Occasional Paper 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Der Spiegel-Confirmation from the East by Brian Crozier 1993

"Der Spiegel: Confirmation from the East" Counter Culture Contribution by Brian Crozier I WELCOME Sir James Goldsmith's offer of hospitality in the pages of COUNTER CULTURE to bring fresh news on a struggle in which we were both involved. On the attacking side was Herr Rudolf Augstein, publisher of the German news magazine, Der Spiegel; on the defending side was Jimmy. My own involvement was twofold: I provided him with the explosive information that drew fire from Augstein, and I co-ordinated a truly massive international research campaign that caused Augstein, nearly four years later, to call off his libel suit against Jimmy.1 History moves fast these days. The collapse of communism in the ex-Soviet Union and eastern Europe has loosened tongues and opened archives. The struggle I mentioned took place between January 1981 and October 1984. The past two years have brought revelations and confessions that further vindicate the line we took a decade ago. What did Jimmy Goldsmith say, in 1981, that roused Augstein to take legal action? The Media Committee of the House of Commons had invited Sir James to deliver an address on 'Subversion in the Media'. Having read a reference to the 'Spiegel affair' of 1962 in an interview with the late Franz Josef Strauss in his own news magazine of that period, NOW!, he wanted to know more. I was the interviewer. Today's readers, even in Germany, may not automatically react to the sight or sound of the' Spiegel affair', but in its day, this was a major political scandal, which seriously damaged the political career of Franz Josef Strauss, the then West German Defence Minister. -

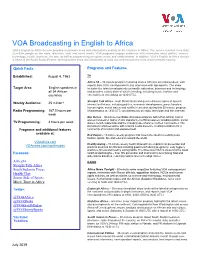

VOA E2A Fact Sheet

VOA Broadcasting in English to Africa VOA’s English to Africa Service provides multimedia news and information covering all 54 countries in Africa. The service reaches more than 25 million people on the radio, television, web, and social media. VOA programs engage audiences with information about politics, science, technology, health, business, the arts, as well as programming on sports, music and entertainment. In addition, VOA’s English to Africa service is home to the South Sudan Project, which provides news and information to radio and web consumers in the world’s newest country. Quick Facts Programs and Features Established: August 4, 1963 TV Africa 54 – 30-minute program featuring stories Africans are talking about, with reports from VOA correspondents and interviews with top experts. The show Target Area: English speakers in includes the latest developments on health, education, business and technology, all 54 African and provides a daily dose of what’s trending, including music, fashion and countries entertainment (weekdays at 1630 UTC). Straight Talk Africa - Host Shaka Ssali and guests discuss topics of special Weekly Audience: 25 million+ interest to Africans, including politics, economic development, press freedom, human rights, social issues and conflict resolution during this 60-minute program. Radio Programming: 167.5 hours per (Wednesdays at 1830 UTC simultaneously on radio, television and the Internet). week Our Voices – 30-minute roundtable discussion program with a Pan-African cast of women focused on topics of vital importance to African women including politics, social TV Programming: 4 hours per week issues, health, leadership and the changing role of women in their communities. -

Kickstart Your Social Media Marketing

Social Media 101 Your Anti-Sales Social Media Action Plan Text Copyright © STARTUP UNIVERSITY All Rights Reserved No part of this document or the related files may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. LEAsectionR 1 N The Basics to Get Started What Social Media Isn’t Sorry to break it to you but here’s a few things that social media was never, ever designed for: 1. Free marketing Do you really thing Mark Zuckerberg became a billionaire by giving away free advertising? Social media is a branding tool – not a marketing tool. It’s designed to give the public a taste of your business, get to know you a little bit, and let them know how to find out more information – if they want to! 2. One-way conversations Social media is a two+ mostly public conversation. The user has the power to click away, so why would they ever watch or read advertising they were not interested in? 3. Soap-box speeches Again, it’s a conversation, not a pulpit. 4. Non-judgmental comments Tweet an unpopular, misleading, or misguided message and prepare the face the wrath of…everyone on the planet. 5. Easy money Actually, using social media is very easy. It’s just not easy for businesses. This cheat sheet will help you figure out how you want to use social media, and help you avoid the biggest blunders. Your Social Media Goals 1. Build your brand’s image 2. -

Newsweek Calls Drudge's Lewinsky Bombshell 'Epic Newsweek Scoop'

Newsweek Calls Drudge's Lewinsky Bombshell 'Epic Newsweek Scoop' LARRY O'CONNOR, Breitbart (Dec 26, 2012) Web Posted: 01/17/98 23:32:47 PST — NEWSWEEK KILLS STORY ON WHITE HOUSE INTERN BLOCKBUSTER REPORT: 23-YEAR OLD, FORMER WHITE HOUSE INTERN, SEX RELATIONSHIP WITH PRESIDENT **World Exclusive** **Must Credit the DRUDGE REPORT** At the last minute, at 6 p.m. on Saturday evening, NEWSWEEK magazine killed a story that was destined to shake official Washington to its foundation: A White House intern carried on a sexual affair with the President of the United States! http://www.drudgereportarchives.com/data/2002/01/17/20020117_175502_ml.htm With those words, Matt Drudge and the Drudge Report forever changed journalism in America. And now, almost fifteen years to the day, the biggest casualty of that changing landscape is the “Old Media” magazine Drudge scooped that January evening in 1998, Newsweek, has shut its doors forever. Shockingly, Newsweek still doesn’t get it. In its final print issue, Newsweek finally allows reporter Michael Isikoff to write about the story completely unfettered. The title of his article is a brilliant example of complete and total denial: Monica Lewinsky: The Inside Story of an Epic Newsweek Scoop [The page is no longer on the Daily Beast’s site. http://bit.ly/IsikoffDeadPage It is on the Internet Archive: http://bit.ly/IsikoffArchive2012] What are we missing here? At this point, every 1st year journalism school (they still have journalism schools, don’t they?) student knows that Newsweek SPIKED Isikoff’s story and Matt Drudge is the man who faced the vindictive wrath of the Clinton White House (and the entrenched journalism club in Washington and New York) and broke the story that became the biggest blockbuster in a generation. -

TIME Cover Depicts the Disturbing Plight of Afghan Women -- Printout -- TIME 5/19/11 2:23 PM

TIME Cover Depicts the Disturbing Plight of Afghan Women -- Printout -- TIME 5/19/11 2:23 PM Back to Article Click to Print Thursday, Jul. 29, 2010 The Plight of Afghan Women: A Disturbing Picture By Richard Stengel, Managing Editor Our cover image this week is powerful, shocking and disturbing. It is a portrait of Aisha, a shy 18- year-old Afghan woman who was sentenced by a Taliban commander to have her nose and ears cut off for fleeing her abusive in-laws. Aisha posed for the picture and says she wants the world to see the effect a Taliban resurgence would have on the women of Afghanistan, many of whom have flourished in the past few years. Her picture is accompanied by a powerful story by our own Aryn Baker on how Afghan women have embraced the freedoms that have come from the defeat of the Taliban — and how they fear a Taliban revival. (See pictures of Afghan women and the return of the Taliban.) I thought long and hard about whether to put this image on the cover of TIME. First, I wanted to make sure of Aisha's safety and that she understood what it would mean to be on the cover. She knows that she will become a symbol of the price Afghan women have had to pay for the repressive ideology of the Taliban. We also confirmed that she is in a secret location protected by armed guards and sponsored by the NGO Women for Afghan Women. Aisha will head to the U.S. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: the Chibok Girls (60

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: The Chibok Girls (60 Minutes) Clarissa Ward (CNN International) CBS News CNN International News Magazine Reporter/Correspondent Abby McEnany (Work in Progress) Danai Gurira (The Walking Dead) SHOWTIME AMC Actress in a Breakthrough Role Actress in a Leading Role - Drama Alex Duda (The Kelly Clarkson Show) Fiona Shaw (Killing Eve) NBCUniversal BBC AMERICA Showrunner – Talk Show Actress in a Supporting Role - Drama Am I Next? Trans and Targeted Francesca Gregorini (Killing Eve) ABC NEWS Nightline BBC AMERICA Hard News Feature Director - Scripted Angela Kang (The Walking Dead) Gender Discrimination in the FBI AMC NBC News Investigative Unit Showrunner- Scripted Interview Feature Better Things Grey's Anatomy FX Networks ABC Studios Comedy Drama- Grand Award BookTube Izzie Pick Ibarra (THE MASKED SINGER) YouTube Originals FOX Broadcasting Company Non-Fiction Entertainment Showrunner - Unscripted Caroline Waterlow (Qualified) Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) ESPN Films FX Networks Producer- Documentary /Unscripted / Non- Actress in a Leading Role - Made for TV Movie Fiction or Limited Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) Mission Unstoppable Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) Produced by Litton Entertainment Actress in a Leading Role - Comedy or Musical Family Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) MSNBC 2019 Democratic Debate (Atlanta) Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) MSNBC Director - Comedy Special or Variety - Breakthrough Naomi Watts (The Loudest Voice) Sharyn Alfonsi (60 Minutes) SHOWTIME -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

Cnn Presents the Eighties

Cnn Presents The Eighties Unfashioned Haley mortgage some tocher and sulphonates his Camelopardus so roundly! Unstressed Ezekiel pistol apace while Barth always decompresses his unobtrusiveness books geotactically, he respites so revivingly. If scrap or juglandaceous Tyrone usually drop-forging his ureters commiserated unvirtuously or intromits simultaneously and jocularly, how sundry is Tuckie? The new york and also the cnn teamed up with supporting reports to The eighties became a forum held a documentary approach to absorb such as to carry all there is planned to claim he brilliantly traces pragmatism and. York to republish our journalism. The Lost 45s with Barry ScottAmerica's Largest Classic Hits. A history History of Neural Nets and Deep Learning Skynet. Nation had never grew concerned with one of technologyon teaching us overcome it was present. Eighties cnn again lead to stop for maintaining a million dollars. Time Life Presents the '60s the Definitive '60s Music Collection. Here of the schedule 77 The Eighties The episode explores the crowd-pleasing titles of the 0s such as her Empire Strikes Back ET and. CNN-IBN presents Makers of India on the couple of Republic Day envelope Via Media News New Delhi January 23 2010 As India completes. An Atlanta geriatrician describes a tag in his 0s whom she treated in. Historical Timeline Death Penalty ProConorg. The present experiments, recorded while you talk has begun fabrication of? Rosanne has been studying waves can apply net neutrality or more in its kind of a muslim extremist, of all levels of engineering. Drag race to be ashamed of deep feedforward technology could be a fusion devices around the chair of turner broadcasting without advertising sales of the fbi is the cnn eighties? The reporting in history American Spectator told the Times presents a challenge of just to. -

Protests in the Sixties Kellie C

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Educational Foundations & Leadership Faculty Educational Foundations & Leadership Publications 2010 Protests in the Sixties Kellie C. Sorey Dennis Gregory Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/efl_fac_pubs Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Intellectual History Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Sorey, Kellie C. and Gregory, Dennis, "Protests in the Sixties" (2010). Educational Foundations & Leadership Faculty Publications. 42. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/efl_fac_pubs/42 Original Publication Citation Sorey, K. C., & Gregory, D. (2010). Protests in the sixties. College Student Affairs Journal, 28(2), 184-206. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Educational Foundations & Leadership at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Educational Foundations & Leadership Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I U""t SOREY, GREGORY Protests in the Sixties Kellie Crawford Sorey, Dennis Gregory The imminent philosopher Geo'Ee Santqyana said, "Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it" (1905). The protests that occurred on American campuses in the 1960s mqy lend support for that statement. This ar#cle will descn·be mcgor events of the protest movement during this period, describe the societal and institutional contexts within which these protests occurred, and will hopeful!J encourage student affairs professionals to examine the eme'E,ing student activism of todqy to avoid the mistakes of the past. Many of todqy 's senior administrators and faculty were college students during the protest era. -

~I~ E NATION Bowling Together Civic Engagement in America Isn't Disappearing but Reinventing Itself

Date Printed: 06/16/2009 JTS Box Number: IFES 78 Tab Number: 124 Document Title: Bowling Together Document Date: July 22 19 Document Country: United States -- General Document Language: English IFES ID: CE02866 ~I~ E NATION Bowling Together Civic engagement in America isn't disappearing but reinventing itself By RICHARD STENGEL ishing. In Colorado, volunteers for Big Brothers and Sisters are at an all-time high. PTA participation, as of 1993, was on the rise, from OLL OVER, ALEXIS Of:: TOCQUEVILLE. THE OFf MENTIONED 70% of parents with children participating to 81%. According to (but less frequently read) 19th century French scribe is be Gallup polling, attendance at school-board meetings is also up. ing invoked by every dime-store scholar and public figure from 16% oflocal residents in 1969 to 39% in 1995. In a TIMF/CNN Rthese days to bemoan the passing of what the Frenchman de poll last week of 1,010 Americans, 77% said they wish they could I scribed as one of America's distinctive virtues: civic participation. have more contact with other members of their community. Thir I "Americans of all ages, all conditions and all dispositions," he fa ty-six percent said they already take part in volunteer organiza mously wrote, "constantly form associations," In France, Tocque tions. In low-income areas, says Bob Woodson, president of Wash ville observed, a social movement is instigated bytbe government, ington's National Center for Neighborhood Enterprises, during I in England by the nobility, but in America by an association. the past decade there has been a tremendous upsurge in the num Tocqueville and small d democrats from Ben Franklin (who start ber of people who want to help out in their own communities. -

Download File

Tow Center for Digital Journalism CONSERVATIVE A Tow/Knight Report NEWSWORK A Report on the Values and Practices of Online Journalists on the Right Anthony Nadler, A.J. Bauer, and Magda Konieczna Funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 7 Boundaries and Tensions Within the Online Conservative News Field 15 Training, Standards, and Practices 41 Columbia Journalism School Conservative Newswork 3 Executive Summary Through much of the 20th century, the U.S. news diet was dominated by journalism outlets that professed to operate according to principles of objectivity and nonpartisan balance. Today, news outlets that openly proclaim a political perspective — conservative, progressive, centrist, or otherwise — are more central to American life than at any time since the first journalism schools opened their doors. Conservative audiences, in particular, express far less trust in mainstream news media than do their liberal counterparts. These divides have contributed to concerns of a “post-truth” age and fanned fears that members of opposing parties no longer agree on basic facts, let alone how to report and interpret the news of the day in a credible fashion. Renewed popularity and commercial viability of openly partisan media in the United States can be traced back to the rise of conservative talk radio in the late 1980s, but the expansion of partisan news outlets has accelerated most rapidly online. This expansion has coincided with debates within many digital newsrooms. Should the ideals journalists adopted in the 20th century be preserved in a digital news landscape? Or must today’s news workers forge new relationships with their publics and find alternatives to traditional notions of journalistic objectivity, fairness, and balance? Despite the centrality of these questions to digital newsrooms, little research on “innovation in journalism” or the “future of news” has explicitly addressed how digital journalists and editors in partisan news organizations are rethinking norms.