Rayuwa MIDTERM QUALITATIVE EVALUATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

SFG1950 Public Disclosure Authorized _________ Projet d’Appui à l’Agriculture Sensible aux Risques Climatiques (PASEC) _________ Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized CADRE DE GESTION ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL (CGES) Public Disclosure Authorized RAPPORT DEFINITIF Janvier 2016 TABLE DES MATIERES ESMF SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 7 RESUME ............................................................................................................................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 11 CONTEXTE ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 OBJECTIFS DE L’ÉTUDE ..................................................................................................................................... 11 MÉTHODOLOGIE ................................................................................................................................................ 12 STRUCTURATION DU RAPPORT .......................................................................................................................... 12 1. DESCRIPTION DU PROJET ................................................................................................................. -

Arrêt N° 01/10/CCT/ME Du 23 Novembre 2010

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du vingt trois novembre deux mil dix tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-031 du 27 mai 2010 portant code électoral et ses textes modificatifs subséquents ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2010-668/PCSRD du 1er octobre 2010 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le référendum sur la Constitution de la VIIème République ; Vu la requête en date du 8 novembre 2010 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI) et les pièces jointes ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 003/PCCT du 8 novembre 2010 de Madame le Président du Conseil Constitutionnel portant désignation d’un Conseiller-Rapporteur ; Ensemble les pièces jointes ; Après audition du Conseiller – rapporteur et en avoir délibéré conformément à la loi ; EN LA FORME Considérant que par lettre n° 190/P/CENI en date du 8 novembre 2010, le Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI) a saisi le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition aux fins de valider -

Draft Outline

Annual Report Year 1 – 23/12/2016 to 22/12/2017 Submission Date: 20 March 2018 Agreement Number: AID-625-A-17-00001 Activity Start Date and End Date: 12/23/2016 to 01/22/2021 AOR Name: Jennifer Karsner Submitted by: Alissa Karg Girard, Chief of Party Lutheran World Relief Boulevard Mali Béro, Avenue du Kawar, Niamey, Niger Tel: +227.96.26.73.26 Email: [email protected] The content of this report is the responsibility of Lutheran World Relief and does not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. LIST OF ACRONYMS AOR Agreement Officer Representative AE Auxiliaires de l’Elevage CBO Community-Based Organization CEB Contribution à l’Education de Base EMMP Environmental Monitoring and Mitigation Plan F&A Finance and Administration FTF Feed the Future FMNR Farmer-Managed Natural Regeneration FY Fiscal Year GCC Global Climate Change GDA Global Development Alliance GPS Global Positioning System ICT Information and Communications Technologies INRAN Institut National de Recherches Agricoles du Niger IR Intermediate Result LWR Lutheran World Relief MACF Margaret A. Cargill Foundation MCC Millennium Challenge Corporation MEL Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (Plan) MOU Memorandum of Understanding ONAHA Office National des Aménagements Hydro-Agricoles OPVN Office des Produits Vivriers du Niger PEA Producer Enterprise Agent PIRS Project Indicator Reference Sheet RISE Resilience in the Sahel Enhanced SAREL Sahel Resilience Learning Project SVPP Service Vétérinaire Privé de Proximité TOT Training of Trainers USAID United States -

Reinforcing Agro Dealer Networks in Niger - an Impact Evaluation Study

REINFORCING AGRO DEALER NETWORKS IN NIGER - AN IMPACT EVALUATION STUDY Final Report Submitted to the 3ie by Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research University of Ghana June, 2017 Reinforcing Agro Dealer Networks in Niger: An Impact Evaluation Study By Robert Darko Osei*, ISSER, University of Ghana, Legon Accra Isaac Osei-Akoto, ISSER, University of Ghana, Legon Accra Felix Ankoma Asante ISSER, University of Ghana, Legon Accra Mamadou Adam, INRAN, Niamey, Niger Ama Fenny, ISSER, University of Ghana, Legon Accra Pokuaa Adu, ISSER, University of Ghana, Legon Accra Louis Hodey, ISSER, University of Ghana, Legon Accra Acknowledgement We wish to acknowledge 3ie for funding and technical review and support throughout this study. We also wish to thank AGRA monitoring and evaluation office for the continued support and readiness to answer questions whenever we approached them. We will also wish to thank the implementing partners CEB who have been very tolerant throughout the study period. Finally we wish to thank various participants for their invaluable comments during our stakeholder meetings and other engagements. All views expressed in this study are those of the authors only. Email of corresponding Author: [email protected] Table of Content TABLE OF CONTENT ...................................................................................................................................... I LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

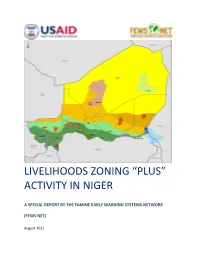

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès Public Disclosure Authorized ======================================== CABINET DU PREMIER MINISTRE ====================================================== Projet de Gestion des Risques de Catastrophes et de Développement Urbain Public Disclosure Authorized CADRE DE GESTION ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL (CGES) Public Disclosure Authorized RAPPORT ACTUALISE Version Définitive Février 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized TABLE DES MATIERES TABLE DES MATIERES .................................................................................................................................................I LISTE DES CARTES .................................................................................................................................................... III LISTE DES TABLEAUX ............................................................................................................................................... IV ACRONYMES ................................................................................................................................................................ VI INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................ 9 I. DESCRIPTION DU PROJET ................................................................................................................... 11 1.1. OBJECTIFS DE DEVELOPPEMENT .................................................................................................................... -

Stratégie De Développement Rural

République du Niger Comité Interministériel de Pilotage de la Stratégie de Développement Rural Secrétariat Exécutif de la SDR Stratégie de Développement Rural ETUDE POUR LA MISE EN PLACE D’UN DISPOSITIF INTEGRE D’APPUI CONSEIL POUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL AU NIGER VOLET DIAGNOSTIC DU RÔLE DES ORGANISATIONS PAYSANNES (OP) DANS LE DISPOSITIF ACTUEL D’APPUI CONSEIL Rapport provisoire Juillet 2008 Bureau Nigérien d’Etudes et de Conseil (BUNEC - S.A.R.L.) SOCIÉTÉ À RESPONSABILITÉ LIMITÉE AU CAPITAL DE 10.600.000 FCFA 970, Boulevard Mali Béro-km-2 - BP 13.249 Niamey – NIGER Tél : +227733821 Email : [email protected] Site Internet : www.bunec.com 1 AVERTISSEMENTS A moins que le contexte ne requière une interprétation différente, les termes ci-dessous utilisés dans le rapport ont les significations suivantes : Organisation Rurale (OR) : Toutes les structures organisées en milieu rural si elles sont constituées essentiellement des populations rurales Organisation Paysanne ou Organisation des Producteurs (OP) : Toutes les organisations rurales à caractère associatif jouissant de la personnalité morale (coopératives, groupements, associations ainsi que leurs structures de représentation). Organisation ou structure faîtière: Tout regroupement des OP notamment les Union Fédération, Confédération, associations, réseaux et cadre de concertation. Union : Regroupement d’au moins 2 OP de base, c’est le 1er niveau de structuration des OP. Fédération : C’est un 2ème niveau de structuration des OP qui regroupe très souvent les Unions. Confédération : Regroupement les fédérations des Unions, c’est le 3ème niveau de structuration des OP Membre des OP : Personnes physiques ou morales adhérents à une OP Adhérents : Personnes physiques membres des OP Promoteurs ou structures d’appui ou partenaires : ce sont les services de l’Etat, ONG, Projet ou autres institutions qui apportent des appuis conseil, technique ou financier aux OP. -

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique Au Niger»

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique au Niger» DIFEB, le 16 Août 2019 SOMMAIRE CEV Plan de déploiement Détails Zone 1 Détails Zone 2 Avantages/Limites CEV Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote CEV: Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote Notion apparue avec l’introduction de la Biométrie dans le système électoral nigérien. ▪ Avec l’utilisation de matériels sensible (fragile et lourd), difficile de faire de maison en maison pour un recensement, C’est l’emplacement physique où se rendront les populations pour leur inscription sur la Liste Electorale Biométrique (LEB) dans une localité donnée. Pour ne pas désorienter les gens, le CEV servira aussi de lieu de vote pour les élections à venir. Ainsi, le CEV contiendra un ou plusieurs bureaux de vote selon le nombre de personnes enrôlées dans le centre et conformément aux dispositions de création de bureaux de vote (Art 79 code électoral) COLLECTE DES INFORMATIONS SUR LES CEV Création d’une fiche d’identification de CEV; Formation des acteurs locaux (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil) pour le remplissage de la fiche; Remplissage des fiches dans les communes (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil et 3 personnes ressources); Centralisation et traitement des fiches par commune; Validation des CEV avec les acteurs locaux (Traitement des erreurs sur place) Liste définitive par commune NOMBRE DE CEV PAR REGION Région Nombre de CEV AGADEZ 765 TAHOUA 3372 DOSSO 2398 TILLABERY 3742 18 400 DIFFA 912 MARADI 3241 ZINDER 3788 NIAMEY 182 ETRANGER 247 TOTAL 18 647 Plan de Déploiement Plan de Déploiement couvrir tous les 18 647 CEV : Sur une superficie de 1 267 000 km2 Avec une population électorale attendue de 9 751 462 Et 3 500 kits (3000 kits fixes et 500 tablettes) ❖ KIT = Valise d’enrôlement constitués de plusieurs composants (PC ou Tablette, lecteur d’empreintes digitales, appareil photo, capteur de signature, scanner, etc…) Le pays est divisé en 2 zones d’intervention (4 régions chacune) et chaque région en 5 aires. -

Télécharger Le Rapport EIES Bazaga

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE ET DE L’ELEVAGE PROJET D’APPUI A L’AGRICULTURE SENSIBLE AUX RISQUES CLIMATIQUES PASEC RAPPORT D’ETUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL DU SPIC-AIC DANS LA COMMUNE RURALE DE BAZAGA (REGION DE TAHOUA) : AMENAGEMENT DE 25 HA DE PETITS PERIMETRES, DE LA MARE DE ROUAFI ET FONÇAGE D’UN FORAGE MOYEN EQUIPE D’EXHAURE SOLAIRE PAR HA RAPPORT DEFINITIF AVRIL 2020 TABLE DES MATIERES SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS .................................................... V LISTE DES TABLEAUX ........................................................... VI LISTE DES CARTES ............................................................... VII LISTE DES FIGURES ............................................................. VIII LISTE DES PHOTOS ............................................................... IX RESUME NON TECHNIQUE .................................................... X INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 1 1 DESCRIPTION COMPLETE DES ACTIVITES DE SOUS- PROJET ............................................................................ 3 1.1 Contexte et justification ........................................................... 3 1.2 Objectifs..................................................................................... 3 1.3 Activités prévues ...................................................................... 4 1.3.1 Aménagement des petits périmètres irrigués ....................... 4 1.3.2 Aménagement de la mare de Rouafi -

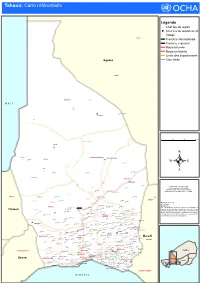

Ref Tahoua A1.Pdf

Tahoua: Carte référentielle Légende Chef lieu de région Chef lieu de département ! Village ARLIT Frontière internationale Frontière régionale Route bitumée Route en latérite Limite des départements Agadez Cour d'eau INGAL TASSARA Tassara M A L I Tezalite ! Nakonawa Sami ! TASSARA Tillia 0 25 50 75 kms Tchin Tabaradene TILLIA Chinwaren TCHINTABARADENE TCHIN TABARADEN ! Agando TILLIA ! Abalak Intikane ! Télemsès Efeinatas ! Amerkay ! . ! Assagueiguei ! ABALAK Kao ABALAK ! Taza ! Tamaya Creation Date: 20 Février 2015 Kao Assas ! Projection/Datum: GSC/WGS84 Web Resources: www.unocha.org/niger Haringué Ibessetene ! ! Akoubounou Nominal Scale at A1 paper size: 1: 750 000 Affala Tabalak Takanamat Takanamat Akarzaza ABALA ! Kafate ! Tabalak ! Barmou ! In Lelou BERMO ! In Aouara Alagaza ! ! In Najin Takanamat ! Toumfafi Map data source(s): ! OCHA Niger Ibazaouane ! DjiguinaLoudou Karkamat Disclaimers: TAHOUA Koureya ! ! ! ! Tahoua I et II Tahoua ! The designations employed and the presentation of I-n-Safari KardagaDafan Kaloma Kalfou Azeye Tebaram ! ! ! Kounkouzout material on this map do not imply the expression of any Tillaberi ! ! Ibohamane Labandam ! opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Tebaram In Karkada Kalfou Sokolé ! Edir ! ! Tchingaran ! Sabon GariAlibou Keita Ibohamane Gadamata Aliou ! United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, ! ! ! ! ! Tagatil territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the May Farin Kay Founkouey KEITA Bargat ! ! ! Kéda ! Toudou KEITA ! Zango Amadou delimitation -

Niger Education and Community Strengthening (NECS) Quarterly Narrative Report No

Niger Education and Community Strengthening (NECS) Quarterly Narrative Report No. 4, April - June 2013 And Year 1 Annual Report 1 Table of Contents List of Accronyms …………………………………………………………………...…. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………..….... 4 Context of Implementation ………………………………………………………...….... 4 I. General Overview …………………………………………………….......… 7 a. Political & Security Situation……………………………………...….… 7 b. Key Program Highlights ……………………………………….…...…... 8 II. Current Quarter Activities ……………………………………….……..…... 8 a. Strategic Objective 1: Increase access to quality education at project schools. …………………………………………………………………. 8 b. Strategic Objective 2 : Increased student grade reading achievement ... 18 c. Monitoring and Evaluation ……………………………………………. 20 III. Quarterly Financial Report (April-June 2013) ……………………………. 22 IV. Next Quarter Commitments and Expenditures ………………….……….... 22 V. Activities Planned for Next Quarter …………………………….………… 22 2 LIST OF ACRONYMS AeA Aide et Action AME Students’ Mothers Association ANED Nigerian Association for Education and Development AOR Agreement Officer Representative APE Students’ Parents Association (equivalent to PTA) CGDES School Management Committees (Used to be called COGES) COP Chief of Party CRC Child Right Convention DGEB Direction Générale de l’Enseignement de Base DPSF Directorate for the Promotion of Education of Girls DREN Regional Directos of Education EGRA Early Grade Reading Association EIE Initial Environmental Evaluation EMMP Environmental Measures and Mitigation Plan FCC Communal -

NER Zones De Couverture Programme Spotlight

NIGER Tillabéri - Initiative Spotlight Programme Niger - Communes d’intervention 2019-2022* Janvier 2019 Abala Sanam MALI Tondikiwindi MAI TALAKIA Anzourou Inatès Banibangou TALCHO Banibangou KOUFFEY Filingué Abala Ouallam TIDANI Abala BANIZOUMBOU Ayerou FAZAOU Sanam Dingazi TillabériAyerou GARBEY MALO KOIRA TOUNFALIS Sakoïra KOIRA TEGUI Tondikiwindi Gorouol DABRE CHICAL CHANYASSOU Sinder Ouallam SARGANE TILLAKAINA KOIRA ZENO Filingué KABIA Anzourou KOSSEY MAI TALAKIA BAGDAD GAOBANDA GUESSE HASSOU DINGAZI BANDA GARIE Tillabéri GOUTOUMBOU GOUROUKE Kourfeye Centre LOUMA TALCHO Bankilaré DAIBERI Dessa DIEP BERI KOUFFEY SIMIRI KANDA Bankilaré GANDOU BERI Ouallam TIDANI BANIZOUMBOU Filingué MORIBANE TASSI DEYBANDA ITCHIGUINE Bibiyergou FAZAOU TOMBO Méhana Simiri Dingazi Imanan KOKOMANI HAOUSSA Sakoïra Tondikandia BONKOUKOU SHETT FANDOU ET GOUBEY Tillabéri TOUNFALIS Kourteye GARBEY MALO KOIRA DALWAY EGROU KOIRA TEGUI MARIDOUMBOU Ouallam LOKI DABRE CHICAL CHANYASSOU LOSSA KADO SARGANE KRIP BANIZOUMBOU SIGUIRADO Sinder TILLAKAINA KOIRA ZENO Filingué Kokorou HASSOU KABIA GAOBANDA GUESSE KOSSEY Gothèye GARIE Tillabéri SANSANE HAOUSSA BAGDAD DINGAZI BANDA GARDAMA KOIRA GOUTOUMBOU GOUROUKE Kourfeye Centre DAIBERI LOUMA DIEP BERI SIMIRI BANIZOUMBOU KANDA TIBEWA (DODO KOIRA) Téra GOUNOU BANGOU ZONGO AGGOU GANDOU BERI JIDAKAMAT MORIBANE KORIA HAOUSSA TONDIGAMEYE ITCHIGUINE Karma KONE BERI ZAGAGADAN Téra TASSI DEYBANDA KORIA GOURMA BANNE BERI Imanan TOMBO KOKOMANI HAOUSSA Hamdallaye Simiri Balleyara BONKOUKOU NAMARO NIAME Tondikandia SHETT FANDOU ET