JSCA 7.2 Jag Är Ingrid Interview Open Access Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director. -

Notes on Ingmar Bergman's Stylistic

Notes on Ingmar Bergman’s Stylistic Development and Technique for Staging Dialogue Riis, Johannes Published in: Kosmorama Publication date: 2019 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: Unspecified Citation for published version (APA): Riis, J. (2019). Notes on Ingmar Bergman’s Stylistic Development and Technique for Staging Dialogue. Kosmorama, (275), [275]. https://www.kosmorama.org/notes-on-ingmar-bergman Download date: 06. okt.. 2021 10.10.2020 Notes on Ingmar Bergman’s Stylistic Development and Technique for Staging Dialogue | Kosmorama Notes on Ingmar Bergman’s Stylistic Development and Technique for Staging Dialogue PEER REVIEWED. Ingmar Bergman is heralded as a model for cinema as personal expression. What rarely comes to the fore is the extent to which he drew on pre- existing schemas for his characters and how he developed staging techniques that would suit his existentialist themes. 24. april 2019 Johannes Riis By staging his actors frontally during their delivery, Ingmar Bergman fostered a tone of intimacy and vulnerabilty, allowing a calmness around their dialogue. Here Alma (Bibi Andersson) and Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann) in 'Persona' (1966). Still: DFI Stills & Posters Archive. The March 1960 cover of Time Magazine cast Ingmar Bergman in the part of a visionary who stares into a brightly lit future while the background suggests darker demons in the woods. Were it not for the tilt of his thumb and forefinger, held up to his eye as if to frame the world, and the headline declaring ‘INGMAR BERGMAN - MOVIE DIRECTOR’, the subscribers might have mistaken him for a philosopher or author. -

POPULAR DVD TITLES – As of JULY 2014

POPULAR DVD TITLES – as of JULY 2014 POPULAR TITLES PG-13 A.I. artificial intelligence (2v) (CC) PG-13 Abandon (CC) PG-13 Abduction (CC) PG Abe & Bruno PG Abel’s field (SDH) PG-13 About a boy (CC) R About last night (SDH) R About Schmidt (CC) R About time (SDH) R Abraham Lincoln: Vampire hunter (CC) (SDH) R Absolute deception (SDH) PG-13 Accepted (SDH) PG-13 The accidental husband (CC) PG-13 According to Greta (SDH) NRA Ace in the hole (2v) (SDH) PG Ace of hearts (CC) NRA Across the line PG-13 Across the universe (2v) (CC) R Act of valor (CC) (SDH) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 1-4 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 5-8 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 9-12 (4v) PG-13 Adam (CC) PG-13 Adam Sandler’s eight crazy nights (CC) R Adaptation (CC) PG-13 The adjustment bureau (SDH) PG-13 Admission (SDH) PG Admissions (CC) R Adoration (CC) R Adore (CC) R Adrift in Manhattan R Adventureland (SDH) PG The adventures of Greyfriars Bobby NRA Adventures of Huckleberry Finn PG-13 The adventures of Robinson Crusoe PG The adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA An affair to remember (CC) NRA The African Queen NRA Against the current (SDH) PG-13 After Earth (SDH) NRA After the deluge R After the rain (CC) R After the storm (CC) PG-13 After the sunset (CC) PG-13 Against the ropes (CC) NRA Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The definitive collection (12v) PG The age of innocence (CC) PG Agent -

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

GSC Films: S-Z

GSC Films: S-Z Saboteur 1942 Alfred Hitchcock 3.0 Robert Cummings, Patricia Lane as not so charismatic love interest, Otto Kruger as rather dull villain (although something of prefigure of James Mason’s very suave villain in ‘NNW’), Norman Lloyd who makes impression as rather melancholy saboteur, especially when he is hanging by his sleeve in Statue of Liberty sequence. One of lesser Hitchcock products, done on loan out from Selznick for Universal. Suffers from lackluster cast (Cummings does not have acting weight to make us care for his character or to make us believe that he is going to all that trouble to find the real saboteur), and an often inconsistent story line that provides opportunity for interesting set pieces – the circus freaks, the high society fund-raising dance; and of course the final famous Statue of Liberty sequence (vertigo impression with the two characters perched high on the finger of the statue, the suspense generated by the slow tearing of the sleeve seam, and the scary fall when the sleeve tears off – Lloyd rotating slowly and screaming as he recedes from Cummings’ view). Many scenes are obviously done on the cheap – anything with the trucks, the home of Kruger, riding a taxi through New York. Some of the scenes are very flat – the kindly blind hermit (riff on the hermit in ‘Frankenstein?’), Kruger’s affection for his grandchild around the swimming pool in his Highway 395 ranch home, the meeting with the bad guys in the Soda City scene next to Hoover Dam. The encounter with the circus freaks (Siamese twins who don’t get along, the bearded lady whose beard is in curlers, the militaristic midget who wants to turn the couple in, etc.) is amusing and piquant (perhaps the scene was written by Dorothy Parker?), but it doesn’t seem to relate to anything. -

Swedish Film Magazine #1 2009

Swedish Film IN THE MOOD FOR LUKAS Lukas Moodysson’s Mammoth ready to meet the world Nine more Swedish films at the Berlinale BURROWING | MR GOVERNOR THE EAGLE HUNTEr’s SON | GLOWING STARS HAVET | SLAVES | MAMMA MOO AND CROW SPOT AND SPLODGE IN SNOWSTORM | THE GIRL #1 2009 A magazine from the Swedish Film Institute www.sfi.se Fellow Designers Internationale Filmfestspiele 59 Berlin 05.–15.02.09 BERLIN INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2009 OFFICIAL SELECTION IN COMPETITION GAEL GARCÍA BERNAL MICHELLE WILLIAMS MA FILMA BYM LUKMAS MOOODTYSSHON MEMFIS FILM COLLECTION PRODUCED BY MEMFIS FILM RIGHTS 6 AB IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH ZENTROPA ENTERTAINMENTS5 APS, ZENTROPA ENTERTAINMENTS BERLIN GMBH ALSO IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH FILM I VÄST, SVERIGES TELEVISION AB (SVT), TV2 DENMARK SUPPORTED BY SWEDISH FILM INSTITUTE / COLLECTION BOX / SINGLE DISC / IN STORES 2009 PETER “PIODOR” GUSTAFSSON, EURIMAGES, NORDIC FILM & TV FUND/HANNE PALMQUIST, FFA FILMFÖRDERUNGSANSTALT, MEDIENBOARD BERLIN-BRANDENBURG GMBH, DANISH FILM INSTITUTE/ LENA HANSSON-VARHEGYI, THE MEDIA PROGRAMME OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Fellow Designers Internationale Filmfestspiele 59 Berlin 05.–15.02.09 BERLIN INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2009 OFFICIAL SELECTION IN COMPETITION GAEL GARCÍA BERNAL MICHELLE WILLIAMS MA FILMA BYM LUKMAS MOOODTYSSHON MEMFIS FILM COLLECTION PRODUCED BY MEMFIS FILM RIGHTS 6 AB IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH ZENTROPA ENTERTAINMENTS5 APS, ZENTROPA ENTERTAINMENTS BERLIN GMBH ALSO IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH FILM I VÄST, SVERIGES TELEVISION AB (SVT), TV2 DENMARK SUPPORTED BY SWEDISH FILM INSTITUTE -

Emmy Award Winners

CATEGORY 2035 2034 2033 2032 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Limited Series Title Title Title Title Outstanding TV Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title CATEGORY 2031 2030 2029 2028 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. -

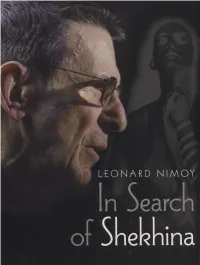

Nimoy-Two.Pdf

Leonard Nimoy, reknowned for his portrayal of the Vul Moment: I've heard that the famous Vulcan can Mr. Spock on the original Star Trek television series, greeting came straight from Judaism. Is this so? set aside a highly acclaimed career as an actor and direc NlMOY: In 1966 Star Trek went on the air and I'm tor to pursue the latest segment of his "Jewish journey? playing a Vulcan. Late in the season we get litis won For nearly a decade Nimoy, now 70, has photographed and derful script by a very talented poetic writer named developed images of the feminine presence of God, culmi Theodore Sturgeon called Amok Time, burl Tinn nating in a book of controversial photographs titled was a story where we discovered that my character • Shekhina. The son of a barber, Nimoy grew up in an Spock—had been betrothed as a child ami had u> p.> Orthodox family in Boston and once thought of pursuing back to his home planet of Vulcan to fulfill the mar a full-time career as a photographer. The Jewish Muse riage contract. We go to the planet, the fj irvc i if us— um in New York recently purchased one of his photographs William Shatner as Captain Kirk, De Fiirvsf Ki-lla for its permanent collection, and on February 10, 2004, as Dr. McCoy and myself. We are met liv ,1 proces "Shekhina," a dance based on Nimoy sphotographs, will sion led by several men who are can \ inn von rcg.il be performed at the Joyce Theater in New York City. -

![Lucy Kroll Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3113/lucy-kroll-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-2283113.webp)

Lucy Kroll Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Lucy Kroll Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2002 Revised 2010 April Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms006016 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm82078576 Prepared by Donna Ellis with the assistance of Loren Bledsoe, Joseph K. Brooks, Joanna C. Dubus, Melinda K. Friend, Alys Glaze, Harry G. Heiss, Laura J. Kells, Sherralyn McCoy, Brian McGuire, John R. Monagle, Daniel Oleksiw, Kathryn M. Sukites, Lena H. Wiley, and Chanté R. Wilson Collection Summary Title: Lucy Kroll Papers Span Dates: 1908-1998 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1950-1990) ID No.: MSS78576 Creator: Kroll, Lucy Extent: 308,350 items ; 881 containers plus 15 oversize ; 356 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Literary and talent agent. Contracts, correspondence, financial records, notes, photographs, printed matter, and scripts relating to the Lucy Kroll Agency which managed the careers of numerous clients in the literary and entertainment fields. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Braithwaite, E. R. (Edward Ricardo) Davis, Ossie. Dee, Ruby. Donehue, Vincent J., -1966. Fields, Dorothy, 1905-1974. Foote, Horton. Gish, Lillian, 1893-1993. Glass, Joanna M. Graham, Martha. Hagen, Uta, 1919-2004. -

Woody Loves Ingmar

1 Woody loves Ingmar Now that, with Blue Jasmine , Woody Allen has come out … … perhaps it’s time to dissect all his previous virtuoso creative adapting. I’m not going to write about the relationship between Vicky Christina Barcelona and Jules et Jim . ————— Somewhere near the start of Annie Hall , Diane Keaton turns up late for a date at the cinema with Woody Allen, and they miss the credits. He says that, being anal, he has to see a film right through from the very start to the final finish, so it’s no go for that movie – why don’t they go see The Sorrow and the Pity down the road? She objects that the credits would be in Swedish and therefore incomprehensible, but he remains obdurate, so off they go, even though The Sorrow and the Pity is, at over four hours, twice the length of the film they would have seen. 2 The film they would have seen is Ingmar Bergman’s Face to Face , with Liv Ullmann as the mentally-disturbed psychiatrist – you see the poster behind them as they argue. The whole scene is a gesture. Your attention is being drawn to an influence even while that influence is being denied: for, though I don’t believe Bergman has seen too much Allen, Allen has watched all the Bergman there is, several times over. As an example: you don’t often hear Allen’s early comedy Bananas being referred to as Bergman-influenced: but not only does its deranged Fidel Castro-figure proclaim that from now on the official language of the revolutionised country will be Swedish, but in the first reel there’s a straight Bergman parody. -

Publications Editor Prized Program Contributors Tribute Curator

THE NATIONAL FILM PRESERVE LTD. presents the Julie Huntsinger Directors Tom Luddy Gary Meyer Michael Ondaatje Guest Director Muffy Deslaurier Director of Support Services Brandt Garber Production Manager Bonnie Luftig Events Manager Bärbel Hacke Hosts Manager Shannon Mitchell Public Relations Manager Marc McDonald Theatre Operations Manager Lucy Lerner ShowCorps Manager Erica Gioga Housing/Travel Manager Kate Sibley Education Programs Dean Elizabeth Temple V.P., Filmanthropy Melissa DeMicco Development Manager Kirsten Laursen Executive Assistant to the Directors Technical Direction Russell Allen Sound, Digital Cinema Jon Busch Projection Chapin Cutler Operations Ross Krantz Chief Technician Jim Bedford Technical Coordinator Annette Insdorf Moderator Pierre Rissient Resident Curators Peter Sellars Paolo Cherchi Usai Godfrey Reggio Publications Editor Jason Silverman (JS) Prized Program Contributors Larry Gross (LG), Lead Writer Sheerly Avni (SA), Serge Bromberg (SB), Meredith Brody (MB), Paolo Cherchi Usai (PCU), Jesse Dubus (JD), Roger Ebert (RE), Scott Foundas (SF), Kirk Honeycutt (KH), Tom Luddy (TL), Jonathan Marlow (JM), Greil Marcus (GM), Gary Meyer (GaM), Michael Ondaatje (MO), Milos Stehlik (MS) Tribute Curator Chris Robinson 1 Shows The National Film Preserve, Ltd. A Colorado 501(c)(3) non-profit, tax-exempt educational corporation 1a S/Fri 6:30 PM - G/Sat 9:30 AM - 1b L/Sun 6:45 PM Founded in 1974 by James Card, Tom Luddy and Bill & Stella Pence 1 A Tribute to Peter Weir Directors Emeriti Bill & Stella Pence Board of Governors Peter Becker, Ken Burns, Peggy Curran, Michael Fitzgerald, Julie Huntsinger, Linda Lichter, Tom Luddy, Gary Meyer, Elizabeth Redleaf, Milos Stehlik, Shelton g. Stanfill (Chair), Joseph Steinberg, Linda C.