The United Kingdom's Experience in Revitalizing Inner Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Low Emission Buses – Includes AQ

Lower Carbon and Cleaner Air: Opportunities for Buses Low Emission Bus Workshop Cardiff Principality Stadium, 19th July Connect | Collaborate | Influence Daniel Hayes Project Manager Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership LowCVP: A unique public-private membership organisation, building evidence and creating robust policies and innovation in the UK Government & Public Bodies Environmental & Academia Fuel Suppliers Fleet Technology Operators Suppliers Automotive Manufacturers And Many More… Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership LowCVP Activity & Policy Cycle - Robust Research, Policy and Information The LowCVP exists to Roadmaps and accelerate shift to low research carbon vehicles and fuels and stimulate UK business opportunities Identify Barriers and Market information/ Opportunities dissemination Understand and Investigate Disseminate and Stimulate Accelerate Build Market Understanding Influence Policy Develop technology Implementation Key: LowCVP activity Develop tools/policies Incubate and Influence Member organisations The Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership Current State of Play in Wales In 2016/17… • 1,500 registered PSV buses in Wales (-25% from 2006/7) • 2,100 citizens/bus, GB average is 1,600 citizens/bus • 100 million passenger journeys (-16% from 2006/7) • 32 journeys per head, GB average is 77 journeys per head • 45% of all bus journeys are concessionary fares (34% GB average) • 1 car for every two people in Wales … only NI has more cars/head Plenty of Opportunities for Growth of Bus Market in Wales! Long term transport strategy must include modal shift Bus strategy must include reduction of emissions (CO2, NOx)… The Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership National UK Bus Policy Evolution Development of evidence based bus policy over the last decade to reduce emissions… 2007-08 2009-15 2015-16 2016-2018 £30m Green Bus Defining an Fund £3m SGBF 7 Definition of a Creation of a OLEV Ultra Low Low Carbon LCEB BSOG LCEB Low Emission B.E.A.R. -

Cardiff Auto Receivables Investor Report July 2021

Classification: Public# CARDIFF AUTO RECEIVABLES SECURITISATION 2019-1 plc INVESTOR REPORT JULY 2021 Overview Reporting Date 12 August 2021 Collection Period 22 June 2021 - 21 July 2021 Interest Payment Date 16 August 2021 Deal Overview / Trigger Events Deal Name: Cardiff Auto Receivables Securitisation 2019-1 Issuer: Cardiff Auto Receivables Securitisation 2019-1 plc 1 Bartholomew Lane, London,EC2N 2AX, United Kingdom Contact Details Name Email Address Gavin Parker [email protected] 10 Gresham Street, London, EC2V 7AE Chris Morteo [email protected] 1st Floor Alexander House, Pier Head Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 4PB Jacqui Keith [email protected] 1st Floor Alexander House, Pier Head Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 4PB Stephen Davies [email protected] 1st Floor Alexander House, Pier Head Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 4PB Nelson Lirio [email protected] 1st Floor Alexander House, Pier Head Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 4PB Key Parties/Details Rating (if applicable) Role LEI Number Name Address DBRS / S&P Originator 2138008UXJZAK9L5PE86 Black Horse Limited N/A 25 Gresham Street, London, EC2V 7HN, United Kingdom Issuer 21380029WJFUM99THL82 Cardiff Auto Receivables Securitisation 2019-1 plc N/A 1 Bartholomew Lane, London,EC2N 2AX, United Kingdom Seller 2138008UXJZAK9L5PE86 Black Horse Limited N/A 25 Gresham Street, London, EC2V 7HN, United Kingdom Servicer 2138008UXJZAK9L5PE86 Black Horse Limited N/A 25 Gresham Street, London, EC2V 7HN, United Kingdom Cash Manager 2138008UXJZAK9L5PE86 Black Horse -

Economic Significance of Tourism and of Major Events: Analysis, Context and Policy Calvin Jones ’ UMI Number: U206081

Economic significance of tourism and of major events: analysis, context and policy Calvin Jones ’ UMI Number: U206081 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U206081 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Ca r d if f UNIVFRSITY PR I i YSG OF CA‘ RD W BINDING SERVICES Tel +44 (0)29 2087 4949 Fax +44 (0)29 20371921 e-mail [email protected] Sum m ary The papers presented in this Thesis focus upon the analysis of recreational and sporting activity as economic phenomena. They link the analysis of tourism and sport to wider public policy and economic development debates, applying economic analytical techniques to sport and leisure in a novel manner and charting the development of new tools which enhance our understanding of the economic contribution of these important activities. A number of the papers contained here focus on the extent to which sporting and leisure activity can further regional and national governments' aspirations for economic development, and at what cost. Two of the papers refine economic impact methodologies to better account for the impacts of discrete sporting and cultural events or facilities, using a high level of primary input data, and placing of the results firmly within the local economic development context. -

The Economic Impact of Energy Transition in Wales

The Economic Impact of Energy Transition in Wales A Renewable Energy System Vision for Swansea Bay City Region About the IWA We are the Institute of Welsh Affairs, Wales’ leading think tank. We challenge, inspire and drive change, making Wales a better place to live and work for everyone. We are independent of government and political parties. We bring together experience and expertise from all backgrounds to collaborate on the most important issues facing Wales. We come up with ambitious but practical and informed ideas to improve the economy, education, governance, health and social care and the media. Our vision is to create a Wales where everyone can thrive. For more information about the IWA, its policy work, and how to join, as either an individual or corporate supporter, contact: IWA – Institute of Welsh Affairs, 56 James Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EZ tel: 029 2048 4387 | email: [email protected] | www.iwa.wales Produced for Institute of Welsh Affairs © IWA, September 2018 Design: www.theundercard.co.uk About the author Calvin Jones is a Professor of Economics and Deputy Dean at Cardiff Business School, and a Visiting Professor at Napier University Business School. He holds a PhD in the Economics of Tourism and Major Sports Events. His recent research has focused on energy economics, including the regional economic impact of renewables and of community energy. Calvin Jones, Cardiff Business School Colum Drive, Cardiff CF10 3EU Contact: Professor Calvin Jones [email protected] Tel: 02920 875470 About Re-energising Wales The Institute of Welsh Affairs’ ‘Re-energising Wales’ project is a 3 year project (April 2016-April 2019) that will deliver a plan to enable Wales to meet its projected energy demands entirely from renewable sources by 2035. -

Devolution Decade

spring 2009 Production Editor: John Osmond Devolution Decade Assistant Editor: Nick Morris Associate Editors: On the face of it the verdicts we publish in this issue by leading protagonists in Geraint Talfan Davies, Rhys David the 1997 referendum on the first ten years of the National Assembly make pretty depressing reading. Professor Kevin Morgan, who chaired the Yes Campaign, is Administration: Helen Sims-Coomber, Clare Johnson especially damning. He lets us in to what he describes as “devolution’s dirty little secret”, its failure to make a fist of developing the Welsh economy. And the Design: statistics are incontrovertible. In terms of our prosperity relative to most other www.theundercard.co.uk parts of the United Kingdom, we’ve actually gone backwards in the first decade To advertise – declining from 77 to 75 per cent of the UK’s average GVA. When we started Tel: 029 2066 6606 out the Assembly Government’s stated ambition was to climb to 90 per cent by Institute of Welsh Affairs 2010, an aspiration that has been quietly dropped. One way or another our other 4 Cathedral Road contributors all point to the economy as the central reason for their Cardiff CF11 9LJ disappointment with devolution’s record so far. Tel: 029 2066 0820 Yet a narrow focus on the economy, important as it undoubtedly is, leads Email: [email protected] to a zero sum game. Devolution is about much more than that. And anyway, www.iwa.org.uk as Kevin Morgan himself concedes, the amount that government can do to The IWA is a non-aligned independent think- influence the economy will always be limited, especially a government with so tank and research institute, based in Cardiff with relatively little control over the main economic levers as the one in Cardiff Bay. -

Individual Responsibility of Ministers: an Outline of the Issues

The Individual Responsibility of Ministers: An Outline of the Issues Research Paper 96/27 21 February 1996 The individual responsibility of ministers is a vital aspect of accountable and democratic Parliamentary government, yet it is a 'convention' which is difficult to define with certainty and which, to a large degree, depends on the circumstances of each individual case. This Paper seeks to explore, in general terms, the subject as a whole and several interesting examples from the era of Crichel Down in 1954 onwards to illustrate the issue. It does not seek to provide a comprehensive analysis of ministerial responsibility (including collective responsibility) or Parliamentary accountability. Barry K Winetrobe Janet Seaton Home Affairs Section Reference and Reader Services Section House of Commons Library Summary Individual ministerial responsibility is an important if complex constitutional issue. It is often described as a constitutional convention, and this Paper examines its nature in that context, and in relation to collective responsibility and in the light of developments such as the growth of select committees, the development of Next Steps agencies and quangos, and the publication in 1992 of Questions of procedure for Ministers. The nature of individual responsibility in action is described briefly, including aspects short of a ministerial resignation or dismissal. The interesting, if short, debate on ministerial responsibility on 12 February 1996 is considered. A number of modern examples of situations where individual responsibility could be said to have arisen are examined, purely to illustrate various aspects of the 'convention'. It is not intended to be a comprehensive list. It covers significant episodes such as Crichel Down in 1954 (in which Sir David Maxwell Fyfe set out what is often regarded as the classic statement of the traditional doctrine), the Falklands (1982) and Westland (1986), and includes instances where resignation demands were successfully restricted such as Court Line (1975) and the Maze Prison escape (1983). -

Cardiff Meetings & Conferences Guide

CARDIFF MEETINGS & CONFERENCES GUIDE www.meetincardiff.com WELCOME TO CARDIFF CONTENTS AN ATTRACTIVE CITY, A GREAT VENUE 02 Welcome to Cardiff That’s Cardiff – a city on the move We’ll help you find the right venue and 04 Essential Cardiff and rapidly becoming one of the UK’s we’ll take the hassle out of booking 08 Cardiff - a Top Convention City top destinations for conventions, hotels – all free of charge. All you need Meet in Cardiff conferences, business meetings. The to do is call or email us and one of our 11 city’s success has been recognised by conference organisers will get things 14 Make Your Event Different the British Meetings and Events Industry moving for you. Meanwhile, this guide 16 The Cardiff Collection survey, which shows that Cardiff is will give you a flavour of what’s on offer now the seventh most popular UK in Cardiff, the capital of Wales. 18 Cardiff’s Capital Appeal conference destination. 20 Small, Regular or Large 22 Why Choose Cardiff? 31 Incentives Galore 32 #MCCR 38 Programme Ideas 40 Tourist Information Centre 41 Ideas & Suggestions 43 Cardiff’s A to Z & Cardiff’s Top 10 CF10 T H E S L E A CARDIFF S I S T E N 2018 N E T S 2019 I A S DD E L CAERDY S CARDIFF CAERDYDD | meetincardiff.com | #MeetinCardiff E 4 H ROAD T 4UW RAIL ESSENTIAL INFORMATION AIR CARDIFF – THE CAPITAL OF WALES Aberdeen Location: Currency: E N T S S I E A South East Wales British Pound Sterling L WELCOME! A90 E S CROESO! Population: Phone Code: H 18 348,500 Country code 44, T CR M90 Area code: 029 20 EDINBURGH DF D GLASGOW M8 C D Language: Time Zone: A Y A68 R D M74 A7 English and Welsh Greenwich Mean Time D R I E Newcastle F F • C A (GMT + 1 in summertime) CONTACT US A69 BELFAST Contact: Twinned with: Meet in Cardiff team M6 Nantes – France, Stuttgart – Germany, Xiamen – A1 China, Hordaland – Norway, Lugansk – Ukraine Address: Isle of Man M62 Meet in Cardiff M62 Distance from London: DUBLIN The Courtyard – CY6 LIVERPOOL Approximately 2 hours by road or train. -

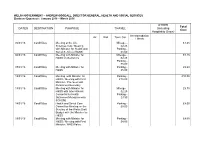

DATES DESTINATION PURPOSE TRAVEL OTHER (Including

WELSH GOVERNMENT – ANDREW GOODALL, DIRECTOR GENERAL, HEALTH AND SOCIAL SERVICES Business Expenses: January 2016 – March 2016 OTHER Total DATES DESTINATION PURPOSE TRAVEL (Including Cost Hospitality Given) Accommodation Air Rail Taxi / Car / Meals 05/01/16 Cardiff Bay Meeting at the Life Mileage - £7.25 Sciences Hub / Meeting £2.25 with Minister for Health and Parking - Social Services (H&SS) £5.00 06/01/16 Cardiff Bay Meeting with Minister for Mileage - £7.25 H&SS on Genomics £2.25 Parking - £5.00 07/01/16 Cardiff Bay Meeting with Minister for Parking - £5.00 H&SS £5.00 12/01/16 Cardiff Bay Meeting with Minister for Parking - £10.00 H&SS / Meeting with First £10.00 Minister / Pre-meet with Permanent Secretary 13/01/16 Cardiff Bay Meeting with Minister for Mileage - £5.75 H&SS with International £2.25 Consortia for Health Parking - Outcomes Measurements £3.50 (ICHOM) 14/01/16 Cardiff Bay Health and Social Care Parking - £8.00 Committee Meeting on the £8.00 Scrutiny of the Wales Draft Budget with the Minister for H&SS 19/01/16 Cardiff Bay Meeting with Minister for Parking - £4.00 H&SS / Meeting with First £4.00 Minister / NHS Wales Executive Board and Joint Overview Meeting 20/01/16 Cardiff Bay / Bilateral with Minister for Mileage - £11.10 Cathedral Road H&SS and Finance Minister £3.60 / Chairs Development Parking - Session at the NHS £7.50 Confederation Offices 22/01/16 Swansea Permanent Secretary’s Mileage - £22.05 Event at Swansea offices £22.05 25/01016 Cardiff Bay Meeting with Minister for Mileage - £5.75 H&SS on OAQ Preparation £2.25 -

Eulogy for Sir Peter Gregson

SIR PETER GREGSON Address by Sir Michael Scholar in Beckenham Parish Church 6 January 2016 Peter Gregson and I became friends through working together in number 10 Downing Street, then, later, when I took over from him as Permanent Secretary of the Department of Trade and Industry. After his retirement we maintained our friendship and I was honoured to be asked by him several weeks before his death to be a speaker at this service. Peter Gregson was born on 28 June 1936 in the Yorkshire village of Haworth where his father taught in the local school. The family later moved to Nottingham and Peter won scholarships successively to Nottingham High School and to Balliol College, Oxford. Peter was rightly proud of his considerable successes both at school and university. He was Vice Captain of his school, and at Oxford was a top scholar in classical studies, outshining his contemporaries, one of whom was later awarded the Order of Merit for his work in classical philology. Peter was also invited by successive Presidents of the Oxford Union to be a main speaker in a debate every term – although he never competed for elective office in the Union, nor joined any of the party political clubs. That was Peter's way, and set a pattern he was to follow later on. Peter told me that he might have been tempted by an academic career, but that that his tutor wisely - Peter's own word - advised him to do so only if there was nothing else he was capable of. He then took the competitive examination for the civil service, and joined the Home Civil Service in 1961. -

Enoch Powell and the Sovereignty of Parliament Transcript

Enoch Powell and the Sovereignty of Parliament Transcript Date: Tuesday, 12 March 2013 - 6:00PM Location: Museum of London 12 March 2013 Enoch Powell and the Sovereignty of Parliament Vernon Bogdanor Ladies and gentlemen, thank you for braving the bad weather to come to this lecture, which is the fourth in a series on post-War politicians who have “made the weather”, that is, set the political agenda, even though none of them became Prime Minister. The first three lectures were on: Aneurin Bevan, who was founder of the National Health Service; Iain Macleod, the apostle of rapid decolonisation in Africa; and Roy Jenkins, the pioneer of liberal legislation on personal liberties and race relations in the 1960s, and the apostle also of party realignment. Today’s lecture, the fourth, is on Enoch Powell, and he pronounced his surname, incidentally, “Pow-ell” and not “Pole” as people sometimes do. Enoch Powell was a very popular politician and there is a possibility that if we had had a presidential system of direct election, that he might have become leader of the country, though I think the probability is not, but there is a possibility he would have been. But, unlike the first three people I have talked about, Bevan, Macleod and Jenkins, he had no major legislative achievements to his credit, and part of the reason for that, he was in Government only for a very short time, a much shorter time than perhaps most people imagine. He was a member of the Cabinet for just fifteen months, and he held junior posts in Government for a further four years, so he was not a man of Government or of any legislative achievement. -

Impacts of Tourism

Impacts of Tourism Impacts of tourism Over the last twenty years there has been a growing awareness of the impact tourism has on the environment and societies in which tourism takes place. As mass tourism first developed along the Spanish coast and other areas, there was little concern for the negative impacts that tourism was having on the environment of the area or on the lives of the people living in the area. In recent years, concepts such as eco-tourism, responsible tourism and sustainable tourism have emerged. This is as a result of more research being undertaken into the range of impacts tourism creates and the ways in which these impacts can be managed more carefully. It is usual to classify the positive and negative impacts of tourism under the following headings: • economic impacts • environmental impacts • social impacts • cultural impacts Economic Impacts Positive Tourism generates income for a variety of businesses and creates a wide range of employment opportunities. At the global scale, tourism is seen as one of the world’s largest and fastest growing industries. This trend has continued throughout the last 50 years. Within the United Kingdom, it is estimated that inbound tourism generates about £19 billion each year. Domestic tourism, including day trips and staying visits, generates over £60 billion per year. In terms of employment, it is estimated that in the United Kingdom 1.4 million jobs are directly related to tourism. As well as generating employment and income, another positive impact of tourism is improvements in infrastructure. These include road and rail improvements, airport development and improvements in utilities, such as water supply and telecommunications. -

Thriving & Prosperous Economy Programme

Programme Intelligence Report Thriving & Prosperous Economy (Updated 9th August 2016) Workstream: Sustainable Employment When compared with the other core cities, it can be seen that only Manchester (9.2%) saw a larger expansion in active Promote entrepreneurship and innovation enterprises over the year. Gross Value Added (GVA) for Cardiff and the Vale of Births, Deaths & Active Enterprises in Cardiff, 2004-14 Glamorgan in 2014 was £10,655m, representing 19.6% of the 11,900 2,000 Wales total, while GVA per head (£22,107) exceeded the 1,800 comparable figure for Wales (£17,573) but was below that of the UK (£24,616). 1 11,400 1,600 1,400 For 2015 the median gross weekly full-time earnings of those 10,900 1,200 working in the local authority is £499.20; down 1.0% on the 1,000 2 previous year . This is greater than the Welsh average 10,400 800 (£473.40) but is just 94.6% of the UK figure (£527.70). The 600 No. Births/Deaths equivalent pay for full-time workers residing in Cardiff No. Active Enterprises 9,900 400 (£510.20) also exceeds the comparable figure for Wales 200 (£484.40) but is only 96.7% of the UK median, although it has 9,400 0 increased by 2.8% over the year. There were 11,515 active enterprises in Cardiff in 2014; the largest figure since records began in 2004. This represented Active Enterprises Births Deaths an increase of 6.6% over the year, which was also the Source: Business Demography, ONS greatest annual growth rate in Cardiff over the period, and 3 compared to a 3.0% rise across the whole of Wales .