Identity Management, Privacy, and Price Discrimination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dod Enterpriseidentity, Credential, and Access Management (ICAM)

UNCLASSIFIED DoD Enterprise Identity, Credential, and Access Management (ICAM) Reference Design Version 1.0 June 2020 Prepared by Department of Defense, Office of the Chief Information Officer (DoD CIO) DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT C. Distribution authorized to U.S. Government agencies and their contractors (Administrative or Operational Use). Other requests for this document shall be referred to the DCIO-CS. UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Document Approvals Prepared By: N. Thomas Lam IE/Architecture and Engineering Department of Defense, Office of the Chief Information Officer (DoD CIO) Thomas J Clancy, COL US Army CS/Architecture and Capability Oversight, DoD ICAM Lead Department of Defense, Office of the Chief Information Officer (DoD CIO) Approved By: Peter T. Ranks Deputy Chief Information Officer for Information Enterprise (DCIO IE) Department of Defense, Office of the Chief Information Officer (DoD CIO) John (Jack) W. Wilmer III Deputy Chief Information Officer for Cyber Security (DCIO CS) Department of Defense, Office of the Chief Information Officer (DoD CIO) ii UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Version History Version Date Approved By Summary of Changes 1.0 TBD TBD Renames and replaces the IdAM Portfolio Description dated August 2015 and the IdAM Reference Architecture dated April 2014. (Existing IdAM SDs and TADs will remain valid until updated versions are established.) Updates name from Identity and Access Management (IdAM) to Identity, Credential, and Access Management (ICAM) to align with Federal government terminology Removes and cancels -

Mastering Identity and Access Management

Whitepaper Mastering Identity and Access Management Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Types of users ............................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Types of identities ..................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Local identities .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Network identities .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Cloud identities ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 IAM concepts ............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 IAM system overview ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 IAM system options -

Identity Management

Identity Management A White Paper by: Skip Slone & The Open Group Identity Management Work Area A Joint Work Area of the Directory Interoperability Forum, Messaging Forum, Mobile Management Forum, and Security Forum March, 2004 Copyright © 2004 The Open Group All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. The materials contained in Appendix B of this document is: Copyright © 2003 Securities Industry Middleware Council, Inc. (SIMC). All rights reserved. The Open Group has been granted permission to reproduce the materials in accordance with the publishing guidelines set out by SIMC. The materials have previously been published on the SIMC web site (www.simc-inc.org). Boundaryless Information Flow is a trademark and UNIX and The Open Group are registered trademarks of The Open Group in the United States and other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Identity Management Document No.: W041 Published by The Open Group, March, 2004 Any comments relating to the material contained in this document may be submitted to: The Open Group 44 Montgomery St. #960 San Francisco, CA 94104 or by Electronic Mail to: [email protected] www.opengroup.org A White Paper Published by The Open Group 2 Contents Executive Summary 4 Introduction 5 Key Concepts 6 Business Value of Identity Management 17 Identity Management -

Ts 124 482 V14.0.0 (2017-04)

ETSI TS 124 482 V14.0.0 (2017-04) TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION LTE; Mission Critical Services (MCS) identity management; Protocol specification (3GPP TS 24.482 version 14.0.0 Release 14) 3GPP TS 24.482 version 14.0.0 Release 14 1 ETSI TS 124 482 V14.0.0 (2017-04) Reference RTS/TSGC-0124482ve00 Keywords LTE ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice The present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org/standards-search The present document may be made available in electronic versions and/or in print. The content of any electronic and/or print versions of the present document shall not be modified without the prior written authorization of ETSI. In case of any existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions and/or in print, the only prevailing document is the print of the Portable Document Format (PDF) version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at https://portal.etsi.org/TB/ETSIDeliverableStatus.aspx If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: https://portal.etsi.org/People/CommiteeSupportStaff.aspx Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and microfilm except as authorized by written permission of ETSI. -

Securing Digital Identities in the Cloud by Selecting an Apposite Federated Identity Management from SAML, Oauth and Openid Connect

Securing Digital Identities in the Cloud by Selecting an Apposite Federated Identity Management from SAML, OAuth and OpenID Connect Nitin Naik and Paul Jenkins Defence School of Communications and Information Systems Ministry of Defence, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] and [email protected] Abstract—Access to computer systems and the information this sensitive data over insecure channels poses a significant held on them, be it commercially or personally sensitive, is security and privacy risk. This risk can be mitigated by using naturally, strictly controlled by both legal and technical security the Federated Identity Management (FIdM) standard adopted measures. One such method is digital identity, which is used to authenticate and authorize users to provide access to IT in the cloud environment. Federated identity links and employs infrastructure to perform official, financial or sensitive operations users’ digital identities across several identity management within organisations. However, transmitting and sharing this systems [1], [2]. FIdM defines a unified set of policies and sensitive information with other organisations over insecure procedures allowing identity management information to be channels always poses a significant security and privacy risk. An transportable from one security domain to another [3], [4]. example of an effective solution to this problem is the Federated Identity Management (FIdM) standard adopted in the cloud Thus, a user accessing data/resources on one secure system environment. The FIdM standard is used to authenticate and could then access data/resources from another secure system authorize users across multiple organisations to obtain access without both systems needing individual identities for the to their networks and resources without transmitting sensitive single user. -

Integrator's Guide / Forgerock Identity Management 6.0

Integrator's Guide / ForgeRock Identity Management 6.0 Latest update: 6.0.0.6 Anders Askåsen Paul Bryan Mark Craig Andi Egloff Laszlo Hordos Matthias Tristl Lana Frost Mike Jang Daly Chikhaoui Nabil Maynard ForgeRock AS 201 Mission St., Suite 2900 San Francisco, CA 94105, USA +1 415-599-1100 (US) www.forgerock.com Copyright © 2011-2017 ForgeRock AS. Abstract Guide to configuring and integrating ForgeRock® Identity Management software into identity management solutions. This software offers flexible services for automating management of the identity life cycle. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. ForgeRock® and ForgeRock Identity Platform™ are trademarks of ForgeRock Inc. or its subsidiaries in the U.S. and in other countries. Trademarks are the property of their respective owners. UNLESS OTHERWISE MUTUALLY AGREED BY THE PARTIES IN WRITING, LICENSOR OFFERS THE WORK AS-IS AND MAKES NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND CONCERNING THE WORK, EXPRESS, IMPLIED, STATUTORY OR OTHERWISE, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, WARRANTIES OF TITLE, MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, NONINFRINGEMENT, OR THE ABSENCE OF LATENT OR OTHER DEFECTS, ACCURACY, OR THE PRESENCE OF ABSENCE OF ERRORS, WHETHER OR NOT DISCOVERABLE. SOME JURISDICTIONS DO NOT ALLOW THE EXCLUSION OF IMPLIED WARRANTIES, SO SUCH EXCLUSION MAY NOT APPLY TO YOU. EXCEPT TO THE EXTENT REQUIRED BY APPLICABLE LAW, IN NO EVENT WILL LICENSOR BE LIABLE TO YOU ON ANY LEGAL THEORY FOR ANY SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR EXEMPLARY DAMAGES ARISING OUT OF THIS LICENSE OR THE USE OF THE WORK, EVEN IF LICENSOR HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. -

Oracle Data Sheet

ORACLE DATA SHEET ORACLE IDENTITY MANAGER 11g KEY FEATURES Oracle Identity Manager is a highly flexible and scalable • Self-service identity management enterprise identity administration system that provides operational drives user productivity, increases user and business efficiency by providing centralized administration & satisfaction and optimizes IT efficiency • Universal delegated administration complete automation of identity and user provisioning events enhances security and reduces costs across enterprise as well as extranet applications. It manages the • Requests with approval workflows and entire identity and role lifecycle to meet changing business and policy-driven provisioning improves IT efficiency, enhances security and regulatory requirements and provides essential reporting and enables compliance compliance functionalities. By applying the business rules, roles, • Password management reduces IT and audit policies, it ensures consistent enforcement of identity help desk costs, and improves service based controls and reduces ongoing operational and compliance levels • Integration solutions featuring Adapter costs. Factory and pre-configured connectors enables quick and low cost system integration Introduction Oracle Identity Manager is a highly flexible and scalable enterprise identity management KEY BENEFITS system that is designed to administer user access privileges across a company's resources • Increased security: Enforce internal throughout the entire identity management life cycle, from initial on-boarding to final -

SAP Identity Management Password Hook Configuration Guide Company

CONFIGURATION GUIDE | PUBLIC Document Version: 1.0 – 2019-11-25 SAP Identity Management Password Hook Configuration Guide company. All rights reserved. All rights company. affiliate THE BEST RUN 2019 SAP SE or an SAP SE or an SAP SAP 2019 © Content 1 SAP Identity Management Password Hook Configuration Guide.........................3 2 Overview.................................................................. 4 3 Security and Policy Issues.....................................................5 4 Files and File Locations .......................................................6 5 Installing and Upgrading Password Hook..........................................8 5.1 Installing Password Hook....................................................... 8 5.2 Upgrading Password Hook...................................................... 9 6 Configuring Password Hook....................................................11 7 Integrating with the Identity Center.............................................18 8 Implementation Considerations................................................21 9 Troubleshooting............................................................22 SAP Identity Management Password Hook Configuration Guide 2 PUBLIC Content 1 SAP Identity Management Password Hook Configuration Guide The purpose of the SAP Identity Management Password Hook is to synchronize passwords from a Microsoft domain to one or more applications. This is achieved by capturing password changes from the Microsoft domain and updating the password in the other applications -

Becoming a Cybersecurity Expert a Career Guide for Professionals and Students

Becoming a Cybersecurity Expert A career guide for professionals and students Introduction Cybersecurity is a new name for the computer and network security profession in a world where everything is increasingly connected to everything to communicate and exchange data. As we further discuss below, the cybersecurity risk landscape is changing as more consumers and businesses are shopping and communicating online, storing and processing data in the cloud, and, embracing portable, smart, and Internet connected devices to automate tasks and improve lives. Cybersecurity has become a hot topic for two main reasons. First, increased hacking cases often result in compromised business information including personal information of customers which must be protected under various privacy and security laws. And second, there is a serious shortage of cybersecurity talent according to many research studies and various countries are scrambling to find the best way to develop cybersecurity experts. In fact, because of the global shortage of cybersecurity experts, some countries such as Australia have expressed a desire to become the leader in cybersecurity talent export to other countries as a way to generate revenue. The cybersecurity talent shortages are expected to affect many countries and last for many years which is why this guide is written to discuss the risk, encourage professionals in related fields and students to pursue a career in cybersecurity, and, seek the support of businesses and governments to promote the profession. About this Guide This guide was produced by Identity Management Institute to provide career information and answer common questions for becoming a cybersecurity expert. This eBook intends to provide a short yet comprehensive guide to encourage and educate others for becoming a cybersecurity expert. -

Managing Identity and Authentication on the Internet an Introduction

Managing Identity and Authentication on the Internet An Introduction Identity on the Internet is fluid and uncertain. Online identities are provided by networks that are loosely coupled to each other and to the official identities provided by governments. Certainty or authenticity comes from personal acquaintance, contract or trust in a network administrator. These solutions are not scaleable and will not lead to the trusted public networks needed to take full advantage of digital technologies. In response , governments and commercial providers are creating systems to manage and authenticate online identities. Governments in the U.S. and elsewhere may make robust digital identities a requirement for citizens to receive services and benefits online. Commercia l services will use authentication of identities to authorize services and transactions as autonomous software agents, ubiquitous computer networks and wireless connectivity further extend the reach of the Internet into business and consumer activities. Interaction between these government -issued identities and commercial services is unavoidable. While individuals will use a range of identities online (from near -anonymous to legally binding), high -value or high -risk transactions and services will require r obust identities issued by or equivalent to those provided by governments. The result is interconnected policy problems involving the interoperability and robustness of digital identities. Neither problem is technical. They ask how an identity issued in o ne autonomous system can authorize actions in another, and how much trust one system can place in an identity issued by another. As consumers and firms assume (or are assigned) online identities provided by both the public and private sectors, governments, companies and citizens will need to decide how autonomous and heterogeneous systems cooperate and interoperate in managing Internet identities. -

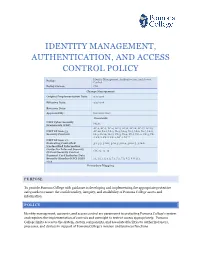

Identity Management, Authentication, and Access Control Policy

IDENTITY MANAGEMENT, AUTHENTICATION, AND ACCESS CONTROL POLICY Identity Management, Authentication, and Access Policy: Control Policy Owner: CIO Change Management Original Implementation Date: 3/7/2018 Effective Date: 3/7/2018 Revision Date: Approved By: Executive Staff Crosswalk NIST Cyber Security PR.AC Framework (CSF) AC-2, AC-3, AC-4, AC-5, AC-6, AC-16, AC-17, AC-19, NIST SP 800-53 AC-20, IA-1, IA-2, IA-3, IA-4, IA-5, IA-6, IA-7, IA-8, Security Controls IA-9, IA-10, IA-11, PS-3, PS-4, PS-5, PE -2, PE-3, PE- 4, PE-5, PE-6, PE-9, SC-4, SC-7 NIST SP 800-171 Protecting Controlled 3.1, 3.5, 3.10.1, 3.10.3, 3.10.4, 30.10.5, 3.10.6 Unclassified Information Center for Internet Security CSC 12, 15, 16 Critical Security Control Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 4.3, 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 8.7, 8.8, 11.1, v3.2 Procedure Mapping PURPOSE To provide Pomona College with guidance in developing and implementing the appropriate protective safeguards to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of Pomona College assets and information. POLICY Identity management, accounts, and access control are paramount to protecting Pomona College’s system and requires the implementation of controls and oversight to restrict access appropriately. Pomona College limits access to the system, system components, and associated facilities to authorized users, processes, and devices in support of Pomona College’s mission and business functions. -

Identity Management Systems and Secured Access Control Anat Hovav Korea University Business School, [email protected]

Communications of the Association for Information Systems Volume 25 | Number 1 Article 42 12-1-2009 Tutorial: Identity Management Systems and Secured Access Control Anat Hovav Korea University Business School, [email protected] Ron Berger Seoul National University Recommended Citation Hovav, Anat and Berger, Ron (2009) "Tutorial: Identity Management Systems and Secured Access Control," Communications of the Association for Information Systems: Vol. 25, Article 42. Available at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/cais/vol25/iss1/42 This material is brought to you by the Journals at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for inclusion in Communications of the Association for Information Systems by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tutorial: Identity Management Systems and Secured Access Control Anat Hovav Korea University Business School [email protected] Ron Berger Seoul National University Identity Management has been a serious problem since the establishment of the Internet. Yet little progress has been made toward an acceptable solution. Early Identity Management Systems (IdMS) were designed to control access to resources and match capabilities with people in well-defined situations, Today’s computing environment involves a variety of user and machine centric forms of digital identities and fuzzy organizational boundaries. With the advent of inter-organizational systems, social networks, e-commerce, m-commerce, service oriented computing, and automated agents, the characteristics of IdMS face a large number of technical and social challenges. The first part of the tutorial describes the history and conceptualization of IdMS, current trends and proposed paradigms, identity lifecycle, implementation challenges and social issues.