corporate bookings for Morris, while AlKahest Artists & Attractions, under the direction of President Elizabeth Bridges, will oversee theatres, performinG arts centers and international bookings. “There is a depth to Gary’s performance that speaks to today’s audiences,” BridGes said. “Always true to his music, loyal to his friends and fans, his command of an audience by way of talent and charm – and that amazing voice - maKes for a special concert experience. We are honored to be worKinG with Gary.” “AddinG the tremendously talented Gary Morris to the roster of High Performance Entertainment is a foundational buildinG blocK for our new company,” said David Kiswiney, president. “We’re thrilled he’s on board.” “I’m launchinG this next chapter of my career with two seasoned professionals I can trust. I have the best of both worlds with David and Elizabeth,” Morris said. “As a result of our collaboration, and Pam Lewis making it happen, I’m going to get to continue to share my heart and my music with audiences around the country and the world.” Morris is best Known for his Golden voice, featured on such hits as “Wind Beneath My WinGs,” and “Why Lady Why,” and for his epic role of Jean Valjean in Broadway’s “Les Misérables.” His recent album, “Sense of Pride,” released in the fall of 2018, is described by Morris as “the most personal musical work I’ve attempted about my life and how I see the world.” HiGh Performance Entertainment, launched in 2018 by veteran aGent David Kiswiney, also represents Exile, Gunnar and the Grizzly Boys, Gil Grand, DereK St. -

An Analysis of Satire Megan Leboeuf University of Rhode Island, [email protected]

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2007 The oP wer of Ridicule: An Analysis of Satire Megan LeBoeuf University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation LeBoeuf, Megan, "The oP wer of Ridicule: An Analysis of Satire" (2007). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 63. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/63http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/63 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power of Ridicule An Analysis of Satire Megan LeBoeuf Faculty Sponsor: Walter von Reinhart April 27, 2007 LeBoeuf 1 Why Satire? Satire is a powerful art form which has the ability to point out the deficiencies in certain human behaviors and the social issues which result from them in such a way that they become absurd, even hilarious, which is therefore entertaining and reaches a wide audience. Satire also has the ability to protect its creator from culpability for criticism, because it is implied rather than overtly stated; in this way, it becomes a powerful tool for dissenters in difficult or oppressive political and social periods. According to Canadian television and newspaper critic John Doyle, "there are specific periods when satire is necessary. We've entered one of those times" (Globe and Mail). -

Performance Art and Drawing

Performance art and drawing Clifford Owens Performance art is an image. good drawing (usually representational or anatomically accurate) looks like a good drawing, a display of academic artesian dexterity. Certainly, this pre- A sumption about the value and virtue of drawing is a misnomer; there are, in fact, as many forms and formalisms of drawing as there are practices of drawing. On the one hand, some drawings rely on deft hand-eye coordination; on the other hand, more abstract formalisms of drawing rely on an acute awareness of the body and emotional gestalt. Studio Visit: Drawings with Joan Jonas Above: Studio Visit: Joan Jonas (2005). Archival pigment print, ed. 1/5, 2AP. 24" x 30". Below: Studio Visit: Drawings with Joan Jonas (2005). Installation view. Six charcoal and graphite drawings on paper. Studio Visit: Drawings with Joan Jonas is the outcome of a project that considered, as Courtesy the artist. its conceptual point of departure, the function of a studio visit. Borrowing from Daniel Buren’s insightful essay “The Function of the Studio,” in which, in part, he consid- ers the space (the studio) in which a work of art is created and the space in which a work of art is exhibited and received by a viewer (the museum), I was interested in the function of the studio visit. Namely, its peculiar social dynamic between an artist and a viewer within the privatized space of creation that is, in large measure, predicated on a particular social contract informed by a certain professional, inter- personal decorum. In this 2005 project, “ Studio Visits,” I invited intergenerational artists and a historian and curator of performance art to engage with me in an active studio visit, which is contrary to the professional decorum of passive, “disinterested contemplation” during a studio visit. -

The Performance of Literate Practices: Rhetoric, Writing, and Stand-Up Comedy

The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning Volume 22 Winter 2016-2017 Article 9 1-1-2017 The Performance of Literate Practices: Rhetoric, Writing, and Stand-up Comedy J. Michael Rifenburg University of North Georgia Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl Recommended Citation Rifenburg, J. Michael (2017) "The Performance of Literate Practices: Rhetoric, Writing, and Stand-up Comedy," The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning: Vol. 22 , Article 9. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl/vol22/iss1/9 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl. JAEPL, Vol. 22, Winter 2016–2017 The Performance of Literate Practices: Rhetoric, Writing, and Stand-up Comedy J. Michael Rifenburg omedian John Crist and I are standing in the middle of the student center at Cthe University of North Georgia’s Gainesville campus. It’s noon on a Tuesday in mid-April. Two weeks are left in the semester, and the campus activity board brought in John, a comedian for the past five years, for stress relief. Next week is ice cream and pet therapy. All around, students, faculty, and staff sit at circle tables, eating, texting, talking, and gaming. Most are electronically plugged into something. The steady din of the ice machine, the cash register, and conversation fill the space. -

Georgia Performance Standards Fine Arts

Georgia Performance Standards Fine Arts GRADE: 4 THEATRE ARTS 4 TAES4.1 Analyzing and constructing meaning from theatrical experiences, dramatic literature, and electronic media a. Defines, and uses theatre vocabulary b. Explains how theatrical experiences reflect life c. Analyzes dramatic elements such as plot, point of view, conflict, resolution, and/or significant events d. Summarizes theatrical experiences, dramatic literature, and electronic media experiences e. Makes inferences about setting, character, events and main ideas in theatre experiences TAES4.2 Developing scripts through improvisation and other theatrical methods a. Uses the playwriting process: pre-write/pre-play; prepare to write/plan dramatization; write/ dramatize; reflect and edit; re-write/play; publish/perform b. Analyzes the elements of a well-written script c. Researches and incorporates a variety of media into a script d. Creates in-depth scripts that include character motivation and dialogue e. Creates an organizing structure for writing scripts TAES4.3 Acting by developing, communicating, and sustaining roles within a variety of situations and environments a. Uses articulation, volume and vocal variety to communicate thoughts, emotions and actions of a character b. Uses stage areas and body movement to communicate thoughts, emotions, and actions of a character c. Uses imagination and real life experience to portray characters d. Collaborates with an ensemble to create theatre e. Dramatizes literature and original scripts through various dramatic forms such as story drama, pantomime, process drama, puppetry, improvisation and readers’ theatre TAES4.4 Designing and executing artistic and technical elements of theatre a. Uses technical theatre elements to design simple costumes, props, sets, sound and lighting b.