Downloaded for Personal Non-Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGENDA ITEM NO.-.-.-.- A02 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL

AGENDA ITEM NO.-.-.-.- a02 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL REPORT To: COMMUNITY SERVICES COMMITTEE Subject: COMMUNITY GRANTS SCHEME GRANTS TO PLAYSCHEMES - SUMMER 2001 JMcG/ Date: 12 SEPTEMBER 2001 Ref: BP/MF 1. PURPOSE 1.1 At its meeting of 15 May 2001 the community services (community development) sub committee agreed to fund playschemes operating during the summer period and in doing so agreed to apply the funding formula adopted in earlier years. The committee requested that details of the awards be reported to a future meeting. Accordingly these are set out in the appendix. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 It is recommended that the committee: (i) note the contents of the appendix detailing grant awards to playschemes which operated during the summer 2001 holiday period. Community Grants Scheme - Playschemes 2001/2002 Playschemes Operating during Summer 2001 Loma McMeekin PSOl/O2 - 001 Bellshill Out of School Service Bellshill & surrounding area 10 70 f588.00 YMCA Orbiston Centre YMCA Orbiston Centre Liberty Road Liberty Road Bellshill Bellshill MU 2EU MM 2EU ~~ PS01/02 - 003 Cambusnethan Churches Holiday Club Irene Anderson Belhaven, Stewarton, 170 567.20 Cambusnethan North Church 45 Ryde Road Cambusnethan, Coltness, Kirk Road Wishaw Newmains Cambusnethan ML2 7DX Cambusnethan Old & Morningside Parish Church Greenhead Road Cambusnethan Mr. Mohammad Saleem PSO 1/02 - 004 Ethnic Junior Group North Lanarkshire 200 6 f77.28 Taylor High School 1 Cotton Vale Carfin Street Dalziel Park New Stevenston Motherwell. MLl 5NL PSO1102-006 Flowerhill Parish Church/Holiday -

Woodhead Farm Blackwood Estate • Lesmahagow • Lanark

WOODHEAD FARM BLACKWOOD ESTATE • LESMAHAGOW • LANARK SPACIOUS EARLY VICTORIAN FARMHOUSE WITH FLEXIBLE LAYOUT AND 2 ACRES OF GARDEN. WOODHEAD FARM BLACKWOOD ESTATE • LESMAHAGOW LANARK • ML11 0JG ENTRANCE HALL DRAWING ROOM / LIVING ROOM SITTING ROOM DINING ROOM CONSERVATORY 2 KITCHENS UTILITY ROOM OFFICE STUDIO BEDROOM WITH EN SUITE 3 FURTHER BEDROOMS FAMILY BATHROOM 2 SHOWER ROOMS LOFT ROOM / BEDROOM FLOORED ATTIC DOUBLE GARAGE TOOL STORE BYRE APPROX 2 ACRES Glasgow city centre: 23.5 miles Glasgow Airport: 30 miles Edinburgh Airport: 44 miles DIRECTIONS From Glasgow continue south on the M74 taking the Junction 9 exit and follow signs into Kirkmuirhill and Blackwood. Continue into the village of Blackwood and turn left onto Thornton Road (B7086) towards Strathaven. Continue onto Strathaven Road and beyond the village of Boghead take a right turn; Woodhead Farm is the first house on the right hand side. SITUATION Woodhead Farm sits in a picturesque semi rural location overlooking surrounding farmland, yet is conveniently placed for the towns of Lesmahagow, Strathaven and Hamilton. The farmhouse, which sits close to the village of Boghead, has beautiful open aspects. There is local primary schooling at Bent Primary School and secondary schooling at Blackwood. DESCRIPTION Occupying a peaceful semi rural position within the picturesque Blackwood estate, Woodhead Farm is an elegant, traditionally built detached farmhouse built circa 1840 which is surrounded by carefully maintained mature gardens which extend to approximately 2 acres. The property is surrounded by farmland and has beautiful open aspects. The accommodation within the farmhouse is all on one level and would be ideal for two separate families or multi generational living, as there are two separate entrances, two hallways and two kitchens. -

South Lanarkshire Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Energy

South Lanarkshire Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Energy Report by IronsideFarrar 7948 / February 2016 South Lanarkshire Council Landscape Capacity Study for Wind Energy __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS 3.3 Landscape Designations 11 3.3.1 National Designations 11 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Page No 3.3.2 Local and Regional Designations 11 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 3.4 Other Designations 12 1.1 Background 1 3.4.1 Natural Heritage designations 12 1.2 National and Local Policy 2 3.4.2 Historic and cultural designations 12 1.3 The Capacity Study 2 3.4.3 Tourism and recreational interests 12 1.4 Landscape Capacity and Cumulative Impacts 2 4.0 VISUAL BASELINE 13 2.0 CUMULATIVE IMPACT AND CAPACITY METHODOLOGY 3 4.1 Visual Receptors 13 2.1 Purpose of Methodology 3 4.2 Visibility Analysis 15 2.2 Study Stages 3 4.2.1 Settlements 15 2.3 Scope of Assessment 4 4.2.2 Routes 15 2.3.1 Area Covered 4 4.2.3 Viewpoints 15 2.3.2 Wind Energy Development Types 4 4.2.4 Analysis of Visibility 15 2.3.3 Use of Geographical Information Systems 4 5.0 WIND TURBINES IN THE STUDY AREA 17 2.4 Landscape and Visual Baseline 4 5.1 Turbine Numbers and Distribution 17 2.5 Method for Determining Landscape Sensitivity and Capacity 4 5.1.1 Operating and Consented Wind Turbines 17 2.6 Defining Landscape Change and Cumulative Capacity 5 5.1.2 Proposed Windfarms and Turbines (at March 2015) 18 2.6.1 Cumulative Change -

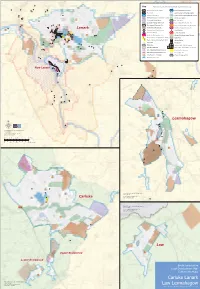

Carluke Lanark Law Lesmahagow

Key Please note: Not all of the Key elements will be present on each map South Lanarkshire Boundary Local Neighbourhood Centre River Clyde Out of Centre Commercial Location Settlement Boundary Retail / Comm Proposal Outwith Centres Strategic Economic Investment Location Priority Greenspace Community Growth Area Green Network Structural Planting within CGA New Lanark World Heritage Site Development Framework Site New Lanark World Heritage Site Buffer Lanark Residential Masterplan Site Scheduled Ancient Monument ² Primary School Modernisation Listed Building ² Secondary School Conservation Area Air Quality Management Area Morgan Glen Local Nature Reserve ±³d Electric Vehicle Charging Point (43kW) Quiet Area ±³d Electric Vehicle Charging Point (7kW) Railway Station Green Belt Bus Station Rural Area Park and Ride / Rail Interchange General Urban Area Park & Ride / Rail and Bus Interchange Core Industrial and Business Area New Road Infrastructure Other Employment Land Use Area Recycling Centre 2014 Housing Land Supply Waste Management Site Strategic Town Centre New Lanark Lesmahagow ÅN Scheduled Monuments and Listed Building information © Historic Scotland. © Crown copyright and database rights 2015. Ordnance Survey 100020730 0 0.125 0.25 0.5 Miles 0 0.2 0.4 0.8 Kilometers Scheduled Monuments, and Listed Building information © Historic Scotland. © Crown copyright and database rights 2015. Carluke Ordnance Survey 100020730 Scheduled Monuments, and Listed Building information © Historic Scotland. © Crown copyright and database rights 2015. Ordnance Survey 100020730 Law Upper Braidwood Lower Braidwood South Lanarkshire Local Development Plan Settlements Maps Carluke Lanark Scheduled Monuments, and Listed Building information © Historic Scotland. © Crown copyright and database rights 2015. Ordnance Survey 100020730 Law Lesmahagow Larkhall, Hamilton, Blantyre, Uddingston, Bothwell, on reverse. -

Weekly Planning Applications List W/C 7Th October 2019

Weekly Planning Applications List w/c 7th October 2019 Welcome to Graham + Sibbald's Weekly Planning Application List of significant applications validated the week commencing the 7th October 2019. If you require further information please contact the planning team at [email protected]. If you have been forwarded this list by a colleague and wish to receive these weekly updates, please sign up to our mailing list here. Key: Residential Energy Commercial Mixed Use Other Authority Applicant Reference Description Address Agent Date CALA Land to the SW of Aberdeenshire Management Ltd Meldrum House Council & Meldrum Erection of 36 dwellinghouses Hotel, Meldrum APP/2019/2299 House Estate House Hotel, 10/10/19 CALA Homes Oldmeldrum (North) Ltd Aberdeenshire Site east of Golden Fotheringham Council Acre, Johnshaven, Homes Erection of 71 dwellinghouses APP/2019/2255 Aberdeenshire, John D Crawford 07/10/19 DD10 0EX Ltd Dundee City Site of Whitfield George Martin Council Primary School, Builders Ltd Proposed erection of 30 new build houses 19/00776/FULL Whitfield Drive, KDM Architects 02/10/19 Dundee Ltd East Panacea Renfrewshire Treeside Cottage, Erection of 18 flats following demolition of existing Property Council Ayr Road, Newton dwellinghouse with associated formation of access Convery Prenty 2019/0606/TP Mearns, G77 6RT Architects 10/10/19 Proposal of Application Notice for housing-led, mixed- City of use development which includes conversion of existing City of Edinburgh Edinburgh Category B listed stables building into a work and events -

South Lanarkshire Council – Scotland Date (August, 2010)

South Lanarkshire Council – Scotland Date (August, 2010) 2010 Air Quality Progress Report for South Lanarkshire Council In fulfillment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management Date (August, 2010) Progress Report i Date (August, 2010) South Lanarkshire Council - Scotland ii Progress Report South Lanarkshire Council – Scotland Date (August, 2010) Local Ann Crossar Authority Officer Department Community Resources, Environmental Services Address 1st Floor Atholl House, East Kilbride, G74 1LU Telephone 01355 806509 e-mail [email protected]. uk Report G_SLC_006_Progress Report Reference number Date July 2010 Progress Report iii Date (August, 2010) South Lanarkshire Council - Scotland Executive Summary A review of new pollutant monitoring data and atmospheric emission sources within the South Lanarkshire Council area has been undertaken. The assessment compared the available monitoring data to national air quality standards in order to identify any existing exceedences of the standards. Data was gathered from various national and local sources with regard to atmospheric emissions from: road traffic; rail; aircraft; shipping; industrial processes; intensive farming operations; domestic properties; biomass plants; and dusty processes. The screening methods outlined in the technical guidance were used to determine the likelihood that a particular source would result in an exceedence of national air quality standards. The review of new and changed emission sources identified no sources that were likely to -

Monklands Network 47/47A, 200, 202*, 206*, 211, 212*, 213*, 214*, 215*, 216, 217*, 232*, 245, 247*, 287*, 310 * Timetables Updated 29Th August

Monklands Network 47/47A, 200, 202*, 206*, 211, 212*, 213*, 214*, 215*, 216, 217*, 232*, 245, 247*, 287*, 310 * Timetables updated 29th August UPDATED TIMETABLE FROM 29TH AUG GLENMAVIS 2016 KIRKINTILLOCH KIRKSHAWS AIRDRIE KIRKWOOD BARGEDDIE LANGLOAN CALDERCRUIX MILNGAVIE CHAPELHALL H MONKLANDS HOSPITAL COATBRIDGE MOODIESBURN H COATHILL HOSPITAL PLAINS CUMBERNAULD SALSBURGH FARADAY PARK SHAWHEAD GLENBOIG TOWNHEAD www.mcgillsbuses.co.uk 1 Great value unlimited tickets GoZone8 across Lanarkshire. We’ve got bus travel covered in DAY WEEK 4 WEEK 10 WEEK Monklands with our great new routes. ADULT £4.00 £16.30* £57.75 — Whether it’s to the shops, to work or to play, McGill’s can get you there! We’ve got STUDENT £2.75 £14.10 £49.35 £117.60 great value, unlimited tickets on offer too CHILD (u16s) £1.60** £6.60 £25.20 £58.80 - buy on the bus, or via our m-ticket app, and use as many times as you like across * £15.50 with m-ticketing app ** £1.00 with m-ticketing app any McGill’s bus in Monklands. Great value fares start at only 50p for a NEW FAMILY DAY TICKET £10.00 TWO ADULTS & UP TO 3 CHILDREN u16s single! We look forward to welcoming you on board! CHILD SINGLE TICKET JUST 50P For further information and timetables see our website www.mcgillsbuses.co.uk ANY BUS, ANY TIME! or call FREE on 08000 51 56 51. Bargeddie - Coatbridge 213 2 MONDAY TO SATURDAY from 29th August 2016 Service No. 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 213 Bargeddie Station 08.16 08.46 09.16 09.46 10.16 10.46 11.16 11.46 12.16 12.46 13.16 13.46 14.16 14.46 15.16 15.46 16.16 16.46 17.16 17.46 Glasgow Road at Drumpark School 08.22 08.52 09.22 09.52 10.22 10.52 11.22 11.52 12.22 12.52 13.22 13.52 14.22 14.52 15.22 15.52 16.22 16.52 17.22 17.52 Coatbridge, South Circular Road 08.30 09.00 09.30 10.00 10.30 11.00 11.30 12.00 12.30 13.00 13.30 14.00 14.30 15.00 15.30 16.00 16.30 17.00 17.30 18.00 Service No. -

Applications Identified As 'Delegated' Shall Be Dealt with Under These

Enterprise Resources Planning and Building Standards Weekly List of Planning Applications List of planning applications registered by the Council for the week ending From : - 18/08/2008 To : 22/08/2008 Note to Members: Applications identified as 'Delegated' shall be dealt with under these powers unless more than 5 objections are received or unless a representation/objection is made by a Council Member within 10 working days of the week-ending date. Any representation/objection made by a Councillor will result in that application being referred to the Area Committee for consideration. Any queries on any of the applications contained in the list or requests to refer an application to Committee should be directed to the Area Manager/Team Leader at the appropriate Area Office. Hamilton Area Tel. 01698 453518 Email [email protected] East Kilbride Area Tel. 01355 806415 Email [email protected] Clydesdale Area Tel. 01555 673206 Email [email protected] Cambuslang/Rutherglen Area Tel. 0141 613 5170 Email [email protected] Cambuslang/Rutherglen Area Office Proposed Site location Applicant Agent Cambuslang development Application ref: CR/08/0194 Installation of a Halfway & District Vodafone Ltd Mono Consultants Date registered 21/08/2008 13.44 metre high Bowling Club Ltd Area office: Cambuslang/Rutherglen "telegraph pole" Mill Road C/o Agent Powers: Area Committee 48 St Vincent telecommunications Cambuslang Grid reference: 265611 659901 Street mast with -

Old Mines and Mine Masters of the Monklands” British Mining No.45, NMRS, Pp.66-86

BRITISH MINING No.45 MEMOIRS 1992 Skillen, B.S. 1992 “Old Mines and Mine Masters of the Monklands” British Mining No.45, NMRS, pp.66-86. Published by the THE NORTHERN MINE RESEARCH SOCIETY SHEFFIELD U.K. © N.M.R.S. & The Author(s) 1992. ISSN 0309-2199 BRITISH MINING No.45 OLD MINES AND MINES MASTERS OF THE MONKLANDS Brian S. Skillen SYNOPSIS The Monklands lie east of Glasgow, across economically worthwhile coal measures, which have been worked to a great extent. Additionally to coal it proved possible to work a good local ironstone. Mushet’s blackband ironstone proved the resource on which the Monklands rose to prosperity in the 19th century. A pot pourri of minerals was there to be worked and their exploitation may be traced back to the 17th century. Estate feuding provides the first clue to the early coal working of the Monklands. In 1616, Muirhead of Brydanhill was in dispute with Newlands of Kip ps. Such was the animosity of feeling, that the latter turned up at the tiny coal working at Brydanhill and together with his men smashed up Muirhead’s pit head.1 It is likely that Muirhead’s mine had answered purely local needs and certainly if mining did continue it was on this ephemeral basis, at least until the mid 18th century. The reasons are easy to find, fragile local markets that offered no encouragement to invest in mining and a lack of communications that stopped any hope of export. In any case the western markets were then answered by the many small coal pits about the Glasgow district, including satellite workings such as Barrachnie on the western extremity of Old Monkland Parish. -

Glasgow to Easterhouse and Coatbridge Cycle Route the Monkland Cycle Route

GLASGOW TO EASTERHOUSE AND COATBRIDGE CYCLE ROUTE THE MONKLAND CYCLE ROUTE (Updated June 2009) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Buchanan Bus Station to Coatbridge Fountain without cycling on any main roads! • Serves Glasgow City Centre, Caledonian University, Buchanan Bus Station, Strathclyde University, Royal Infirmary, Alexandra Park, Cranhill Park, Blairtummock Industrial Estate, Glasgow Fort Shopping Centre, Blairtummock Park, Monkland Canal, Drumpellier Country Park, The Time Capsule, Coatbridge Town Centre, plus numerous schools and local shopping areas • Large catchment area serving North East Glasgow, not presently served by any cycle route • Links Glasgow City Centre, Roystonhill, North Dennistoun, North Carntyne, Cranhill, Queenslie, Garthamlock, Easthall, Easterhouse, North Bargeddie, Drumpellier, Coatbridge Town Centre • Connects with existing Colleges Cycle Route, Glasgow to Cumbernauld Cycle Route, National Cycle Network Route 75, the Garthamlock ramp (currently under design), plus potential links to various communities near route • Potential candidate for Sustrans “Regional Cycle Network” route status, thus allowing route to be marked on Ordnance Survey maps • Utilises existing paths and quiet roads over most of route • Limited construction work required to link up existing infrastructure • Caters for those cyclists not catered for by Quality Bus Corridor (Streamline) routes • Reasonably direct route, parallel to M8 motorway Go Bike! Strathclyde Cycle Campaign • PO Box 15175 • Glasgow • G4 9LP • www.gobike.org GLASGOW TO EASTERHOUSE AND COATBRIDGE CYCLE ROUTE THE MONKLAND CYCLE ROUTE Route description: Starting at George Square in Glasgow City Centre, the route proceeds via Townhead, Roystonhill, North Dennistoun, Alexandra Park, North Carntyne, Cranhill, Queenslie, Easthall, Blairtummock Park, North Bargeddie, and the Monkland Canal to Coatbridge Town Centre. There are also links to Greenfield Park from North Carntyne, and to the Glasgow Fort and Easterhouse Shopping Centres. -

SCOTTISH INDUSTRIAL HISTORY Volume 6.1 1983 S C 0 T T I S H

SCOTTISH INDUSTRIAL HISTORY Volume 6.1 1983 S C 0 T T I S H I N D U S T R I A L H I S T 0 R Y Volune 6. 1 1983 Scottish Indystrial Hi2tory is published twice annually by the Scottish Society for Industrial History, the Scottish Society for the Preservation of Historical Machinery and the Business Archives Council of Scotland. The editors are: Mrs. S. Clark, Paisley; Dr. C.W. Munn and Mr. A.T. Wilson, University of Glasgow. Proof-reading was carried out by Mr. M. Livingstone, Business Archives Council of Scotland. Front (;over: Paddle Steamer Engine Back Cover: Horizontal Driving Engine Both constructed by A.F. Craig and Company Ltd., Paisley. (Our thanks to Mr. W.S. Harvey for lending the original photographs) . S C 0 T T I S H I N D U S T R I A L H I S T 0 R Y Voltllle 6.1 1983 Content.s Some brief notes on the History of James Young Ltd., and James Young and Sons Ltd., Railway and Public Works Contractors. N.J. Horgan 2 The Iron Industry of the Monklands (continued): The Individual Ironworks George Thanson 10 Markets and Entrepreneurship in Granite Quarrying in North East Scotland 1750-1830 Tan Donnelly 30 Summary Lists of Archive Surveys and Deposits 46 Book Reviews 60 Corrigenda 65 2 Sane brief notes on the history of Janes Young Ltd, and Janes Young & Sons Ltd, Railway and Public Works Contractors by N.J. K>RGAN During the late nineteenth century the Scottish contracting industry was effectively dominated by a handful of giants. -

South Lanarkshire Council Present

South Lanarkshire Council South Lanarkshire Local RAUC Meeting, 19 August 2020 – Meeting No. 45 Present: David Carter DC South Lanarkshire Council (Chair) Valerie Park VP South Lanarkshire Council Graeme Peacock GP SGN Glasgow Stewart Allan SA AMEY M8/M73/M74/DBFO David Fleming DF TTPAG DBFO David Murdoch DM Network Rail Emma West EW Scottish Water Collette Findlay CF SGN Coatbridge Joao Carmo JC SPEN John McCulloch JMcC Balfour Beatty Owen Harte OH Virgin Media Stephen Scanlon SS OpenReach Steven McGill SMcG Fulcrum Neil Brannock NB Autolink M6 Scott Bunting SB SSE Craig McTiernan CMcT Axione Gordon Michie GM Scottish Water Note – apologies were received but not noted. Additional Circulation to: George Bothwick Action No. Description By 1.0 Introductions and Apologies NOTE – These minutes are from 19th February – attendance list accurate for Noted August meeting 2.0 Agree Previous Minutes – 19 February 2020 Minutes agreed from previous meeting as accurate. Noted 3.0 Matters Arising from Previous Minutes Increased numbers of DA and unattributable works notices Noted VP 4.0 Performance 4.1 All OD Performance Page 1 of 6 South Lanarkshire Council South Lanarkshire Local RAUC Meeting, 19 August 2020 – Meeting No. 45 Action No. Description By Outstanding defect report distributed prior to the meeting for discussion. ALL VP noted that in recent months Openreach, Virgin Media and SGN have made good progress in clearing some of their outstanding defects. VP advised that there is an increasing number of Defective Apparatus and Unattributable works notices still recorded against the SL001 channel awaiting acceptance from relevant Utilities (approx. 100).