Participation and Performance Trends in Ultra-Endurance Running Races

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Greek Society by Mark Cartwright Published on 15 May 2018

Ancient Greek Society by Mark Cartwright published on 15 May 2018 Although ancient Greek Society was dominated by the male citizen, with his full legal status, right to vote, hold public oce, and own property, the social groups which made up the population of a typical Greek city-state or polis were remarkably diverse. Women, children, immigrants (both Greek and foreign), labourers, and slaves all had dened roles, but there was interaction (oen illicit) between the classes and there was also some movement between social groups, particularly for second-generation ospring and during times of stress such as wars. The society of ancient Greece was largely composed of the following groups: male citizens - three groups: landed aristocrats (aristoi), poorer farmers (periokoi) and the middle class (artisans and traders). semi-free labourers (e.g the helots of Sparta). women - belonging to all of the above male groups but without citizen rights. children - categorised as below 18 years generally. slaves - the douloi who had civil or military duties. foreigners - non-residents (xenoi) or foreign residents (metoikoi) who were below male citizens in status. Classes Although the male citizen had by far the best position in Greek society, there were dierent classes within this group. Top of the social tree were the ‘best people’, the aristoi. Possessing more money than everyone else, this class could provide themselves with armour, weapons, and a horse when on military campaign. The aristocrats were oen split into powerful family factions or clans who controlled all of the important political positions in the polis. Their wealth came from having property and even more importantly, the best land, i.e.: the most fertile and the closest to the protection oered by the city walls. -

The Riddle of Ancient Sparta: Unwrapping the Enigma

29 May 2018 The Riddle of Ancient Sparta: Unwrapping the Enigma PROFESSOR PAUL CARTLEDGE (Sir Winston) Churchill once famously referred to Soviet Russia as ‘a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma’. My title is a simplified version of that seemingly obscure remark. The point of contact and comparison between ancient Sparta and modern Soviet Russia is the nature of the evidence for them, and the way in which they have been imagined and represented, by outsiders. There was a myth - or mirage – of ancient Sparta, as there was of Soviet Russia: typically, the outsider who commented was both very ignorant and either wildly PRO or – as in Churchill’s case – wildly ANTI. There was no moderate, middle way. The ‘Spartan Tradition’ (Elizabeth Rawson) is alive and – well, ‘well’ to this day. To start us off, I give you a relatively gentle, deliberately inoffensive and very British example of the PRO myth, mirage, legend or tradition of ancient Sparta. In 2017 Terry’s of York confectioners would have been celebrating its 150th anniversary, had it not been taken over by Kraft in 1993. A long discontinued but still long cherished Terry’s line was their ‘Spartan’ assortment: hard-centre chocolates, naturally. Because the Spartans were the ultimate ancient warriors, uber-warriors, if you like. And their fearsome reputation on the battlefield had won them not just respect but fame – and not just in antiquity: think only of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE – and of the movie 300. But of course the Spartans were no mere chocolate box soldiers - they were the real thing, the hard men of ancient Greece. -

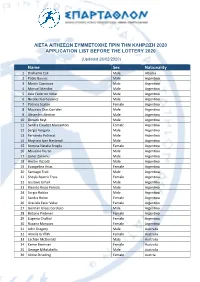

ΛΙΣΤΑ ΑΙΤΗΣΕΩΝ ΣΥΜΜΕΤΟΧΗΣ ΠΡΙΝ ΤΗΝ ΚΛΗΡΩΣΗ 2020 APPLICATION LIST BEFORE the LOTTERY 2020 (Updated 26/02/2020)

ΛΙΣΤΑ ΑΙΤΗΣΕΩΝ ΣΥΜΜΕΤΟΧΗΣ ΠΡΙΝ ΤΗΝ ΚΛΗΡΩΣΗ 2020 APPLICATION LIST BEFORE THE LOTTERY 2020 (Updated 26/02/2020) Name Sex Nationality 1 Dashamir Cali Male Albania 2 Pablo Barnes Male Argentina 3 Martín Casanova Male Argentina 4 Manuel Mendez Male Argentina 5 Jose Federico Vittar Male Argentina 6 Nicolas Kierdelewicz Male Argentina 7 Patricia Scalise Female Argentina 8 Mauricio Dias Corrales Male Argentina 9 Alejandro Almiron Male Argentina 10 Dimack Reyt Male Argentina 11 Sandra Elisabet Marcantoni Female Argentina 12 Sergio Vergara Male Argentina 13 Fernando Petracci Male Argentina 14 Mayricio Ivan Nesteruk Male Argentina 15 Romina Natalia Scoglia Female Argentina 16 Mauricio Duran Male Argentina 17 Javier Zannino Male Argentina 18 Hector Rizzotti Male Argentina 19 Evangelina Arias Female Argentina 20 Santiago Trull Male Argentina 21 Sheyla Beatriz Troia Female Argentina 22 Gustavo Ismail Male Argentina 23 Ricardo Rojas Peredo Male Argentina 24 Sergio Robles Male Argentina 25 Sandra Rolon Female Argentina 26 Graciela Ester Velez Female Argentina 27 Germán Ulises Cordisco Male Argentina 28 Betiana Pintener Female Argentina 29 Eugenia Challiol Female Argentina 30 Roxana Marques Female Argentina 31 John Gregory Male Australia 32 Amelia Griffith Female Australia 33 Lachlan McDonald Male Australia 34 Kerrie Bremner Female Australia 35 George Mihalakellis Male Australia 36 Ulrike Striednig Female Austria 37 Gerhard Schiemer Male Austria 38 Jesse Robbroeckx Male Belgium 39 Stefaan Wouters Male Belgium 40 Patrick Leysen Male Belgium 41 Chris Dhooge -

Lavaredo Ultra Ach Mar Spartathlon Eco Trail De

WORLD’S BEST RACES ← ← LAVAREDO ULTRA SPARTATHLON ECO TRAIL DE PARIS MONGOLIA SUNRISE ACHILL HALF SATARA HILL HALF THE LAUGAVEGUR TRAIL SEVILLE MARATHON With an 11pm start, One of the first – A ‘trail’ festival with TO SUNSET MARATHON MARATHON Come prepared for all Thanks to a new and almost 6,000m of and still among the a difference – it’s A singletrack 42km Achill is an island just Starting at 678m four seasons and improved route that gruelling ascent and toughest – ultra races held in an urban and 100km ultra off County Mayo in above sea level, constantly changing doesn’t rise more a 30-hour cut-off to in the world – only 40 metropolis, albeit one starting at sunrise on the west of Ireland. the route for this terrain on this trail than 10 metres above contend with (the per cent of the field of the most beautiful the shores of Lake It’s just about as far out-and-back race ultra, staged in the sea level, Seville is average finish time typically finish this cities in the world. Hovsgol in northern west as you can go held in the western southern highlands of the flattest marathon is 23 hours), you will 246km single-stage With over 6,000 Mongolia. You’ll run in Europe without Indian city of Satara is Iceland. The 55km in Europe. With have to live and race along roads, runners entering the through moss-laden getting your feet wet almost entirely uphill route is the perfect temperatures in breathe ultrarunning trails and footpaths four events on offer forests, windblown in the Atlantic – which until the halfway mark opportunity to race winter (such as it is) just to get to the start from Athens to (18/30/45/80km lowlands, rocky makes it every bit as (indeed, walking is through an other- hovering around 15C line of this 120km race Sparta. -

For the Long Distance Runner, the Spartathlon Is a Kind of Matterhorn

Spartathlon 2016 Race Report David Niblack For the long distance runner, the Spartathlon is a kind of Matterhorn. It has the ingredients of an epic: a finish line that stretches a long, long way from the start; 153 miles, almost six consecutive marathons. There is a big mountain at the 100 mile mark, a big city at the start, a big cold night in the middle, and a big percentage of runners who don’t make it. The race has international prestige and gathers runners from all corners of the world. To 1 top it off, the course claims a remarkable history. According to Herodotus, in 490 B.C the Athenian runner Philippides left Athens and arrived in Sparta the next day. His legendary run was for the purpose of asking the Spartans for help against the invading Persians before the conflict that would lead to the battle of Marathon. It was a run to save democracy, a run to save the foundations of Western culture. My entry into running was unexpected. The Chicago Marathon course paralleled my college campus and gave me the idea to give it a try. Previously, I thought runners were weird, always talking about their “training” and seeming to enjoy going out and running 20 miles – not normal! I reluctantly signed up for the marathon and finished seven minutes away from the Boston qualifying time. That tempted me to try to qualify, how cool to be able to run THE Boston Marathon. It took me two more marathons to 2 qualify. By that time, I was starting to enjoy (most of the time) training and the excitement of marathon day. -

Λιστα Αναμονησ - Waiting List 2020 International Athletes (07/04/2020)

ΛΙΣΤΑ ΑΝΑΜΟΝΗΣ - WAITING LIST 2020 INTERNATIONAL ATHLETES (07/04/2020) Surname Name Sex Nationality 1 DOROSZ MAREK Male POLAND 2 CSABRAK ANDRAS Male HUNGARY 3 MONEGATO PIER GIUSEPPE Male ITALY 4 HORAKOVA LENKA Female CZECH REPUBLIC 5 DEBIZE JEROME Male IRELAND 6 RICKLEFS CHAD Male U.S.A 7 FAN JUNG-HIS Male CHINESE TAIPEI 8 FIRTH ADAM Male UNITED KINGDOM 9 COLLINS EMILY Female U.S.A 10 DORNYEI ISTVAN Male HUNGARY KISHAZINE - 11 ZOMBORY ERIKA Female HUNGARY 12 ROOS HENRIK Male SWEDEN 13 OLDFIELD DEAN Male UNITED KINGDOM 14 STRACHAN DARREN Male UNITED KINGDOM 15 SAROSI GYULA Male HUNGARY 16 CHOU WEI-JEN Male CHINESE TAIPEI 17 TUSKE ZSOLT Male HUNGARY 18 SZABO PETER Male HUNGARY 19 RIZZOTTI HECTOR Male ARGENTINA 20 CATTELAN FRANCO Male ITALY 21 POWER SOPHIE Female UNITED KINGDOM 22 MITEV PIERRE Male FRANCE 23 PUSKALA LINA Female FINLAND 24 BORSOS JOZSEF Male HUNGARY 25 MOROCZA ANDREA Female HUNGARY 26 ROMANO STEFANO Male ITALY 27 RAVER NINA Female ISRAEL 28 CASTOLDI STEFANO Male ITALY 29 BELASKA PREMYSL Male CZECH REPUBLIC 30 THORUD MAGNUS Male NORWAY 31 CALZOLAI DAVID Male ITALY 32 WIGGINS PAUL Male UNITED KINGDOM 33 REMI DUBOQ Male FRANCE 34 PEDERSEN HANS RONN Male DENMARK 35 JACKSON THOMAS Male U.S.A 36 ROLON SANDRA Female ARGENTINA 37 UGALDE ASTEINZA JAVIER Male SPAIN 38 MOLINAS RIOS KARINA ALEJANDRA Female PARAGUAY 39 DIERX WILMA Female NETHERLANDS 40 SHIPLEY STUART Male UNITED KINGDOM 41 ADAMS PAUL Male UNITED KINGDOM 42 CARONI LUCIO Male ITALY 43 CRUZ BRENDA Female MEXICO 44 MIRANDA FERNANDO Male BRAZIL 45 FEGYVERESI JOHN Male U.S.A -

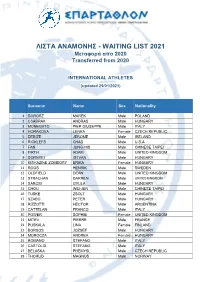

ΛΙΣΤΑ ΑΝΑΜΟΝΗΣ - WAITING LIST 2021 Μεταφορά Απο 2020 Transferred from 2020

ΛΙΣΤΑ ΑΝΑΜΟΝΗΣ - WAITING LIST 2021 Μεταφορά απο 2020 Transferred from 2020 INTERNATIONAL ATHLETES (updated 29/01/2021) Surname Name Sex Nationality 1 DOROSZ MAREK Male POLAND 2 CSABRAK ANDRAS Male HUNGARY 3 MONEGATO PIER GIUSEPPE Male ITALY 4 HORAKOVA LENKA Female CZECH REPUBLIC 5 DEBIZE JEROME Male IRELAND 6 RICKLEFS CHAD Male U.S.A 7 FAN JUNG-HIS Male CHINESE TAIPEI 8 FIRTH ADAM Male UNITED KINGDOM 9 DORNYEI ISTVAN Male HUNGARY 10 KISHAZINE ZOMBORY ERIKA Female HUNGARY 11 ROOS HENRIK Male SWEDEN 12 OLDFIELD DEAN Male UNITED KINGDOM 13 STRACHAN DARREN Male UNITED KINGDOM 14 SAROSI GYULA Male HUNGARY 15 CHOU WEI-JEN Male CHINESE TAIPEI 16 TUSKE ZSOLT Male HUNGARY 17 SZABO PETER Male HUNGARY 18 RIZZOTTI HECTOR Male ARGENTINA 19 CATTELAN FRANCO Male ITALY 20 POWER SOPHIE Female UNITED KINGDOM 21 MITEV PIERRE Male FRANCE 22 PUSKALA LINA Female FINLAND 23 BORSOS JOZSEF Male HUNGARY 24 MOROCZA ANDREA Female HUNGARY 25 ROMANO STEFANO Male ITALY 26 CASTOLDI STEFANO Male ITALY 27 BELASKA PREMYSL Male CZECH REPUBLIC 28 THORUD MAGNUS Male NORWAY 29 CALZOLAI DAVID Male ITALY 30 WIGGINS PAUL Male UNITED KINGDOM 31 REMI DUBOQ Male FRANCE 32 PEDERSEN HANS RONN Male DENMARK 33 JACKSON THOMAS Male U.S.A 34 ROLON SANDRA Female ARGENTINA 35 UGALDE ASTEINZA JAVIER Male SPAIN 36 MOLINAS RIOS KARINA ALEJANDRA Female PARAGUAY 37 DIERX WILMA Female NETHERLANDS 38 SHIPLEY STUART Male UNITED KINGDOM 39 ADAMS PAUL Male UNITED KINGDOM 40 CARONI LUCIO Male ITALY 41 CRUZ BRENDA Female MEXICO 42 MIRANDA FERNANDO Male BRAZIL 43 FEGYVERESI JOHN Male U.S.A 44 BOGNAR -

Beverley AC Runner Takes on Spartathlon Ultra Marathon 2013

Beverley AC runner takes on Spartathlon Ultra Marathon 2013 Blamires will be back Report by Andrew Grainger Beverley AC runner, Mike Blamires, likes his challenges big! Not content with having completed the gruelling Marathon Des Sables, with its 5 ½ marathons in 6 days in the Sahara Desert, or the 145 miles of the 2011 Grand Union Canal UltraMarathon, on 27th September, he lined up with 300 other UltraMarathon runners from around the world for The Spartathlon “the daddy, the original UltraMarathon, no race has such history & myth behind it. For many ‘Ultra Runners’ this is it, the ultimate race & the badge of honour”, as Mike puts it. So picture it…7.00 a.m. as the sun rises over The Odeon of Herodes Atticus, under the shadow of the Acropolis in Athens. “It’s a daunting prospect with the odds stacked against you from the start”, said Mike. A look at the race information tells you why. The race covers 153 miles, has an overall time limit of 36 hours, a cut off time of 9hr30mins at Corinth, 50 miles in, 74 checkpoints each with their own individual cut offs, daytime temperatures of around 28-30C, maybe higher, and 4000ft of mountain to cross over at 100 miles. Mike trained for over 9 months and, rattling up 75 to 100 mile runs in the process. Once the race was underway, the City Police performed the remarkable feat of stopping Athens rush hour traffic as the race headed out from Athens to the cheers of the crowd and drivers alike, then to the coast and across to the Peloponnese. -

ΛΙΣΤΑ ΑΝΑΜΟΝΗΣ - WAITING LIST 2019 INTERNATIONAL ATHLETES (Updated 06/07/2019)

ΛΙΣΤΑ ΑΝΑΜΟΝΗΣ - WAITING LIST 2019 INTERNATIONAL ATHLETES (Updated 06/07/2019) Surname Name Sex Country 1 D'ERRICO MICHELE Male Italy 2 SAM JELFS Male United Kingdom 3 HEREJT PETR Male Czech Republic 4 ALBANESE STEFANIA Female Italy 5 ALVAREZ JORGE Male Mexico 6 GRANDI STEFANO Male Italy 7 KALIŠNIK TOMAŽ Male Slovenia 8 UGALDE ASTEINZA JAVIER Male Spain 9 BENNETT JAMES Male United Kingdom 10 HOLVIK SIMEN Male Norway 11 JUHASZ SANDOR Male Hungary 12 FLORES GABRIEL Male United Kingdom 13 LORINDER SUSANN Female Sweden 14 UZIK JAN Male Slovakia 15 KANKAANMAKI MARIANNE Female Finland 16 CAGNANI LUCA Male Italy 17 PAZDEJ PIOTR Male Poland 18 DERIVAZ ERIC Male France 19 KOTAMAKI ELISA Female Finland 20 SWANTON LAURA Female United Kingdom 21 DOYLE NATASHA Female United Kingdom 22 TOIGO GILBERTO Male Brazil 23 ESPINOSA VALDEZ CINTHIA Female Mexico 24 MAREK PAVEL Male Czech Republic 25 BRENK JAN Male Czech Republic 26 ZARAGOZA CAMPILLO MARCO ANTONIO Male Mexico 27 MINGHUA YU Male Chinese Taipei 28 VAN HOORN MARK Male Netherlands 29 SKIRROW JASON Male United Kingdom 30 BĚLAŠKA PŘEMYSL Male Czech Republic 31 SÉLLEY GÁBOR Male Hungary 32 STEWART IAIN Male United Kingdom 33 SUTTON RICHARD Male United Kingdom 34 KOUTSTAAL JONATHAN Male Netherlands 35 BRAEKMAN DAVY Male Belgium 36 MUIR DAVID Male United Kingdom 37 OSMAN-ALLU DOMINIC Male United Kingdom 38 DE OCA CRISTIAN MONTES Male Argentina 39 SUMMERS PETER Male United Kingdom 40 FROLOW JAKUB Male Poland 41 VIKKELSØ LARS RYBERG Male Denmark 42 MÉSZÁROS TAMÁS Male Hungary 43 URSULA HERGER Female Switzerland -

Spartathlon 2015 Race Report When the Masks Come Off

Spartathlon 2015 Race Report When The Masks Come Off By Andrei Nana One of the paintings in our bedroom is an original piece by famous European Artist, Valerian Paraschiv. It is called Masks. The symbolism behind the painting is the truth of everyday life. We all have many masks which we wear in different circumstances. We have one mask for our family, we have one mask for our work, we have one mask for friends, and so on… The explosion of social media sites makes it easy to distinguish and understand an individual’s ability to juggle multiple masks and to balance their use. There is absolutely no one in today’s society who is 100% authentic. We all use those masks with or without ill intent to better function in a group and to just move forward. We use those masks to make ourselves believe that somehow we are more (x) or more (y) depending of what we want to accomplish. Nevertheless, even in a world where truth has so many nuances, there is an absolute truth. Some people call it God, others “the Holy Spirit.” For me that truth is the Spartathlon. It is an ultrarunning race, considered by almost everyone who ran it, the most elite in the world. It involves running from Athens to Sparta, a distance of around 153 miles/246 kilometers in less than 36 hours. It was created based on one of the most pure and selfless actions. An Athenian soldier was sent to Sparta to ask for military help from King Leonidas following a sudden/unexpected attack of the city by the Persian Army. -

The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Endurance and Ultra-Endurance Running

medicina Article The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Endurance and Ultra-Endurance Running Volker Scheer 1,2 , David Valero 1, Elias Villiger 3 , Thomas Rosemann 3 and Beat Knechtle 3,4,* 1 Ultra Sports Science Foundation, 69310 Pierre-Bénite, France; [email protected] (V.S.); [email protected] (D.V.) 2 Health Science Department, Universidad a Distancia de Madrid (UDIMA), Collado Villaba, 28400 Madrid, Spain 3 Institute of Primary Care, University of Zurich, 8091 Zurich, Switzerland; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (T.R.) 4 Medbase St. Gallen Am Vadianplatz, 9006 St. Gallen, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Background and objectives: The COVID-19 outbreak has become a major health and economic crisis. The World Health Organization declared it a pandemic in March 2020, and many sporting events were canceled. Materials and Methods: We examined the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on endurance and ultra-endurance running (UER) and analyzed finishes and events during the COVID-19 pandemic (observation period March 2020–October 2020) to the same time period pre- COVID-19 outbreak (March 2019–October 2019). Results: Endurance finishes decreased during the pandemic (459,029 to 42,656 (male: 277,493 to 25,582; female 181,536 to 17,074; all p < 0.001). Similarly, the numbers of endurance events decreased (213 vs. 61 events; p < 0.001). Average marathon finishing times decreased during the pandemic in men (5:18:03 ± 0:16:34 vs. 4:43:08 ± 0:25:08 h:min:s (p = 0.006)) and women (5:39:32 ± 0:19:29 vs. -

Hellenic Film Society USA Celebrates 200 Years of Greek Independence with Eight Features Inspired by Greek History Through the Ages March 19-28, 2021

Hellenic Film Society USA Celebrates 200 Years of Greek Independence With Eight Features Inspired by Greek History Through the Ages March 19-28, 2021 Astoria, NY — March 15, 2021 —The Hellenic Film Society (HFS) is marking the bicentennial of Greek independence with a special program of eight features. Seven films and an original Netflix episode, all inspired by Greek history, from the Persian Wars to the present, will stream worldwide March 19-28. Each presentation will be accompanied by conversations with filmmakers to provide historical context and insights about the making of the film. To celebrate this milestone in Greek history with its loyal audience, HFS is presenting two features free of charge: Cliffs of Freedom, set during the Greek War of Independence in 1821; and the pilot episode of the hit original Netflix series, Blood of Zeus, based on Greek mythology. Viewers may purchase tickets for the remaining six films individually or buy a pass to all for the special price of $18.21. The eclectic offerings include the work of distinguished Greek-American filmmakers, past and present, from Elia Kazan (America America) to Charley and Vlas Parlapanides (Blood of Zeus creators). Selections range from Hollywood epics to indie documentaries, an original Netflix episode, and two films that focus on the Greek Revolution of 1821. “The Hellenic Film Society is committed to marking this important milestone in Greek history with a film celebration that honors the Greek struggle and the journey of the Greek people since gaining their independence from the Ottoman Turks,” says Jimmy DeMetro, Hellenic Film Society president.