Inquiry Into the Provision of Child Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Exchange of Letters Between RR and ABC Management About

Rory Robertson August 2017 2017 exchange of letters between RR and ABC management about whether or not secret ABC investigation into Lateline’s Australian Paradox report should be available on ABC’s website Readers, I think you should be aware that professional scientists from the University of Sydney in May 2016 wrote a 36-page formal letter of complaint about Emma Alberici’s ABC TV Lateline report that shredded the credibility of their extraordinarily faulty Australian Paradox paper http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/content/2015/s4442720.htm In September 2016, Professor Jennie Brand-Miller and Dr Alan Barclay were advised via a 15-page official ABC response that an independent Audience and Consumer Affairs (A&CA) investigation had confirmed the Lateline report to be accurate and impartial on all reported matters of fact. Last November, I requested a copy of the secret ABC report. So far, the ABC has chosen to suppress the report. Readers, I'm arguing on public-health grounds that (i) it is in the community's interest to know that Professor Brand-Miller and Dr Barclay wrote a 36-page formal letter of complaint about the Lateline report that shredded the credibility of their Australian Paradox “finding”; and (ii) the community should be allowed to know that the ABC’s formal investigation confirmed the accuracy of reports of profound flaws, including the paper’s use of fake data. Unfortunately, after being advised of the profound problems, instead of properly correcting the formal scientific record, Brand-Miller and Barclay have continued to pretend that their widely-cited paper is essentially flawless. -

2018 SWF Live and Local Speakers April 18, 2018

2018 SWF Live and Local Speakers April 18, 2018 Name Bio Recent works Alec Luhn is the Russia correspondent for The Daily Telegraph and has previously written for Time, Politico, The New York Times and The Guardian , among others. He covered the Russian protest Alec Luhn movement, the Sochi Olympics, the annexation of Crimea and the revolution and war in Ukraine. He is working on a book related to the Russian interference in the 2016 US election. Alexis Okeowo is a magazine writer and screenwriter, and a former fellow at New America. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine , the Financial Times , The Best American Travel Writing , and The Best American Sports Writing . The daughter of immigrant parents, Okeowo grew Alexis A Moonless, Starless Sky: Ordinary Women up in Alabama and attended Princeton University. She was based in Lagos, Nigeria, from 2012 to 2015, Okeowo and Men Fighting Extremism in Africa and now lives in Brooklyn. Her first book, A Moonless, Starless Sky: Ordinary Women and Men Fighting Extremism In Africa , is a vivid narrative of Africans who are courageously resisting their continent’s wave of fundamentalism. Aminatou Sow is founder of Tech LadyMafia, a group that increases opportunities for women in Tech and the co-host of Call Your Girlfriend , a podcast that tackles the intricacies of pop culture and the latest in Aminatou politics every single week. A digital strategist and writer, she was named one of Forbes 30 Under 30 in Sow Tech. She is also a member of the Sundance Institute Director's Advisory Group and previously led Social Impact Marketing at Google. -

The Finkelstein Inquiry: Miscarried Media Regulation Moves Miss Golden Reform Opportunity

Vol 4 The Western Australian Jurist 23 THE FINKELSTEIN INQUIRY: MISCARRIED MEDIA REGULATION MOVES MISS GOLDEN REFORM OPPORTUNITY * JOSEPH M FERNANDEZ Laws are generally found to be nets of such a texture, as the little creep through, the great break through, and the middle-sized are alone entangled in.1 Abstract The Australian media’s nervous wait for the outcome of media regulation reform initiatives came to an abrupt and ignominious end in March 2013 as the moves collapsed. The Federal Government withdrew a package of Bills at the eleventh hour, when it became apparent that the Bills would not garner the required support in parliament. These Bills were preceded by two major media inquiries – the Convergence Review and the Independent Media Inquiry – culminating in reports released in 2012. The latter initiative contained sweeping reform recommendations, including one for the formation of a government-funded ‘super regulator’ called the News Media Council, which the media generally feared would spell doom especially for those engaged in the ‘news’ business. This article examines the origins of the Independent Media Inquiry; the manner of the inquiry’s conduct; what problem the inquiry was seeking to address; the consequent recommendations; and ultimately, the manoeuvres for legislative action and the reform initiative’s demise. This article concludes that the Independent Media Inquiry was flawed from the outset and * Head of Journalism, Curtin University. This article is developed from a presentation by the author to the Threats to Freedom of Speech Conference hosted by the Murdoch University Law School on 12 October 2012 at Perth, Western Australia. -

Australia Turns to ABC for #Libspill

RELEASED: Tuesday 15 September, 2015 Australia turns to ABC for #libspill Australian audiences turned to the ABC for rolling news and analysis of Malcolm Turnbull’s party room victory over Tony Abbott to become Prime Minister on Monday night, again demonstrating why the ABC is the country’s most trusted source of news. Last night’s leadership spill saw the ABC pull together resources across TV, Radio, Digital, and International divisions to provide audiences with the most comprehensive coverage of events as they unfolded. At a total network level, ABC TV reached 4.2 million metro viewers last night (between 6pm and midnight), with a primetime share of 23.3%. ABC was the number one channel from 8.30pm onwards. With continuous coverage of events in Canberra, there were 197,500 plays of the ABC News 24 live stream via the website and iview, the highest this year-to-date. ABC News recorded its highest online traffic for the year-to-date (desktop and mobile), with 1.5 million visitors, 2.1 million visits and 5.8 million page views, each up more than 80% on the same time last week. The ABC News Live Blog recorded 710,900 visits. Australian expats abroad and regional audiences were also kept informed with ABC International providing rolling multilingual coverage across platforms including Australia Plus television, online and social media sites, Radio Australia, and numerous syndication media platforms across Asia and the Pacific. ABC Radio highlighted its agility and strength, with robust coverage on ABC Local Radio, NewsRadio and RN. The Local Radio coverage was adapted to broadcast a single national evening’s program, with expert analysts and talkback callers around the country, giving the audience a strong sense of the national dialogue. -

Budget 2017: ABC Coverage on TV, Iview, Radio and Online

Media Release: 05.05.17 Budget 2017: ABC Coverage on TV, iview, radio and online abc.net.au/news The 2017 Federal Budget will be handed down on Tuesday May 9 and the ABC has the best independent coverage on all platforms. We’ll have the first interview with Treasurer Scott Morrison, as well as in-depth analysis and expert commentary from the ABC’s leading political and business teams. What does Budget 2017 mean for you? Know the numbers, the politics, and the impact with ABC NEWS. Tuesday, 9 May – BUDGET DAY TELEVISION – ABC, the ABC NEWS channel & iview The Drum - 5.30pm on ABC & iview / 6.30pm AEST on the ABC NEWS channel As the press gallery bunkers down in the budget media lock-up, host John Barron and a panel of experts will count down to Budget 2017 and preview what to expect. ABC NEWS - 7pm on ABC & iview The news of the day and the lead up to the Federal Treasurer’s Budget speech. ABC NEWS BUDGET 2017 SPECIAL - on ABC, the ABC NEWS channel, iview, ABC NEWS online and simulcast live on the ABC News Facebook page. Leigh Sales hosts the ABC NEWS Budget 2017 special with Political Editor Chris Uhlmann live from Parliament House in Canberra. At 7:30pm AEST the Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison will deliver his second Federal Budget speech live from the House of Representatives. Just after 8pm, Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison will join Leigh Sales for his first interview of the night, followed by the response from the Opposition’s Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen. -

I Never Took Myself Seriously As a Writer Until I Studied at Macquarie.” LIANE MORIARTY MACQUARIE GRADUATE and BEST-SELLING AUTHOR

2 swf.org.au RESEARCH & ENGAGEMENT 1817 - 2017 luxury property sales and rentals THE UN OF ITE L D A S R T E A T N E E S G O E F T A A M L E U R S I N C O A ●C ● SYDNEY THE LIFTED BROW Welcome 3 SWF 2017 swf.org.au A Message from the Artistic Director Contents eading can be a mixed blessing. For In a special event, writer and photographer 4-15 anyone who has had the misfortune Bill Hayes talks to Slate’s Stephen Metcalf about City & Walsh Bay to glance at the headlines recently, Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me, an the last few months have felt like a intimate love letter to New York and his late Guest Curators 4 long fever dream, for reasons that partner, beloved writer and neurologist extend far beyond the outcome of the Oliver Sacks. R Bernadette Brennan has delved into 7 US Presidential election or Brexit. Nights at Walsh Bay More than 20 million refugees are on the move the career of one of Australia’s most adept and another 40 million people are displaced in and admired authors, Helen Garner, with Thinking Globally 11 their own countries, in the largest worldwide A Writing Life. An all-star cast of Garner humanitarian crisis since 1945. admirers – Annabel Crabb, Benjamin Law Scientists announced that the Earth reached and Fiona McFarlane – will join Bernadette City & Walsh Bay its highest temperatures in 2016 – for the third in conversation with Rebecca Giggs about year in a row. -

Canberra Writers Festival Program 2018

Power Politics Passion | The Annual 1canberrawritersfestival.com.au | 23-26 August 2018 “ And so your story is imperfect, Sandra, but it is here, made complete, and it is my love letter to you. — Sarah Krasnostein, The Trauma Cleaner Photography: Martin Ollman SPECIAL EVENT SUNDAY 26 AUGUST 6.00PM – 7.30PM LLEWELLYN HALL, ANU Girls’ Tearing up the stage is five outrageously Night In funny, smart and talented women to mark the Festival’s closing event – Girls’ Kathy Lette, Night In! Bringing their unique brand of humour and whip-smart observations on Annabel Crabb, the whimsy of life – and the meagre role Nikki Gemmell, played by men of all ages – these dames Bridie Jabour and will have you in stitches as they chew the fat and share their love of literature, moderated by fine art, music and aged cognac. Kick Jean Kittson off your heels (boys too), laugh with gusto and celebrate the end of the 2018 SPECIAL EVENT Canberra Writers Festival! One on One Matthew Reilly In Conversation with Emma Alberici SUNDAY 26 AUGUST over 7.5 million copies of his books 1.OOPM – 2.00PM based on self-belief, self-publishing and LLEWELLYN HALL, ANU a passion action thrilling plots. His story is also one of great personal pain and the Exclusive to the Canberra Writers courage and strength required to move Festival, Matthew Reilly flies in and out forward. Matthew talks with highly of the country for one session only One respected ABC journalist and television on One in Canberra. Matthew’s story presenter, Emma Alberici. is one of extraordinary success selling 2 Power Politics Passion | The Annual canberrawritersfestival.com.au | 23-26 August 2018 WELCOME They join an incredible Australian ACT Chief Festival line-up including US-based action- thriller writer Matthew Reilly, who is Minister Directors flying in from LA for an exclusive with the CWF; former Prime Minister John by ANDREW BARR by JENNY BOTT and Howard will speak to his new book The PAUL DONOHOE Art of Persuasion while Annabel Crabb elcome to the 3rd Canberra joins UK-based writer Kathy Lette on Writers Festival. -

Bitch the Politics of Angry Women

Bitch The Politics of Angry Women Kylie Murphy Bachelor of Arts with First Class Honours in Communication Studies This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2002. DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Kylie Murphy ii ABSTRACT ‘Bitch: the Politics of Angry Women’ investigates the scholarly challenges and strengths in retheorising popular culture and feminism. It traces the connections and schisms between academic feminism and the feminism that punctuates popular culture. By tracing a series of specific bitch trajectories, this thesis accesses an archaeology of women’s battle to gain power. Feminism is a large and brawling paradigm that struggles to incorporate a diversity of feminist voices. This thesis joins the fight. It argues that feminism is partly constituted through popular cultural representations. The separation between the academy and popular culture is damaging theoretically and politically. Academic feminism needs to work with the popular, as opposed to undermining or dismissing its relevancy. Cultural studies provides the tools necessary to interpret popular modes of feminism. It allows a consideration of the discourses of race, gender, age and class that plait their way through any construction of feminism. I do not present an easy identity politics. These bitches refuse simple narratives. The chapters clash and interrogate one another, allowing difference its own space. I mine a series of sites for feminist meanings and potential, ranging across television, popular music, governmental politics, feminist books and journals, magazines and the popular press. -

INSTITUTION EMPLOYMENT COMMENTS a Eurydice Aroney

INSTITUTION EMPLOYMENT COMMENTS A Eurydice Aroney UTS UTS staff Walkley award winner Desmond Ang RMIT CNBC Asia, Singapore Tahlia Azaria RMIT SYN Media Melissa Abalo RMIT ABC MIchelle AInsworth RMIT Herald SUn Elizabeth Allen RMIT Leader Sarah Paige Ashmore RMIT 3AW Emma Alberici Deakin Lateline presenter Deakin University's Colleen Murrell writes: " I interviewed her last year ...and she spoke very highly of her journalism course." B Mark Baker RMIT Fairfax (national "The course began as managing editor) an industry collaboration. All Age and HWT cadets were sent part time. The program was heavily oriented to practical newspaper reporting, law and ethics - and statistics was a compulsory unit. It was run by two veteran newspapermen - Lyle Tucker of HWT and Les Hoffman, a former editor of the Straits Times and escapee from Lee Kuan Yew." Rachel Brown RMIT ABC London correspondent Dougal Beatty RMIT WIN Bendigo Luke Buckmaster La Trobe Crikey Emily Boyle CSU Tenterfield Star "It was good. Had a strong practical focus. More needed on social media." Eleanor Bell RMIT ABC Emily Bourke RMIT ABC Kelly Burke UTS Sydney Morning Herald Cynthia Banham UTS Sydney Morning Herald Paul Biddy UTS Sydney Morning Herald SAm Brett UTS Sydney Morning Herald Matt Brown UTS ABC Sarah Burnett UTS WIN Renee Bogatko University of Canberra Prime 7 Michael Brissenden University of Canberra ABC John Bannon University of Canberra Prime Clayton Bennett RMIT Sun Newspapers NT Craig Butt Monash The Age Jon Burton RMIT Herald Sun - head of iPad development John Michael Bric RMIT NOVA Sydney Laura Bevis RMIT ABC Julian Bayard RMIT CrocMedia Timothy Beissmann RMIT Caradvice.com.au Clayton Charles Bennett RMIT Darwin Sun Rosemary Bolger RMIT Leader Samuel Bolitho RMIT ABC Mitchel Brown RMIT Leader Emma Lennox Buckley RMIT Fairfax Ian Burrows RMIT ABC Erin Byrnes RMIT Benalla Ensign C Amy Coopes Charles Sturt University Australian Federal "The course.. -

Legislative Assembly Fifty-Ninth Parliament First Session Tuesday, 4 February 2020

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION TUESDAY, 4 FEBRUARY 2020 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier ........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Minister for Mental Health The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Emergency Services ............... The Hon. J Symes, MLC Minister for Transport Infrastructure and Minister for the Suburban Rail Loop ........................................................ The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Training and Skills, and Minister for Higher Education .... The Hon. GA Tierney, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development and Minister for Industrial Relations ........................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Roads and Road Safety .. The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................. The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers ....................................................... The Hon. LA Donnellan, MP Minister for Health, Minister for Ambulance Services and Minister for Equality .................................................... -

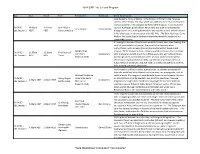

2018 SWF Live & Local Program *THIS

2018 SWF Live & Local Program Day Start Finish Title Presenter/s Facilitator Event Information Jane Harper’s Force of Nature is the follow-up thriller to the runaway success of her debut, The Dry, which was sold into more than 20 countries and optioned for a film adaption by Reese Witherspoon. It continues the Fri 04/05 - 10.00am 11.00am Jane Harper: story of Australian police officer Aaron Falk, this time as he traces the Jane Harper Claire Nichols L&L Session 1 AEST AEST Force of Nature disappearance of a missing bushwalker who was the crucial whistle-blower in his latest case. In conversation with ABC RN’s The Book Hub host Claire Nichols, the bestselling Australian author talks about the book and her remarkable success. Xi Jinping has become China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong. But with his consolidation of power, the country has become more authoritarian, with increasing censorship and arrests of lawyers and Minglu Chen activists. Three Festival authors uniquely placed to discuss China sit down Fri 04/05 - 11.30am 12.30pm The Future of Xue Yiwei Linda Jaivin with Linda Jaivin to talk about its political, economic and cultural future. L&L Session 2 AEST AEST China Robert E. Kelly Join Minglu Chen, senior lecturer at the Chinese Studies Centre at the University of Sydney; Robert E. Kelly, a professor of political science at Pusan National University; and Xue Yiwei, a prolific Chinese-born novelist, for a riveting and timely discussion. North Korea is unlike any other nation today. Its citizens are sealed off from the world and only allowed access to state-run propaganda, and its Michael Pembroke volatile leader Kim Jong-un is considered a threat to world peace. -

Sydney Writers' Festival

Bibliotherapy LET’S TALK WRITING 16-22 May 1HERSA1 S001 2 swf.org.au SYDNEY WRITERS’ FESTIVAL GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES SUPPORTERS Adelaide Writers’ Week THE FOLLOWING PARTNERS AND SUPPORTERS Affirm Press NSW Writers’ Centre Auckland Writers & Readers Festival Pan Macmillan Australia Australian Poetry Ltd Penguin Random House Australia The Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance Perth Writers Festival CORE FUNDERS Black Inc. Riverside Theatres Bloomsbury Publishing Scribe Publications Brisbane Powerhouse Shanghai Writers’ Association Brisbane Writers Festival Simmer on the Bay Byron Bay Writers’ Festival Simon & Schuster Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre State Library of NSW Créative France The Stella Prize Griffith REVIEW Sydney Dance Lounge Harcourts International Conference Text Publishing Hardie Grant Books University of Queensland Press MAJOR PARTNERS Hardie Grant Egmont Varuna, the National Writers’ House HarperCollins Publishers Walker Books Hachette Australia The Walkley Foundation History Council of New South Wales Wheeler Centre Kinderling Kids Radio Woollahra Library and Melbourne University Press Information Service Musica Viva Word Travels PLATINUM PATRON Susan Abrahams The Russell Mills Foundation Rowena Danziger AM & Ken Coles AM Margie Seale & David Hardy Dr Kathryn Lovric & Dr Roger Allan Kathy & Greg Shand Danita Lowes & David Fite WeirAnderson Foundation GOLD PATRON Alan & Sue Cameron Adam & Vicki Liberman Sally Cousens & John Stuckey Robyn Martin-Weber Marion Dixon Stephen, Margie & Xavier Morris Catherine & Whitney Drayton Ruth Ritchie Lisa & Danny Goldberg Emile & Caroline Sherman Andrea Govaert & Wik Farwerck Deena Shiff & James Gillespie Mrs Megan Grace & Brighton Grace Thea Whitnall PARTNERS The Key Foundation SILVER PATRON Alexa Haslingden David Marr & Sebastian Tesoriero RESEARCH & ENGAGEMENT Susan & Jeffrey Hauser Lawrence & Sylvia Myers Tony & Louise Leibowitz Nina Walton & Zeb Rice PATRON Lucinda Aboud Ariane & David Fuchs Annabelle Bennett Lena Nahlous James Bennett Pty Ltd Nicola Sepel Lucy & Stephen Chipkin Eva Shand The Dunkel Family Dr Evan R.