Holy War in Henry Fifth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love Is Come Again Monteverdi Choir Gardiner Love Is Come Again Music for the Springhead Easter Play

Love is come again Monteverdi Choir Gardiner Love is come again Music for the Springhead Easter Play Monteverdi Choir English Baroque Soloists John Eliot Gardiner ‘This personal selection of music for Easter from the 11th to the 20th centuries tells the story of the Resurrection and Christ's appearances to his disciples. It is based on my experience of compiling and directing the music for a mimed Easter play, performed in village churches in Dorset every year between 1963 and 1984, the brainchild of my mother, Marabel Gardiner, to whose memory this recording is dedicated.’ 2 John Eliot Gardiner Marabel Gardiner aged 19 in Florence, 1926; 3 her production notes for the Springhead Easter Play, 1964 The Crucifixion Mary Magdalene at the tomb 1 The Seven Virgins 2:14 7 Eheu! They have taken Jesus 2:55 Trad., Herefordshire Thomas Morley 1557/8-1602 Angharad Rowlands soprano 8 But Mary stood without the sepulchre 3:53 2 O vos omnes 3:52 Heinrich Schütz 1585-1672 Carlo Gesualdo 1566-1613 Historia der Auferstehung Jesu Christi Hugo Hymas Evangelist 3 Woefully array’d 7:44 Gareth Treseder, Ruairi Bowen Jesus William Cornysh 1465-1523 Charlotte Ashley, Angharad Rowlands Alison Ponsford-Hill soprano Mary Magdalene Matthew Venner alto Peter Davoren tenor 9 Bless’d Mary Magdalene 0:57 Christopher Webb bass Trad., English Easter Morning 4 Dum transisset Sabbatum 8:11 John Taverner c.1490-1545 5 Love is come again 2:00 Trad., French 6 Surrexit pastor bonus 5:59 Jean L’Héritier c.1480-1552 4 The Road to Emmaus The Lake Side 10 And behold two of them went that day 2:16 15 Peter saith, I go a-fishing 2:48 Wipo of Burgundy c.995-c.1048 (attrib.) after Jean Tisserand d.1494 Victimae paschali laudes O filii et filiae Hugo Hymas tenor Peter Davoren tenor 11 Abendlied 3:39 16 Kyrie eleison 1:16 Josef Gabriel Rheinberger 1839-1901 Missa Orbis factor 12 Alleluia. -

Holy War in Henry Fifth

Holy War in Henry Fifth Published in Shakespeare Survey 48, Nov./Dec. 1995, reprinted in Shakespearean Criticism Gale Publications, 1996 Steven Marx English Department, Cal Poly University San Luis Obispo [email protected] Joel Altman calls Henry V 'the most active dramatic experience Shakespeare ever offered his audience'.1 The experience climaxes at the end of the final battle with the arrival of news of victory. Here the king orders that two hymns be sung while the dead are buried, the 'Non Nobis' and the 'Te Deum'. In his 1989 film, Kenneth Branagh underlines the theatrical emphasis of this implicit stage direction. He extends the climax for several minutes by setting Patrick Doyle's choral-symphonic rendition of the 'Non Nobis' hymn behind a single tracking shot that follows Henry as he bears the dead body of a boy across the corpse- strewn field of Agincourt. The idea for this operatic device was supplied by Holinshed, who copied it from Halle, who got the story from a chain of traditions that originated in the event staged by the real King Henry in 1415. Henry himself took instruction from another book, the Bible.2 The hymns which Henry requested derive from verses in the psalter. 'Non Nobis' is the Latin title of Psalm 115 , which begins, 'Not unto us, O lord, not unto us, but unto thy Name give the glorie... .' This psalm celebrates the defeat of the Egyptian armies and God's deliverance of Israel at the Red Sea. It comes midway in the liturgical sequence known as The Egyptian Hallelujah extending from Psalm 113-118, a sequence that Jesus and the disciples sang during the Passover celebration at the Last Supper and that Jews still recite at all their great festivals.3 Holinshed refers to the hymn not as 'Non Nobis' but by the title of Psalm 114 , 'In exitu Israel de Aegypto' ('When Israel came out of Egypt').4 The miraculous military victory commemorated in the 'Non Nobis' is the core event of salvation in the Bible, the model of all of God's interventions in human history. -

Translations of the Biblical Passages Are from the King James Bible; Translations of Liturgical Texts Are from the 1549 Anglican Book of Common Prayer

TEXTS AND TRANSLATIONS FOR CHANTS MENTIONED BY DANTE Paul Walker Translations of the Biblical passages are from the King James Bible; translations of liturgical texts are from the 1549 Anglican Book of Common Prayer. IN EXITU ISRAEL 1. In exitu Israel de Aegypto, domus Jacob de populo barbaro: 2. Facta est Judaea sanctificatio ejus: Israel potestas ejus. 3. Mare vidit, et fugit: Jordanis conversus est retrorsum. 4. Montes exsultaverunt ut arietes: et colles sicut agni ovium. 5. Quid est tibi mare quod fugisti? Et tu Jordanis, quia conversus es retrorsum? 6. Montes exsultastis sicut arietes, et colles sicut agni ovium? 7. A facie Domini mota est terra, a facie Dei Jacob: 8. Qui convertit petram in stagna aquarum, et rupem in fontes aquarum. 9. Non nobis Domine, non nobis, sed nomini tuo da gloriam. 10. Super misericordia tua et veritate tua: nequando dicant gentes: Ubi est Deus eorum? 11. Deus autem noster in caelo: omnia quaecumque voluit, fecit. 12. Simulacra gentium argentum et aurum, opera manum hominum. 13. Os habent, et non loquentur: oculos habent, et non videbunt. 14. Aures habent et non audient: nares habent, et non odorabunt. 15. Manus habent et non palpabunt: pedes habent, et non ambulabunt: non clamabunt in gutture suo. 16. Similes illis fiant qui faciunt ea: et omnes qui confidunt in eis. 17. Domus Israel speravit in Domino: adjutor eorum et protector eorum est. 18. Domus Aaron speravit in Domino: adjutor eorum et protector eorum est. 19. Qui timent Dominum speraverunt in Domino: adjutor eorum et protector eorum est. 20. Dominus memor fuit nostri: et benedixit nobis. -

A Manual of Plainsong for Divine Service Containing the Canticles

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com MANUALOF PLAINSONG FOR DIVINE SERVICE CONTAINING THE CANTICLES NOTED THE PSALTER NOTED TO GREGORIAN TONES TOGETHER WITH THE LITANY AND RESPONSES A NEW EDITION PREPARED BY H. B. BRIGGS and W. H. FRERE UNDER THE GENERAL SUPERINTENDENCE OF JOHN STAINER (LATE PRESIDENT OF THE PLAINSONG AND MEDIAEVAL MUSIC SOCIETY) London : NOVELLO AND COMPANY, Limited AND NOVELLO, EWER AND CO., NEW YORK. 1902. rSt\5 LONDON I KOVELLO AND COMPANY, LIMITED PRINTERS. PREFACE. ThE first edition of The Psalter Noted was published in 1849 under the supervision of the late Rev. Thomas Helmore, and secured for the Gregorian Tones a general recognition of their appropriateness for Divine worship. Subsequently Mr. Helmore's scheme was enlarged by the issue of The Canticles Noted, of A Brief Directory, and of three Appendixes to the Psalter; and the whole collection was issued in one volume under the title of A Manual of Plainsong. The Manual had also two companion books, one of Words only containing The Canticles and Psalter Accented, the other a collection of Accompanying Harmonies. Thus complete provision was made for the musical performance of the regular services of the Prayer Book. Practical objections, however, to the monotony of the recitation of several Psalms to one Tone without the relief of Antiphons, added to certain difficulties in the pointing, led to the issue of other Psalters which have competed with The Psalter Noted, but without obtaining, any of them, a marked supremacy ; and nothing has been issued which covers the whole field so completely as Mr. -

St. Luke's Episcopal Church

The Sixth Sunday of Seven Week Advent December 13, 2020 at 10:00 AM St. Luke’s Episcopal Church Spirituality in Action Cover Art: “The Nativity,” c. 1400, Tempera on walnut, 41 x 29.5 cm, in the Galerie mittelalterlicher österreichischer Kunst, Vienna" 2 The Feast of Christ’s Nativity Prelude Non nobis Domine William Byrd (1539 - 1623) Arranged for Brass Trio by S. Lundberg In the Bleak Midwinter Arranged Mark Schweizer (b. 1956) Members of the St. Luke’s Choir In the bleak midwinter frosty wind made moan, Earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone; Snow had fallen, snow on snow, snow on snow, In the bleak midwinter, long ago. Our God, heav'n cannot hold him, nor earth sustain; Heav'n and earth shall flee away, when he comes to reign. In the bleak midwinter a stable place sufficed The Lord God incarnate, Jesus Christ. What can I give him, poor as I am, If I were a shepherd, I would bring a lamb; If I were a wiseman, I would do my part; Yet what I can I give him, give my heart. Call to Worship Deacon Light looked down and saw darkness. People “I will go there,” said light. Deacon Peace looked down and saw war. People “I will go there,” said peace. Deacon Love looked down and saw hatred. People “I will go there,” said love. Deacon So he, the Lord of Light, the Prince of Peace, the King of Love, came down and crept in beside us. Officiant Blessed be God, our strength and our salvation, People now and for ever. -

Second Sunday After Easter TWENTY-SIXTH of APRIL, A.D

OMAHA, NEBRASKA SAINT BARNABAS CHURCH A ROMAN CATHOLIC PARISH OF THE Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter SECOND EVENSONG THIRD SUNDAY OF EASTER, being Second Sunday after Easter TWENTY-SIXTH of APRIL, a.d. 2020 Preces O Lord, open thou our lips. And our mouth shall shew forth thy praise. O God, make speed to save us. O Lord, make haste to help us. Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost. As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be world without end. Amen. Praise ye the Lord The Lord’s name be praised. Psalmody Psalm 114 (113) In éxitu Israël Tonus Peregrinus hen Isrāel |came out of Egypt: W and the house of Jacob from among |the strange people. 2 Judah was |his sanctuary: and Isrāel his |dominion. 3 The |sea |aw that, and fled: Jordan |was driven back. 4 - - - |The mountains skipped like rams : and the little hills |like young sheep. 5 What aileth thee, O thou |sea, that thou fleddest : and thou Jordan, that thou |wast driven back? 6 Ye moun-|tains, that ye skipped like rams : and ye little hills, |like young sheep? 7 Tremble, thou earth, at the |presence of the Lord : at the presence of the God |of Jacob; 8 Who turned the hard rock into |a standing water : and the flint-stone into |a springing well. 9 Glory be to the |Father, and to the Son : and to |the Holy Ghost. 10 As it was in the beginning, is now, |and ever shall be: world without |end. -

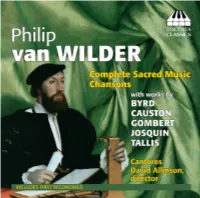

PHILIP VAN WILDER, HENRY VIII's LOST COMPOSER

P PHILIP VAN WILDER, HENRY VIII’s LOST COMPOSER by David Allinson Lutenist, composer and courtier Philip van Wilder may be the most significant ‘lost composer’ of sixteenth-century England. Joseph Kerman called him ‘the most important of several foreign musicians active at the court of Henry VIII of England’,1 yet today his name is known only to specialist musicologists and his music is seldom performed. For anyone interested in Tudor music, van Wilder is a fascinating ‘bridging’ figure who helps to make sense of the dramatic changes in musical style between the reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I: he may well have spurred Tallis to experiment with a freer harmonic and imitative idiom; he shaped the Anglican anthem; he directly inspired Byrd. From around 1520 this ‘lewter’ and ‘mynstrell’ from the Low Countries rose to become, for the best part of three decades, the most prominent and richly rewarded professional musician at the English court. His surviving music testifies to a substantial and original compositional talent. More than that: van Wilder’s motets, chansons and anthems shed vivid light on the development of English music in the decades before, during and after the Reformation. Schooled in the soundworld of Netherlandish (and more specifically, Burgundian) music and fluent in its technicalities, van Wilder was certainly open to conservative English traditions: in Sancte Deus 6]he is found embracing both the spirit and the letter of the pre-Reformation English votive antiphon genre, matching every melisma and false relation of the master, Tallis 5. More significantly in this process of cultural exchange, the cream of London’s composers – relatively isolated from the latest continental fashions – were able to draw directly upon this resident representative of Franco-Flemish practices to transform their own music. -

Shakespeare's Henriadic Monarchy and Chaucerian/Elizabethan Religion

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications -- Department of English English, Department of 2021 Shakespeare's Henriadic Monarchy and Chaucerian/Elizabethan Religion Paul Olson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications -- Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Shakespeare's H enriadic Monarchy and ChaucerianlElizabethan Religion Paul A. Olson Shakespeare, interpreting late medieval English history from the ages of Geoffrey and Thomas Chaucer, gives us a second tetralogy (1595-99) that less defends the "Tudor myth" than creates a lens for viewing the formation of a unitary religious/political culture. Writing near the end of Elizabeth's reign, after serious Catholic insurrection had quieted, he examines how Act of Supremacy sacerdotal monarchy eschew rebellion and decadence, creat ing eidola paralleling Chaucer s Canterbury Tales ones. ill the latter, Chaucer presented, to the court narratives of Catholic clerical failure Jovinian deca dence and th po Ibility of reformed penance. However Sbakespeare tw-ns, for his salvific, from honest penance-Chaucer's solution-to royal contri tion and honest action. The second Henriad debunks old polarities of con formity and non-confomuty by celebrating the monarch's sen e of nationa.l religion and recapitulating unifying themes about celibacy, repentance and rebellion from the age of Chaucer, bringing Elizabethan religious polemics to the stage in a fashion that emulates Chaucer's dramatic court readings in his time and place. -

Architects and Builders Catalog No

PENINSULA BIBLE CHURCH CUPERTINO Architects AND BUILDERS Catalog No. 1598 Genesis 11:1-9 SERIES: OUR STorY OF OriGINS 36th Message Bernard Bell August 7, 2011 In 1415 the English, led by Henry V, defeated a much larger Shem, Ham and Japheth had spread out as nations with their own French army in the Battle of Agincourt. This battle is perhaps most languages (10:5, 20, 31). This story of the Tower of Babel gives us a famous from Shakespeare’s play King Henry V. On the eve of the second perspective on the dispersion of the nations. But there are battle Shakespeare has Henry deliver his famous St Crispin’s Day links between the two sections: Nimrod is the mastermind of the Speech: “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers” (4.3). After the empires of Shinar and Assyria. In the days of Peleg the earth was miraculous victory, Henry says, “Let there be sung Non nobis and Te divided, with Joktan’s line leading to Babel, but Peleg’s line leading Deum” (4.8). Non nobis refers to the opening line of Psalm 115 (Vg around and beyond it. Perhaps we are to read the story of Babel as 113:9) in the Latin Vulgate: Non nobis, Domine, non nobis, sed nomini taking place around the time of Nimrod and Joktan. tuo da gloriam, “Not to us, O Lord, not to us, but to your name give In those days when humanity was unified under one language glory.” Kenneth Branagh’s film (1989) has a beautiful rendition of they moved ever-eastwards. -

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: the Master Musician’S Melodies

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: The Master Musician’s Melodies Bereans Sunday School Placerita Baptist Church 2007 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary A Christmas Meditation on Psalm 115: O LORD, to Your Name Be the Glory! 1.0 Introducing Psalm 115 y After the Battle of Agincourt in France, October 25, 1415, King Henry V commanded his victorious troops to kneel and sing Non nobis, Domine, sed tibi sit gloria (Psalm 115): “This note doth tell me of ten thousand French That in the field lie slain: . Where is the number of our English dead? Edward the Duke of York, the Earl of Suffolk, Sir Richard Ketly, Davy Gam, esquire: None else of name; and of all other men But five and twenty. O God, thy arm was here; And not to us, but to thy arm alone, Ascribe we all! . .” “Let there be sung ‘Non nobis’ and ‘Te Deum’ . .” — William Shakespeare, “The Life of King Henry V,” 4, 8.111-13, 127-28. y Rudyard Kipling, “Non Nobis Domine!” (written for “The Pageant of Parliament” at Royal Albert Hall, London July 1934): NON nobis Domine!— Not unto us, O Lord! The Praise or Glory be Of any deed or word; For in Thy Judgment lies To crown or bring to nought All knowledge or device That man has reached or wrought. y Psalm 115 is the third psalm in the “Egyptian Hallel” (Pss 113–118, see notes on Ps 113), traditionally recited at Passover. 9 Christmas is not Passover, but the Passover could not be fulfilled without Christmas. -

Troy Imagery and Competing Codes of Piety in Shakespeare's

TROY IMAGERY AND COMPETING CODES OF PIETY IN SHAKESPEARE’S EARLY HISTORY PLAYS BY © 2010 Brian J. Harries Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty at the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________ Chairperson Committee members ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Date Defended _____________________ ii The Dissertation Committee for Brian J. Harries certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: TROY IMAGERY AND COMPETING CODES OF PIETY IN SHAKESPEARE’S EARLY HISTORY PLAYS Committee: ________________________ Chairperson ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Date approved: _____________________ iii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION “Is Not the Truth the Truth?”: Shakespeare’s Exploration of the Past……………………1 CHAPTER 1 Pietatem Virumque Cano: Virigilian Ethics and the British Troy Myth on Stage………32 CHAPTER 2 The “Head Whose Churchlike Humors Fits Not for a Crown”:. Henry’s Pius Foils in 1 and 2 Henry VI………………………………………………….86 CHAPTER 3 Emblems and Emptiness: The Decline of Pietas in 3 Henry VI and Richard III………136 CHAPTER 4 “The Mirror of All Christian Kings”: Henry V as a Corrective to the First Tetralogy…………………………………………189 EPILOGUE “All the Argument is a Whore and a Cuckold”: Troy Outside of History in Troilus and Cressida………………………………………224 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………………240 1 Introduction “Is Not the Truth the Truth?”: Shakespeare’s Exploration of the Past “Is not the truth the truth?” Falstaff angrily demands in II.iv of 1 Henry IV when the young Prince Hal challenges his narration of the botched robbery.1 Falstaff has just given his eye-witness account of the band of thieves that set upon him after his own exploits in highway robbery, and he expresses incredulity that anyone would dare question a tale of such iron-clad authority. -

William Byrd's Motets and Canonic Writing in England * Denis Collins

2009 © Denis Collins, Context 33 (2008): 45–65. William Byrd’s Motets and Canonic Writing in England * Denis Collins Scholarship on music of the Elizabethan age has long been concerned with investigating the relationships amongst the great Elizabethan composers Thomas Tallis, William Byrd and Alfonso Ferrabosco the Elder. In particular, the influences on Byrd’s compositional style have been traced not only in his earliest output but also in the mature Latin-texted works.1 While Tallis and other English composers are generally credited with influencing Byrd’s early development, much of Byrd’s mature writing reveals characteristics that can be traced to Ferrabosco. For instance, Joseph Kerman has identified specific points of similarity between the motets of these two composers, while David Wulstan has demonstrated that Byrd’s vocal ranges follow those of Ferrabosco rather than those generally found in English music.2 In * I am grateful to Jessie Ann Owens and Philip Bracanin for comments on earlier versions of this study. A Faculty Fellowship at the University of Queensland Centre for Critical and Cultural Studies from February to June 2006 permitted dedicated work on this project. 1 The classic study of Byrd’s sacred music remains Joseph Kerman, The Masses and Motets of William Byrd [hereafter MMWB] (London: Faber & Faber, 1981). See also Joseph Kerman, ‘Byrd, Tallis, and the Art of Imitation,’ Aspects of Medieval and Renaissance Music: A Birthday Offering to Gustave Reese, ed. Jan LaRue (New York: Norton, 1966) 519–37; reprinted in Joseph Kerman, Write all These Down: Essays on Music (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994) 90–105.