Creation and Liberating Failure in Robert Coover’S the Universal 228 Baseball Association Iii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O Klahoma City

MEDIA GUIDE O M A A H C L I K T Y O T R H U N D E 2 0 1 4 2 0 1 5 THUNDER.NBA.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ALL-TIME RECORDS General Information .....................................................................................4 Year-By-Year Record ..............................................................................116 All-Time Coaching Records .....................................................................117 THUNDER OWNERSHIP GROUP Opening Night ..........................................................................................118 Clayton I. Bennett ........................................................................................6 All-Time Opening-Night Starting Lineups ................................................119 2014-2015 OKLAHOMA CITY THUNDER SEASON SCHEDULE Board of Directors ........................................................................................7 High-Low Scoring Games/Win-Loss Streaks ..........................................120 All-Time Winning-Losing Streaks/Win-Loss Margins ...............................121 All times Central and subject to change. All home games at Chesapeake Energy Arena. PLAYERS Overtime Results .....................................................................................122 Photo Roster ..............................................................................................10 Team Records .........................................................................................124 Roster ........................................................................................................11 -

Completing the Circle: Native American Athletes Giving Back to Their Community

University of Tennessee, Knoxville Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2019 COMPLETING THE CIRCLE: NATIVE AMERICAN ATHLETES GIVING BACK TO THEIR COMMUNITY Natalie Michelle Welch University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Welch, Natalie Michelle, "COMPLETING THE CIRCLE: NATIVE AMERICAN ATHLETES GIVING BACK TO THEIR COMMUNITY. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5342 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPLETING THE CIRCLE: NATIVE AMERICAN ATHLETES GIVING BACK TO THEIR COMMUNITY A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Natalie Michelle Welch May 2019 Copyright © 2019 by Natalie Michelle Welch All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my elders and ancestors. Without their resilience I would not have the many great opportunities I have had. Also, this is dedicated to my late best friend, Jonathan Douglas Davis. Your greatness made me better. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank the following people for their help through my doctoral program and the dissertation process: My best friend, Spencer Shelton. This doctorate pursuit led me to you and that’s worth way more than anything I could ever ask for. Thank you for keeping me sane and being a much-needed diversion when I’m in workaholic mode. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

The Novel's Anxieties Over Existence, Purpose, and Believability

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State English Theses English 8-2012 Survival of the Fictiveness: The oN vel’s Anxieties Over Existence, Purpose, and Believability Jesse Mank Buffalo State College, [email protected] Advisor Dr. Aimable Twagilimana, Professor of English First Reader Dr. Barish Ali, Assistant Professor of English Department Chair Dr. Ralph L. Wahlstrom, Associate Professor of English To learn more about the English Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to http://english.buffalostate.edu/. Recommended Citation Mank, Jesse, "Survival of the Fictiveness: The oN vel’s Anxieties Over Existence, Purpose, and Believability" (2012). English Theses. Paper 5. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/english_theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Survival of the Fictiveness: The Novel’s Anxieties Over Existence, Purpose, and Believability by Jesse Mank An Abstract of a Thesis in English Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2012 State University of New York College at Buffalo Department of English Mank i ABSTRACT OF THESIS Survival of the Fictiveness: The Novel’s Anxieties Over Existence, Purpose, and Believability The novel is a problematic literary genre, for few agree on precisely how or why it rose to prominence, nor have there ever been any strict structural parameters established. Terry Eagleton calls it an “anti-genre” that “cannibalizes other literary modes and mixes the bits and pieces promiscuously together” (1). And yet, perhaps because of its inability to be completely defined, the novel best represents modern thought and sensibility. -

Literary Tricksters in African American and Chinese American Fiction

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2000 Far from "everybody's everything": Literary tricksters in African American and Chinese American fiction Crystal Suzette anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the Ethnic Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Crystal Suzette, "Far from "everybody's everything": Literary tricksters in African American and Chinese American fiction" (2000). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623988. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-z7mp-ce69 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Lives from Death Row: Common Sinners and Current Pasts

Moats, B 2019 Lives From Death Row: Common Sinners and Current Pasts. Anthurium, 15(2): 9, 1–9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33596/anth.383 ARTICLE Lives From Death Row: Common Sinners and Current Pasts Ben Moats The University of Miami and Exchange for Change, US [email protected] This analysis interrogates Mumia Abu-Jamal’s Live From Death Row to argue that unlike traditional personal narratives or memoirs, the diverse series of vignettes in Abu-Jamal’s most famous publication provoke readers to grapple not solely with his lived experiences on death row or the lived experiences of his fellow inmates; they also call for readers to confront the damming moral, social, and economic impact of mass incarceration on society at large. His internal account of prison life, therefore, depicts the inmates of Pennsylvania’s Huntingdon County prison not as moral aliens but as human beings and what early New England execution sermons describe as “common sinners.” More specifically, Abu-Jamal’s arguments linking the “free” with the condemned work on two basic levels. First and foremost, they illuminate the ways we all share a common history of racism by implicitly revealing the connections between slavery, Dred Scott, Plessey v. Ferguson, Jim Crow, the civil rights movement, McCleskey v. Kemp, and the ideological prejudices that still permeate and influence our legal, political, and social systems today. Thus, given Abu-Jamal’s compassionate internal account of prison life; his analysis of the all-to-frequent harsh realities of our justice system; as well as his common-sense plea for reform, this analysis contends that Live From Death Row continues to speak with more contemporary works like Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, Netflix’s 13th, Angela Y. -

Deconstruction of Peter Pan's Character in Edward Kitsis' And

Deconstruction of Peter Pan’s Character in Edward Kitsis’ and Adam Horowitz’s Once Upon a Time, Season Three (2013) - Alya Safira (p.10-21) 10 Deconstruction of Peter Pan’s Character in Edward Kitsis’ and Adam Horowitz’s Once Upon a Time, Season Three (2013) Alya Safira1, Eni Nur Aeni2, Mimien Aminah Sudja’ie3 Department of English Language and Literature, Jenderal Soedirman University [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Article History: Abstract. The purpose of this research is to find out the First Received: deconstruction of Peter Pan’s character in Kitsis’ and Horowitz’s 21/05/2020 work as described in Barrie’s Peter Pan. Kitsis’ and Horowitz’s Once Upon a Time, Season Three is the first film that deconstructs the Final Revision: character of Peter Pan from Barrie’s Peter Pan. The qualitative 28/06/2020 method is used in analyzing the main data that are taken from both works, Barrie’s Peter Pan and Kitsis’ and Horowitz’s Once Upon a Available online: Time, Season Three. The data analysis starts by selecting the data 30/06/2020 from re-watching and re-reading the works. Then analyzing them using the theory of deconstruction, character and characterization and cinematography. The theory is used to find the binary opposition and analyzing the characteristics of Peter Pan in both works. The cinematography is also needed to support the analysis and strengthens the argument of the analysis from the character’s deconstruction. The result of the analysis shows that the characteristic of Peter Pan in Barrie’s Peter Pan is deconstructed from hero into villain. -

Yadv Entu Re Guides Story

Stories are used in The YMCA Ad- - Creates a feeling of low-stress STORY- venture Guides program in many enjoyment settings, including meetings, cam- - Makes memories that last TELLING pouts, adventures, and car trips. Stories are both enjoyable and STORYTELLING TIPS educational-they can convey a les- Before telling any story, ask your- son and encourage questions more self these three questions: effectively than more direct meth- 1. What do I want people to feel ods. In this section you’ll learn after they hear my story? more about the benefits of story- 2. What do I want people to re- telling, best practices for present- member from mystory? ing stories that engage and en- 3. What do I want people to be- tertain, some sample stories, and lieve as a result of hearing my sources to check for story ideas. story? BENEFITS OF STORYTELLING Once you know what your purpose We use stories to communicate is, you can begin to tell a memora- information and ideas. In stories, ble story. Settle the audience and words create pictures in the minds set up the story. Devise a strategy of The YMCA Adventure Guides to keep the group focused, use an that, when combines with a moral opening question, a prop, a calm- or value, make the concept easier ing song, or creatively dive into to grasp and remember. If the sto- the story such as a way that all ryteller is successful, great stories eyes and ears are on you. Consid- Y ADVENTURE GUIDES are remembered and repeated. er these factors that contribute to Successful storytelling within a the telling of the great story: YMCA Adventure Guides program produces the following results: Plot- has one central plot in your - Creates a common focus for the story, and keeps it simple. -

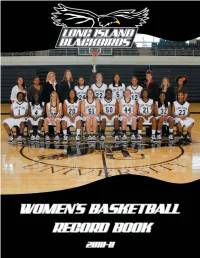

2010-11 Record Book

Radio/TV Chart 1••Kiara Evans 3••Marika Sprow 5••Desiree’ Simmons 15••Nicole Lentini 20••Ashley Palmer G••5-8••Jr. G••5-7••Jr. G••5-5••Fr. G••5-8••Fr. F••5-10•Jrr. Norcross, Ga. Trenton, N.J. Newark, N.J. Hazlet, N.J. Oxford, Pa. 21••Chelsi Johnson 22••Heidi Mothershead 23••She’tiarra Pledger 24••Krystal Wells 25••Cleandra Roberts F••6-0••Sr. G••5-7••Sr. G••5-7••Jr. G••5-5••So. G/F••6-0••Fr. Egg Harbor Twp., N.J. Hagerstown, Md. Kansas City, Kan. Douglasville, Ga. Miami, Fla. 32••Ify Obianwu 44••MaryAnn Abrams 50••Tamika Guz 51••Justine Stevenson F••6-0••So. F••6-1••Jr. C••6-2••So. F••5-11••Sr. Tabernacle, N.J. Garnerville., N.Y. Miami, Fla. Jackson, N.J. Media Information Game Day The media room is located in the southwest corner of the Wellness, Recreation and Athletic Center, off of the arena fl oor on the second level. Locker rooms are closed to the media. Interviews will be conducted in the media room or in an area designated by the media relations department. Press row seating at the Wellness Center is at fl oor level (north side) on the opposite side of the scorer’s table. Electrical power and phone lines are available for use. Programs, game notes and media guides will be available in the media room. There will be a pregame meal for the media in the media room approximately one hour before game time. -

Jewish Historical Society of Central Jersey

JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF CENTRAL JERSEY Winter 2008 NEWSLETTER Tevet/Shevat An Oral History of Congregation Etz Ahaim by Dr. Nathan Reiss Congregation Etz Ahaim is Sephardic, originally formed and also grateful to Congregation Etz Ahaim for providing in New Brunswick during the 1920s by Jewish immigrants the matching funds. from Salonika, which was formerly in Turkey and is now in Greece. Until the mid-1960s, the Congregation was com- As soon as we began deciding exactly who we were going to posed almost entirely of those original immigrants and their interview, it became apparent that there weren’t even close to descendants. Around that time, loss of the original members twenty persons left in the Congregation who had knowledge through death and relocation drastically diminished the size of its early history. That caused us to broaden our definition of the Congregation. By the early 80s, not much more than of what we were looking for, and we began to look at the rest a decade after its new building in Highland Park was built, of the Congregation, and what stories they might have. We the synagogue had difficulty in maintaining a minyan for quickly realized that the Congregation had literally become Shabbat services. a miniature United Nations, with Jews from a wide range of areas. So, in our synagogue Bulletin, we put out a call for Around that time, a new group of Sephardic Jews began to people who wanted to be interviewed. filter in: Jews who immigrated to the U.S. from the Middle East and from North Africa. -

Over 85 New Items!

PRSRT STD U.S. Postage P.O. Box 15388 Seattle, WA 98115 PAID www.gaelsong.com GaelSong customer number key code OVER 85 NEW ITEMS! NEW! Secret Knowledge u In the alchemist’s study, a skull sits atop a stack of books. What arcane knowledge do they hold? Lift the top Zipper Detail volume to reveal a hidden space for your secret treasure! Bronze-finished resin with handpainted touches of subtle color. 4½" tall x 4¾" wide, storage space is 2 x 3¼ x 1½". D24009 Skull and Books $40 Trinket Box Printed in USA on recycled paper (minimum post-consumer 10% waste). NEW! EssentiAl philoSophy u The Tree of Life illustrates the interconnectedness of all things—above and below, plants, animals and all beings. Welsh artist Jen Delyth’s depiction of this essential philosophy will inspire your thoughts in this Ivory Charcoal Marled Blue journal. Intricately-tooled green leather cover depicts the Tree of Life surrounded A little Zip to your life by branching knotwork. The classic texture of Irish knitting has fun in this zip-front Hand-laced leather binding hoodie cardigan. Warm and comfortable as a sweatshirt, but holds handmade paper pages. far more stylish, it sports a trinity-knot zipper pull for a final 300 pages; 5" x 7". Irish touch. In Green, Ivory, Charcoal or Marled Blue. Soft C14007 Tree of Life Leather Journal $50 100% merino wool, hand wash. Sizes S-XL. Made in Ireland. Celebrating the Celtic Imagination $ A20025 Women's Hoodie Zip Sweater 160 early autumn 2012 t age oF romance Magically transport yourself to a time of adventures and castles, sorcery and spell- casting, romance and chivalry. -

An Empathic Consideration of the Scapegoat in The

AN EMPATHIC CONSIDERATION OF THE SCAPEGOAT IN THE NOVELLAS OF STEPHEN CRANE AND HENRY JAMES __________________ A University Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, East Bay __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English __________________ By Jin Mee Leal June, 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Jin Mee Leal ii Abstract Late 19th century literature often responds to the anxieties of class, gender, and race by participating in justifying the hierarchies as it relies on a deterministic setting and typically explores the grimmer, but often realistic, themes in American life. Critics who maintain a Naturalist reading today take the time period into account and justify the characters’ reactions by considering them as victims of their severe environment. But what is ultimately disregarded with this sort of reading is human compassion and one’s inherent desire to help another. In examining Stephen Crane’s Maggie: A Girl of the Streets and “The Monster” as well as Henry James’ “Daisy Miller: A Study,” this thesis will argue that by having such harsh characters contrasted with caring (though fallen) characters, the concept of hierarchies and what is “natural” becomes problematized. By offering a new reading, contemporary readers may have a different viewpoint of what should be deemed as a justifiable action. With a more sympathetic reading, we may view these texts not just as a validation for this pessimistic literature, but texts that provide alternatives to how one could react in harsh situations. Crane and James offer the opportunity to question these social constructs and consider the unnaturalness of what has been previously deemed “natural.” We need to resist categorizing these important texts so that we can keep them alive and relevant.