726708602826-Itunes-Booklet.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

2018Patternsonline

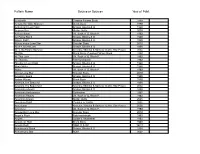

Pattern Name!!!!!Source or Sources!!!!Year of Publ. Acrobatik Creative Pattern Book 1999 Across the Wide Missouri Block Book 1998 Adirondack Log Cabin Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Aegean Sea Stellar Quilts 2009 African Safari Ult. Book of Q. Block P. 1988 Air Force Block Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Album Patch Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Albuquerque Lone Star Singular Stars 2018 Alice's Adventures Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 All in the Family Sampler Knockout Blocks & Sampler Quilts, Star Power 2004 All Star Block Book, Creative Pattern Book 1998 All That Jazz Ult. Book of Q. Block P. 1988 All Thumbs Patchworkbook 1983 Allegheny Log Cabin Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Alma Mater Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Aloha Ult. Book of Q. Block P. 1988 Alpine Lone Star Singular Stars 2018 Amazing Grace Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Amber Waves Block Book 1998 America, the Beautiful Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 America, the Beautiful 2 Knockout Blocks & Sampler Quilts, Star Power 2004 American Abroad Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 American Ambassador Quiltmaker 1982 American Beauty Ult. Book of Q. Block P. 1988 American Dream Stellar Quilts 2005 American Spirit Cookies 'n' Quilts 2001 Americana Knockout Blocks & Sampler Quilts, Star Power 2000 Amethyst Ult. Book of Q. Block P. 1988 Amsterdam Lone Star Singular Stars 2018 Angel's Flight Patchworkbook 1983 Angels Quilter’s Newsletter 1983 Angels on High Block Book 1998 Angels Quilt QNM, Q & OC 1981? Anniversary Block Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Anniversary Star BOM 2002 Pattern Name!!!!!Source or Sources!!!!Year of Publ. Anniversary Stars-45th Anniversary -

EMPOWERING SILENCED VOICES CHOROSYNTHESIS SINGERS Wendy Moy & Jeremiah Selvey, Co-Artistic Directors with Camel Heard & Chorale

CONNECTICUT COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC & DAYTON ARTIST IN RESIDENCE PROGRAM PRESENT EMPOWERING SILENCED VOICES CHOROSYNTHESIS SINGERS Wendy Moy & Jeremiah Selvey, Co-Artistic Directors with Camel Heard & Chorale April 13, 2019, 7:30p.m. Evans Hall DAYTON ARTIST IN RESIDENCE PROGRAM Guests Chorosynthesis Singers, Jeremiah Selvey, & Stephen Lancaster Connecticut College Choirs Wendy Moy, Director of Choral Activities PEACE & HUMAN RIGHTS AUDIENCE SING-ALONG Dona Nobis Pacem (Grant us peace) Wolfgang A. Mozart (1756-1791) When Thunder Comes (2009) Mari Esabel Valverde (b. 1987) CC Camel Heard, CC Chorale, and Chorosynthesis Singers Tristan Filiato, John Frascarelli, and Naveen Gooneratne, percussion Kathleen Bartkowski, piano Wendy Moy, conductor WAR & DEVASTATION A Clear Midnight (2015) Thomas Schuttenhelm (b. 1970) CC Camel Heard and Chorosynthesis Singers Wendy Moy, conductor Come Up from the Fields (1995) C. G. Walden (b. 1955) Diane Walters, Lauren Vanderlinden, and Anthony Ray, soloists Reconciliation (2015) Michael Robert Smith (b. 1989) Chorosynthesis Singers Jeremiah Selvey, conductor 2 Salut Printemps Claude Debussy (1862-1918) CC Camel Heard Ruby Johnson and Sara Van Deusen, soloists Kathleen Bartkowski, piano Wendy Moy, conductor COLONIALISM & BEYOND NORTH AMERICA Evening (2015/2016) Conrad Asman (b. 1996) Chorosynthesis Singers Diane Walters and Anthony Ray, soloists Jeremiah Selvey, conductor Risa Fatal (2015/2016) Tomás Olano (b. 1983) Chorosynthesis Singers Wendy Moy, conductor Blue Phoenix (from Gather These Mirrors) (2009) Kala Pierson (b. 1977) SI, SE PUEDE/YES, WE CAN! Do You Hear How Many You Are? (2010) Keane Southard (b. 1987) CC Camel Heard, CC Chorale, and Chorosynthesis Singers Wendy Moy, conductor INTERMISSION SUICIDE & PULSE CLUB MASS SHOOTING Testimony (2012) Stephen Schwartz (b. -

EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) Chart Ill 1111 Ill Changes #BXNCCVR 3 -DIGIT 908

$6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) Chart Ill 1111 Ill Changes #BXNCCVR 3 -DIGIT 908 II 1111[ III.IIIIIII111I111I11II11I11III I II...11 #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 897 A06 B0098 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A Overview LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 Page 10 New Features l3( AUGUST 2, 2003 Page 57 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT www.billboard.com HOT SPOTS New Player Eyes iTunes BuyMusic.com Rushes Dow nload Service to PC Market BY BRIAN GARRITY Audio -powered stores long offered by Best Buy, Tower Records and fye.com. NEW YORK -An unlikely player has hit the Web What's more, digital music executives say BuyMusic with the first attempt at a Windows -friendly answer highlights a lack of consistency on the part of the labels to Apple's iTunes Music Store: buy.com founder when it comes to wholesaling costs and, more importantly, Scott Blum. content urge rules. The entrepreneur's upstart pay -per-download venture,' In fact, this lack of consensus among labels is shap- buymusic.com, is positioning itself with the advertising ing up as a central challenge for all companies hoping slogan "Music downloads for the rest of us." to develop PC -based download stores. But beyond its iTunes- inspired, big -budget TV mar- "While buy.com's service is the least restrictive [down- the new service is less a Windows load store] that is currently available in the Windows keting campaign, SCOTT BLUI ART VENTURE 5 Trio For A Trio spin on Apple's offering and more like the Liquid (Continued on page 70) Multicultural trio Bacilos garners three nominations for fronts the Latin Grammy Awards. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Blood Meridian Or the Evening Redness in the West Dianne C

European journal of American studies 12-3 | 2017 Special Issue of the European Journal of American Studies: Cormac McCarthy Between Worlds Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12252 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12252 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference European journal of American studies, 12-3 | 2017, “Special Issue of the European Journal of American Studies: Cormac McCarthy Between Worlds” [Online], Online since 27 November 2017, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12252; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas. 12252 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. European Journal of American studies 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: Cormac McCarthy Between Worlds James Dorson, Julius Greve and Markus Wierschem Landscapes as Narrative Commentary in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness in the West Dianne C. Luce The Novel in the Epoch of Social Systems: Or, “Maps of the World in Its Becoming” Mark Seltzer Christ-Haunted: Theology on The Road Christina Bieber Lake On Being Between: Apocalypse, Adaptation, McCarthy Stacey Peebles The Tennis Shoe Army and Leviathan: Relics and Specters of Big Government in The Road Robert Pirro Rugged Resonances: From Music in McCarthy to McCarthian Music Julius Greve and Markus Wierschem Cormac McCarthy and the Genre Turn in Contemporary Literary Fiction James Dorson The Dialectics of Mobility: Capitalism and Apocalypse in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road Simon Schleusener Affect and Gender -

BHM 2008 Spring.Pdf

MAGAZINE COMMITTEE OFFICER IN CHARGE Bill Booher CHAIRMAN Lawrence S Levy VICE CHAIRMEN A Message From the Chairman 1 Tracy L. Ruffeno Gina Steere COPY EDITOR Features Kenneth C. Moursund Jr. EDITORIAL BOARD Katrina’s Gift ................................................. 2 Denise Doyle Samantha Fewox Happy 100th, 4-H .......................................... 4 Katie Lyons Marshall R. Smith III Todd Zucker 2008 RODEOHOUSTONTM ................................. 6 PHOTOGRAPHERS page 2 Debbie Porter The Art of Judging Barbecue .......................... 12 Lisa Van Etta Grand Marshals — Lone Stars ...................... 14 REPORTERS Beverly Acock TM Sonya Aston The RITE Stuff — 10 Years of Success ........ 16 Stephanie Earthman Baird Bill R. Bludworth Rodeo Rookies ............................................... 18 Brandy Divin Teresa Ehrman Show News and Updates Susan D. Emfinger Kate Gunn Charlotte Kocian Corral Club Committees Spotlight ................ 19 Brad Levy Melissa Manning Rodeo Roundup ............................................. 21 Nan McCreary page 4 Crystal Bott McKeon Rochell McNutt Marian Perez Boudousquié Ken Scott Sandra Hollingsworth Smith Kristi Van Aken The Cover Hugo Villarreal RODEOHOUSTON pickup men, Clarissa Webb arguably one of the hardest- HOUSTON LIVESTOCK SHOW working cowboys in the arena, AND RODEO MAGAZINE COORDINATION will saddle up for another year MARKETING & PUBLIC RELATIONS in 2008. DIVISION MANAGING DIRECTOR, page 14 COMMUNICATIONS Clint Saunders Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo™ COORDINATOR, COMMUNICATIONS Kate Bradley DESIGN / LAYOUT CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD: PRESIDENT: CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER: Amy Noorian Paul G. Somerville Skip Wagner Leroy Shafer STAFF PHOTOGRAPHERS VICE PRESIDENTS: Francis M. Martin, D.V. M. C.A. “Bubba” Beasley Danny Boatman Bill Booher Brandon Bridwell Dave Clements Rudy Cano Andrew Dow James C. “Jim” Epps Charlene Floyd Rick Greene Joe Bruce Hancock Darrell N. Hartman Dick Hudgins John Morton John A. -

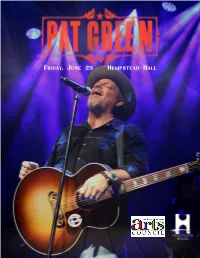

Pat Green Sponsor Brochure PDF to Email

Friday, June 25 Hempstead Hall SOUTH DOWN MAIN 7:00 pm Hempstead Hall Amphitheater A three-time Grammy nominee, Pat Green has become a cultural force across the country that has sold out venues from Nokia Theater in Time Square and House of Blues Los Angeles to the Houston Astrodome in Texas. Respected by his peers, he has co-written with artists ranging from Willie Nelson and Chris Stapleton to Jewel and Rob Thomas. Green’s explosive live shows have made him a fan favorite and a hot ticket landing tours with Willie Nelson, Kenny Chesney, Keith Urban and Dave Matthews Band. Named “the Springsteen of the South West” by People, Green has sold over 2 million records and has released 10 studio albums. He has a string of 15 hits on the Billboard Country Radio Chart and twelve #1 hits on the Texas Radio Chart including his latest single “Drinkin' Days,” which spent an impressive seven weeks at #1. He has been praised by Esquire, NPR, Rolling Stone, People, Billboard, USA Today, American Songwriter, Paste, The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times and has appeared on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, Austin City Limits and Late Show With David Letterman. His album “What I’m For” made its debut at #2 on the Billboard Top Country Albums Chart, which was followed by his critically acclaimed love letter to his fans “Home.” ALL SPONSORSHIPS HELP KEEP Hempstead Hall Amphitheater TICKET PRICES LOW & BENEFIT Friday, June 25, 2021 HEMPSTEAD HALL & SOUTHWEST 6:00 Gates Open | 7:00 South Down Main | 8:00 Pat Green ARKANSAS ARTS COUNCIL. -

Bhm 2007 Spring.Pdf

MAGAZINE COMMITTEE OFFICER IN CHARGE Bill R. Bludworth CHAIRMAN Lawrence S Levy VICE CHAIRMEN A Message From the President 1 Tracy L. Ruffeno Gina Steere COPY EDITOR Features Kenneth C. Moursund Jr. Who We Are: Show Volunteers ...................... 2 EDITORIAL BOARD Denise Doyle Black Heritage Day ........................................ 4 Samantha Fewox Ranching and Wildlife Expo .......................... 7 Katie Lyons Marshall R. Smith III 2007 RODEOHOUSTONTM Entertainers ............ 8 Todd Zucker 2007 Show Schedule ..................................... 12 PHOTOGRAPHERS Debbie Porter RODEOHOUSTON Super Series: Lisa Van Etta It’s a Revolution in Rodeo .......................... 14 page 2 REPORTERS Stampede for Scholarships ............................ 16 Beverly Acock Sonya Aston Stephanie Earthman Baird Committee Spotlights Tish Zumwalt Clark Brandy Divin Souvenir Program .......................................... 18 Teresa Ehrman Susan D. Emfinger Western Art ................................................... 19 Alicia M. Filley Bridget Hennessey Show News and Updates Charlotte Kocian Brad Levy Melissa Manning Third-Year Committee Chairmen Profiles ..... 20 Nan McCreary Rodeo Roundup ............................................. 21 page 14 Terri L. Moran Marian Perez Boudousquié Ken Scott Sandra Hollingsworth Smith Kristi Van Aken Constance White Susan K. Williams The Cover HOUSTON LIVESTOCK SHOW For the Houston Livestock Show AND RODEO and Rodeo’s 75th anniversary MAGAZINE COORDINATION celebration, Hall of Famers MARKETING & PRESENTATIONS George Strait and ZZ Top will DIVISION MANAGING DIRECTOR open and close the festivities. ADVERTISING & PUBLIC RELATIONS Johnnie Westerhaus page 16 MANAGER - INFORMATION / PUBLICATIONS Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo™ Clint Saunders DESIGN / LAYOUT CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD: VICE PRESIDENTS: EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE: LIFETIME MEMBERS - Amy Noorian Paul G. Somerville Louis Bart Joseph T. Ainsworth M.D. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE: STAFF PHOTOGRAPHERS Bill R. Bludworth Jim Bloodworth Don A. Buckalew Francis M. Martin, D.V. -

HENRY and LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL of MUSIC SPRING 2017 Fanfare

HENRY AND LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC SPRING 2017 fanfare 124488.indd 1 4/19/17 5:39 PM first chair A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN One sign of a school’s stature is the recognition received by its students and faculty. By that measure, in recent months the eminence of the Bienen School of Music has been repeatedly reaffirmed. For the first time in the history of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, this spring one of the contestants will be a Northwestern student. EunAe Lee, a doctoral student of James Giles, is one of only 30 pianists chosen from among 290 applicants worldwide for the prestigious competition. The 15th Van Cliburn takes place in May in Ft. Worth, Texas. Also in May, two cello students of Hans Jørgen Jensen will compete in the inaugural Queen Elisabeth Cello Competition in Brussels. Senior Brannon Cho and master’s student Sihao He are among the 70 elite cellists chosen to participate. Xuesha Hu, a master’s piano student of Alan Chow, won first prize in the eighth Bösendorfer and Yamaha USASU Inter national Piano Competition. In addition to receiving a $15,000 cash prize, Hu will perform with the Phoenix Symphony and will be presented in recital in New York City’s Merkin Concert Hall. Jason Rosenholtz-Witt, a doctoral candidate in musicology, was awarded a 2017 Northwestern Presidential Fellowship. Administered by the Graduate School, it is the University’s most prestigious fellowship for graduate students. Daniel Dehaan, a music composition doctoral student, has been named a 2016–17 Field Fellow by the University of Chicago. -

The Annenberg Center Presents the Crossing @ Christmas, December 20, at the Church of the Holy Trinity, Rittenhouse Square

NEWS FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: December 11, 2019 The Annenberg Center Presents The Crossing @ Christmas, December 20, at the Church of the Holy Trinity, Rittenhouse Square “America’s most astonishing choir.” – The New York Times (Philadelphia – December 11, 2019) — The Annenberg Center presents “America’s most astonishing choir” (New York Times), acclaimed Grammy® Award-winning new music choir The Crossing, conducted by Donald Nally, in The Crossing @ Christmas, Friday, December 20, at 7:30 PM, at The Church of the Holy Trinity, Rittenhouse Square, 1904 Walnut Street. Visit AnnenbergCenter.org for ticket information. The program includes David Lang’s Pulitzer-winning the little match girl passion (2008), a work championed by The Crossing and one of the few works they return to repeatedly. Recasting Hans Christian Andersen’s tale in the form of a passion, based loosely on the structure and words of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, David Lang draws a religious and moral equivalency between the suffering of the poor girl and the suffering of Jesus. The Crossing @ Christmas also features the world premiere performance of Spectral Spirits, a major commission from Edie Hill based on poems of Holly Hughes. The new 30-minute work explores the extraordinary beauty and diversity of the natural world found in birds; and it views those birds through a lens of loss and nostalgia. All of the birds in the work, once numbered in millions, are now gone. The Crossing The Crossing is a professional chamber choir conducted by Donald Nally and dedicated to new music. It is committed to working with creative teams to make and record new, substantial works for choir that explore and expand ways of writing for choir, singing in choir and listening to music for choir. -

Spring 2016 Fanfare Rst Chair

spring 2016 fanfare rst chair A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN I the many Bienen School alumni continued with recitals by Stephen Hough and Garrick and iends who have already visited our new home in the Ohlsson (two recent winners of the school’s Jean Gimbel Ryan Center for the Musical Arts, I hope you will have an Lane Prize in Piano Performance), piano professor James opportunity to do so soon. The Giles, and rising star Andrew Tyson; it concludes with Alvin building, a dream of so many Chow, Angela Cheng, and piano professor Alan Chow on for so long, is now a reality that May 15. The school’s Institute for New Music held its second fully lives up to all expectations. conference, NUNC! 2, November 6–8 (see pages 12–13). As with any new facility, Special choral and orchestral concerts spotlighted works by the transition om abstract to previous Nemmers Prize winners and—appropriately meld- concrete has been gradual and ing music with architecture—works written for the consecra- multifaceted. Bienen School tion of iconic buildings. Architecture also took center stage academic music classes began as musicology faculty members Drew Davies, Ryan Dohoney, meeting in the building during and Inna Naroditskaya presented the April 7–8 symposium the 2015 spring quarter, and “Sounding Spaces: A Workshop on Music, Urban Space, faculty and staff moved into their Landscape, and Architecture.” Commissioned works new offices in early summer. On September 2 Northwestern for the school’s yearlong celebration have included new announced that the building would be named in honor of com positions by Joel Puckett, premiered February 5 by Patrick G.