Marta Oracz Mauritius — the Paradise Island?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'histoire D'un Combat

L’histoire d’un combat MMM 1969 - 1983 En hommage à ces milliers de militants anonymes pour qui, toujours, la lutte continue... Matraqué par la Riot Unit lors d'une grève au ga- rage de l'UBS, à Bell Village, en août 1971, Paul Béren- ger, le visage en- sanglanté, sort de la Cour de 2ème Division. CHAPITRE I La lutte recommence E passé est le phare qui éclaire l'avenir. C'est pourquoi les L Mauriciens doivent en prendre connaissance pour mieux maîtriser leur destin. Le passé du Mouvement Militant Mauricien est indissociable de la lutte des travailleurs, ceux des champs, des usines et des bureaux, depuis près de 14 ans. Passé combien glorieux! C'est un passé marqué par le sceau indélébile d'une nouvelle force, jeune et dynamique, qui a donné à un pays, hier déses- péré, des raisons pour combattre, qui a combattu avec acharne-: ment pour des idées nouvelles et généreuses — qui a peut-être commis des erreurs — mais qui, par-dessus tout, a voulu d'une île Maurice plus juste, plus humaine et plus fraternelle. En septembre 1969 naissait le Mouvement Militant Mauricien M.M.M.). Afin que l'histoire de Maurice s'accomplisse. Afin de reprendre la lutte menée en d'autres temps par Anqetil, Rozemont, Pandit Sahadeo, Curé et d'autres Mauriciens socialistes. Pour le M.M.M., tout commence par le Club des Étudiants qui deviendra, en une décennie, la plus grande force politique nationale. Tout commence par ce jeune homme timide qui, au fil des années, saura faire naître de si grandes espérances dans le coeur de la nation. -

THE FORMATION, COLLAPSE and REVIVAL of POLITICAL PARTY COALITIONS in MAURITIUS Ethnic Logic and Calculation at Play *

VOLUME 4 NO 1 133 THE FORMATION, COLLAPSE AND REVIVAL OF POLITICAL PARTY COALITIONS IN MAURITIUS Ethnic Logic and Calculation at Play * By Denis K Kadima and Roukaya Kasenally ** Denis K Kadima is the Executive Director of EISA. P O Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 Johannesburg Tel: +27 (0) 11 482.5495; Fax: +27 (0) 11 482.6163 e-mail: [email protected] Dr Roukaya Kasenally is a media and political communication specialist and teaches in the Faculty of Social Studies and Humanities at the University of Mauritius. Reduit, Mauritius Tel: +230 454 1041; Fax: +230 686 4000 e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Coalitions and alliances are a regular feature of the Mauritian political landscape. The eight post-independence general elections have all been marked by electoral accords where those expecting to retain power or those aspiring to be in power hedge their bets by forming alliances with partners that ensure that they will be elected. Another fascinating feature is that, apart from that in 1976, all these coalitions have been formed before the election, allowing each party leader to engage in a series of tactical and bargaining strategies to ensure that his party gets a fair deal and, more recently, an equal deal, where the alliance partners shared the post of Prime Minister. The purpose of this paper is to shed some light on this under- researched area and to offer some explanation of the different mechanisms that exist * The authors acknowledge with gratitude the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Johannesburg, and the Embassy of Finland, Pretoria, who funded the project. -

'The Most Cosmopolitan Island Under the Sun'

‘The Most Cosmopolitan Island under the Sun’? Negotiating Ethnicity and Nationhood in Everyday Mauritius Reena Jane Dobson Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Cultural Research University of Western Sydney December 2009 The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. Reena Dobson Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my grandmother, my Nani, whose life could not have been more different from my own. I will always be grateful that I was able to grow up knowing her. I also dedicate this thesis to my parents, whose interest, support and encouragement never wavered, and who were always there to share stories and memories and to help make the roots clearer. Acknowledgements At the tail end of a thesis journey which has involved entangled routes and roots, I would like to express my deepest and most heartfelt thanks to my wonderful partner, Simon White, who has been living the journey with me. His passionate approach to life has been a constant inspiration. He introduced me to good music, he reminded me to breathe, he tiptoed tactfully around as I sat in writing mode, he made me laugh when I wanted to cry, and he celebrated every writing victory – large and small – with me. I am deeply indebted to my brilliant supervisors, Associate Professor Greg Noble, Dr Zoë Sofoulis and Associate Professor Brett Neilson, who have always been ready with intellectual encouragement and inspiring advice. -

MAURITIUS Date of Elections: 21 August 1983 Purpose of Elections

MAURITIUS Date of Elections: 21 August 1983 Purpose of Elections Elections were held for all the popularly-elected seats in Parliament following premature dissolution of this body on 17 June 1983. General elections had previously been held one year earlier, in June 1982. Characteristics of Parliament The unicameral Parliament of Mauritius, the Legislative Assembly, comprises 70 members: 62 members elected by universal adult suffrage and 8 "additional" members (the most successful losing candidates) appointed by an electoral commission to balance the representation of ethnic communities in Parliament. The term of the Assembly is 5 years. Electoral System All British Commonwealth citizens aged 18 or more who have either resided in Mauritius for not less than two years or are domiciled and resident in the country on a prescribed date may be registered as electors in their constituency. Not entitled to be registered, however, are the insane, persons guilty of electoral offences, and persons under sentence of death or serving a sentence of imprisonment exceeding 12 months. Electoral registers are revised annually. Proxy voting is allowed for members of the police forces and election officers on duty during election day, as well as for any duly nominated candidates. Voting is not compulsory. Candidates for the Legislative Assembly must be British Commonwealth citizens of not less than 18 years of age who have resided in Mauritius for a period of at least two years before the date of their nomination (and for six months immediately before that date) and who are able to speak and read the English language with a degree of proficiency sufficient to enable them to take an active part in the proceedings of the Assembly. -

BTI 2012 | Mauritius Country Report

BTI 2012 | Mauritius Country Report Status Index 1-10 8.11 # 17 of 128 Political Transformation 1-10 8.53 # 15 of 128 Economic Transformation 1-10 7.68 # 20 of 128 Management Index 1-10 6.99 # 9 of 128 scale: 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2012. The BTI is a global assessment of transition processes in which the state of democracy and market economy as well as the quality of political management in 128 transformation and developing countries are evaluated. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2012 — Mauritius Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2012. © 2012 Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh BTI 2012 | Mauritius 2 Key Indicators Population mn. 1.3 HDI 0.728 GDP p.c. $ 13671 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.5 HDI rank of 187 77 Gini Index - Life expectancy years 73 UN Education Index 0.659 Poverty3 % - Urban population % 42.6 Gender inequality2 0.353 Aid per capita $ 122.0 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2011 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2011. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary The 2010 general elections served as further proof of Mauritius’s functioning democracy. Furthermore, Mauritius’s calm and safe passage through the rough waters of the global economic and financial crisis in the past three years has shown the robustness of its economy and its high level of diversification. -

(Hansard) First Session Wednesday 07 December 2011

1 No. 35 of 2011 FIFTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) FIRST SESSION WEDNESDAY 07 DECEMBER 2011 2 CONTENTS PAPERS LAID QUESTION (ORAL) MOTION BILL (Public) ADJOURNMENT 3 Members Members THE CABINET (Formed by Dr. the Hon. Navinchandra Ramgoolam) Dr. the Hon. Navinchandra Ramgoolam, GCSK, Prime Minister, Minister of Defence, Home FRCP Affairs and External Communications Dr. the Hon. Ahmed Rashid Beebeejaun, GCSK, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Energy and FRCP Public Utilities Hon. Charles Gaëtan Xavier-Luc Duval, GCSK Vice-Prime Minister, Minister of Finance and Economic Development Hon. Anil Kumar Bachoo, GOSK Vice-Prime Minister, Minister of Public Infrastructure, National Development Unit, Land Transport and Shipping Dr. the Hon. Arvin Boolell, GOSK Minister of Foreign Affairs, Regional Integration and International Trade Dr. the Hon. Abu Twalib Kasenally, FRCS Minister of Housing and Lands Hon. Mrs Sheilabai Bappoo, GOSK Minister of Social Security, National Solidarity and Reform Institutions Dr. the Hon. Vasant Kumar Bunwaree Minister of Education and Human Resources Hon. Satya Veyash Faugoo Minister of Agro-Industry and Food Security Hon. Devanand Virahsawmy, GOSK Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development Dr. the Hon. Rajeshwar Jeetah Minister of Tertiary Education, Science, Research and Technology Hon. Tassarajen Pillay Chedumbrum Minister of Information and Communication Technology Hon. Louis Joseph Von-Mally, GOSK Minister of Fisheries and Rodrigues Hon. Satyaprakash Ritoo Minister of Youth and Sports Hon. Louis Hervé Aimée Minister of Local Government and Outer Islands Hon. Mookhesswur Choonee Minister of Arts and Culture Hon. Shakeel Ahmed Yousuf Abdul Razack Mohamed Minister of Labour, Industrial Relations and Employment Hon. Yatindra Nath Varma Attorney General 4 Hon. -

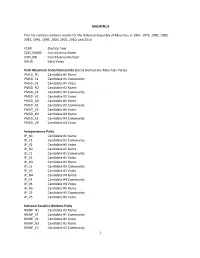

1 MAURITIUS This File Contains Election Results for the National

MAURITIUS This file contains election results for the National Assembly of Mauritius in 1967, 1976, 1982, 1983, 1987, 1991, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2014. YEAR Election Year CON_NAME Constituency Name CON_NO Constituency Number VALID Valid Votes Parti Mauricien Social Democrate (Social Democratic Mauritian Party) PMSD_N1 Candidate #1 Name PMSD_C1 Candidate #1 Community PMSD_V1 Candidate #1 Votes PMSD_N2 Candidate #2 Name PMSD_C2 Candidate #2 Community PMSD_V2 Candidate #2 Votes PMSD_N3 Candidate #3 Name PMSD_C3 Candidate #3 Community PMSD_V3 Candidate #3 Votes PMSD_N4 Candidate #4 Name PMSD_C4 Candidate #4 Community PMSD_V4 Candidate #4 Votes Independence Party IP_N1 Candidate #1 Name IP_C1 Candidate #1 Community IP_V1 Candidate #1 Votes IP_N2 Candidate #2 Name IP_C2 Candidate #2 Community IP_V2 Candidate #2 Votes IP_N3 Candidate #3 Name IP_C3 Candidate #3 Community IP_V3 Candidate #3 Votes IP_N4 Candidate #4 Name IP_C4 Candidate #4 Community IP_V4 Candidate #4 Votes IP_N5 Candidate #5 Name IP_C5 Candidate #5 Community IP_V5 Candidate #5 Votes National Socialist Workers Party NSWP_N1 Candidate #1 Name NSWP_C1 Candidate #1 Community NSWP_V1 Candidate #1 Votes NSWP_N2 Candidate #2 Name NSWP_C2 Candidate #2 Community 1 NSWP_V2 Candidate #2 Votes NSWP_N3 Candidate #3 Name NSWP_C3 Candidate #3 Community NSWP_V3 Candidate #3 Votes Mauritius Young Communist League MYCL_N1 Candidate #1 Name NYCL_C1 Candidate #1 Community MYCL_V1 Candidate #1 Votes Mauritius Liberation Front MLF_N1 Candidate #1 Name MLF_C1 Candidate #1 Community MLF_V1 Candidate -

Droolk Economic Development Institute

9089 droolkEconomic Development Institute of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Successful Stabilization Public Disclosure Authorized and Recovery in Mauritius Ravi Gulhati Public Disclosure Authorized and Raj Nallari Public Disclosure Authorized EDI DEVELOPMENT POLICY CASE SERIES Analytical Case Studies * Number 5 EDI DEVmoPMNrPoucy CASESRES ANAL.xcALCASE STUDmms * No. 5 Successful Stabilization and Recovery in Mauritius Ravi Gulhati Raj Nallari The World Bank Washington, D.C. Copyright 0 1990 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First printing September 1990 The Economic Development Institute (EDI) was established by the World Bank in 1955 to train officials concerned with development planning, policymaking, investment analysis, and project implementation in member developing countries. At present the substance of the EDrs work emphasizes macroeconomic and sectoral economic policy analysis. Through a variety of courses, seminars, and workshops, most of which are given overseas in cooperation with local institutions, the EDI seeks to sharpen analytical skills used in policy analysis and to broaden understanding of the experience of individual countries with economic development. In addition to furthering the EDI's pedagogical objectives, Policy Seminars provide forums for policymakers, academics, and Bank staff to exchange views on current development issues, proposals, and practices. Although the EDrs publications are designed to support its training activities, many are of interest to a much broader audience. EDI materials, including any findings, interpretations, and conclusions, are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. -

Constitutions, Cleavages and Coordination a Socio-Institutional Theory of Public Goods Provision

CONSTITUTIONS, CLEAVAGES AND COORDINATION A SOCIO-INSTITUTIONAL THEORY OF PUBLIC GOODS PROVISION by Joel Sawat Selway A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Professor Robert J. Franzese, Co-Chair Associate Professor Allen D. Hicken, Co-Chair Professor Ken Kollman Professor Mark Mizruchi Professor Ashutosh Varshney © Joel Sawat Selway 2009 Devotion To my mother, Savitree (Busparoek) Selway, for her tireless efforts to educate me as a child and the inspiration she left behind. ii Acknowledgements To God who has directed me in this path and blessed me with strength to see it through. To my wife who has selflessly supported me these long years in graduate school. To my children who gave me joy when I came home each day. To my advisor and co-chair, Allen Hicken, who convinced me to come to Michigan, who trained me in field research in Thailand, who tirelessly listened to and engaged my ideas, and who became my life-long friend. To Rob Franzese, my other co-chair and guru of stats, who respected my ideas, provided invaluable insights to help me develop them, and who gave of his time to read over my many drafts. It was in Rob’s Political Economy pro-seminar that I came upon the idea for my dissertation. To Ashutosh Varshney, for whom I have the upmost respect. Bringing me on to his research project in my first year of graduate school and with whom I worked for three years, Ashu inspired the development and ethnicity aspects of my dissertation, and encouraged me through his sincere praise and frank appraisals of my work. -

Debate No 01 of 2014 (UNREVISED)

1 No. 01 of 2014 FIFTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) THIRD SESSION FRIDAY 04 JULY 2014 (UNREVISED) 2 CONTENTS PROCLAMATION DEPUTY SPEAKER - ELECTION DEPUTY CHAIRMAN OF COMMITTEES - ELECTION PAPERS LAID MOTION BILL (Public) ADJOURNMENT 3 Members Members THE CABINET (Formed by Dr. the Hon. Navinchandra Ramgoolam) Dr. the Hon. Navinchandra Ramgoolam, Prime Minister, Minister of Defence, Home Affairs and GCSK, FRCP External Communications, Minister of Finance and Economic Development, Minister for Rodrigues Dr. the Hon. Ahmed Rashid Beebeejaun, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Energy and Public GCSK, FRCP Utilities Hon. Anil Kumar Bachoo, GOSK Vice-Prime Minister, Minister of Public Infrastructure, National Development Unit, Land Transport and Shipping Dr. the Hon. Arvin Boolell, GOSK Minister of Foreign Affairs, Regional Integration and International Trade Dr. the Hon. Abu Twalib Kasenally, Minister of Housing and Lands GOSK, FRCS Hon. Mrs Sheilabai Bappoo, GOSK Minister of Social Security, National Solidarity and Reform Institutions Dr. the Hon. Vasant Kumar Bunwaree Minister of Education and Human Resources Hon. Satya Veyash Faugoo, GOSK Minister of Agro-Industry and Food Security, Attorney- General Hon. Devanand Virahsawmy, GOSK Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development Dr. the Hon. Rajeshwar Jeetah Minister of Tertiary Education, Science, Research and Technology Hon. Tassarajen Pillay Chedumbrum Minister of Information and Communication Technology Hon. Louis Joseph Von -Mally, GOSK Minister of Fisheries Hon. Satyaprakash Ritoo Minister of Youth and Sports Hon. Louis Hervé Aimée Minister of Local Government and Outer Islands Hon. Mookhesswur Choonee, GOSK Minister of Arts and Culture Hon. Shakeel Ahmed Yousuf Abdul Minister of Labour, Industrial Relations and Razack Mohamed Employment Hon. -

(Hansard) First Session Tuesday 28 June 2011

1 No. 14 of 2011 FIFTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) FIRST SESSION TUESDAY 28 JUNE 2011 2 CONTENTS PAPERS LAID QUESTIONS (ORAL) MOTION STATEMENT BY MINISTER BILLS (Public) ADJOURNMENT QUESTIONS (written) Members Members THE CABINET 3 (Formed by Dr. the Hon. Navinchandra Ramgoolam) Dr. the Hon. Navinchandra Ramgoolam, GCSK, Prime Minister, Minister of Defence, Home Affairs FRCP and External Communications Dr. the Hon. Ahmed Rashid Beebeejaun, GCSK, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Energy and FRCP Public Utilities Hon. Charles Gaëtan Xavier-Luc Duval, GCSK Vice-Prime Minister, Minister of Social Integration and Economic Empowerment Hon. Pravind Kumar Jugnauth Vice-Prime Minister, Minister of Finance and Economic Development Hon. Anil Kumar Bachoo, GOSK Minister of Public Infrastructure, National Development Unit, Land Transport and Shipping Dr. the Hon. Arvin Boolell, GOSK Minister of Foreign Affairs, Regional Integration and International Trade Dr. the Hon. Abu Twalib Kasenally, FRCS Minister of Housing and Lands Hon. Mrs Sheilabai Bappoo, GOSK Minister of Gender Equality, Child Development and Family Welfare Hon. Nandcoomar Bodha Minister of Tourism and Leisure Dr. the Hon. Vasant Kumar Bunwaree Minister of Education and Human Resources Hon. Satya Veryash Faugoo Minister of Agro-Industry and Food Security Hon. Showkutally Soodhun Minister of Industry and Cooperatives Hon. Devanand Virahsawmy, GOSK Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development Dr. the Hon. Rajeshwar Jeetah Minister of Tertiary Education, Science, Research and Technology 4 Hon. Satyaprakash Ritoo Minister of Youth and Sports Hon. Mrs Leela Devi Dookun-Luchoomun Minister of Social Security, National Solidarity and Reform Institutions Hon. Louis Hervé Aimée Minister of Local Government and Outer Islands Hon. -

Operation Lal Dora: India's Aborted Military Intervention in Mauritius

Operation Lal Dora: India’s aborted military intervention in Mauritius Mauritius forms an anchor to India’s strategic role in the Indian Ocean. India has long had a special economic, political and security relationship with Mauritius, which a US diplomatic report has characterised as Mauritius’ “willing subordination” to India.1 A key turning point in the relationship occurred in 1983, when, in Operation Lal Dora, India came to the point of a full scale military intervention in the island state to ensure that it stayed in India’s strategic orbit. This article will discuss a 1983 political crisis in Mauritius which threatened to overturn a Hindu-led government and led to plans for an Indian intervention in the island. When Indian military leaders hesitated over a military operation, Indira Gandhi instead relied on her security services to achieve India’s objectives. An understanding of this previously undisclosed operation casts light on India’s thinking about its role in the region, its military decision-making processes, and on what could be seen as a long-standing alignment of interests between India and the United States in the Indian Ocean. These issues are particularly relevant as the United States now looks to further develop its strategic partnership with India as part of its ‘Pivot to Asia’. Strategic rivalry in the Indian Ocean during the Cold War The southwest Indian Ocean of the late 1970s and early 1980s was a scene of superpower competition, rivalry and intrigue. The Indian Ocean had become a new frontier of the Cold 1 War as the Soviet Union and the United States expanded their naval capabilities in the region and jostled for influence over the small and politically weak Indian Ocean island states.